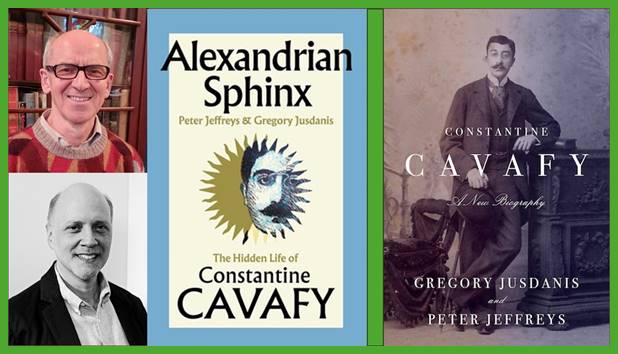

It was this blog, of course! How to write on a life, whose archival raw material is ‘marked by two conspicuous gaps – the relative absence of material regarding Constantine’s erotic life and his views of Muslim Egyptians’.[1] This is a blog on Peter Jefferies & Gregory Jusdanis Alexandrian Sphinx: The Hidden Life of Constantine Cavafy. London, Summit Books, Simon & Schuster, 531 pp, £30

Most lives contain ‘gaps’ in the eye of looking at them from outside and hence the role of the biographer could be seen as finding a way of telling the life story of someone in a manner that, in one way or another fills the gaps in the archival or gathered oral interview material with at least an idea of how the knowledge we do have fits together in an integrated way. Perhaps however the activity in most poet’s lives is hard to see because internal, and where external only consists of sitting in a chosen space constantly revising the words that might allow some experience to expand and collect meanings and associations in the way the language of its expression resonates in the mind and body of a reader. This idea is put well and simply by Michael Londra in an Arts Fuse review of this biography of Cavafy in its rather different looking (even in the sequencing of the author’s names and book title) American edition.

Whenever confronted with “perfection of the life or the work” (as W.B. Yeats characterized it in “The Choice”), the latter wins out. As a result, any writer’s “real life” will be at a desk, rewriting the same sentence a thousand times—not scintillating fodder for biographers.

However it is not just this fact of any poet’s life that reduces the material that might fleshes out a biography of interest to anyone other than another poet interested in the process of writing poetry itself. Londra goes on to show that the new biographers of Cavafy have the temerity to turn a problem in the writing of biography into a critique of biography as genre of writing, and Londra does not like that (as he does not seem either to like collaboration by two writers as a mode of writing that ought, he seems to suggest implicitly, be done by one person from one perspective on the life)– pointing to the Authors pretensions to be writing biography differently (that he thinks it pretentious being apparent in his choice of stereotypical trope to characterise their work as opting ‘to reinvent the wheel’).

But, as Jusdanis and Jeffreys acknowledge, “this is one of the paradoxes of the Cavafy phenomenon: one of the most celebrated poets of the twentieth century, the most frequently translated Greek poet into English, has had few biographies,” most likely because of a “lack of interest” on the part of would-be chroniclers deterred by “the predictability…of the poet’s life itself.”

Indeed, the “facts of Constantine’s life are…unremarkable and very straightforward.” That said, Jusdanis and Jeffreys encountered other difficulties: the “physical absence of evidence, the gaps in his records, and our own discomfort with traditional narratives of life stories.” For these reasons, the authors opted to reinvent the wheel: “we decided not to follow a standard ‘birth-to-death’ chronological direction…[telling] a circular narrative through various thematic sequences.” This enabled them “to draw attention to the artificiality of biography as a type of writing.” [2]

