‘For a long time, the mother thought life-changing moments were momentous. Entirely unambiguous’.[1] This beautiful, moving and comic line from Bryan Washington’s Palaver rhymes with one of his chosen epigrams for the novel by Akira the Hustler (ハスラーアキラ, Hasurā Akira) : ‘Our days are demarcated in the repetition of little goodbyes’. Prompt questions are so encouraging of over-simplistic thinking that the use of terms like ‘one’ and ‘self’ as if they named straightforward and unchallengeable constants. This blog is a reflection of Bryan Washington (2025) Palaver New York, Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

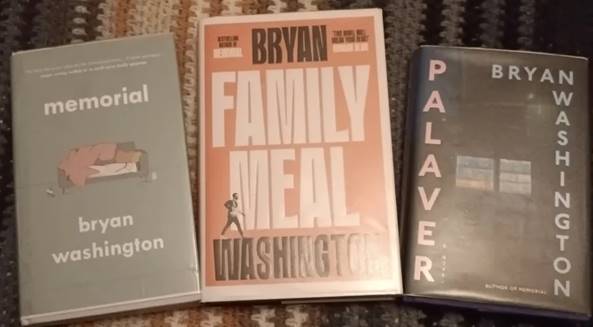

Palaver is not only Bryan Washington’s latest novel, it is his best in my opinion (and also in that of most of the available reviews in the USA), somehow doing, apparently naturally and without palaver (I mean just technical ‘palaver’ and not enough to detract from their high quality of crafting, even technically speaking), what is done more fussily and mechanically in his otherwise fine novels Memorial and Family Meal (for my blog on the latter use this link). Reviewers are correct to pick up on the novelist’s controlled and brilliant use of dialogue and third-person narration (with very pointed use of the character’s distinct points of view).

This is a feature of which Washington was very particular and he expands upon it in an interview (it’s an edited one so we can’t be sure of its total validity and reliability) with Stuart Miller in The Los Angeles Daily News. Miller points out that, though he never names the characters he calls ‘the son’ and ‘the mother’ respectively, he does allow that the book ‘shifts perspectives from the son to the mother’. Miller wonders whether this technical aspect of the novel was ‘something that’ Washington ‘set out to do’, since ‘the reader may shift sympathies as it happen’. Washington replies by referring to the craft tradition of art, to the ‘works that I’m really taken by’, wherein he doesn’t ‘feel the heavy hand of the author, of the filmmaker, or the musician’. His elaboration of this idea is telling, because he does not equate the freedom that a novelist allows in characterisation as merely a matter of showing their perspective on things and negating the omniscient author’s overall control but a compromise with that control over plot and characterisation:

So I may guide the narrative one way or another, but it’s ideal for me if a reader is able to find their own sense of what happened, and why it happened, who these characters are, and where they ended up with minimal interference from me. The catch being, of course, that I’m molding (sic.) all of this.[2] (my italics – SDB)

Miller’s interview is generously motivated. He allows Washington to explain why he gave voice to those who generate active homophobia, verbally (in the case of Chris, ‘the son’s brother’ or physically in the case of ‘the mother’, ‘The son’s’ mother). Washington, in his reexplanation makes it clear that such demonstrations of a possibly pernicious point of view, a homophobic one, in a character is necessary, for his ‘moulding’ of his story and characters is not aimed at positive images of queer life but to show the complex process of change in ‘people as they work toward coming together’. I find this innovative, for the novelist shows less concern with the condemnation or redemption of individual character but in how social groups (even simple dyads – like mothers and sons) are formed, maintained, lapse into fragments and then reform even more strongly) grow unevenly – and with lapse – into coherence and group identity (the role I think of the choric group of queer people in what is called either ‘Alan’s place’ or its names as a LGBTQI+ venue, FRIENDLY).Put like that the idea seems clunkily obvious, but, trust me, it does not fell like that on reading.

