‘The linoleum, too, … is blue. So blue you’ll have the feeling of being swept away because you are, into a current of corridors intentionally too narrow to turn around in’.[1] Queer writers have so long challenged the false universals of heteronormative stability, and perhaps privileged the discourse of sexual interaction as a panacea for the loss of universal connections, we may have forgotten that our role on earth is to rediscover what, if, anything is universally the case about inevitabilities of life and death amongst the world’s diversities and contingencies. Those universals must include consciousness of the fate of Emperor hogs, as well as those we might describe as ‘Soft, simple people, who live only once’.[2] This is a blog on Ocean Vuong (2025) The Emperor of Gladness London, Jonathan Cape

First of all, I need to apologise for my portentous title, especially that apparent attempt at being sage about the purpose of life: ‘we may have forgotten that our role on earth is to rediscover what, if, anything is universally the case about inevitabilities of life and death amongst the world’s diversities and contingencies’. I can only excuse this by saying that I think Ocean Vuong takes on precisely that role, almost as the Mid-nineteenth-century Sages did, in order not to give in to despair about the role of the modern writer in an age where voices have become specialised to serve distinct identities – fragments of humanity not the whole. Modern writers are too savvy to consider the role a universal one – as Dante or Sir Philip Sidney did.I think it is worth reminding ourselves of Sidney, whom I know more about than Dante, by referencing the Poetry Foundation’s excellent summary of the former’s definition of the poet from The Defence of Poetry. As always with Renaissance scholars, Sidney starts with classical authorities on what the name of poet betokens:

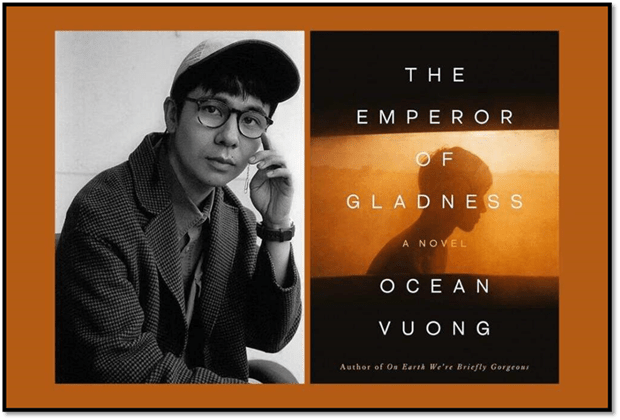

For this reason the Romans called the poet vates, “which is as much as a diviner, foreseer, or prophet,” such as David revealed himself to be in his Psalms. With equal reverence the Greeks called the poet a “maker,” as do the English (from the Greek verb poiein, “to make”). In all cases true poetry makes things “either better than nature bringeth forth, or, quite anew, forms such as never were in nature.” Nature’s “world is brazen,” Sidney argues; only the poets bring forth a golden one.

Sidney accepts Aristotle’s definition of ‘poesy’ as ‘ an art of imitation, for so Aristotle termeth it in the word mimesis–that is to say, a representing, counterfeiting, or figuring forth–to speak metaphorically, a speaking picture–with this end, to teach and delight.” But he quibbles with what the poets imitates, as already suggest above – not the fallen world of named after base metals (thus ‘brazen’) but the world before the Fall of Man in either Classical or Christian terms. I emphasise this for Ocean Vuong has much to say about falling and the fallen. The best poets are, to cite the Poetry Foundation summary again: ‘divine poets who imitate the “inconceivable excellencies of God,” of whom David, Solomon, and pagan poets–Orpheus, Amphion, and Homer, “though in a full wrong divinity”–are cited as examples; poets who imitate “matter philosophical,” of which there are four subtypes (moral, natural, astronomical, and historical); and “right poets.”

The right poet is then set off against other masters of “earthly learning” who claim to lead men to “virtuous action,” an ancient contest developed at length in Aristotle’s Poetics. The poet’s principal competitors are two: the moral philosopher, a figure of “sullen gravity … rudely clothed … casting largess … of definitions, divisions and distinctions” before him; and the historian, “laden with old mouse-eaten records,” who knows more about the past than his own age, who is “a wonder to young folks and a tyrant in table talk.” The philosopher maintains that there is no better guide to virtue than he who “teacheth what virtue is; and teach it not only by delivering forth his very being, his causes and effects, but also by making known his enemy, vice, which much be destroyed, and his cumbersome servant, passion, which must be mastered.” ….

The poet, of course, “standeth for the highest form in the school of learning” because he is the moderator between the philosopher and the historian. Through the art of mimesis the poet unites in one event the philosopher’s precept and the historian’s example. Rephrasing his earlier argument on fore-conceit and image, Sidney proclaims that the poet gives “a perfect picture” of something, “so as he coupleth the general notion with the particular example.” [3]

Forgive me for this long digression – but believe me it helps. That is because The Emperor of Gladness takes up again the same cudgels as did Sidney, and Aristotle whom the latter cites, to weigh up the claims of philosophy, and especially history, in order to implicitly favour neither but rather to promote ‘the highest form in the school of learning’: poetry. Of course, this being the twenty-first century it is not poetry alone (even less poesy) although the same metaphor of ‘Maker’ applies, that is lauded by Vuong but writing and the vocation of the writer. In this sense alone he differs little from the ‘sages’ of nineteenth-century writing, like Thomas Carlyle, John Ruskin, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and Walt Whitman. All of these people looked to restore a universal discourse of humanity that spoke through story of specific examples of the lives of a credible persons.