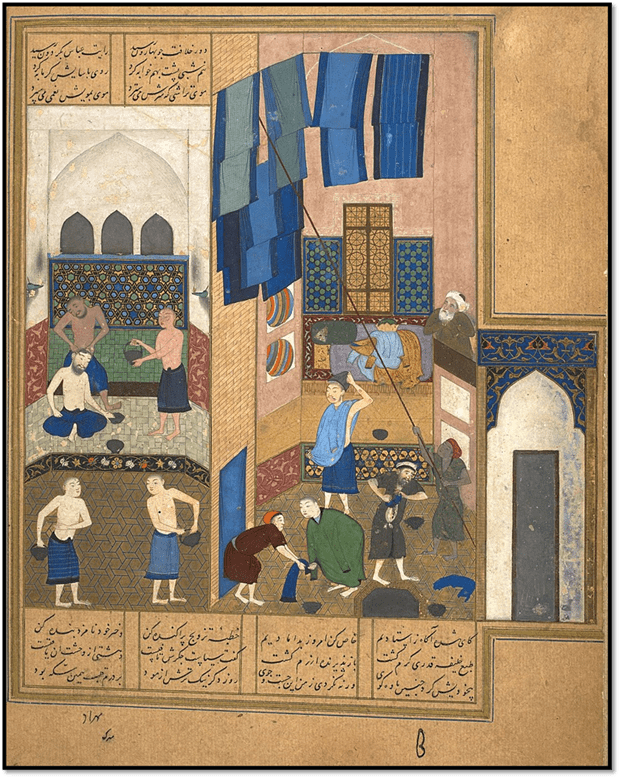

Other biographers manage to use this ‘artificiality’ to raise biography to the level of self-conscious art Londra argues citing work in his own field, and perhaps implying too his own method as a biographical essayist on Delmore Schwartz and others. I think however, Londra is perhaps over-keen to push his ow favoured view of what biography can be to take into account the strengths in Jusdanis and Jeffreys’ method, which Unlike his respects the gaps in the record of Cavafy’s arrival remnants to pretend they don’t matter and can be filled by the single biographer’s interpretive take on the poet. In my title I pick out the authors’ reference to two ‘conspicuous’ gaps – that deal with any record of those elements of his verse that broke boundaries in the transition of Cavafy from a man steeped in Victorian Romanticism and showing it in the erotics of an idealisation of young male beauty to one who began to honour the lacunae that sometimes stops the growth of a mature queer male poetry – the practicalities of sexual congress between men through the gaps in the veil of complex and fragmented ‘heteronormative’ societies such as that of colonial Egypt which its tradition of the hammam (see my blogs on the erotics of bathing at this link and this on gay bathhouses), and the related subject of the play of desire across class and, more significantly (but linked) racial difference.

Londra does not I think really take on board either of what the author calls the ‘most conspicuous’ gaps for he does not see their significance to the writing of global queer lives, and, by the way, very much simplifies the implications of the author’s method of confronting the difficulties of Cavafy position in the gaps between constructed divisions (to the level of formal apartheid in some respects) of class and race in Alexandria, that Cavafy was acquainted with both as person who inhabits the margins these divisions create as a single queer man and as a man whose experience of the class and race system was compromised by the effects of relative, if ‘genteel’, poverty on a foreign national’s civil service wage from the British occupation of Egypt. Londra rather admires the picture of Cavafy seen as floating upon the surface of these divisions, expressing it thus:

Jusdanis and Jeffreys don’t pull punches regarding the impact of colonialism on Cavafy: “the modest life he enjoyed in Alexandria as a civil servant depended on British hegemony in Egypt.” Colonialism did not bother him. He “was a liberal humanist, more sexually than politically progressive.” And while “Alexandria was…a Muslim city,” Cavafy’s “commanding knowledge of historical change…did not provide him with insights into the social transformation taking place…the Egyptian nationalism spreading” around him. Revolution was in the air. He was oblivious. Narcissistic (like many other poets), “Constantine was most happy…and true to himself in the Alexandria of his creation”—a decadent, decaying city of concealed desires and crumbling cosmopolitan façades whose wealth was guaranteed by the relentless oppression of the indigenous population.1

If I thought this biography really validated Londra’s assertion that Cavafy was merely ‘narcissistic (like many other poets)’ then I would have great reservations about it, but what Londra misses is that this biography uses a method that can capture the fact that these things were true of Cavafy whilst also being, in other contexts (and reflected in the later poetry), untrue – for those poems are not merely narcissistic and move to imagine the interior of bodies and minds that Londra thinks the authors have made invisible to Cavafy – queer men and desire that can cross ‘racialised’ boundaries. That they are invisible is more, I would say, because of the gaps that biography often covers up, where contradictory experience, with more multiple facets than any summary on the poet’s response to colonialism, and especially British colonialism, can cover.

