Let’s answer this prompt as if Thomas Mann were justifying his last novel: the ultimate ‘game’ – of confidence tricks and roleplay. In a diary entry from 25th November 1950, Thomas Mann calls his final and unfinished picaresque novel Felix Krull ‘my homosexual novel’. Yet the case for seeing it as that perhaps reduces to a few references to passing moments of bisexual or queer desire, a portrait of the Scottish laird Strathbogie, some (as claimed by Mann’s lesbian daughter Erika) heterosexualised versions of real queer love encounters, and what Jeffrey Schneider calls its ‘affinity with the aesthetics of gay male camp’.[1] This blog holds my thoughts on my recent reading of Thomas Mann (trans. Denver Lindley) [1997 Minerva Paperback from ed. of 1954} Confessions of Felix Krull, Confidence Man: Memoirs Part 1 London, Mandarin Paperbacks

I decided to read Thomas Mann’s Felix Krull after reading and blogging on Jeffrey Schneider’s (2023) Uniform Fantasies: Soldiers, Sex, and Queer Emancipation in Imperial Germany, who tells us that this is the novel . You can read the blog if you wish at this link. It is often called a picaresque novel and this may suggest how best to tolerate the unfinished nature of the story and the rather directionless feel that episodic novels have always had after their heyday in the seventeenth and eighteenth century: witness Pickwick Papers for instance. But read that way at least you might enjoy the splendour of the humorous but nevertheless fine handling of incidents in a comic style that has the depths missing from Pickwick. However, it is also obviously a bildungsroman, an story of moral and character development told in the first person, usually by a narrator of varying reliability. Mann also says, claims Schneider, that in his novels “all of it is autobiography”, but if so he also suggests that it must be heavily disguised autobiography.[2] This perhaps may matter more to queer readers attracted to the novel by knowing that, in a diary entry from 25th November 1950, Thomas Mann calls it ‘my homosexual novel’, as Schneider reminds us. [3] Nevertheless, if we are armed with that idea combined with even the thin knowledge of the biography of the writer supplied for this book by Google, we might expect that here a great European writer might have left us a queer autofiction based on his own life. Here is what Google says:

This picaresque novel was written in three phases: 1910-1911, 1912-1913 and 1950-1954. By the middle of 1911, most of Book One was complete. At this point the novel was interrupted by the writing of Death in Venice from July 1911-July 1912. After completing Death in Venice, Mann returned to Felix Krull, writing Book Two up to and including the army medical inspection scene (Musterungsszene) and the first draft of the Rozsa episode (Book Two, Chapter 6). Mann then abandoned the novel again in the summer of 1913 to begin work on The Magic Mountain. Mann resumed work on the novel almost four decades later in December 1950. In the summer of 1950, whilst staying at the Hotel Dolder in Zurich, aged 75, he had fallen in love with a young hotel waiter called Franz Westermeier. Then, in November 1950, he read Gore Vidal’s homosexual Bildungsroman The City and the Pillar (1948). These experiences encouraged Mann to resume work on Felix Krull. The novel as it stands is incomplete, and is subtitled ‘The Memoirs, Part One’. Mann envisaged a second volume describing Felix Krull’s adventures in South America. Felix Krull attracts, and is attracted, to both sexes, and the novel describes his light-hearted erotic adventures.[4]

After all the expectations of a ‘frank’ and open bildungsroman novel, perhaps like that pioneer novel by Gore Vidal, Felix Krull must eventually dissatisfy. If you are looking for a novel of queer development and adventure, then you may too find the novel very disappointing, whilst still enjoying many very funny episodes within it.

Indeed Schneider is after all that largely circumspect in finding this a ‘homosexual novel’ other than in its ‘affinity with the aesthetics of gay male camp’.[5] His argument about the novel’s style and his references to Thomas’ lesbian daughter (once in a marriage of convenience with W.H. Auden), Erika Mann’s beliefs about the novel as transposing heterosexual with queer sexual affairs can be read in his book and this is not my interest here. Instead, I want to pursue those few open references to queer sexuality in the book, for I find them extremely interesting and perplexing not least in their constant attempt to find appropriate explanations of queer desire – in, for instance, the German literary tradition of the doppelgänger, and in repeated episodes in which there is a splitting of desire in forms of the pursuit of two or more sexual objects within and between their own or others’ definitions of sex/gender. And disguise by change of clothes and use of other prosthetics is a constant possible ploy in the novel, for Felix is brought up to please his godfather by continually changing the form of his clothing for the latter’s delight.

