In a historical novel, you can ‘meet’ people supposed in those fictions to be famous AND those who are or ‘were’ so in ‘real’ life simultaneously. In Neil Blakemore’s 2025 novel Objects Of Desire, the character named Christopher Isherwood says that people want fame: ‘So that they can become monsters and make others feel bad, and no one will dare challenge them’. Yet it is, he also claims an advantage of fame that one can ‘present a version of’ oneself ‘to the world that appears better than the version they fear they really are’. (my emphasis) [1]

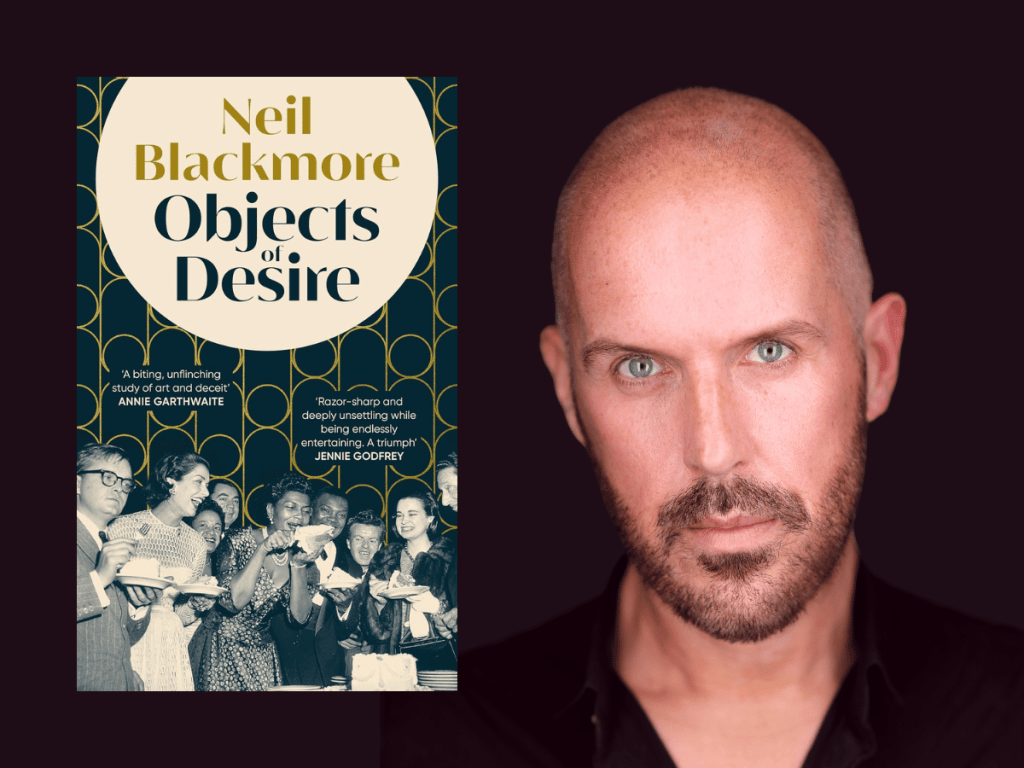

Fame is a thing with a date-stamp, hence I answer this question more indirectly than I usually do – which is always fairly indirectly. If you didn’t know that read Neil Blakemore’s new novel Objects of Desire. It focuses around a fictional ‘famous’ writer, Hugo Hunter, whose fame fades too between publication of the three novels in his name. It isn’t really his name, and there are other things underlying what I said that I won’t turn into spoilers. We know it is not his name for we meet him in chapter 3, called ‘Backstory’, as a young ‘effeminate’ literary boy in the Welsh valleys named Huw (who every English person pronounces as ‘Hugh’) Baker-Williams.