When Londra summarises his view in his article’s headline, he says: ‘Unable to place the life and work of Constantine Cavafy in a holistic context, the biography can’t sustain momentum. Key points remain scattered, unintegrated’. But this is very simplistic. I do not see the books authors as blinkered and incapable but the reverse. Holistic contexts are often sources of overinterpretation applied by biographers. This these authors want to avoid. The point about biography is not that it should have the momentum of ‘what-happens-next’ page-turner but that it shows the contradictions in which all lives are lived by examining each scattered aspect of those lives separately – repeating the life-cycle differently in the light of this aspect many times. Hence, what emerges is the sense of a life much larger than its parts, able to live too in its otherwise unseen gaps, whilst showing how those gaps keep getting hidden by mainstream perspectives.

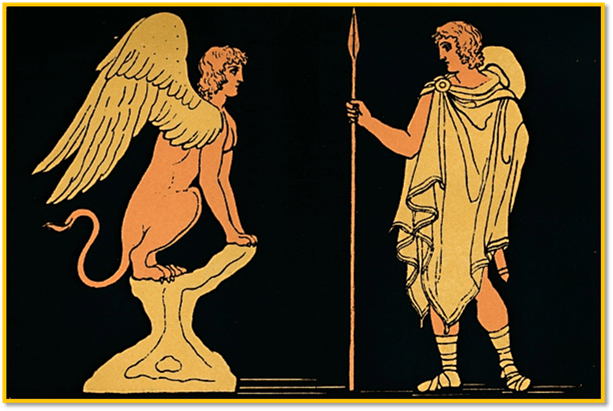

The hermaphroditic Sphinx too ensures that the solution to their riddles involved people bringing together apparently unrelated facets of one life that never quite add up into one thing. No doubt that is why Oedipus was so good at solving their riddles, for he never quite expected his life to have coherence – and he was even more surprised to find it had even less coherence than he thought. And this is how Cavafy strikes me in this glorious book.

It is surely time for me to say why this book is a real asset to lovers to Cavafy’s poetry. I have written before about the poet – once reflecting on puzzles in translation of the poet (at this link) and once on one poem where the young men of Cavafy’s fascinated hold in absence become gaps between movable furniture items (at this link), a poem discussed too in this biography.[3] But this new biography also opens out so much more of the poet – in my view mainly because of his inventive play with the genre of biography, allows us to love his gaps, just as he did, including his transnational and transracial Hellenism (for, especially after 1911, he insisted he was cosmopolitan Hellene – preferring Hellenic Greece even to that of Byzantine Greece, and hence – not a Greek per se, and an Egyptian first and foremost), even whilst he wrote primarily in Greek – though a Greek that was critical of some of the conventions of that language when over-simply understood as either katharevousa or demotic.

The real value of this biography relate in part at least to its formal structure. That structure is based on its authors suspicions that the normative biographical form, which tells a linear story based on chronology, and must (in order to cohere – which is its imposed requirement) tell of a singularly straight line of development. These authors are convinced that lives when seen in the eye of reflection, as they must be, do not look like this. In fact, they show that if we select certain themes and trace them separately across the life-course then we get a slight difference of emphasis on the life’s meaning, which matches the fact that life themes are multiple and often contradict each other in the playing out. Told in this way, we cycle through the life over and over and find not only differences in meaning in contradiction and / or interaction but also see that gaps exist in lives that aren’t usually so evident in conventional biography, but which matter in relation to the works performed in that person’s life – in Cavafy’s case works of poetic art. It is in this new form that we see that certain themes in the lifework of an artist that live in gaps between the acted and unacted, the said and unsaid, the recorded and unrecorded, the continuous and discontinuous, and (perhaps mainly) the apparent and the actual.