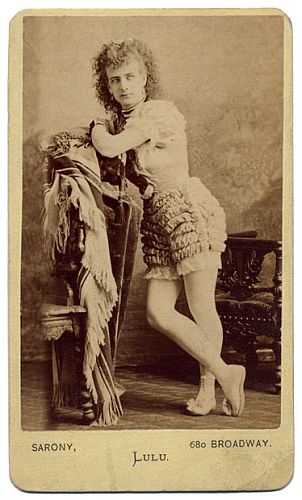

And the tone of the treatment of the potential for sexual duplicity, which it might be possible to enjoy, is perhaps always there – and indeed possibly justifies Erika Mann in believing that the descriptions of heteronormative sex within it are disguised queer encounters. For instance, in his leisure time from his role working in a Paris hotel Felix, by then (by direction of management) known as Armand, after the role of the lift assistant he replaced, he visits the variety artiste’s theatre with dubious trickster friend Stanko to find out what ‘fabulous creatures these artists are’. There he notices people so covered in ‘masks (sometimes made from their supposedly natural faces pulled into ‘insane smiles’) that he wonders if they could ‘conceivably find a place in ever-day life’ or whether, indeed they are human at all instead ‘exceptions, side-splitting monsters of preposterousness, … cavorting hybrids, par human and part insane art’. Amongst these he discovers a trapeze artiste who calls themselves Andromache, after the tragic queen from Euripides’ The Trojan Women. An impressive sight, Andromache evokes a feel of a body either animal or angelic. Yet Andromache’s body is liminal in other ways, ‘more than average size for a woman’:

Her breasts were meagre, her hips narrow, the muscles of her arms, naturally enough, more developed than in other women, and her amazing hands, though not as big as a man’s, were nevertheless not so small as to rule out the question whether she might not, Heaven forfend, be a boy in disguise. No, the female conformation of her breasts was unmistakable, and so too, despite her slimness, was the form of her thighs.[6]

A carte de visite photograph of Lulu, the ‘female’ trapeze artist formerly known as the boy acrobat El Niño Farini, who was actually Sam Wasgate (1855-1939), … (carte de visite photo: Sarony, 680 Broadway, New York, probably 1873). By Footlight Notes See https://footlightnotes.wordpress.com/2014/06/01/a-carte-de-visite-photograph-of-lulu-the-female-3/

This is the tonal quality of the novel we need to understand. At this point, Krull, despite his experience of the adventures possible in disguise, or even a change of clothes, is very ready to avoid any suggestion that the markers of biological sex might not be harder to interpret than he, at this point (but not everywhere) wants them to be. He protests (too soon we might think that the evidence of breast and thighs in Andromache are irrefutable despite the fact that her hands might be said to be those of ‘a boy in disguise’. You cannot get clearer than this the knowledge that even the biological markers of sex vary independently from each other along a continuum of male and female and that final decisions on sex/gender are often made on social and cultural expectations: the force of ‘Heaven forfend’ will depend entirely on tone but invokes religious sanction for biological sex,- or does it? Is it spoken with irony, or repressed excitement. Would Krull like there to be a ‘boy in disguise’ behind Andromache’s ambiguous female sex markers? There is after all evidence already encountered by the reader that the nature of Felix’s desire may be complicated by moments of a complex bisexuality (where desire is elicited only in the existence at the same time of bodies both male and female, desire that would not exist otherwise for either the male or female) and perps associate with an obsession with the mental image of the androgyne (one figure both male and female simultaneously).

