The white literary establishment once considered itself to be colour-blind, dealing equally with all writing free of categories such as ‘Black writing’, as distinguished from ‘White writing’, neither of which this establishment considered valid categorisations of the written literary text. For a literary biographer however it may be possible to tell the story of black lives that imposes a colour-blind status on the evaluation of writing that inevitably colonises and appropriates its independent values by using this supposed objective standard to assess the direction and value of a life and the moments of that writing life which readers should value, regardless of their race, skin-colour or ethnicity, and the prevailing hegemonic interpretation of the persons whose life is told. This blog revisits an argument in an earlier blog that focuses on ‘the artificiality of biography as a type of writing’ in choosing to tell life stories differently.[1] I will aim to illustrate one way in which that artificiality matters by arguing that James Baldwin’s best known biography by James Campbell (1991) Talking at the Gates: A Life of James Baldwin, London, Faber & Faber, appropriates to colour-blind (in fact ‘white’) perspectives the life-story of a black queer hero.

In an earlier blog, I critiqued the view of a self-styled representative of a literary establishment, Michael Londra, who speaks of the most recent biographers of the poet, Constantine (or C.P.) Cavafy. Londra suggests that the authors, Peter Jefferies and Gregory Jusdanis, use the chronological and other gaps in the life-records of the queer Egyptian-Greek poet they write about to point out that the standard literary accounts of his life, and work, deracinate it in ways that render it toothless as an interpretation of a world of beautiful diversity. They accuse the biographers of being faddish reinventors ‘of the wheel’, and coming up with something inadequate instead of the time-honoured conventional format of literary biography: ‘Overwhelmed by the magnitude of their project, the authors’ self-confessed “discomfort” with biographical narrative feels more like an admission of defeat’. To call their methodology an ‘admission of defeat’ is to suggest either that had failed in the capacity of biographers to tell a whole and sequential story about their subject, and to dismiss their claims that the desire to tell ‘a whole and sequential story’ is a flawed project, open to abuses of supposedly holistic interpretation. Londra then sees no reason that the conventional biographical form should be abandoned and sees any case for doing so as reflecting badly on the biographers’ own knowledge, skills are values, though his statement of that point is never explicit. He writes:

Indeed, the “facts of Constantine’s life are…unremarkable and very straightforward.” That said, Jusdanis and Jeffreys encountered other difficulties: the “physical absence of evidence, the gaps in his records, and our own discomfort with traditional narratives of life stories.” For these reasons, the authors opted to reinvent the wheel: “we decided not to follow a standard ‘birth-to-death’ chronological direction…[telling] a circular narrative through various thematic sequences.” This enabled them “to draw attention to the artificiality of biography as a type of writing.”[2]

I could perhaps return to the main biography of Cavafy prior to this by Liddel, but I do not think this would illuminate as well the dangers of holistic interpretation in chronological biography as much as an older biography of the Black Queer artist, James Baldwin by James Campbell. Campbell is very clearly a flag-bearer of the British literary establishment, despite an early start in the championing of a distinctly Scottish literary voice – he is a Glasgow lad by origin – as analogous to a ‘Black American’ voice. Moreover, his stated belief in his prefatory ‘Author’s Note’ that his book too fails (but rightly so in his view) to be a definitive holistic picture of its subject and is instead ‘a host of sketches and perceptions aiming towards a definition, yet finally backing down from one’. He quotes as his justification Baldwin’s own statement (probably, we assume, to Campbell himself, for there is no reference) that ‘No one … can be described’. [3]

But there is a more deep and slow moving current of holistic grasp of the subject in this biography, based precisely in the right assumed by the author to presume a personal knowledge of the author, as people who call themselves the subject’s ‘friend’ sometimes do, that surpasses the grasp the author (or anyone else) has of himself as a subject. Slow moving deep currents can be dangerous and can drown their subject in interpretative acts that the subject themselves, being dead as the subject of biographers oft are at point of the biography’s publication, cannot qualify, edit or change. The subject is appropriated in this kind of holism more than any other, especially if there can be no reflexive machinery which makes the interpreting biographer visible to the reader in ways that allow their own subjective input to be discounted (or at least taken into account) in any reading of the biography, as in the case in the use of reflexivity in qualitative research of other kinds.

