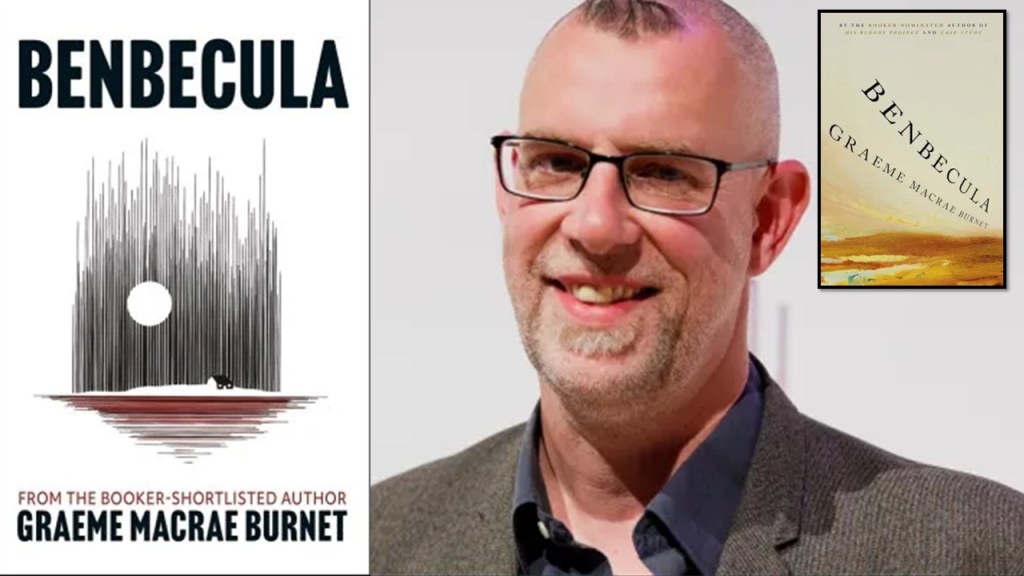

Losing interest in ‘the double’ in the interests of the polymorphous. Do some themes in psycho-pathological fiction get overworked: Using as a test case Graeme Macrae Burnet’s 2025 novel Benbecula, Edinburgh, Polygon.