Londra is, as we have seen implicitly antagonistic to such innovation. It shows in his characterisation of the biographers’ method of telling the story. They describe the form of the book as necessitated not by insight into how to tell the stories which are significant but not necessarily parts of a singular whole in Cavafy’s life as if the authors were somehow deficient in critical intelligence, or ‘guts’ or some other masculine attribute that makes them ‘unfit’ for their Herculean labours, using rather sarcastically derived diminutives (for instance, ‘bite-size morsels’) to reduce the significance of what is achieve or the intelligence that conceives or is intended to receive it:

Overwhelmed by the magnitude of their project, the authors’ self-confessed “discomfort” with biographical narrative feels more like an admission of defeat. Partitioned into five sections—with an “interlude” on “Constantine’s Reading” between parts three and four—the book’s structure is reminiscent of a collection of essays. Unable to place Cavafy in a holistic context, momentum is never sustained. Key points remain scattered, unintegrated. Priorities are irregularly emphasized. ….

……

Breaking Cavafy into bite-sized morsels, Jusdanis and Jeffreys divvy the volume up into “The Cavafy Family,” “Alexandria: The Dreamscape,” “Friends,” “Living for Poetry,” finishing with “Cultivating Fame.” This “sensible-shoes” strategy ends up walking around its subject, afraid of walking up to him. Each chapter contains further subsections. Presumably these represent the authors’ individual labors, though there is no attribution to indicate who wrote what. There are repetitions—likely the outcome of two minds separately plowing the same biographical ground.1

But let me take that ‘“interlude” on “Constantine’s Reading” between parts three and four’. Yes. This section might jar and break the flow of the life but it does so for a reason by emphasising first, its least achievement, the kind of reading accomplished, and its written critical sequelae of ‘readings’ of the poets and others(Ruskin for instance) read. The section on the readings of Tennyson and Browning, for instance, show him already working to achieve, by later reflection, a new style that learns by critical intelligence and reding skill.[4] For instance without that information (impossible to make part of a flowing story of unitary development – for who care about what other poets, later poets merely ‘read’), we will only half realise how wonderful was Cavafy’s reinterpretation of the story of Saint Simeon Stylites, from the area of Cavafy’s own interest in the Hellenistic Empire, as it birthed the Byzantine one. The later poets take on the saint was deliberately displaced from the commanding view of Greek Christianity to the eyes of someone ‘not a Christian’, and is Syrian, speaking from within Arabic wisdoms. In fact, if we know our Browning it is similar to Browning’s attempt to write of the Lazarus story from the perspective of an Arab physician (in An Epistle Containing the Strange Medical Experience of Karshish, the Arab Physician), an method that tries to derive meaning as an derived from the gap between belief systems considered incompatible and contradictory. That is the story that the book tells about the poetic work and the strangely conventional and apparently limited man that was their poet or maker: ‘Could poetry. An apparently impractical pastime, hold its own against the absolute devotion of this saint?’.[5]