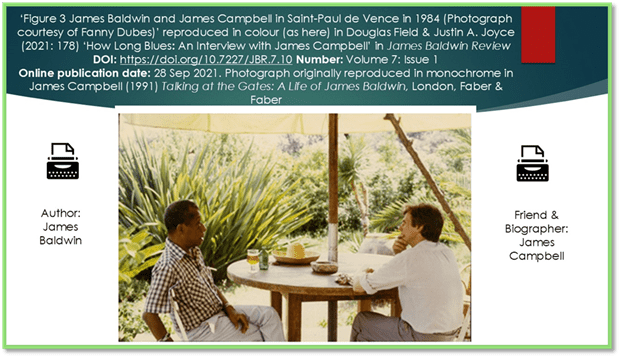

Now I should admit that this biography is rather originative in making the relationship between Balwin and Campbell part of its machinery and in a way it is difficult to miss. Here a blogger, ScottManleyHadley (sic.), on that use of relationship in the biography’s method of exposition below, although the point is pre-empted also by the fact that Campbell uses a photograph of him conversing with Baldwin in the latter French home (it is the introductory photograph in this blog) that will also become a chapter in itself:

There are a few things I like more than a biography with a narrative twist…

The twist in this excellent literary biography of the late unpunctual James “Jimmy” Baldwin is that the much younger Scottish literary critic James Campbell had actually known him in real life, if peripherally and only towards the end of Baldwin’s career when his critical star had dimmed, but still! A real life connection! Phone calls and a few dinners! A couple of pieces published by Campbell’s (then) magazine… A real connection!

It’s not much of a twist, tbf, I know that…

It’s not like Campbell was a significant lover or a critic and editor who somehow ushered Baldwin into a late career Renaissance, but it’s enough of a relationship for me to impressed by in in the final section of the book! (my italics – the author’s bolding) [4]

Though I can’t do it myself, I so admire bloggers who blog as it was once believed one should do; with a personalised and informal style. This section of the review gets the relationship’s measure accurately I think, though for me it is precisely the effect of impressing upon the reader the sense of a knowledge based on relationship (that emphasised by the constant reminders of Baldwin’s bad faith unpunctuality in keeping to meeting appointments for example which ScottManleyHadley so cleverly picks up) that leads to the dangers of the biography, particularly with regard to what I believe is a false representation of the identity politics of the book – both of race and sexuality. In a way Campbell makes the point about the way his views of race differ from Baldwin’s at the later stages of his life is enough to pass for a measure of reflexivity. But in another way, these differences are throughout used to diminish both the latter racial identity politics and Baldwin himself.

Before I enter onto this ground though I want to register my shock at that part of the book where the author and subject meet (chapter 24). After outlining the negotiations between himself as student (and latterly editor of the New Edinburgh Review) to gain a new essay from Baldwin, at a student publication budget price, he tells of the first appointed meeting with Baldwin in the flesh (Baldwin of course was late and had forgotten the arrangements made). Forced just to loiter in the square watching a game of boules, he writes of his first sight of the man not in a photograph thus:

Within quarter of an hour, Baldwin appeared at the junction about fifty yards away: small and slight, in sunglasses and short-sleeved shirt, with a mincing walk; looking all around, he seemed a stranger himself. My mental image of him was out of date. With grey in his hair, he was no longer the young man I had read and read about.[5]

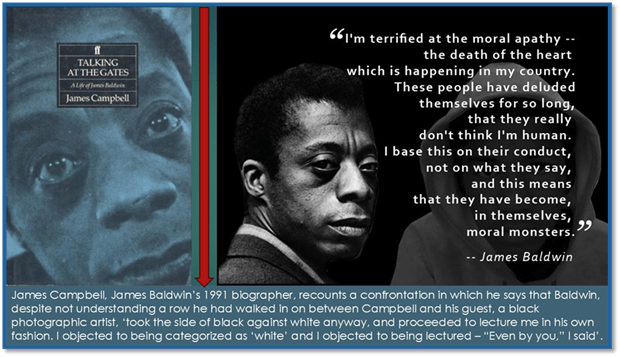

On first reading this I was shocked by the narcissism of this passage that seems to employ descriptions evocation of stereotypes of both older males, as compared to younger ones, and queer men – for the referent of ‘mincing’ is not a particular style of gait nut of an ‘effeminate male’, if you value such categories. Any suspicion that is slack and thoughtless writing dissipates as the chapter continues to reveal Campbell’s evaluation of the changed phenomenon that was the later age period of James Baldwin in his paradigm of the life’s arc as a decline, both as a writer and icon, but mainly as a writer. Campbell constantly shows his disappointment with Baldwin he meets, as opposed to the one he had read and read from his earlier writing in this chapter. Baldwin emerges as a defensive character justifying his tolerance for non-literary celebrity and fame, his inordinate whisky-drinking and late rising, collusion with fashionable black and gay male ‘identity theory’ at the expense of a qualitative approach to writing based on literary criteria alone and his capacity to appear to venerate ‘black writing’ and writers as if a thing reserved from critique. The most stunningly unpleasant episode of this is summarised in the slide below:

Here, James Campbell recounts a confrontation with an unnamed black photographer (and his wife), who was a guest of James Baldwin in which he told the photographer that his theories of white response to black writing ‘though neat were worthless’. Understandably the photographer retaliated and eventually opined to Campbell that he, as a white male, was incapable of understanding the strategies by which black writing was marginalised by the white academic and journalistic establishment. Campbell retorted querying the photographer’s commitment to genuine understanding and taking offence at being labelled as ‘white’. Returning to the room – to find his guest being berated by Campbell in racial terms (a point about everyday Campbell doesn’t seem to notice) Baldwin ‘took the side of black against white anyway, and proceeded to lecture me in his own fashion. I objected to being categorized as ‘white’ and I objected to being lectured – “Even by you,” I said’. Perhaps this is a moment of reflexivity, against which the biographer’s biases, can be seen and taken into account by a reader but I think not. Campbell’s position is ‘rude’ and categorically ‘racist’, whether he likes those labels or not.

Of course, Campbell never seems to object to Baldwin calling him ‘Baby’, a term that might be read as sexualising him, but in an interview with Douglas Field and Justin A. Joyce, the editors of James Balwin Review, on the publication of the 2021 revised edition of the book Campbell makes references to how he needed to escape Baldwin’s sphere of influence or have a specific role (vis-à-vis Baldwin’s writing as a collaborator or ‘editor’) to avoid appearing as what he calls a ‘hanger-on’, or worse ‘the latest hanger-on’, a point that leads him to be suspicious of why Baldwin ‘liked’ an ‘arrangement’ and ‘would have liked more of it’.[6] But the main point of differentiation emerges from and justifies Campbell’s view that Baldwin’s life and writing both mark what Field and Joyce call, rightly I think in terms of the arc of Campbell’s biographical take on Baldwin, ‘the notion of Baldwin’s decline as writer from he 1960s, which is something you chart in Talking At The Gates’.[7] It is a view contested in later critiques but Campbell holds his corner belligerently, saying most of these cases are ’meretricious’.

The case for this decline is tied to Campbell’s belief that Baldwin once thought, acted and wrote as Campbell himself continued to do with repugnant disdain for ‘identity politics’. He puts it neatly thus in the interview: ‘Literary criticism has been corrupted by identity politics’. ‘Corrupted’ is a strong word but it lies at the base of the contest with Baldwin’s guest for favouring a superior understanding of white strategies against Black people in which words used must avoid offence of the person they are used to describe: what Campbell calls he ‘victimological pandemic’, a case of mauvaise foi (or ‘existentialist crime’) he argues that replaces the honest attempt a writer should make to produce ‘an honest report on his feeling’. [8]

I suppose here I feel caught in Campbell’s trap for one of the most meretricious accounts of Baldwin as a writer of identity politics he finds in Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro, a cross-generic artwork I have found in an earlier blog very appealing and beautiful (see this link for my blog).

Campbell argues that the verry title of this work is anachronistic biographically, since the title is based on a rather different expression by Baldwin: “I was never going to be anybody’s nigger again”. The film, he says, panders to not offending in order to cut off the connect to the actual surface of Baldwin’s expression in his own language as a writer primarily not a Black icon. I disagree with Campbell for I do not believe there is a binary between the finding of a Black voice and sensibility that is not an essence but an emergence from the existence of long-ranging history, and its cancellation from white culture. Likewise, though I am not a fan of ‘positive images’ of the previously marginalised, I do not believe with Campbell that If Beale Street Could Talk, as a book or film, is any the less impressive than artworks who use stereotyped positivity to produce romanticised racial, gendered or queer statements just short of the balance of the great literature of ‘rounded characterisation’. What Baldwin lost as he aged Campbell thinks is ‘this high modernist sense of “writing on the behalf of the energy of literature itself”’.[9]