It is a name given him by his informal ‘agent’, Sonia Brownell, and the novelist, Angus Wilson in a setting that is a real literary pub, The Lamb and Flag, at Lamb’s Conduit Street (literary types even in my time as a student there pronounced it ‘Cundit). In a late scene, the now forgotten (actually already almost forgotten at this later time in the novel) ‘Angus Wilson’ meets Hunter on his literary tour in London at the same pub at which both he and Sonia (she is probably better remembered now than Wilson but as Sonia Orwell) gave him that nom de plume. Wilson recalls that when they gave him the name, it was actually a joke about the provincial young man’s thirst for FAME;

Don’t you realise that even your name is a joke? Hugo … Hunter. You are the Hunter of fame, …

… I never met anyone who relentlessly pursued fame as you. [2]

Hugo fulfils this pursuit not only in the famous name he seeks for himself but in the famous names he acquires, too, as friends. Even in a moment of despair about ‘fame’, when he thinks of it as being reducible to the gathering of ‘literary gossip’, his ‘literary life’ and his ‘famous life’ also reduce into a party in which the worst traits, including homophobia, of literary and socialite characters Philip Roth, Norman Mailer and Lee Radziwill are on show. He rejects ‘famous life’ then – but not in its entirety, for he still leaves the party with James Baldwin, whom with the less explicable other exception to rejected glamour, Gore Vidal, remain the two literary types that are redeemed – perhaps as much because they are both queer writers.[3]

But he is equally aware that some people lose their savour of fame. Hugo drops Angus Wilson because he undermines his pretence that all he has done was for the ‘love of literature’ rather than be an ‘object of desire’, in brief, someone famous or associated with something famous like a novel everyone desires to appear to have read, but one wonders whether that would have happened but that Angus’ ‘career had wandered, critics had not rewarded him for following his own muse. …He had only published two novels in the whole time since I had published Tricks. They had vanished into thin air’. [4] Wilson’s fame and its decline occurred, So much so that my shelves and memorabilia still include him whilst no-one I know even acknowledges him anymore (though I even have those two last (and bad) novels on my shelves). Fame is fickle and based on hearsay mainly – the names of novels as much unread as read. When Hugo previews his upcoming memoir in the UK he is asked who is in it from ‘English literary scene of the ’40s’.

“Elizabeth Bowen, Sonia Orwell, Angus Wilson,” I said, to absolutely no impact, only to the dimmest eyes. “George Orwell,” I added opportunistically, and their eyes lit up. “Oh, my hero! I live right by his flat at Canonbury Square!” [5]

Yet I suppose we buy and read this novel because it contains real ‘famous’ names – mainly Americans with infamy as well as fame like Vidal, and Truman Capote, or adopted as Americans. There is only one supposedly famed ‘Welsh faker’ (as he is called in the list entitled ‘The Objects’ of those famed persons and has some of them on .[6] Yet the issue with our ‘Welsh Faker’ is that all three of his novels – only one is written in the time of the novel’s apparent rewriting – are stolen from other unknown writers, writers without fame or in the category of ‘objects of desire’, though the last nearly gets into that latter category. And if a real debut writer’s work is stolen, it is good insurance to murder that novelist before publication of their debut novel worthy of stealing – with some refined literary editing. Those wronged writers are wronged twice then, their murders as sociopathically (the term is defined and differentiated from psychopathically) unfelt -but for nearly but not really in the last case – by their literature-loving perpetrator . The murders are good thriller fiction but I think they also serve as symbols of how the process of being one of the ‘forgotten’, those unknown to fame, comes about – through a culture that attributes to fame something more real than is there. A good writer can write and not achieve fame and, as soon in some cases, lose it. They can be killed by many forces – reluctant publishers, a sluggish book economy,bad (fair or otherwise) critical reception – and Hugo Hunter is such a critic. Hugo learns his about books first from the ‘seven hundred and something pages’ a book called How To Intrepret A Novel: An analysis of 250 Great Works of Literature.

