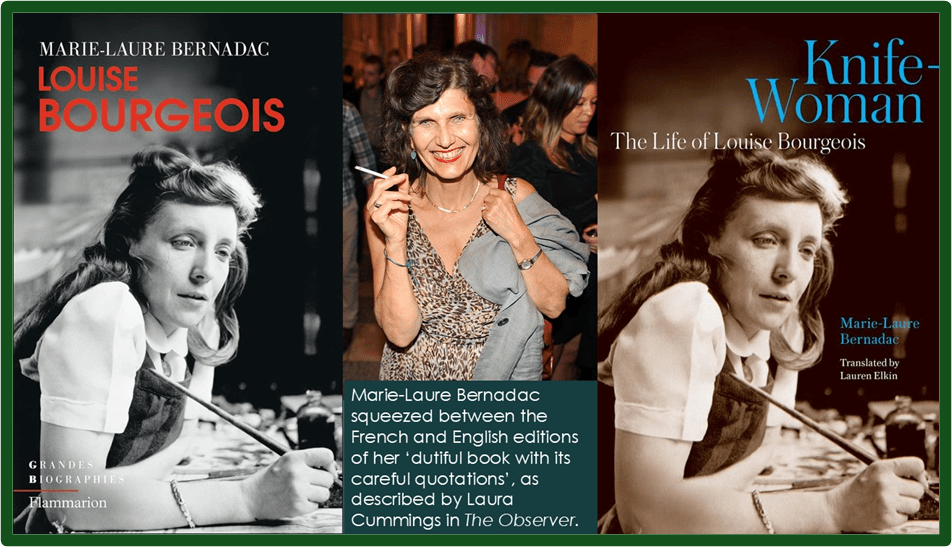

Deconstructing a life that seems to circle around complaints by a creative woman about ‘family’: Is that the function of biography about a ‘knife woman’? This is another blog on the challenging art of the biographer with reference to Marie-Laure Bernadac [trans Lauren Elkin] (2026) ‘Knife-Woman: The Life of Louise Bourgeois’. New Haven & London, Yale University Press.

It used to sound praiseworthy to write ‘a dutiful book with … careful quotations’, but it is not the case in Louise Cummings’ review of a biography that was originally published in French in 2019 as Louise Bourgeois, given the extra title (in the English translation, of Knife-Woman. But, first of all, let me give two reasons for this blog, other than the extant one of a prompt question that has allowed me to take the theme of why a life might be thought to be faulty by being full of, and driven by, a certain kind of complaint – complaints about ‘family’, the one you are born into and the ones that you elect to live in through that life. The first reason is that, since I first began to be conscious of modern art, I have been consciously troubled and fascinated by Louise Bourgeois. See my past themed blogs at these links: a 2021 ‘artist’s room’ exhibition at Tate Liverpool, on a 2022 Hayward Gallery exhibition of the woven fabric artworks, on a book on her Paintings, on the book constituted in fabric with Gary Indiana in the last year of her life, on seeing Maman again at Tate Modern in 2025. Secondly, I have a fascination with biography and commentary on biography. This follows comments on biographies of C. P. Cavafy and James Baldwin, each ploughing their furrows through a life with very different methods, tools and use of materials (see the links to those pieces on the biographical subject’s names above). This biography is like neither of those but can be defended, this time against Laura Cumming, with whom I usually have empathetic vibes, as the critic of Marie-Louise Bernadac’s biography in The Observer. Bernadac’s ‘life’ of Bourgeois is not like the Peter Jefferies & Gregory Jusdanis on Cavafy or James Campbell on Baldwin, but I sense that Cummings would prefer it to be more like the latter than the former, whilst I believe there is room to use the former’s critique of the kind of biography written by Henderson to justify Bernadac’s achievement, which i found considerable.

But first let’s see how Cummings critiques Bernadac, ‘damning with faint praise’ (the quotation below might look better in the original heroic couplets of Pope), where she does not rather condemn the writer’s approach openly.

