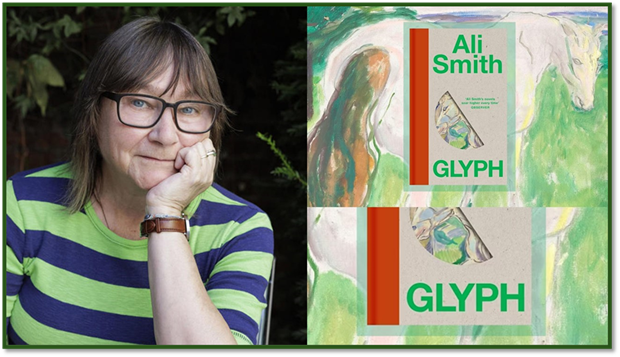

There has never been a greater need to critique the assumption that ‘our world has changed’, than when it is used ‘to justify massive expenditure on the weapons industry again to keep us safe in the new era, the doorway, or threshold, of which is already blocked up with the brand new dead’.[1] It’s always on our ‘to-do list’ but ‘never gets done’. This is a blog on the urgent new novel by Ali Smith (2026) Glyph, London, Hamish Hamilton.

There is no other writer of our age more important to that age as it develops and malforms before our eyes beyond anything resembling the dignity once accorded to our empathies with life (human, animal or vegetable), the openness of the senses to the dangers of being shut up and losing our openness to criticism of how those in power say the world needs to be in the future. We ought to have seen the futures we fear in the past before they too became the past or our present. That is the fundamental relationship between Glyph and the novel it follows but which precedes it in imagined time, Glyph. As well as responding obliquely to our prompt question, this blog contains some thoughts on the wonderful thing that is Ali Smith’s newest novel, where even its characters have read her last novel Gliff, that is this novel’s companion: Ali Smith (2026) Glyph.

Novels, of course, often contain readers (Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey and Emma Bovary in Madame Bovary for instance), whose reading matter fails to define seriously enough their response to the worlds in which they are made by their omniscient authors to live. This novel entitled Glyph, however, has readers that have both read the companion to that novel in which they appear, the novel entitled Gliff (for my blog on that novel use this link). The critics don’t feel the significance of this quite, as I do. Kieran Goddard, of which much more later, doesn’t mention the fact, even though he cites some words said in Glyph about Gliff (see below). In The Guardian he gives a refreshingly warm welcome however for the political drift of Glyph, saying:

Never knowingly unknowing, Ali Smith pre-empts the most likely criticism of her latest novel, Glyph, when a character says: “I’m just not sure that books that are novels and fiction and so on should be so close to real life … or so politically blatant.” [2]

Sarah Moss, in The Observer, however, both notes the fact and notes further the similarities and differences of structure and narrative types.[3] The fullest account of this trait in the novel is by Anna Walker of The Conversation, who analyses what she calls ‘a further dimension’ to the novel read as a ‘standalone’. Again some parallels are noted, and one ‘complication of the meaning of some of the links between the two novels’ (read her on this) but two other points she makes interest me more. First she notes that Smith wished to use her second novel to offer ‘a humorous reflection of real-world reader responses to Gliff: “A bit too dark for me. A bit too clever-clever, a bit too on the nose politically for a novel.”

Second, she sees the relationship between the novels, and the ‘playful twistiness’ this involves to focus ‘a passionate commitment to a more just society’.[4] The best readings of the ‘art’ of Ali Smith currently would probably be based on a combination of both Moss’s and Walker’s views, but they lack political punch in my view for the searingly political novel I read. Walker emphasises the play in the novel, Moss even feel uncomfortable about Smith’s world view as containing, as she says, ‘nonetheless’ (as if this was a kind of embarrassment for a literary writer with a refined sense of humour):

reason to find in Smith’s writing a (not unjustifiable) deep and deeply puritan distrust of pleasure as we live through the worst kind of interesting times.

