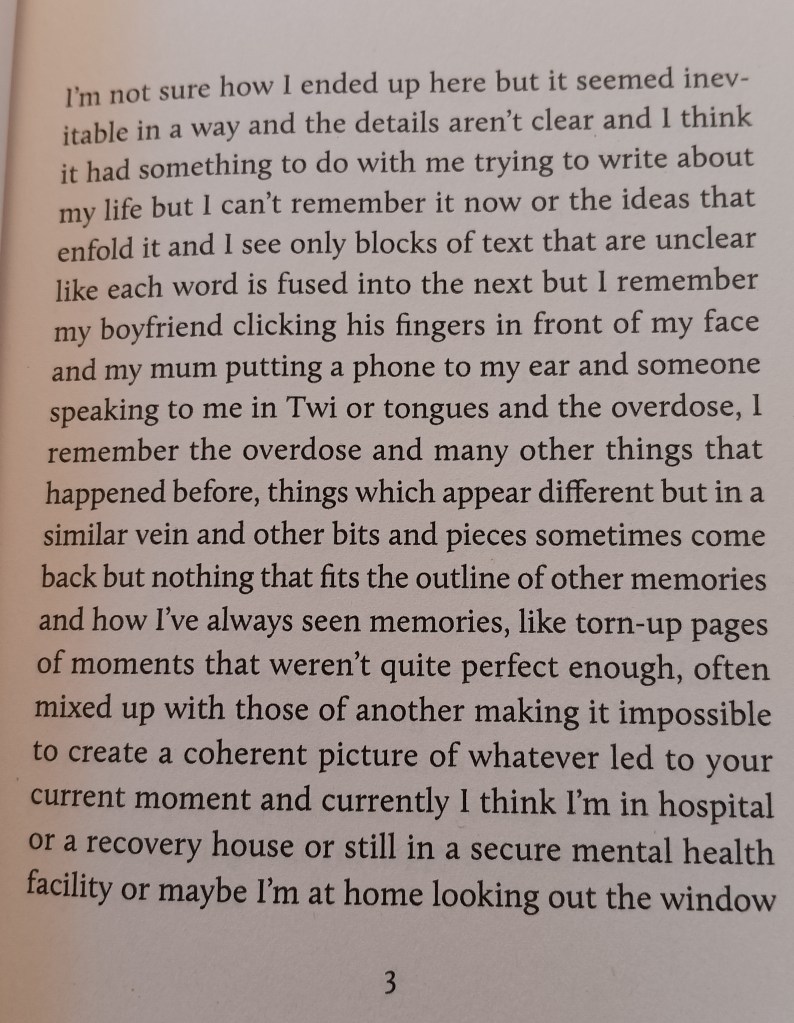

Have you ever felt that so much depended on a reading of what is in front of you? I have just made a first reading – fast and furious – through the proof text of a novel not due for publication until, I think, September 2026, Derek Owusu’s The Recovery House, which will be published by #Merky Books, Penguin. Beyond the few words from the first chapter in the title above and the first page with its beautiful too-fatigued-to-end sentence below (it does end together with the ‘chapter’ (if that is what it is to be called at least for the sake of reference, and if not with a (.) ‘full stop’ on the next page, a few lines down), I do not intend to give quotations from the text, which may change (and be proof-‘corrected’) before publication.

Derek Owusu (proof dated 2026: 3) ‘The Recovery House’ #Merky Bookes, Penguin Random House.

Instead I want to record my first reading (I will read the proof again a few times but will not review the book until its final publication when I buy a published first impression) as a report of the visceral, sensual, cognitive and emotional impact of the writing, and all of these mainly as operative through memories and other mental patterns and acts of pattern making, including plotting the novel (especially in his novel Losing the Plot, referred to in my blog linked here)

Moreover, that reading needs to comprehend my desire, accompanying whatever the ‘activity of reading’ is that I have, am and will continue to ‘read’ in a way that yields some sense of communion with it. And by it, I mean its characters, including (mainly in fact) the first-person narrator, whose partial life it tells in excerpt (an excerpt of communal living under the promise of ‘recovery’). And perhaps too and much more communion with an author I have followed from his first fine novel, That Reminds Me (I even wrote one of my first very thin blogs on him in 2019 when the book appeared – see this link). In all of his novels, Owusu plays games with the premises of autobiographical, fiction, and the biographical ‘other’, such that no certainties hold about who precisely is the ‘I’ referred to by the first person narrator. In the page / sentence above the narrator attributes their current predicament ‘perhaps’ to ‘me trying to write about my life’, but whose life? And anyway is ‘writing about my life’ another thing entirely from ‘my life’ or the I who reflects on either the life or the writing about it.