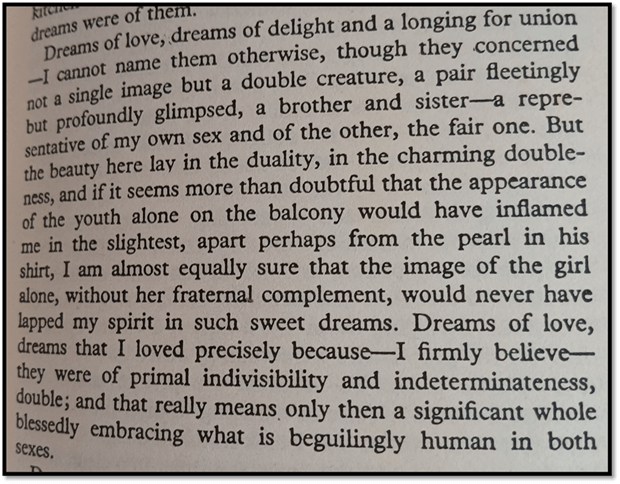

Early in the novel but after the suicide of his father and whilst still a boy on the edge of young manhood, he travels with his family to set up a modest lodging house in the large city of Frankfurt am Main which the family call Pension Loreley, after the bad champagne manufactured by his father that ruined him financially, but also in honour of the seductive maidens of Homeric myth. In love with the appearances of shop-windows and theatres, ‘the treasures of the decorative industry, such objects of high visual lust as … small bronze statues, and I would have liked to pick up and fondle those poised and noble bodies’, he is in heightened state when he sees on an ‘open balcony of the bel étage of the Great Hotel Zum Frankfurter Hof.’. Upon this ‘stage’ steps ‘two young people, as young as myself, obviously a brother and a sister, possibly twins – they looked very much alike – a young man and a young woman moving out together into the wintry weather’.[7] This is the stuff of a fantasy of the ‘double’, in which Felix sees not only the image of his own desire and wished for state – a kind of narcissist’s double but sees it in a double form, divided only by sex/gender difference.

Felix elaborates this as if it were a parable of the constitution of desire, as it must be for him. It is interesting that though he claims neither of the young pair alone would have ‘inflamed me’ if alone but excepts a nuance about the boy wherein, in his female companion’s absence, he might still have inflamed Felix by virtue of ‘the pearl in his shirt’.[8]

It is a complex image of three-way doubling, that demands that Krull be satisfied only in the presence of both forms of sex/gender apparition, and then dressed in the fancy of stages and ornament. When we return to the ide of doubles exciting Felix’s desire it is for a mother and daughter (women who look similar but for age) but which satisfy desire that time in the ‘image of a girl’, with ‘her’ (this time) maternal not ‘fraternal complement’. When he refers back to that episode he says that falling in love with mother and daughter simultaneously is again ‘being enchanted by the double-but-dissimilar’[9] This is what I meant above, I think, by the book absorbing its queer content into discussions (there are other instances) of ‘constant attempt to find appropriate explanations of queer desire – in, for instance, the German literary tradition of the doppelgänger, and in repeated episodes in which there is a splitting of desire in forms of the pursuit of two or more sexual objects within and between their own or others’ definitions of sex/gender’.

Will this satisfy those looking for a queer bildungsroman in Felix Krull? No. But it feeds into Schneider’s view that decorative style in this novel is examined in terms of fictions, deceits ‘confidence-tricks’ and even putative (from some perspectives ‘lies’ and ‘deceit’ (where you can in dressing up become anything you wish to be). This is at the root of the ‘confidence man’ theme for it is clear that in some ways Krull can be the ‘double-but-dissimilar’ to the young Marquis de Venosta whom he sees ‘apparelled like me’. The later parts of the novel involve Krull and Venosta exchanging roles because the latter must ‘become two people’ in order at the same time to obey his parents (and protect his inheritance) and live with the woman he wants. At one point their names become one: we are one and the same: Armand de Kroullosta is our name’.[10] Venosta’s beloved is named Zara, and, to complicate the picture of desire further, Krull at times wants her too and doubles her with his later conquest Zouzou, where the ‘Z’ in the name is but the beginning of their doubling, to the point of Krull drawing images that meld the former’s body with the latter’s head.