No such pussyfooting around Smith’s political challenge to us can be found in Goddard. I love Goddard’s statements on this novel’s politics, particularly its unequivocal and ‘explicit engagement with the Israeli government’s apartheid and genocide in Palestine’ and ‘with one of the “longest and deadliest military occupations in modern history”.[5] His review even perhaps diagnoses the reason for the air of embarrassment with Smith in Moss and Walker, but particularly Moss. He says forthrightly of Smith’s refusal to turn away from the fact of the Gaza genocide, and instead describe it through the eyes of someone reluctant to watch it (more on this later):

It is a bold move to be so morally unflinching, especially in the face of a perceived aesthetic orthodoxy that so often privileges distance and irony, but in Glyph we see a major British writer answering the call of the day when so many others have equivocated or turned away. There is also something about Smith’s relentless focus on language that makes her particularly well suited to the task. As Orwell reminded us: “political language … is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind”. Smith’s sensibility is fine-tuned to grapple with the avalanche of passive-voice headlines, asymmetric categorisations, outright linguistic inversions and semantic absurdities that have accompanied the increasingly desperate attempts to justify the unjustifiable.

I quote that at length because it is rare to see the literary criticism of ‘literary’ fiction so self-critique its, and its culture’;s, presumptions of what constitutes the ‘literary’. The Smith novel deals only with those who ‘equivocate and turn away’, not so much with another class of present day writers who have directly colluded with the cover-up of genocide (see my blog on Peter Oborne’s Complicit at this link).

The most obvious opening reference to that fact that Smith wants in Glyph to look at the embarrassment involved for some critics in reviewing Gliff comes in the novel when Patricia (named Patch as a child) is visiting her elder sister, Petra, in London, with her teenage foster-child (‘possible’ child for adoption in the child’s terminology), Bill. Bill attends though not at Patricia’s full invitation for Bill has just been picked up by her at a police station by Patricia because she has been arrested for waving a scarf that could be interpreted as being in support of a ‘newly proscribed organisation’. Bill was neither waving the scarf, nor did it relate to the group Palestine Action, but it is a clear precursor for the proscribed activities in Gliff. After an evening in which Bill becomes angry at what she sees as the political quiescence of her adult companions (possible mother and possible-aunt) who seem to care more about the uncertainties of the historical past than the current atrocities in Gaza, Bill sleeps in the sitting-room on a couch.

In the morning Patricia comes into the room to find Petra and Sam in reconciliatory conversation, amongst which is this moment, where Bill espies a rather heavily damaged book:

She sees a book open with its pages flat to the floor under the armchair on the other side of the room.

I’ve read that book, she says. The book about the kids with the horse.

Oh yeah, Petra says. Patch sent it to me.

She fishes it out from under the chair. She tries to close it but it’s a paperback and the fact that it’s been lying open on the floor makes it hard to close it without it springing back open by itself so she puts it down closed on the table and puts an empty coffee pot on top of it to keep it shut.

I found it a little blatant, Petra says. I was left quite uneasy by it.[6]

Despite the fact that her younger sister sent her the book, presumably because it reminded her, as it must us, of stories of children moved by the story of a horse facing human inhumanity and the fact that both sisters in the childhood in the 1990s had listened to the story of a man who, at his own risk, cared more about a horse than preserving his own life and was shot as a deserter for leading the horse out of danger.

At that earlier time Petra had eased the emotions of Patch about this story and another, that of a man flattened by a convoy of heavy tanks into a literally ‘flat’ character, by inventing stories that she claimed came from the dead flattened man, whom Patch had called Glyph when hallucinating his ‘ghost’. Petra as an adult has lost her job amending the parts of Artificial Intelligence (AI) operations that sounded not human enough, because AI now sounds more human than humans themselves, and she now returns to those childhood stories more disturbed than the younger sister she comforted then. She sees, feels and senses too proximately the ‘blind horse’ in the childhood story.

Bill shocks Petra by suggesting that the blind horse she sees, hears and feels wrecking her bedroom may be some kind of suggestion created by reading Gliff. Petra feels suspicious of Gliff and says she finds the book by Ali Smith ‘blatant’, by which she seems, from other words she uses, that it is too politically critical of the status quo as the model of its dystopia of the future, and for some reason, that may be its politics or not, leaves her feeling ‘quite uneasy’. Petra has grown into a woman no longer able to rest on her control of the emotions of others or herself by telling stories, becoming someone who is instead perhaps controlled by them.