And Washington goes on to link all this to the technical achievement of the novel and the advantages of third-person omniscient narration:

I was at least astute enough to realize at the beginning that the first person wouldn’t be compatible with what I wanted to do. … / What was interesting to me was whether or not reconciliation is possible with a person after challenging experiences, and what it can look like to relearn someone or to navigate and find a middle ground for how to know someone that you thought that you knew. What concessions does someone make? What is not acceptable? And how does that impact the relationship insofar as there can be one going forward?. / So I had to find the third person and distance from that to approach those questions in a way that made sense.2

I wish to quote so heavily from Miller, for – in so short a piece – I see more pertinent literary, emotional and moral intelligence about the relationship of the form and technique of art with its thematic and ethical goals than I have ever seen in journalism, especially UK journalism. Miller notes that, in the past, Washington has claimed not to be ‘a particularly optimistic person’. He contrasts that fact, without querying it, with another relating to this novel in a particularly acute critical perception that ‘his characters move from isolation to engagement and community’. Washington replies:

It was a conscious decision. I write towards optimism, knowing that it is not something that comes particularly naturally to me, so it is very much like a “Fake it till you make it” thing. If I continue to at least attempt to walk the path of optimism, then I’ll look up and I’ll be on this trail, regardless of whether or not I feel I should be there.2

And the specific ‘optimism’ that is faked, is one about the growth of community and a kind of cognitive-affective communalism, of the sort my blogs always revolve around promoting as a belief, if only in myself (for I have no illusions of them being read widely). And I cannot move onto my theme in this blog – the representation of the occurrence of life-changes in individual people, or groups of such people (from dyads upwards – ‘’couples’ if you like, for much of this novel is about coupling (even in heterosexuals who once owned the term ‘couple’), decoupling and group transformation. To do this I this I will point to another review that picks up a feeling that permeates the novel for me too – its sense of how communities interact and inter-communicate, Alesis Burling’s review in The Washington Post:

Of note are the long walks the mother takes around Tokyo, slowly acclimating herself to its curiosities and charms. Washington’s descriptions (and evocative photographs) of the frenetic, pulsating metropolis — the maze of train lines zigzagging across the city; the unmarked bars and dimly lit noodle shops stacked on top of each other, serving “fish poached in dashi under handfuls of herbs” and “matsutake mushrooms simmered in sake”; the brightly lit 7-Elevens around every corner — are so infused with quiet beauty and anonymity and the bustle of life that it’s easy to feel as if we’ve been dropped right into the middle of the fray.[3]

This only seems like a thin description of the novel, but (trust me again) it isn’t – it is packed with the strengths of Washington’s mature writing. Long walks and travel commitments are posed throughout as ‘adventures’, risking the unknown and particularly the risk of being lost in the latter – in streets without a map or direction signs or hints from the type of signs around you. [4] Some adventures in the book are merely photographs without caption, others attend upon things like ‘the mother’, for instance making ‘a point to venture further everyday’ in order to tame the unknown (to Japan from Houston or wandering the streets at Tokyo in new circumstances), face whatever danger is purported to lay there, or even being sent on an errand where you ‘don’t know where any of that is’ (and nevertheless, as Tej does, saying ‘I love adventures’).[5]

The novel is structured around points of choosing to leave or stay (with a familiar place or relationship type such as heterosexual marriage, or sex/gender identity), departures and arrivals (another meaning of adventure). It balances the need to venture out in risk (adventure indeed) with the commitment to ‘take care’ of self or other (or tending to someone or something – even a bar by a bartender) and what that means, to feed the other lovingly – such as deer in a park when you are literally lost or when soothing the traumatised kitten Taro) to the classic ideas of ‘taking care’ applied to the expected roles of a mother (or a son to a mother).[6] But discourse of ‘caring’ are also used and stretched in meaning when the mother and the son discuss why one should ‘care’ to ‘care’ for a cat or not.[7] The most adventurous form of being fed and taken care of is in the story of the hummingbird residing and feeding off the teeth of a crocodile.[8] As Alan learns for himself and his clientele ‘taking care’ of his bar is a wide responsibility to the queer family assembled there, and to himself, seeking support in his adventure into sex/gender transition. And all that resolves into a supposed concomitant, something we have to reconcile with an opposed desire to merely take risks by venturing into the unknown:

You’re my child. And I’m your mother. I’m supposed to take care of you./… / … maybe we should be taking care of each other. And I don’t, you know, think either of us has been doing a very good job of that.[9]

People move away, or remember moving away from the familiar, sometimes to the point where it seems nothing will be familiar – or ‘canny’ – but always to be relearned. The mother leaves Jamaica, Texas, Houston, Cheryl leaves those places to, and her lover – to be taken up by the mother – and eventually her sexual identity to be happily in lesbian adventure, guided by the mother, people learn new locales in a city – even one they know. Ben leaves wife and child but must relearn and Taku wonders how much sexual loyalty need mean in relationships, with or without a child to consider. Always the difference we face is based on whether we have a ‘guide’ or a ‘map’ to recognise things we otherwise would not and describe as being lost: the book opens thus; ‘The mother was lost’, people can get lost and disorientated even in a department store or in the gay scene of Tokyo when it is unknown to you.[10]