Gore Vidal and Truman Capote with Tennessee Williams in the 1960s

This is as much a book about the social ‘ghosting’ of the has-beens or never-quite-made-its of literature, showing how much even queer literary celebrity involves jumping on contemporary bandwagons. For his first novel he takes a manuscript called originally Life and Death in an Office, from Nancy, a secretary without self-esteem or the social confidence that is the launching pad to the desire for ‘fame’ into a novel called Ordinary Girls, which ploughed the early taste in queer writing for the relationship between heterosexual cis girls and young gay men, Tricks is the John Rechy like name Hugo gives to a novel by a young gay guy called Paul with no social capital or skill (hence violent when frustrated) but lots of talent. Finally, he steals the lovely drug-taker, Dorff’s, novel (the character we get best to know and love) Untitled Novel about drugs ward relationships and turns it into a novel about AIDS when these are fashionable. In the end, killing in the novel is always related to stealing a commodity written by hand or poorer type of typewriter and turning it into the object of desire a certain society looking for its ‘literary’ reflection or talking point.

The people who come out best in this novel are the writers whose mission is not just for fame: Mailer, Roth, Truman Capote, whose term ‘objects of desire’ is taken by Hugo but, with the exception of Gore Vidal, the ‘masterpiece’ writers who use writing as a social mission – especially James Baldwin, though he is somewhat cracked by ‘fame’. and Christopher Isherwood (and not quite W.H. Auden – portrayed as a mercenary paedophile).They are people who succeed in loving and carrying love into care for the otherness of the beloved – even Sonia Brownell with the detestable Orwell.

Christopher Isherwood with life-partner Don Bachardy

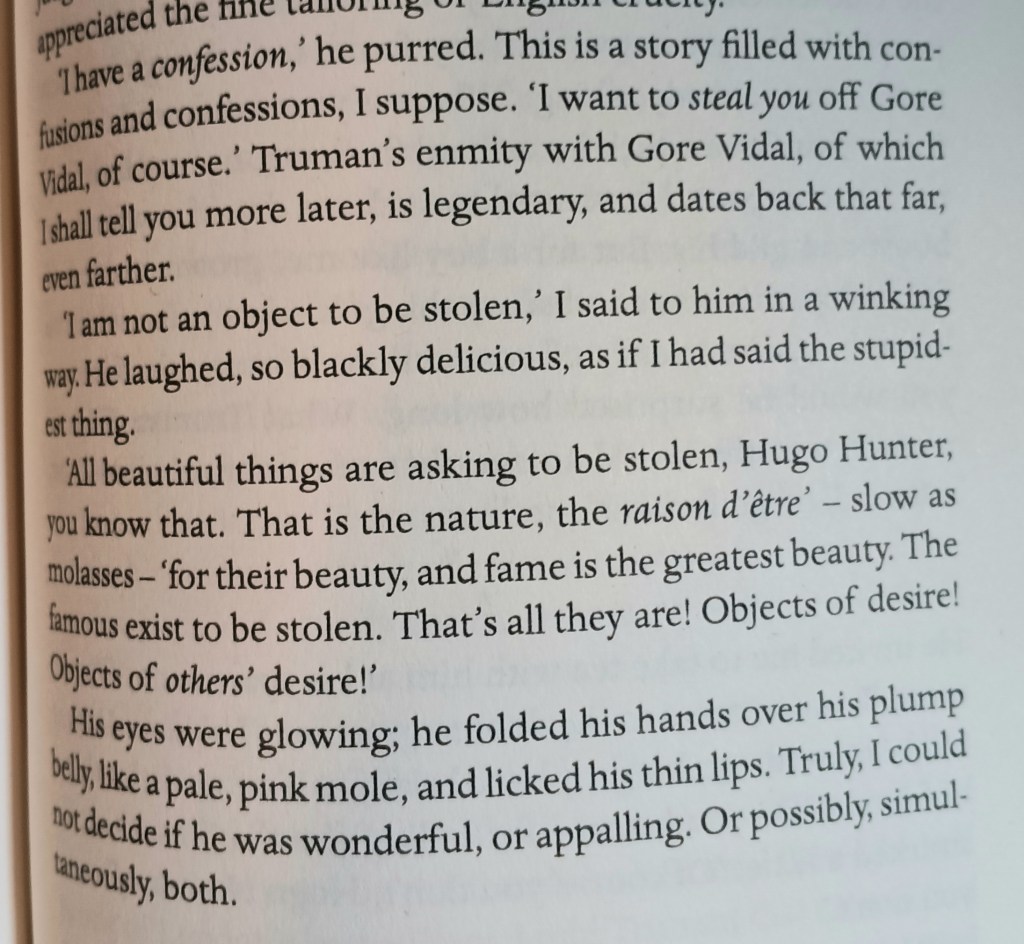

Let’s look at how the character Isherwood phrases the issue by filling out the references referred to in my title. At this point in the novel Hugo feels he is suffering as a result of his fame as a result of having a false identity projected onto him, and in this case by Truman Capote, who ‘is famous, and should know better’. Christopher laughs and eventually replies:

… “Do you know why people seek fame, Hugo?”

“Because they want to feel better about themselves?”

He nodded his head as if I was almost there. “Because they want to present a version of themselves to the world that appears better than the version they fear they really are. Smarter, funnier, hipper. They want the world to see that version of themselves andd not see the other underneath”

I did my impression of Sigmund Freud: “So they can believe it themselves.”‘

“Oh no,” he went, shaking his head “So that they can become monsters and make others feel bad, and no one will dare challenge them’. [1]

Is ‘fame’ then the access to social power and that alone; including the power that draws social attention to whatever self-image you choose. You choose it not because you believe in it but because you know that you are entitled to choose by fame, all that is necessary in order not to be challenged when you act as monstrously as you like. Looked at this way, the novel becomes a rather sharp satire on queer literature – it looks for that representation of the queer that is currently powerful and ignores the rest of us – the Nancy ‘fag-hags’ (the horrible term of the time), the damaged into violence Paul-boys and the ‘druggies’ who have not even the confidence to confront their social wants, as Dorff does not lest it invite in his own sexuality, except through Hugo.

Hugo manages and manipulates Dorff until he realises that though Dorff can give him the confidence to love someone and work in their interests he really wants his luscious manuscript to convert into a queer AIDS novel – dropping out the tragedies of drug dependency that elite societies create to absorb the forgettable. We can all be guilty of that.

This is a stunning and under-rated queer novel. I have never seen the dream of provincial queer boys of the 40s and 50s (me included) finding fulfilled freedom in ‘London’ (in ‘places like Camden Town and South Kensington, impossibly glamorous, all expressionist fog’) as well as it is done here. [7] The effect of homophobia from admired people – from George Orwell, for instance, is well done, as brutal as the beating given to Huw by his Dad and the latter’s mates for being discovered as being the passive sexual partner with another boy.

The extremes of care and violence against queer vulnerable bodies are beautifully done – I relished the asexual care given to Dorff’s battered body. And, more than anything, I loved a book that shows that queer literature must investigate queer attraction and repulsion with commitment before it seeks objectification as a famous example of itself.

I think also that Blakemore has more to say on this in his choice of Truman Capote as an important voice in showing how damaged queer people can be by life – a process of harm to young queer kids now continuing again more fully than before in the UK. There is a great ethical principle in the section below that references Helen of Troy about the fact that ‘objectification’ is a process queer people might have escaped had not queer desire been confused with the appearance value of fame, as if fame were beauty – not that which enters your heart silently.[8]

Do read this lovely book. It is unputtdownable! But not as shallow as it leads some critics to believe. I wouldn;t want to meet Hugo in the flesh but I learned a lot by meeting him in a fictional historical novel.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxx

____________________

[1] Neil Blakemore (2025: 204) Objects Of Desire, London, Hutchinson/ Heinemann, Penguin.

[2] ibid: 213f.

[3] ibid: 252ff.

[4] ibid: 310f.

[5] ibid: 305

[6] Prefatory material of ibid.

[7] ibid: 36f.

[8] The passage below this note above is from ibid: 175. Beautiful writing.

One thought on “In a historical novel, you can ‘meet’ people supposed in those fictions to be famous AND those who are or ‘were’ so in ‘real’ life simultaneously. In Neil Blakemore’s 2025 novel ‘Objects Of Desire’, the character named Christopher Isherwood says that people want fame: ‘So that they can become monsters and make others feel bad, and no one will dare challenge them’.”