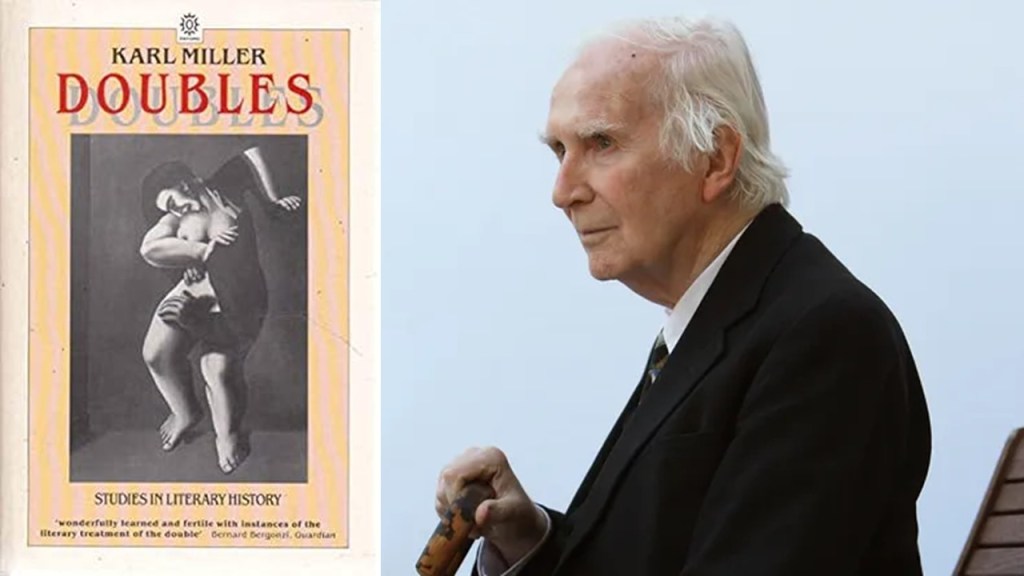

I used to be fascinated by duality – that a thing we thought of as one thing was, in fact, two things: even more so when the things they were could be described by binaries – antonyms like good and evil, open and closed. Perhaps this came from influences – for I was taught by Karl Miller (when he replaced Frank Kermode at UCL), at the time he was writing his best book Doubles, and gave a seminar on both (in a Romantics module) James Hogg’s The Confessions of A justified Sinner, and (on a ‘Victorians’ course) Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. That both were classic Scottish novels matters for the psycho-pathological theme of the double, though always there blatant in English literature, was the more explored in Scotland, with its greater links to the European Continental mainland, in cosy war with the Catholicism of that Continent and its militant form of hegemonic Protestantism, like unto that of German and Swiss moralistic rebels against the Church.

Karl Miller’s specialty in ‘the double’ (at least in the UCL seminars) was the manner in which duality stories explored masculinity, especially through the cognate theme of fathers, sons or their substitutive dynamics, although his book stresses that his interest in the ‘double or dual self’ ‘is literary, rather than psychological or philosophical’, although when defined all those domains seem present in the literary anyway. – even Miller has to use the word ‘supervention‘ below, rarely used except in metaphysics or in arenas where the metaphysical has to be invoked, as in most depth psychological paradigms like psychodynamics. Based on ‘ancient superstition’ the Doppelgänger was used, he says, ‘to generate, in popular and para-medical contexts, the hypothesis of a supervention, within the individual, of autonomous and adversary selves, and to transform the understanding and practice of literature’. [1] But not just literature clearly, given such a sweeping basis in the understanding of the ‘self’ as a non-unitary domain in which being gave way to at least two distinct beings.

I was drawn to Graemse Macrae Burnet partly through my continuing fascination with areas of literature and Scottishness that Karl Miller opened up, although Burnet’s pedigree was more to my taste ultimately – working class Glasgow rather than entitled enlightened patrician Edinburgh. However, I read Burnet’s most recent novel yesterday, and find myself wearying even of his uses of ‘doubles’ to explore darker corners of Scottish lower-class history and literary-psycho-pathological tropes (madness, suicide and murder – especially sexual murder by men). His first novel, His Bloody Project struck me first as a notable fiction when i started blogging (see that first blog here) and when thinking about Booker nominees later (see this blog reissued for that reason but virtually the same as the last version – so why reissue?) and Burnet’s finest novel of psycho-pathology of the double, Case Study (see the blog here). Case Study remains his best novel. This is partly because Benbecula retreads tow much of the ground of the former novels.

Benbecula is one of the Darkland Tales eries from Polygon, of which only one has I think broken moulds in the genre of Scottish criminal murder stories from researched written history – that one being Hex (see my blog on it here) by the incomparable Jenni Fagan. Hex works because Fagan allows her own literary imagination – the same that fires her other best work – to recreate the history of Stuart Scotland whilst Burnet uses his literary imagination largely to infuse into the stories the imaginative and thrilling tropes that make his writing excellent, but to fail to truly take over the ‘history’ he relates. The book keeps coming back to what happened actually on the island of Benbecula in July 1857 when Angus McPhee murdered his parents (use the link to see some of paltry facts of the case), and not through Angus consciousness but that of his brother Malcolm – an illiterate Gaelic speaker in fact – whom is the one reconfigured for this novel and given Burnet traits – an obsession that he is the ‘double’ of brother Angus, and like Robby Macrae, in His Bloody Project, much of that double self might be explained by a shared projection of all of Robby Macrae, Angus and Malcolm McPhee into a self sometimes no different from the willful desires of their rebellious sexual members. Doubles and the phallic other are oft as one. Malcolm says of Angus’s development as a man:

Certain traits that may be excused in a child are less easily forgiven in a man. From the moment he grew hair on his balls Angus had a shameless fascination for those parts of his body and their functions that decency normally dictates are kept private. [2]

We will see Angus attending to those private parts (he obviously masturbates into his own hand as often as Angus), in our mind’s eye, throughout the novel.[3] His sexual projections are not as intrinsically related to the murders in the novel as in His Bloody Project, however. But we will also see Malcolm as equally fascinated by his phallic prize, which one female admirer says might take her ‘eye out”, presumably, we might guess because of its real or imagined size – the lady in question, Mrs MacLeod but formerly his aimed for Peggy MacRury, pretends not to see Malcolm undressing as she prepares his two monthly bath, but Malcolm suspects she sees him from the angle of her stance in holding her back to him. And then Malcolm frequently sees himself and Angus as one and the same being whilst being distinctly two in the apparent flesh. Malcolm says that ‘I was haunted by the sense tha I was not his opposite but his mirror image’.[3] We will see formulations of the mysterious ‘hypothesis of a supervention, within the individual, of autonomous and adversary selves’, with regard to Malcolm throughout not only with regard to Angus but to hints, spoken only to be denied – but why then speak them, of an incestuous desire for his sister, Marion and perhaps responsibility for her murder when she rejects him (all this is obscure in the novel’s mysteries and in Malcolm’s claimed disinterest in ought but sexual auto-stimulation).

The main difference he wishes to see and demonstrate between himself and Angus is the perception, at the least, that he can restrain and contain physical desire and bodily release, even if they are totally the same as those of the diminutive Angus. When considering why he should ‘restrain’ desires, since he does not believe in damnation, he says that ‘what checks me is that I do not wish to be like my brother. Angus was a creature incapable of restraint’.

Everything spilled out of him, whether the curses from his mouth, the farts from his arse or the ejaculate from his cock. He was no better than an animal and it is a commonly held view that I am no better. [5]

In this novel, the events are largely those in the historical record, the additions being a deeper psycho-pathological inquiry into what drives Malcolm, and hints that the answer to the question will tell us something about the constitution of masculinity as a social role riven by the different codes of being and behaviour social ideology and social practice needs it to serve. The additional imaginative power comes from Malcolm’s frequent concerns about what is ‘inside’ him. Oft he declares he is merely a ‘brain’ to which his skull is a house, and his parents’ house vice-versa is but the same as his skull. There is much dark thought here about the relationship of flesh to brain to bone (the latter being reduced from skeleton to skull alone. I think Burnet years to write the novel that will separate the flesh, the bone and the brain in order to see how in fact they interact as apparently ‘one’ to make up the thing we call a self. At the moment, he still uses the literary mechanism of the doubles story, though even Stevenson insists that the existence of a Jekyll and a Hyde in the same metamorphosing body is no argument that a person is two things not one. He insists we are in fact ‘many’ in one – polymorphous. We need now novels that do less on doubles and much more to see the significance of distributed identities, played between social roles but also ideological positions, re-configuring them from the uses they have served in human representation.

That’s all for now. See I have lost interest in ‘the double’ in the interests of the polymorphous in our psychology as beings – where the animal, mechanical, spiritual and many other categories of being play a part and claim communality and diversity. I asked: ‘Do some themes in psycho-pathological fiction get overworked?’ Of course they do. We need novels that are not about crime and madness and hence psycho-pathologically. I liked Graeme Macrae Burnet’s 2025 novel Benbecula but we all need to move beyond this morbid fascination – how? I don’t know. Hence, I can only admire Burnet’s writing still!

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx

________________________________________________________

[1] Karl Miller (1985: viii) Doubles: Studies in Literary History Oxford, Oxford University Press.

[2] Graeme Macrae Burnet (2025: 7) Benbecula, Edinburgh, Polygon

[3] see ibid: 77.

[4] ibid: 8

[5] ibid: 76