It is even difficult to be clear about what I mean by all that, perhaps but I think that failure of clarity is itself inbuilt into the reading experience, for even the narrator moves from talking about what ‘I’ did to the impersonal pronoun ‘it’, and it has no more clarity of reference that I, the personal pronoun. Take this: ‘I’m not sure how I ended up here but it seemed inevitable in a way’, for here refers back, a first reading would suggest to ‘how I ended up here’, and it’s ‘inevitability’. But as we read on, ‘it becomes more difficult to reference back to any one idea. Try the sequence here:

... it seemed inevitable ... ... I think it had something to do with me try to write about my life but I can't remember it now or the ideas that enfold it ....

By the time we try to process what the it that is ‘enfolded’ by ‘ideas’, we have had many choices for the intervening ‘its’ in the prose. Is ‘it’ my attempted act of writing, the writing itself, or, ‘my life’that is ‘enfolded’ by ideas. And more than that, for it may be that as ‘it’ becomes a thing that I attempt to reference inm and from memory, its lack of specific identity has a lot to do with those failures or gaps in memory.

And when the person who once wrote something (perhaps autobiographical) tries to remember, they see only the same thing the reader may feel they are seeing, and perhaps not reading – for ‘blocks of text’ is perhaps what writing is, both before and after it is read and / or comprehended by someone, if either should in fact happen: ‘I see only blocks of text that are unclear’. Reference (to enfolding ideas perhaps) now begins to unfold into different possible meanings or referents, for is text ‘unclear to visual capture by the eyes or does it lack clarity cognitively by the reading subject – even the explanation that ‘each word is fused into the next’ could mean in either of these ways depending on whether ‘fused’ is a physical reality (which seems unlikely) or a metaphor for the subjective appearance of the text, or a metaphor for the reader’s inability to distinguish the meaning of even basic words – like ‘I’ and ‘it’, for instance.

When the narrator recalls their mother putting the phone to their ear the voice heard is ‘someone speaking to me in Twi or tongues and the overdose, I remember the overdose and ….’. The lack of punctuation allows for the moment ‘the overdose’ to read as if it were at least an alternative to what the narrator heard from the phone’s speaker, whose other alternatives were Twi (an objective Ghanaian language), or that which is hear when the inspired are ‘speaking in tongues‘ (which may be talking in many languages (for which the archaic term is ‘tongues) or the voices of a holy intermediary with the supernatural (as at Christian Pentecost) or as ‘glossolalia’ a symptom of a mental illness To some (though that is queried by others) according to modern listings of mental health symptoms. It may be that the way language diverges to multiple reference in such prose is also enacted glossolalia, although, as I have shown the meaning of that phenomenon remains unfixed. Nevertheless, we will see this passage is the beginning of a text where ‘overdose’, or other forms of self-risk are spoken constantly.

As subject and object too become difficult to distinguish in this in-determinant sentencing, so does the foreground and background of the prose description. After all, the narrator has ‘ended up here’ but is ‘here’ really knowable. Even by the end of the page, the narrator cannot distinguish whether ‘here’ is ‘hosp[ital or a recovery house or still in a secure mental health facility or maybe I’m at home’. If we cannot be distinct or ‘clear’ is that because of a ‘disorder of consciousness and cognition’ or because telling the things between ‘things’, even the thing that names ones subjectivity gets lost when when they, like the overdose are simply ‘many other things that happened before, things which appear different but in a similar vein and other bits and pieces’. By now I even wonder if the ‘vein’ named here is a metaphor for a stream of similitude or the vein into which perhaps an ‘overdose’ could be administered.What is certain is that life or its record or the relation between both is fragmented.

After all, for this narrator ‘memories’ are ‘like torn-up pages of moments that weren’t perfect enough, often mixed up with those of another making it impossible to create a coherent picture of whatever led to your current moment …‘. Note how memories are ‘often mixed up with those of another’ too. i have already spoken of Owusu’s game of mixing autobiography with ‘other’; (or ‘another’s) biography and the same happens here. In the novel there are many points in a similar vein between the narrator’s life and the author’s (the number of novels written, the collection of Black writes they edited (Owusu’s is the great volume Safe referred to in this blog) but they not only ‘appear different’ but are so. Similarly with the sexuality of his narrators. I have spoken about the unsettling (non-determinant) nature of that in his last novel Borderline Fiction in a blog linked here and on its drafts (that blog here). Hence when the narrator speaks of having taken a ‘boyfriend’ in thgis novel on our page, no certainties lay there – as indeed they don’t for the boyfriend in the narrative, who is restricted from visiting and may be abandoned on the narrator’s discharge). But the love of the narrator for ‘Joy’ (the feeling and the woman) may not be indicative of a sexual choice at all either.

The key words in this passage will pattern themselves throughout the novel, not least the word ‘home’ as a signifier of security (or otherwise) or of another’s attempt to thrust security and containment on one. Homes and houses, including a ‘house built on sand’ in the epigram to Part 3 of the novel – silently (at least in this proof copy) appearing from the King James Version of the Gospel of Matthew 7 (27). I will consider this again, when i write more fully on the novel proper. But pattern-recognition is a ‘writerly’ and ‘readerly’ skill in art, only realised in a reading where varied subjectivities commune in the object that is a text. Subjectivities are, of course, malleable to input. The ‘Author’s note’ to this novel perhaps suggests this, wherein Owusu says:

For a better experience of The Recovery House, please listen to ‘Zombie’ by The Cranberries at least two to four times before going beyond this page. Thank you.