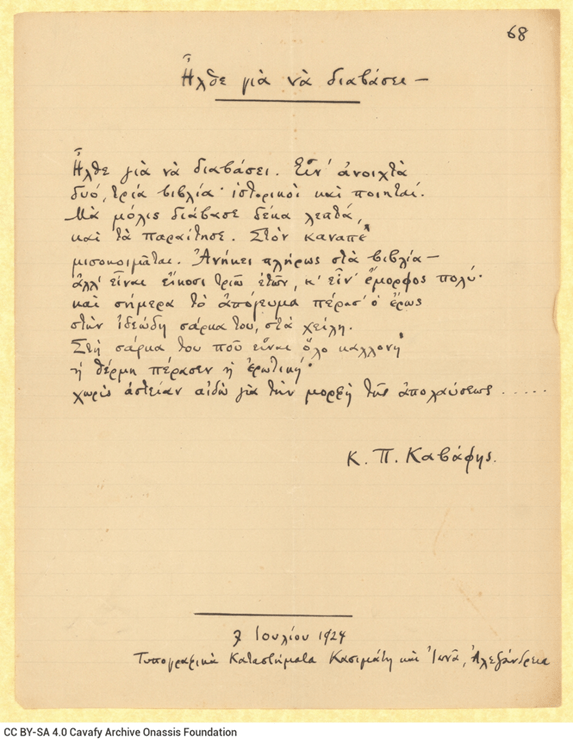

But the main reason for the interlude, intervening between stories of the kind of known social landscape of his admissible friends and the section which tells the story of the vast changes in Cavafy’s practice with poetry in 1911, when he is forty, and its relation to artistic vision changes in a revolutionary way – one that began to search Alexandria outside its hegemonic European cultural stranglehold in his friends-of-one-privileged-class-derived perspective, is that we need to be shown that ‘reading’ is a very much more involved activity than we though, one that relates to bodily relationship, contact skin to skin, where that boundary has multiple forms and colours. The self-justification for the chapter’s inclusion of a survey of Cavafy’s ready comes from a poem (see one of the original Cavafy broadsheets in Greek below) translated as He Came To Read.

He came to read. Two or three books

are open; historians and poets.

But he only read for ten minutes,

and gave them up. He is dozing

on the sofa. He is fully devoted to books

but he is twenty-three years old, and he's very handsome;

and this afternoon love passed

through his ideal flesh, his lips.

Through his flesh which is full of beauty

the heat of love passed;

without any silly shame for the form of the enjoyment.....

The translation the authors use better captures the sensuality of the poem which turns from a very dry notion of reading to on that is incarnated in the beauty of the reader’s self-consciously ‘perfect’ body becomes penetrated (the authors’ translation insists on this) the surfaces of skin, showing the kind of ‘enjoyment’ true reading of true poetry might yield.[6] Nowhere do the writers enforce my reding here – the keep the chapter dry and hard – but they do when they eventually come to characterise how Cavafy revolutionised how poetry is read such that it takes on the internal sense of the reader’s awareness that the body of beautiful verse is akin to their own youthful body and its own sensuality, or to the memory of that body in older men, as:

Their healthy, sensual minds, Their firm flesh Are stirred by his notions of beauty.[7]

Constantine Cavafy in 1929. Photo: C.P. Cavafy Archives – Onassis Foundation

Perhaps though, the beauty of the book is that it detects and uses the ‘two conspicuous gaps – the relative absence of material regarding Constantine’s erotic life and his views of Muslim Egyptians’, as the rationale of its renewal of our vision of Cavafy below the surface of the dry scholastic mask he oft donned, this despite the fact that he was an auto-didact and not formally educated in academic institutions.[8] Let’s take both gaps together for their messages conjoin:

- the relative absence of material regarding Constantine’s erotic life

- his views of Muslim Egyptians.

In a book that ends with a death – that of the subject of the book, we cannot I suppose wait to get to those parts of the biography which flesh out the embodied erotic life that speaks from our knowledge of the poems. In order to accommodate our sense of this absence, the book continually slips the absence of such material in media res. The book starts with the story of Cavafy’s biological family in Part I, but instead of moving from there to a treatment of his known circle of friends (which is in Part III), it slips between these ‘Parts’ of the book, a Part II called ‘Alexandria Dreamscape’. This has two sub-sections (chapter 4, Constantine’s World & chapter 5: A Tale of Two Cities). The titles tell us a lot. In Alexandria, there were two cities, a Colonial and Judaeo-Christian one, with a large Europeanised Greek contingent, and other – its lesser shadow in texts of Western literature but containing the majority of its residents, a Muslim one.

The division of these cities is fundamental to both gaps. Most accounts of Cavafy extend the radius of his activity within the first of Alexandria’s cities – although perhaps less so in similar split in Istanbul both the ‘lost capital’ of Constantinople to Cavafy and the extended Muslim city based from Stamboul, for most suspect Cavafy first had sex with men in Istanbul, though little is recorded, as it would not be. Yet these beautiful chapter, especially that of the ‘Two Cities’ show us that though unrecorded Cavafy must have much to do with a city that flew under the radar of the Orthodox Greek community, but which emerge in the discreet lack of naming of specifics of the poetry, such as the brothel in the Muslim city where, when Cavafy was ‘very young’, ‘Eros with his extraordinary power / had taken hold of my body’. The authors make it clear without forcing the point (for there is no ‘evidence’ which biographers require, that this house, ‘a bazaar of love’ would lie in the Muslim areas of Alexandria, just as the hammams did where same-sex sexual congress was tolerated as long as kept from the notice of the religious authorities.[9] We only know that Cavafy, living in a working class neighbourhood must have constantly passed through the areas in which these opportunities resided and been involved in situations where some activity was deracinated.[10]