And therein likes an issue about the power of stories in this book and the means readers, hearers or viewers of them find to protect themselves, or welcome, those stories. For, I will argue, if Glyph is a means of understanding the future dystopia of Gliff, it is because of the resistance to the power of stories to excite the negative truths of human behaviour that have made their target of destruction the green environment, animals, and other humans, now treated as they already treat animals. Stories could, were writers thus willing require readers to care in a manner that actively resists those tendencies in politics. The best defence of our time is not to see, hear or even smell it happening at all, the other is to decide that is a politically-motivated misrepresentation, a blatant call on our feelings and action that makes life hard for us, and it is this view of present politics that characterises both Petra (hard as the stone she is named in Greek after) and Patch, who thinks all might be quickly repaired with patches of soft fabric.

The character Petra found Gliff ‘blatant’ but much of the metaphoric play around the novel involves the ambiguities about its joint discovery by Bill and Petra. Presumably thrown from the shelves in her bedroom by the ‘perhaps’ hallucinated ‘blind horse’, it is has ended up upside down flattened open on the floor, but not readable thus – however ‘open’ for reading. Bill finds a way to weight the book ‘shut’, defying its capability now, thus wrecked of ‘springing back open by itself’. The book is not only shut but ‘shut up’. And this makes it cognate with other symbolic tale tellers reduced to silence, oft by violence, in stories in Glyph; stories wherein:

All hell breaks loose. Plot goes mad. Atrocity follows atrocity. Everybody is full of murderousness. Blood everywhere.

Stories not unlike those in Palestine in our present time, which journalists are forbidden to see, hear or report without accusation of lying. Yet this late story in the book is one ‘we’ve been telling ourselves for over two millennia’: the rape of Philomel or Philomena by King Tereus and her transformation after her tongue is torn out (to stop her telling of her oppression) into a nightingale. But this is no hopeless story where only the powerful have resources, even without her tongue the imprisoned sex slave Philomel refuses to be totally silenced:’ Locked behind those high walls she works at getting proficient at telling people things by being silent’.[7] Such stories always were political, and Smith knows they have, unfortunately analogues in the history of current political wars. For instance, Smith earlier tells the story of Ukrainian journalist, Viktoria Roschyna, without naming her, though she leaves us to draw the parallel with Philomena. Her interpretation of the removal of her body parts Smith reads as about the symbolic silencing of a woman’s politically aware voice, and perceptual sense organs, though other say the reason was to disguise the torture endured by Viktoria at the hands of Russian captors.

… specifically because she’d been a journalist, they did some things to her body that Bill is hoping to God they did after she died and not before. They removed everything in her body that had made her a journalist: her eyes, her tongue, her brain, her vocal cords.

This is true.

This happened to a real person.

This is not just some random made up ghost story from the past.[8]

This section of memory serves two purposes. It places Bill’s political consciousness in contrast with the haunting and haunted neuroses about the uncertainly factual dead (and hence ‘ghosts’ like others in the book) of the past of Petra and Patch Wild. It also focuses the network of references to people being robbed of their ability to witness atrocity in their own world (eyes, brain) and telling of those atrocities (brain, tongue, and vocal chords). The fascinated descriptions of vocal chords that follow, as of ears in the case of Patch, highlight the physical and visceral body – the animal human body – as functional in moral reportage. Likewise of course the blinding of a horse that make neither a ‘nod’ or a ‘wink’ (the names of the first two sections of the novel with various exempla within each) visible to ‘blind horse’ (the third section) – possibly because of their subtlety of hint – being closed rather than open codes, known only to the cultural members to which they have meaning).

In truth however the desensitisations that led to the kind of future society of Gliff are really those which cause contemporaries effectively not to see, not to hear nor even smell the presence of dehumanised behaviour passing as its opposite or as justified in some other way, such as in the capacity of our present society to accept that we are too busy to notice evil in operation, or at least act upon it – even in reporting it to others. In such cases our eyes, hears, noses and voices are removed metaphorically. There is an early instance in the novel, where Petra is pursuing her education in the Italian language at the same time as having various digital screens available to her such that, as she labours at her Duolingo class, playing out its gaming methods, she sees a news channel, enough to persuade herself that she is attending to it but not enough to get engaged with what it tells her about her contemporary world, as she watches a child pulled from the rubble of a bombsite – whether in Kiev or Gaza we do not know, though the hopelessness and ubiquity of rubble that once were homes and hospitals suggests Gaza.