The strategy let me tell you, works: this strategy gets that song right into your heard, and grows something like an earworm that continues to slide into and around one’s head’ only to be triggered fully when the narrator first hears the resident or ‘patient’ in the room below him, Joy or joy, singing ‘not the entire song, just the chorus over and over again’ (page 10). He requests the nurses to print off ‘the lyrics to the ‘Zombie’ song which they print on both sides and I read the same night and become confused as to why the girl in the room below me keeps singing it because the lyrics seem to be about war’. (page 12). Read those lyrics yourself – though note how situated the reading experience of the narrator’s is – in a text printed on both sides of one sheet, as the one below is not. Nevertheless, we can guess that the lyrics or their choric elements will not stay with that reading in any reading for anyone for all times and in all spaces. And differences will not all depend on whether or not the reader picks up the reference to the Irish Easter Rising of 1916.

Zombie, song by The Cranberries

Another head hangs lowly

Child is slowly taken

And the violence caused such silence

Who are we mistaken?

But you see, it's not me, it's not my family

In your head, in your head, they are fighting

With their tanks and their bombs, and their bombs, and their guns

In your head, in your head, they are crying

CHORUS:

In your head, in your head

Zombie, zombie, zombie

What's in your head? In your head?

Zombie, zombie, zombie, oh

Do, do, do-do, do

Do, do, do-do, do

Do, do, do-do, do

Do, do, do-do, do

Another mother's breaking

Heart is taking over

When the violence causes silence

We must be mistaken

It's the same old theme since 1916

In your head, in your head, they're still fighting

With their tanks and their bombs, and their bombs, and their guns

In your head, in your head, they are dying

CHORUS:

In your head, in your head

Zombie, zombie, zombie

What's in your head? In your head?

Zombie, zombie, zombie

Oh, oh, oh, oh

Oh, oh, oh, eh-ah, ya-ya-ow

Songwriters: Dolores Mary O'Riordan. For non-commercial use only.

When the chorus is reprinted as an intervening epigram in the book, the stress is not on the words but the way they are stretched out by the music into a kind of different view of what it means to be ‘in your head’:

In your heeee-ead, in your heeeeeeeead

Zombie, zombie, zombie-ie-ie-ie

What's in your heeee-ead? In your heeeeeeeead?

Zombie, zombie, zombie-ie-ie-ie (page 57)

The whole issue of this is to problematise both writing and reading as means of access and egress (both writing and reading are each egress and access and vice-versa) to ‘your head’, which is a place of unseen patterns and pattern-making.What stays persistently, and with the ability to change its visual and audible structure, in your head is very much on line with this book’s recording of both writing, and the reading of our own writing (sometimes in memory only) or the sharing of writing and reading stories with others. Many books are read (and not read) in this book: starting with Bibles in distinct types and with different owners and associations thereby, including The Chronicles of Narnia and The Magic Mountain, amongst other books, the principle of whose selection may be both random, as the narrator feels the ‘pile’ of books brought into him is,and highly determined, simultaneously.Some passages go to basics – what, for instance, makes a written lyric ‘poetry’ or ‘music’ and why might the exact nature of that writing make use of these terms for it contested (by ‘serious poets’ for instance) , or what in words evokes feelings, such as ‘being alone’ (page 45) or hearing a voice in your head, perhaps that of God that joy hears. Sometimes all these dynamic relations are in the prose, where a window looks out to the world but no more than do your eyes – for they are windows which actively reflect: ‘I’m trying to read or remember … or I’m looking out the window watching people and what’s in your heeee-ead is how it seemed to sound in your heeeeeeeead.’

i have quoted more than intended because the prose evokes so much as a memory, i have to steady myself by putting in some of the original to make sure I have not invented its beauty in my head. You will see I have not. this book will be a publishing adventure. And, of course I can’t commune with Derek Owusu, but i can aspire to that.

That’s all till i read the published form. can’t wait.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

PS: I will write the following words to Derek, who I do not know personally, via his agent:

‘Dear Derek

Your book arrived and your kind note. Please do not think I feedback with disrespect against you note that there is ‘no need’ but I do on (give webpage address). However, if what I write offends without any intention or foresight to do so, please let me know and I will amend or delete as require. I have no filter for publisher’s protocols either, so if I have been in error in sharing this publicly, again I will delete on your request (until such time as I can re-present in appropriate times – if there are any. This book should shake literary foundations.

Love

Steven’

One thought on “‘I’m not sure how I ended up here … and I see only blocks of text that are unclear like each word is fused into the next …’. Reading is an aspiration towards a communion.”