Hence, though we know that the Greek community treated Muslims and the Egyptian fellahin – called arapides or Blacks by them – as a ‘separate race’ between whom contact must be limited.[11] Yet we know Cavafy frequented the Café Al Salam, searching for a young man we only know as Totos, and that his past friend Timos Malanos referred in his scurrilous book on the poet to the activity of Cavafy there as reprehensible, it was not known for sure and contested by friends and European literati who wanted to evade any stain on his reputation – he was known to be ‘homosexual’ but not ‘promiscuously, as inter-racial sex evidence would have cemented.

Moreover, the biography shows that though Cavafy was a dependent employee of the British Imperial rule at Alexandria, he was capable of manifesting anti-British sentiment, if only subtly in poetry and alongside his self-presentation as a Victorian Anglo-Greek gentleman. One of my favourite sections is on the Denshawai Affair in which the British used Arab young men as scapegoats for their failure to quell the civil unrest their policies ensured. We see him take on a poetic identity which while openly anti British conventions in its sexualisation of the young Arb male victims of British injustice – the hung a number of young men without evidence, he also diverts even from this refusal of convention to sympathise with the mothers of the murdered young Muslim Egyptians, describing them as ‘martyrs’.

The innocent boy of seventeen years Who dangled pitifully in the empty space, In the seizures of his dark anguish His adolescent body, handsomely formed, His mother, the martyr was rolling in the dust.[12]

Likewise, though Cavafy is described as quite unknowing of the aims of the Muslim Brotherhood, formed at that time, he also was friendly to seeing the open congress of Arab-Egyptian and Hellenic Greek-Egyptian as a meeting of the ‘children of Egypt”.[13]

However, though the poetry supposes the gaps in the account, it gives no ‘signposts’, as the biographers describe them, to the possible worlds of erotic life and knowledge of a world outside the conventions of the Anglo-Greek enclave and of knowledge of Muslim young men, who asked outright about whether a Greek should partner, he says cagily, ‘It should not happen’. Yet I think this biography opens the doors on the unsaid because it refuses the singular narrative line and authoritative control of the life as if it were one theme. For me, it is a very good biography. I love it, for Cavafy went some way to defying homophobia in his own time, but it is clear that whether he went further than some way, remains in the unspoken, unrecorded, unthinkable (to some) gaps.

Do read the book!

With love

Steven XXXXXXXXXXXXXX

[1] Peter Jefferies & Gregory Jusdanis (2025: xv) Alexandrian Sphinx: The Hidden Life of Constantine Cavafy. London, Summit Books, Simon & Schuster

[2] Michael Londra (2025) ‘Book Review: Alexandria’s Sphinx: ‘Constantine Cavafy: A New Biography’ (the USA book title) in The Arts Fuse – online (August 26, 2025) Available at: https://artsfuse.org/315709/book-review-alexandrias-sphinx-constantine-cavafy-a-new-biography/

[3] Peter Jefferies & Gregory Jusdanis, op.cit: 303f.

[4] Ibid: 257f.

[5] Ibid: 321f.

[6] Ibid: 249f.

[7] Cited ibid: 415

[8] ibid: xv

[9] See ibid: 173

[10] Ibid: 118 – 123, for the use of hammams for sex see ibid: 62

[11] Ibid: 145f.

[12] Cited ibid: 161f.

[13] Ibid: 165

3 thoughts on “It was this blog, of course! It is on Peter Jefferies & Gregory Jusdanis ‘Alexandrian Sphinx: The Hidden Life of Constantine Cavafy’.”