The burden of Cummings dislike seems to be against Bourgeois herself: when declaring, as with other lovers of Bourgeois that she was not only a genius amongst sculptors but ‘an equally magnificent mythmaker’. Yet to express mythmaking in the form of saying that in her stories about her birth family her complaining version of things (such as this in Cummings first paragraph: “I was a pain in the ass,” she told Modern Painters in 1993. “when I was born, they abandoned me flat”, are just the way a narcissist storyteller spins myths, sure that the true version of events cannot make ‘a better story than the tale of abandonment Bourgeois gave every journalist from 1982 … until her death in 2010’. This is not the impression I get of Bourgeois in Bernadac’s account, and not just because Bernadac is over ‘dutiful’ to the memory of a late friend. But Cummings carries over her attack into what she believes is Bernadac’s parsimony with any detail that might reflect badly on Bourgeois, rather than those she complains about. She sums up the writing thus: ‘Discretion, prudence, professional tact: all these virtues mar her biography’.The professional tact arises from Bernadac own background knowledge of Bourgeois and those who survived her, with a duty to protect her heritage (even lining in the New York ‘brownstone’ lived in by the artist till her final hospitalisation and death:

Venerable curator of three Bourgeois shows, Bernadac was given access to the colossal archive of diaries, letters, loose-leaf observations and psychoanalytic writings “discovered” in the 21st century.

The reticence of Bernadac (attributed to Bourgeois too but not always) is shown according to Cummings across her relationships, about her father’s dath, the reasons for her sudden marriage to Robert Goldwater, her fears about her capacity in childbirth, or as a child-rearer, veering from overt need to be assured of these things to their neglect, her politics under McCarthy: but mainly the men, of whom, for example, Cummings says, ‘Goldwater has almost no presence in this book’, the reciprocation of Bourgeois’s passion in her affair with the MOMA director, Alfred Barr, and, most of, the sexuality of her late companion, whose penis was the model for late artworks, Jerry Gorovoy. The conclusion: ‘this biography is all too timid’.

Cummings decides that Bourgeois’ complaints about betrayal and abandonment by her birth family, which Cummings suggests is anyway, largely fictitious, inspire the grief and fury that sustain Bourgeois’ work. “All art,” she would tell pilgrims to her brownstone in New York, “is an exorcism”’. But note the certainty of Cummings use of quotation here, for I do not think that we can drive a consistent story through a biography by pretending that such a story tells of a unified development of a life and interpretation of that life. That is exactly what James Campbell does I stated in my blog on this life of James Baldwin without any timidity at all, driving forward his unified, in the words of his recent interviewers, his biographical take on Baldwin:

“the notion of Baldwin’s decline as writer from the 1960s, which is something you chart in Talking At The Gates”. It is a view contested in later critiques but Campbell holds his corner belligerently, saying most of these cases are ’meretricious’.[2]

I think Bernadac has justifications other than special pleading based on her status in the over-protective art world’s concern for ‘reputations. What I said of the modern Cavafy biography of Jeffrey and Jusdanis could in my view be said of Barnadac, and much more fairly and less censoriously than Cummings hints if failure:

… I think this biography opens the doors on the unsaid because it refuses the singular narrative line and authoritative control of the life as if it were one theme. For me, it is a very good biography …[3]

Marie-Laure Bernadac tells us, after all, that Louise Bourgeois was not, as Cummings seems to miss, to the detriment of how an understanding of Bourgeois’ life can begin with uncertainty about single representations of its multiple latent and blatant meanings, a person of unified consistent meanings. She ‘worked constantly with paradox, often saying one thing and its complete opposite, as a matter of course’, she tells us.[4] And this is true of her art, which Cummings thinks this writer understands better than life-writing, as of her life. To me it speaks out of the biography, not least in its breaking sequence to recover ground more fully when it needs to, partly to show how interpretations of a memory varied for her, as she does when she decides to collect in one sub-section the fragments that add up to the figure of her family au-pair, Sadie Gordon Richmond in Chapter 1: ‘Childhood’. Yer Bourgeois reinterprets Sadie later in her life from a ‘double-betrayer, requiring complaint, to someone who possibly redeemed her from her father’s sexual attentions. This as[pect of the work is most important with regard to her husband, Goldwater, about whom she constructed various myths – not only one that relegated him to the unrecorded and silent in life-histories that Cummings sees. He isn’t absent to me in this book, just ever skirting margins, which is how it is with some people. And I find that understanding by paradox central to Bourgeois on her art as well as the art itself. Tale this comment by the artist on her ‘cells’ art series:

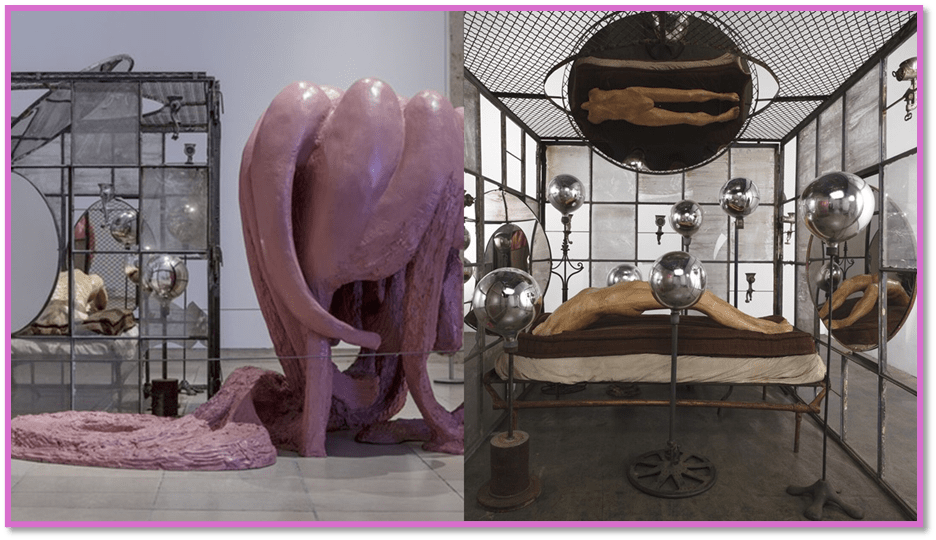

‘The Cells represent different kinds of pain: the physical, the emotional and psychological, and the mental and intellectual. Each Cell deals with fear. Fear is pain […] Each Cell deals with the pleasure of the voyeur, the thrill of looking and being looked at’. [5]

But let’s not leave Cummings on the Bernadac rendering of a life, before we come back to ‘cells’ in the art, before we show just how driven some writers, especially novelists like Cummings, can be in driving one interpretation through a life as they would have written it, the way I associate with James Campbell. It concerns the reading of photographs in a biography. The photograph on the left below, Bernadac refers to thus: ‘In Nice, on the promenade des Anglais,it seems as if Louis and Sadie are a couple and Louise and Pierre their children ….’ [6]

Cummings uses this as an objection to the biography saying: ‘To Bernadac, a group shot with father, brother and governess in Nice resembles a couple with their offspring, though it does not to me. Sadie looks away and M Bourgeois stands askance’.Bernadac writes plainly but with nuance. She does not, to my mind say that this is a resemblance of a ‘couple’, though I think Cummings is just plain wrong to believe that some wives do not ‘look away’ whilst their husbands stand ‘askance’ but that it is surprising that Bourgeois as a young girl recorded no trace ‘of the relationship Louise’s father was carrying on with the young Englishwoman’. Only later did Bourgeois identify the affair and its consequences on her and the fragile Pierre. Far from being a lazy biographer, Bernadac is pointing out that historic memories were fluidly interpreted by Bourgeois throughout her life, where a attentive young girl might have seen the avoidance of the adults in this picture as incriminating. The photograph on the right Cummings argues the the young Bourgeois having ‘scratched out her own dead-centre face’ is an ‘acute destruction’ which ‘turns the image into an enigma’. Here she seems to be blaming Bernadac for not seeing its significance and instead accepting Bourgeois’ explanation that she scratched out the face because she didn’t like the haircut she had on the snap. This biographer cannot win against this critic – accused of over-interpreting and under-interpreting by turn, because the book does not tell the unified narrative Cummings desires from it.