The high calling of literature, as opposed to JUST writing is what Campbell felt he found in Baldwin pre and sometimes in the 1960s, writing guided by literary precepts and ‘high culture’ (and its necessary élites, be believes) not by avoidance of ‘even a micro-suggestion of racism or sexism’. That way lies, he says, ‘the demise of reading’,[10] and those habits defended by him as the self-styled representative of those ‘burdened by a literary-critical tendency’.[11] The self-satisfaction of the wording of that really irks me though I do believe in literary criticism nevertheless. Literary form is self-sufficient, he argues and the modernist sense of the literary genius still has legs.[12] Queer studies, he argues is largely incomprehensible.[13] This again cuts across my liking of some modern contributions to Baldwin studies, and to the work of a writer who crosses the boundary being literary criticism (of a higher order than Campbell) and the necessity of rendering the queer less invisible, in Colm Tóibín (2024) On James Baldwin, for instance (see my blog on this here). Moreover, I don’t think I am against the ways in which literary figures become iconic, as I suggest in my blog on Neil Blakemore’s new novel, Objects of Desire, in which Baldwin has some status, although this would put me in the pit that Campbell reserves for ‘Philistines’.

Having said all this I rather rate Talking At The Gates, if not enough to get the 2021 revision, which barely revises the text but puts more evidence of Campbell getting about a bit in the pre-internet days of travelling and interviewing literary critics in the easy-going old Times Literary Supplement.[14] There are lots of pluses that come from his deep investment in literature (readings of still unpublished material for instance) but I balk at precisely the way Campbell deals with the ‘gaps in his comprehension of Baldwin by just avoiding them; such as Baldwin’s multiple suicide attempts and his pressured need to promote a way of living based on touching. There is a sense that the following respect for privacy is really a fear of that that lies outside conventional thinking, and the repression of emotionality.

If I had come into possession of some intimate information, would I have used it? I’m not sure. The same goes for detailed discussion of his mostly unhappy love affairs. Is it any of my business? Is it yours? Some things remain private after death – …[15]

And some things REMAIN REPRESSED and MARGINALISED. Some people prefer it that way. It avoids change. I enjoyed this book but it remains, for me, a fine piece of biography of its time, not even attempting to advance the ways we ought to do biography.

That’s enough though I think. Do read this elegant book? Just remember its partiality.

Bye for now

Love Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Peter Jefferies & Gregory Jusdanis (2025: xv) Alexandrian Sphinx: The Hidden Life of Constantine Cavafy. London, Summit Books, Simon & Schuster as cited in https://livesteven.com/2025/12/20/it-was-this-blog-of-course-it-is-on-peter-jefferies-gregory-jusdanis-alexandrian-sphinx-the-hidden-life-of-constantine-cavafy/

[2] Michael Londra (2025) ‘Book Review: Alexandria’s Sphinx: ‘Constantine Cavafy: A New Biography’ (the USA book title) in The Arts Fuse – online (August 26, 2025) Available at: https://artsfuse.org/315709/book-review-alexandrias-sphinx-constantine-cavafy-a-new-biography/ citing Peter Jefferies & Gregory Jusdanis (2025: xv) Alexandrian Sphinx: The Hidden Life of Constantine Cavafy. London, Summit Books, Simon & Schuster. This quotation can be found im my blog at:https://livesteven.com/2025/12/20/it-was-this-blog-of-course-it-is-on-peter-jefferies-gregory-jusdanis-alexandrian-sphinx-the-hidden-life-of-constantine-cavafy/

[3] James Campbell (1991: unnumbered) Talking at the Gates: A Life of James Baldwin, London, Faber & Faber.

[4] ScottManleyHadley (2024) Talking At The Gates: A Life of James Baldwin by James Campbell – Triumph Of The Now blog (March !1, 2024) Available in full at: https://triumphofthenow.com/2024/03/11/talking-at-the-gates-a-life-of-james-baldwin-by-james-campbell/

[5] James Campbell 1991, op.cit: 261.

[6] Douglas Field & Justin A. Joyce (2021:167 & 169) ‘How Long Blues: An Interview with James Campbell’ in James Baldwin Review DOI: https://doi.org/10.7227/JBR.7.10 Number: Volume 7: Issue 1, 167 – 183

[7] Ibid: 179

[8] Ibid: 181

[9] Cited ibid: 182

[10] Ibid: 183

[11] Ibid: 173

[12] Ibid: 174

[13] Ibid: 176

[14] Ibid: 170

[15] Ibid: 173

One thought on “Despite the literary establishment, biography can be done differently. Reflections on James Campbell (1991) ‘Talking at the Gates: A Life of James Baldwin’.”