I can’t turn the TV news screen off. That would be an admittance not just of my hopelessness and helplessness but of my callousness. I leave it on because like everybody else now I’m a person who can cope with several screens. So I’m sitting simultaneously clicking things on another screen which is sending sentence after sentence for me to translate ….

Compounding her very ‘admittance not just of my hopelessness and helplessness but of my callousness’ is that her memories turn to past wars, wars in which she could not intervene or register in protest, only ‘observe’ in her memories – the stories which are the substance of those negotiated between the Wild children come from this domain (the First and Second World Wars in Europe) – is that the Italian she learns is advertised as ‘future tenses of verbs: ‘ Talk about the future is what it says at the top of the Duolingo unit I’m now on’. Yet that is an oversimplification, Petra realises as she avoids more pictures of war live-screened:

Actually this unit I’m on is titled wrongly. We’re not just talking about the future here but about how to conjugate what I think used to be called – maybe still is called – future in the past:

You can see it will not have been understood.

It will have been used for something else.

… [9]

Those examples of ‘future-in-present’ tense are, as always in Ali Smith, of wide and spreading reference, both of the two first ones I quote above could have been used of her novel, Gliff, wherein which usage the publication of Glyph represents the future that proves her first novel would not be ‘understood’ before the second was completed and has not been, even by characters in that novel. But more importantly, the urgency of Gliff as a political statement has been missed, wherein not only atrocities in the Ukraine and Gaza are in part a product of our refusal to understand the hold that might-is-right arguments in the world were taking place under our passive refusal to believe that truth and, of misled response to them – to collude with a future whose watchwords are increased border defensive security and rearmament.

In fact many political issues are compounded in our lack of understanding even in future-past comparisons about past atrocities. Take the wild girls reception of the story of the flattened man crushed by a convoy of tanks, and the guilt of the narrator of that story who did not bury that malformed body with dignity. Petra and Patch’s thoughts circle on how ‘matter’ abandoned on a road (what that body has become in one perspective) could have been disposed in the early twentieth century, where even the practical civic politics of ‘waste’ disposal is implicated:

Also I don’t know if they even had things like litter bins and landfill back then, I said. I’ve never noticed any of those things in any old films from then or read about them in books about then or anything. If they didn’t have landfill, she said, where did they put their rubbish?

I think they had a lot less stuff to throw away in those days, I said.

Anyway. What was left of whoever got flattened would’ve broken down naturally, being organic matter. Like the skin off an apple.

Organic matter, she said. Like an apple. Then she looked down at her own arms. She took one of her feet in her hands and sat looking at her toes.

Matter doesn’t matter, she said.

I saw she was about to cry again and that I’d have to be quick.[10]

He characterisation in dialogue of the two girls is precise. Patch is soulfully sensitive, or sentimental, depending on the frame of interpretation. Her ruminations have to be stopped by distraction, Petra thinks, and here is born her bogus contact with the ghost of the flattened but raised mark on the road, the girls name Glyph. Petra herself easily distracts herself from the human content of the story into thoughts of modern against older waste disposal logistics, and the transformation in her language of a body into ‘stuff to throw away’ or organic matter’. To Patch the move from flesh, once rounded out by a person, into matter is a sad thing in itself. Her reading of Petra’s distracted thought, washing away the impact of a tragic story, is precise: “Matter doesn’t matter, she said”.

Other stories look for words to show whether living animals, including humans, are mere matter, indistinguishable from the rubble of Kiev or Gaza from which, if ‘lucky’ (a questionable term in these circumstances), they emerge) or whether we need another form of language, however old-fashioned, like ‘soul’, which is invoked when the novel discusses AI. Much of the novel tells stories – of the blindness to the march of AI to replace human responses, in mimic at least, the armament of borders and their imperialist extension (back to Russia and Israel)to the rubble of Gaza where a horse emerges therein in a message Bill receives from a young friend:

It is film footage 1 min 43 seconds long from one of the wars happening now, probably Gaza because of the backdrop of miles of grey ruin behind it.

The film is of a pile of bricks and stones.

Nothing happens.