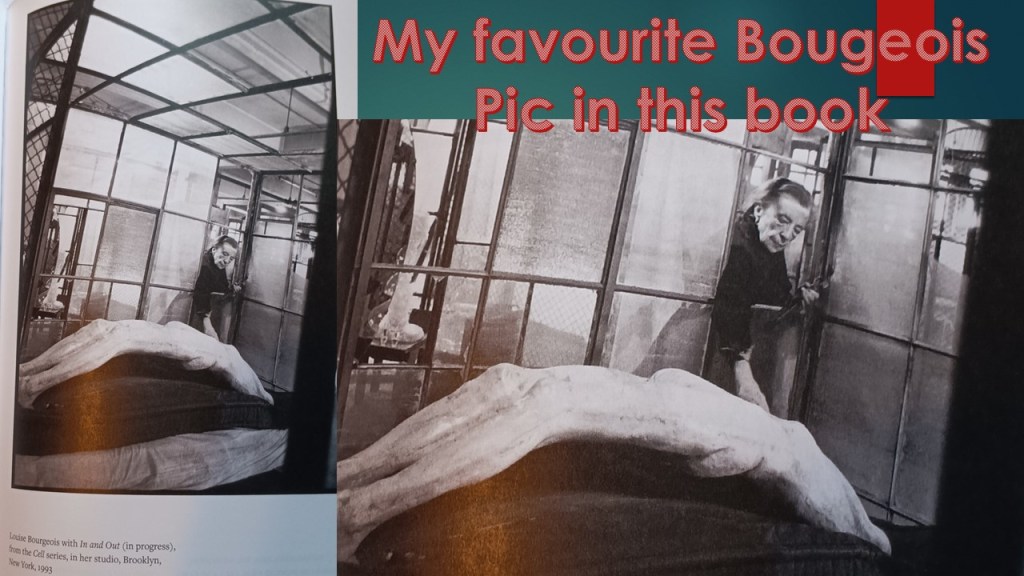

My own favourite picture from the book is one that aligns me with its author’s concern to concentrate on the way art served many purposes for Bourgeois other than ‘exorcism’ of the past alone. It shows the artist working on the best known Cell, known as In and Out, in 1993. Hanging into the geometric cell through one of its unpaned windows, Bourgeois seems to situate in it more precisely the arched nude figure (modelled on Jerry Gorovoy, minus head and feet but with Jerry’s pronounced penis. It shows that Bourgeois got into the art’s contemporary meaning, not just used it as an emblem of imprisonment, for ‘cells’ also are the building bricks of life not just emblematic prison components.

See the full work, after this photograph and note how little the gestures and gazes of a picture can tell you whilst fairly usable as suggestive of meanings made or missed. Everything overwhelms with its multiplicity of features and possible narratives, because they allow too many perspectives on what might be seen in them – partial or more full, leaning into just seeable interiors of different kinds and with different tools – mirrors (a huge version of a Claude glass even). With multiple perspective come multiple interpretive potentials and ways of frame-working our vision in some context, very few of which need to be traced to the autobiographical, although Bourgeois taunted us with this strong possibility of this being access to an artist’s life.

In my view, Bourgeois is about the paradoxes Bernadac makes much of, and allows to flutter in the many quotations she gives. Between and within these are paradoxes and contradictions, and refusal of the ability to name any phenomenon simply with one name, idea or domain. Go back to the Cells quotation above.