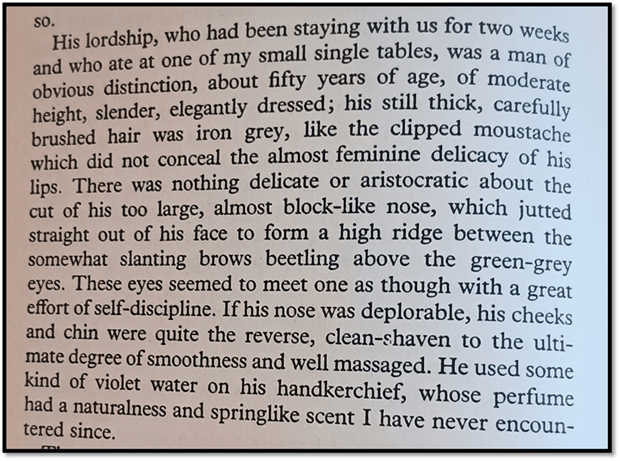

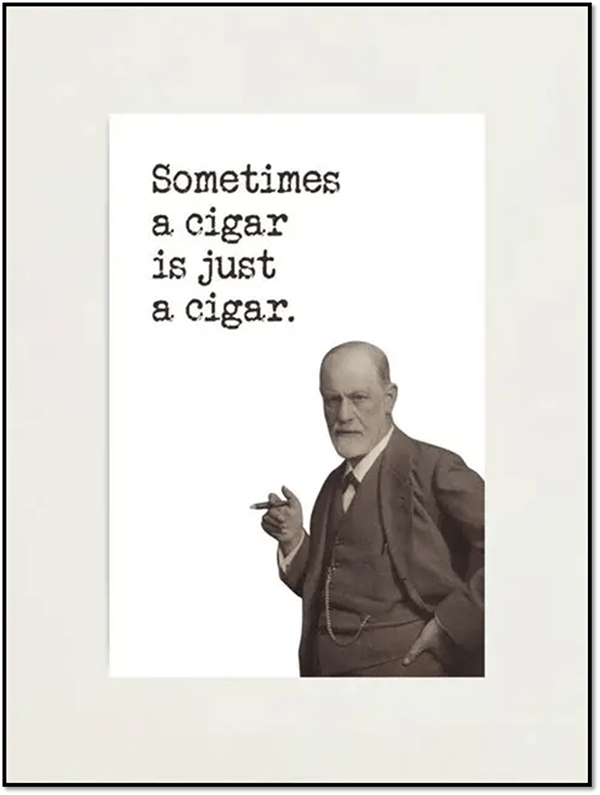

But there are other ways in which queer desire is discoursed in the book, and perhaps autobiographically. Look for instance at the episode (again starting with a ‘double-but-dissimilar’ context, but in this case very dissimilar, where Felix is pursued by two lovers – one the girl from a rich American bourgeois family (Eleanor Twentyman), the other a fossil from an old Aberdeen-based aristocracy, Lord Strathbogie. I cannot discover why Schneider in his account calls him Lord Kilmarock, unless there are complicating textual factors that occurred between the translation from German to English.[11] Here is the description of Lord Strathbogie:[12]

It is an excellent description of a man divided by blockish masculine features – that nose – and a ‘feminine delicacy’ that shows in the lips, and is complemented by the scent of spring not usual to men at the time (Kull ‘never encountered it since’). But then I examined two pictures of Thomas Mann himself (below):

Are there not deliberate markers of Mann found in Strathbogie, especially that nose? If so, there is in the novel something well below its ironic playful comic surface and the fantasy treatments of bisexual desire. Strathbogie delights in discovering the doubling of Krull’s name as ‘Felix’ and ‘Armand’ but seeks to address the former – the authentic person underneath his masks. He offers Felix a role in his Aberdeen castle above that of service but not secure, as Krull quickly works out, with regard to a future after the Lord’s death (the latter tells him some rich men have adopted their convenient young men but wonders if such an arrangement would have ‘proper authority’).[13] Moreover Felix has not abandoned his love of appearances and makes little of a man who can have ‘so delicate a mouth and such a block of a nose’.[14] Strathbogie is though that figure we see in other more closeted literature of the period, the lonely man confined to ‘singleness’ and solitude. There is the mark of that very different novel (Maurice comes to mind) in this piece of (almost) bathos, where it not sacred to me as the expression of past queer oppression. Strathbogie begins as if dominant a person whose wishes matter but ends differently:

“… Come with me! It is my wish.”

He took one of the cigars I had recommended, regarded it thoughtfully from all sides, and passed it under his nose. No observer could have guessed what he was saying as he did so. What he said softly was: “It is the wish of a lonely heart.”