Then the broken bricks and chunks of building start to move and heave, back and fore, like they’re breathing. A horse’s head, the bridge of the nose first, pushes through and out of the pile of stuff and thrashes around. It is a horsehead made of dust. Dust and rubbly shapes shake loose down from the ears and off the neck. Front legs are suddenly there and scrabbling, and a broad chest appears, back legs appear, kicking and finding their footing, then the whole brickheap rises like it’s getting to its feet itself, as the horse does, as the horse sheds the broken stuff.

Then a horse the colour of stonedust and concrete stands in a spill of broken stones and concrete, dust rising off it like smoke. It shakes itself out of there and stumbles over the stones and away.[11]

Herein ‘matter, or ‘rubble’, or ‘stuff’ comes to life as a horse, and unites from Gaza (an ‘it’ becoming alive with something that has haecceity, in the language of the medieval scholastics – something that communes with the shot deserter’s care of a gas-blinded warhorse, the pit ponies he cared for before the war, the dreamt version of him in Petra’s bedroom reminding her of responsibilities misunderstood, and the horse escaping slaughter in Gliff, that may have triggered Petra’s sense hallucinations of horsiness, even the smell of ‘horseshit’ noticed by Bill.

From out of wars come stories we dispose of in other consolatory stories at our peril. We have no right or entitlement to being comforted without swallowing first our responsibilities – why Sarah Moss finds Smith a little ‘puritanical’ on play and pleasure. I can’t improve on Kieran Goddard’s comment:

…, two of the central images of the novel draw their potency directly from the everyday horror of expansionist slaughter. The two sisters hear a story from the second world war, about a young soldier flattened by a tank whose body is left to rot in the road. Later they begin to half-seriously communicate with his ghost, calling him Glyph. On the one hand, Smith is playing with the question of what makes a character “flat” versus what makes one three-dimensional. On the other, especially when many readers will have images and reports of similar deaths in Palestine so firmly in mind, Smith is raising ethically substantive questions about representations of the dead, about who gets to speak and who is decisively silenced. When Patch’s teenage daughter watches a distressing video of a horse trapped under tons of rubble, she notes that it was “probably Gaza”; as readers, we are left in little doubt.

Even Smith’s response to the weaponisation of Forster’s Aspects of the Novel, on characters flat and ‘rounded’, against Smith, a common occurrence, becomes part of the tongue-in-cheek fightback from this most major novelist, challenging the aesthetics of contemporary fiction that puts matters of literary criticism above content response, rather than on a par with such response, is politically edged. The issue is whether we Choose to be robbed of the ability to perceive the evils in the world before us, robbed of eyes, brain and ears drowned by tinnitus, and our ability to use tongue and vocal chords to speak up against them. otherwise why write Gliff, let alone Glyph. Every sentence of this novel however is aesthetically brilliant – every sentence calls forth comment on its mastery-mystery. So I ought to stop there.

Bye for now

With great love, especially to Joanne, who is reading the novel now. Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Ali Smith (2026: 18) Glyph, London, Hamish Hamilton

[2] Keiran Goddard (2026) ‘Glyph by Ali Smith review – bearing witness to the war in Gaza’ in The Guardian (online) available at:https://www.theguardian.com/books/2026/jan/27/glyph-by-ali-smith-review-bearing-witness-to-the-war-in-gaza

[3] Sarah Moss (2026) ‘Ali Smith’s Glyph goes back to the future’ in The Observer (online) [Thursday, 29 January 2026] Available at: https://observer.co.uk/culture/books/article/ali-smiths-glyph-goes-back-to-the-future

[4] Anna Walker (2026) ‘Ali Smith’s Glyph is an exhilarating and excoriating follow-up to Gliff’ In The Conversation (online) Published: January 28, 2026 4.32pm GMT Available at: https://theconversation.com/ali-smiths-glyph-is-an-exhilarating-and-excoriating-follow-up-to-gliff-274075

[5] Keiran Goddard op.cit.

[6] Ali Smith (2026: 216) Glyph London, Hamish Hamilton.

[7] Ali Smith 2026 op.cit: 257f.

[8] Ibid: 238c.

[9] Ibid: 14- 17.

[10] Ibid: 32f. c.

[11] Ibid: 228c.