The reason we stay, and the reason we move away is to find the nearest equivalent place, space and company to call ‘home, but the feel can be graduated. Whilst the mother muses that , born on an island like Jamaica, ‘means you you’ll always find yourself being called back’, her son, ‘the son’, is forever looking to be ‘ where I fit best. And where I’m most comfortable’. It is turning out to be Tokyo but he had to leave Houston ‘to see it’.[11] Nevertheless, earlier on in his sojourn, the son ‘hadn’t decided whether the city was truly home or not’.[12] Later we are told, but again in a flashback to earlier in his stay that the son ‘circled around the idea of returning home’, where that home was Houston.[13] It is an invitation to that former home his mother towards the end of the novel poses but by then what she calls ‘home’ is a ‘strange place with strangers. And I won’t do that’. He is, he says, in Tokyo ; ‘I am home’[14]

For some the idea of what is ‘home’ is contingent (for Taku who decides on his sexual preference and for either polyamory or monogamy it is based on the contingency of the birth of a child to his equally sexually fluid wife), or for Meiko, the receptionist at the hotel at the Nara deer park, who says of Nara when asked why she stays there by the mother says: ‘I don’t know if it’s that I wanted to stay, … But this is the first place I haven’t tried to leave’.[15] It is a statement that resonates, for totally different reasons, in he experience of the son, the mother and plentiful other characters, whether that ‘home’ is a place, a body, a biological or chosen family group, even that constituted by FRIENDLY, the bar that is ‘Alan’s place’, for ‘his relationships at the bar allowed the son to settle in. Tokyo became a little less lonely’.[16]

The issue that straddles and unites the supposed binaries of staying or leaving, settling in or adventuring all is that of life-change, and is this reason why, in my title, I yoke the epigram from a rent-boy become poet, Akira, with their idea that life is repeated ‘little goodbyes’ with the mother’s reflections on whether and how she too has changing, and is changing more in her stay with the son in Tokyo – the issue is ‘life-transition’. For Alan ‘life transition’ is taking a leap forward with ‘top surgery’, for Ben in leaving a wife and son he no longer loves together with his attendant psychosexual choice, for the Japanese ‘old men’ on the sale of the izakaya they once attended so that it can become a Thai restaurant owned by three women, a place where the mother slowly confronts changes in herself too in conversation with Ben. ‘What happened to the old me’, the mother asks:

They kept coming for a while. But as the crowd changed, the restaurant’s ambiance did too. I don’t think it felt like it belonged to them anymore. Eventually they stopped showing up.[17]

The mother finds that ‘a sad story’ but for Ben ‘it’s sweet too. That’s life, if we’re lucky’. I suppose it’s a lucky event because the life transition just happens without overt or visible pain, but only because we are never invited to the perspective of the old men themselves. But there is a lesson here. Perhaps the process of life transition, if we’re lucky is not always attended by surgery, as it is with Alan, memories of violent trauma as for the son remembering his mother’s past violence and his brother’s homophobia, but just, sort of, appears to happen naturally. That is the beauty of the sentence in my title, which comes from the mother’s reflections from her home in Houston on the unprepared adventure to move away to Toronto with Cheryl and Earl. It all changes, as if by itself, as if like the action of the tidal waves lapping on sand, but also promising something of the lesbia future of Cheryl with the mother as her friend. The imagery is full of ambiguities about leaving as staying, settling as adventuring:

The mother focused on the water. Waves lapped at the shore. Cheryl settled beside her, laying her head on the sand, wiggling until their ears brushed. It was entirely too hot, but the mother didn’t mind. She wanted it to leave an imprint on the island. She never wanted to forget how this felt.

For a long time, the mother thought life-changing moments were momentous. Entirely unambiguous.’[18]

However, of course moments are not by definition ‘momentous’ (the jingle in the words makes this sentence almost tragi-comic. Moments are ambiguous transitions not always going off in the direction you expect, or think you desire but happening because they must because of some internal, external or mixed contingency – and which contingencies are not both internal and external to the person undergoing transition. Strangely enough, as often in this novel, the concept of life-change and prompts to them are brought up in an ironic, perhaps sarcastic, tone. The son says, rather bitterly: ‘I’m struggling to see what life change brought you all the way to fucking Japan, after all this time’.[19] But sometimes it is done beautifully. Silent refection on memories – even memories of past dialogue – can be part of ongoing change as Ben says to the mother, summarising their evening together:

After tonight, it’ll fade into the air. It’ll be just something that happened. But we’ll both walk around with it, in our minds. It’ll be something that lives with us. And changed us.[20]

I think I could write forever about the delicacy of the writing itself, though many reviewers say that this best shown in the Washington ability to handle dialogue, often in a way that does not seem to want to communicate, in the case of differences between persons, or does not need to because of commonalities in a group. The balance of speech and silence is often invoked for this reason, or decisions to stop or restart communication, as between the son and brother Chris – as perhaps the mother and her brother Stefan. Again, it is sometime subtly joked about, as when the mother sums up her stay in Japan with him and he misunderstands her reference in ‘I think what I’ll miss is the silence’.20

The novel is called ‘palaver’, often meaning an unnecessary fuss about things in modern uses but derived from metalanguage (talk about talk):

Palaver (n.) : 1733 (implied in palavering), “a long talk, a conference, a tedious discussion,” sailors’ slang, from Portuguese palavra “word, speech, talk,” from a metathesis of Late Latin parabola “speech, discourse,” from Latin parabola “comparison” (see parable). A doublet of parole.

In West Africa the Portuguese word became a traders’ term for “negotiating with the natives,” and apparently English picked up the word there. (The Spanish cognate, palabra, appears 16c.-17c. in Spanish phrases used in English.) The meaning “idle profuse talk” is recorded by 1748. The verb, “indulge in palaver,” is by 1733, from the noun.

There are various kinds of palaver in the novel, but often it denotes exchanges in multiple languages, which all the participants of the talk fail to share, that even includes place names for some characters (and readers). The son teaches English to South East Asians across different language differences. The mother notices that attitudes to her may differ when she is with her Japanese speaking son.[21] Context changes language forms, such as in writing poetry, like the mother’s secreted texts, or the language in cell-phone texts. Sometimes subcultures talk entirely in different discourses, and sometimes language is fractured by mental disturbance, such as in those moments in which the son finds himself ‘forgetting his words’, in all kinds of interaction.[22] And there is another language context in the novel – that of its uncaptioned photographs. Some commentators believe this fixes the location in the novel – add, as it were, detail, but to me they are ambivalent, bruiting that their meaning shifts in relation to your knowledge and recognition of them, from the experience of being lost to the experience of familiarity and experiences in between these. They are of places in which duration of stay itself changes – flats with laundry, shopfronts, the concourses of train stations and can be of different time frames – night, evening, morning, midday. They contain human figures sometimes, sometimes not. They are ambiguous. They tell us little of what goes in on them, like the evening before the son saves his mother’s life in a possible traffic incident. The human environment is indifferent to it all, after a raging argument between them:

It was, despite everything, a beautiful evening

She would remember the air. And the light. The way the chill calmed her face.[23]

In truth, I feel very dissatisfied with my commentary here. The book is greater than anything that can be said about it. I can’t wait to get my books signed by this great author and queer hero-philosopher on the 22nd January (see the blog on that at this link).

But note, the book is an answer about what is the ‘one thing’ to change about myself, It is remember that that the moment of change is not momentous: it is life itself ,together with all of the moments before and after it.

With love

Steven

[1] Bryan Washington (2025: 130) Palaver New York, Farrar, Straus & Giroux

[2] Stuart Miller (2025) ‘How Bryan Washington spent years finding a new way to write Palaver’ in Los Angeles Daily News (online) available at November 25, 2025 at 12:18 PM PST: https://www.dailynews.com/2025/11/25/how-bryan-washington-spent-years-finding-a-new-way-to-write-palaver/

[3] Alexis Burling (2025) ‘A National Book Award finalist lands readers in the frenetic heart of Tokyo’ in The Washington Post (November 4, 2025)

[4] Bryan Washington op.cit: 13

[5] ibid: 53 & (137 & 141) respectively

[6] Examples are ibid: 187, 204, 238, 289

[7] Ibid: 92

[8] Ibid: ibid: 42 – 44.

[9] Ibid: 292

[10] Ibid 5, 141, 178 respectively

[11] Ibid: 109

[12] Ibid: 50

[13] Ibid: 170

[14] Ibid: 259

[15] Ibid: 205

[16] Ibid: 89

[17] Ibid: 106

[18] ibid: 130

[19] Ibid: 39

[20] Ibid: 253

[21] Ibid: 7

[22] Ibid 114 – 118

[23] Ibid: 220