Who so inhuman to reproach me for feeling moved?[15]

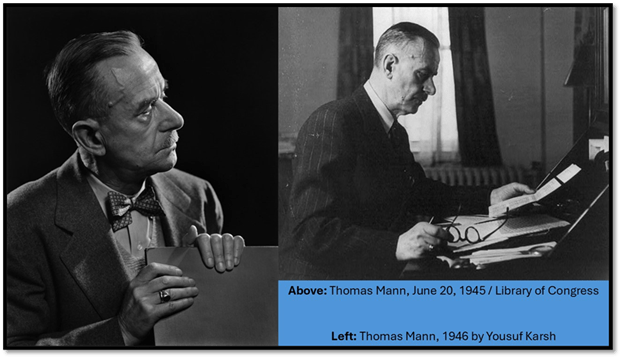

Felix is not moved enough to go with Strathbogie. Perhaps it was the nose so featured here or the financial insecurity of a real social world. We cannot know for sure in so deceptive a man as Krull in explaining his motives. What we can know is that communication here occurs on very different levels, and however much we remember Freud’s dictum that ‘sometimes a cigar is just a cigar’, we also remember that there is no evidence that he ever used those words:

And having sent Strathbogie back to his castle to find another working boy to fill his lonely heart and bed on Krull’s advice, there is still further evidence beyond the theories of narcissistic desire before invoked. Strathbogie is not the first of the ‘men of a certain sort’ who are mentioned in the novel in that reductive phrase assumed to be well understood by any reader. With a wink, and taking the worldly reader into his confidence, Krull mentions that he turned down those very men with courtesy when:

… unwelcome proposals (I assume the reader schooled in the multifarious world of the emotions will not be astounded) were made to me from time to time in more or less veiled and diplomatic language …’[16]

Krull believes that his truly aristocratic nature is revealed freely and truly only when he is naked, though he does not tell us what aspect or organ of his naked body reveals this superiority before other men, even though he is certain that it is nakedness alone that ‘proclaims the naturally unjust constitution of the human race’. Suffice it to say he interpreted whatever was the sign of a noble male body from the drawings done of his naked body by his godfather Schimmelpreester.[17] Felix assumes everyone is aware of a the ‘multifarious world of emotions’ including those between men and those which force men not to reveal those emotions.

Schimmelpreester sends Felix, his godson, into the care of a hotel manager in Paris called Stürzli without telling us much, while hinting a lot, about the nature of these men’s friendship. Felix knows however that he is likely to get what he wants from Stürzli when he is being interviewed for a role (even that of an unpaid lift control assistant)if he not only elevates the man’s rank (as he does to all he wants something from) but also ‘discreetly drawing somewhat closer’ to him. When Stürzli reacts with an ‘expression of revulsion’ on noticing this, Krull clearly interprets this symptom in the manner of Freud interpreting denials a wish as the very opposite of negation or negative response to those wishes or positive feelings. Stürzli, Krull assumes acts revolted precisely because he wants Krull’s body to touch nearer to is and because he positively desires the ‘youthful beauty’ of the boy:

By this I mean that those men whose interest is wholly concentrated on women, as was no doubt the case with Monsieur Stürzli with his enterprising imperial and his gallant embonpoint, when they encounter what is sensually attractive in a person of their own sex often suffer a curious embarrassment at their own impulses. …; the result is just this reaction, this grimace of revulsion.[18]

The whole passage is wonderfully evasive and potentially ironic and not even sure of thee things it claims to be sure – that Stürzli’s primary sexual desire was for women at all.

In a novel where donning clothes, or assuming nudity, for the purposes of his godfather’s appraisal of him in a painting, Krull’s childhood assumed that all art was a matter of acting natural in what was not natural. It was possible to assume ‘whatever the costume, the mirror assured me that I was born to wear it, and my audience declared that I looked to the life exactly the person whom I aimed to represent’.[19] The audience of course was one man, godfather Schimmelpreester’, who claims to calls himself the High priest of Nature, which he also calls ‘mould’ or decay. Yet the Nature Schimmelpreester offers to Felix is the deceptive appearances of Art. Strangely Felix always chooses to limit what he says about him ‘in this place’.[20]