The Cells represent different kinds of pain: the physical, the emotional and psychological, and the mental and intellectual. Each Cell deals with fear. Fear is pain […] Each Cell deals with the pleasure of the voyeur, the thrill of looking and being looked at

Ask yourself ‘what’ do cells ‘represent. They are ‘different kinds of pain’, but ‘fear’ is ‘pain anyway, so does that too have the same ‘different kinds’? Moreover if fear is pain, is pain fear? The two way equation could but need not be there. Is fear a subset of ‘pain’? And if the cells represent this, how do they also ‘deal with’ the pleasure of the voyeur, whom anyway, seems to get ‘pleasure’ from being their own object of view. No autobiographical narrative in the world can explicate all this as he intention of the art’s strain towards meanings. For Bourgeois is not tied into the notion of the singular subject talking its own biography. She is nearer to seeing the ‘subject’ itself, as an architectural and archaeological thing, made up of layers and segments, a gaze that travel multi-directionally only to find there is no sum to the parts it sees and tries to put together. Hence her concern with eating (and the variant of that in cannibalism) is another fascination with articulate but also inarticulate structures, that decompose in their composition (she believed the penis was such a structure – the real focal symbol of male vulnerability, rather than power – hence La Fillette in Mapplethorpe’s capture of it carried round with her).

The sculptural installation The Destruction of the Father might reference Louis Bourgeois, but it references much more the Lord’s Prayer in the Psalms: ‘Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies:‘(psalm 23, line 5)..Bernadac says that Bourgeois herself said the piece referenced ‘family meals and the ambiguous love/hate relationship that she experienced with her father’. But it is so much more, isn’t it. It makes ironic the terror of celebrating in the spite of one’s enemy or enemies, it recalls various structures – a table, a bed, an altar and a bier for a corpse. From certain views the suff spread on the table seem like the articulated parts of a flayed body, with a spine down its middle: ‘bloody entrails and severed limbs’. [7]

It may evoke the penile or the breast – the transitions between sex / gender. Many of the pieces are like excrement. This is not just the father but the self. For Bourgeois one great paradox between disgust and desire, revulsion and desire. She later said, tying up symbols of birth, sex, food and excrement in her work:

“I have a morbid attraction to the shit, covering up for the revulsion. Revulsion at everything including the self”. [8]

Things, including emotions, and their covers allow for expression of paradox, for revulsion that coexists with attraction and vice-versa, but in the end, perhaps between covers and things there is little difference, in Le Trani Episode (19720, the ‘large coat stands in for the father, authority’, but perhaps authority is no more than a covering coat for something truly absent. You can’t get to Bourgeois through biography alone, you need (as this biography does) to respect the various avenues that stories and symbolic processes take us to – all of them.

I loved this biography. Not about a load of complaints at all – but about restless analysis.

Bye for now

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Laura Cumming (2026) ‘The fierce life of Louise Bourgeois’ In The Observer online (Wednesday, 14 January 2026) Available at: https://observer.co.uk/culture/books/article/the-fierce-life-of-louise-bourgeois

[2] Despite the literary establishment, biography can be done differently. Reflections on James Campbell (1991) ‘Talking at the Gates: A Life of James Baldwin’. – Steve_Bamlett_blog citing Douglas Field & Justin A. Joyce (2021) ‘How Long Blues: An Interview with James Campbell’ in James Baldwin Review DOI: https://doi.org/10.7227/JBR.7.10 Number: Volume 7: Issue 1, 167 – 183

[3] It was this blog, of course! It is on Peter Jefferies & Gregory Jusdanis ‘Alexandrian Sphinx: The Hidden Life of Constantine Cavafy’. – Steve_Bamlett_blog.

[4] Marie-Laure Bernadac [trans Lauren Elkin] (2026: 6) Knife-Woman: The Life of Louise Bourgeois New Haven & London, Yale University Press.

[5] Bourgeois cited in chapter head by Marie-Laure Bernadac ibid: 257.

[6] ibid: 28

[7] ibid: 220

[8] ibid: 266

One thought on “Deconstructing a life that seems to circle around complaints by a creative woman about ‘family’: Is that the function of biography about a ‘knife woman’? This is another blog on the challenging art of the biographer with reference to Marie-Laure Bernadac [trans Lauren Elkin] (2026) ‘Knife-Woman: The Life of Louise Bourgeois’.”