This very childhood experience launches Felix into a career where only to exchange clothes, or indeed to exchange clothes for nudity, is to raise another identity for exploratory use and the ability to later turn such deception to his advantage entirely. Everyone acts up to a role wherein they see themselves grander than they are – it is why people react well to be given elevated rank by being awarded a Superior name – Krull does while being tested for fitness in the army, as well as to Stürzli. He calls Zaza, ‘madame la marquise’, knowing that it is her aim to get this title by marrying Louis, Marquis de Venosta, but Krull beats her to the post by using Louis’s sexual desire for an ‘inferior’ that he will never ever marry in reality, to take Louis’s name (and title) for himself in an exchange of clothes and financial provisions.[21] When dining with Zaza and Venosta, the latter jokes to Krull that Krull ‘wouldn’t mind’ exchanging roles with him at dinner – Felix being served and Venosta the waiter. Krull’s savoir faire is remarkable:

How strange that he should have put into words the preoccupation of my leisure moments, my silent game of exchanging roles!

The theme of ‘exchanging roles’ is also a kind of roleplay game but deadly serious in its effect. Even with gameplayer Zouzou, Felix will get the better. But we will never know for sure because the second and possibly third volume of the novel do not exist. My own feeling is that novel never got finished because Mann lavished all his wit and humour on its gaming and roleplay at the expense of understanding these features as part of his analysis of the nature of desire, and queer desire in particular. To have written ‘my homosexual novel’ was an impossibility to him – and to cover it up entirely in a picaresque diversion would cost more time than he had – he died in the process of returning to it yet again after many earlier attempts.

So this is the end of my speculation. But I am not the only person to wonder how much Mann veers in this novel from any focus at all. Nasrullah Mambrol argues in a blog in 2022 that at the end of the extant novel ‘many intense, at times convoluted, deliberations that now occur—often focus on astonishingly complex matters, such as the “different forms and representations of life” or the Moorish, Gothic, and Italian elements, including the Hindu influence, of “architectural styles of castles and monasteries,” are sometimes so abstruse that they serve no purpose in a novel of character. She concludes that the game has taken over but by now it is Mann’s game to show that the philosophical novelist he aspired to be is itself a game wherein an:

… unusual situation seems to profoundly animate and entice Felix, who looks upon these supposedly problematical issues with a fervent and immediate desire to enact the best role he has ever played. In fact, his unexpected responses suggest he has achieved the epitome of his role as a comic criminal and arch deceiver. The confidence man Felix Krull understands only too well that to win the consensus and benevolence of others, one must express what the opponent wants to hear—or, as the situation may be, to enact the role his challenger desires of him.[22]

What Mambrol is perhaps suggesting – and if not I will – is that Mann is coming clean about Krull being a role that the author is playing in the genesis of his own philosophical turn. Mann is enacting and facing him with the questions of interest to a philosopher that, up to this point, Krull has never shown any sign of being able to become. However, if it is true , as Schimmelpreester asserts of him, that ‘in each disguise I assumed I looked better and more natural than the last’, then the last disguise he takes on would be the natural philosopher risen over all other roles to interpret the world to itself. But no wonder the queer novel got lost in the process. I for one think this a pity.

Bye for now.

With love Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Jeffrey Schneider (2023: 152f.) Uniform Fantasies: Soldiers, Sex, and Queer Emancipation in Imperial Germany Toronto, University of Toronto Press.

[2] Ibid: 152

[3] ibid: 153

[4] Google on German Literature – Felix Krull available at: https://sites.google.com/site/germanliterature/20th-century/thomas-mann/felix-krull

[5] Jeffrey Schneider op.cit : 153

[6] Thomas Mann (trans. Denver Lindley) [1997: 204f. Minerva Paperback from ed. of 1954} Confessions of Felix Krull, Confidence Man: Memoirs Part 1 London, Mandarin Paperbacks.

[7] Ibid: 86 – 88

[8] Ibid: 89

[9] Ibid: 305

[10] Ibid: 268

[11] Schneider, op.cit: 152

[12] Mann, op.cit: 226

[13] Ibid: 235

[14] Ibid: 229

[15] Ibid: 231

[16] Ibid: 117

[17] Ibid: 99

[18] Ibid: 155

[19] Ibid: 26

[20] Ibid: 27

[21] Ibid: 239

[22] NASRULLAH MAMBROL (2022) ‘Analysis of Thomas Mann’s Confessions of Felix Krull’ (October 10, 2022) Available at : https://literariness.org/2022/10/10/analysis-of-thomas-manns-confessions-of-felix-krull/#google_vignette