Yet I have to be honest here: Ocean Vuong was introduced to my attention at first as a queer artist and he remains a queer artist. I turn to Ocean Vuong, when I do, because they are feted by the people with whom I identify – queer people. This makes them in my mind, at least before I read them, as the voice of only a part of the repertoire of persons, and the meanings that matter to that particular grouping as they seek to interpret modern life. However, the ambition of their novels (and perhaps the poetry but I do not deal with that here) forces any reader to understand a much wider framework of meaning than queer particulars.

If you read through this novel looking for its queer content, you find very thin pickings indeed – like a long-delayed brief hook up between Hai and a beautiful mechanic, who later happily marries a woman and has children. It includes other partial non-heteronormative themes, upon which meanings are hung, like the concept of family (biological and / or chosen or an interaction thereof), community, work and the interaction of particular and ‘transcendent’ or universal concepts of time, such as belief in either the eternal or the unimaginable endless continuum of changed particulars.

No wonder Hai, Vuong’s protagonist, has Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse on his person in the opening of the novel, makes constant reference to Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five, Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov and Kawabata’s The Snow Country.[4] All of these novels seek to present truth through fiction understood as a higher form of truth than simple copies of the tepid beliefs of single nations (especially nations who define themselves by being at war with other nations) or other groups of class, sex/gender, nation and even of ‘sexuality’. Hai defines himself, as we shall see against the claim of being a writer and a reader – often seeing himself in real, if rather informal) or invented libraries.[5] These novels seek pathways towards some larger illumination, lying off land from the territorial spaces, sometimes floating in the middle of an Ocean – but which Ocean? Is it that on which boat people float to new lives, or those gaps between nations and interest groups who seek truth only in their own image or inside one aspirant writer called Ocean?

Hai starts the novel having run out of paths to take, out of ways to salvage his failures’, and wonders whether the certain flow of a river into mortality be better than the road over King Philip’s Bridge.[6]

A quest to find life meaningful outside the end of the particles (even such a particle as an Emperor hog) that are born, live a duration, and then die is precisely what George Eliot, Virginia Woolf and Ocean Vuong have in common as novelists. They all yearn for something more universal that links everything living without giving in to the mythologies of established religion or prescribed beliefs that offer meanings that console at the cost of subjection to their God or Gods, or emperors and presidents that pretend to this role. Against this is the act of serious writing that embraces the ethical and examined life believed in by Socrates.

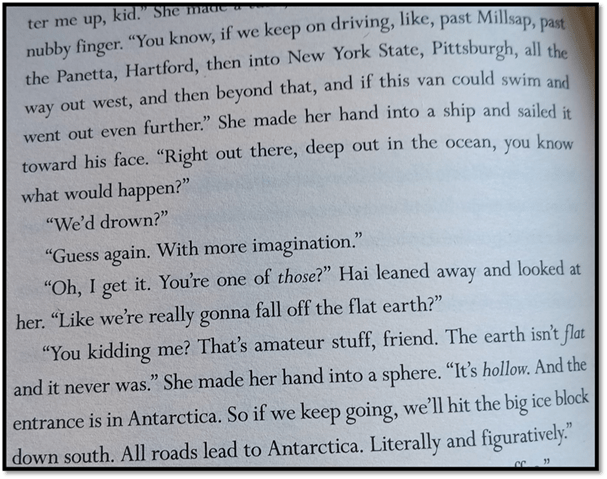

Meanwhile, in our quotation above, Hai only half-hears Maureen for his own vision too is transforming the world into something that looks like a lost world: ‘staring at the abandoned cars along the shanty lots, some so flat and rusted they looked like fallen trees’.[8] And I think it would be foolish to dismiss that a journey ‘deep out in the ocean’ (with its multiple characteristics of different kinds of space – depth, externality and interiority – which needs to be understood ‘With more imagination’ is the Ocean we are already learning to know – the writer Ocean Vuong, a monarch of the oceanic imagination. And this reading, if accepted, would put Vuong in strong company as a novelist -including those examples he cites. George Eliot gave up God and immortality early in her life, but continued to believe the purpose of fiction was to seek some meaning in facing the big themes of what is was that justified knowing only about particular relatively short lives, including one’s own particularity, lived only once (The Emperor of Gladness starts: “The hardest thing in the world is to live only once”) and rounding off in death.

Take, for instance (mainly in the section photographed above) this one example of the many paths, roads and rivers ridden by Hai and others, in various vehicles (sometimes of the imagination – one being a bathtub in which he rides all night through the old memories of Grazina of an Ancient European nation under attack by a fascist state and faux-Communist state,[7] although otherwise he travels in cars well or ill driven, on motorcycles he has borrowed – to find various examples of empty space, seemingly endless. In these spaces the truths we once held seem partial and the real truths are frightening, even if distorted by the ‘madness’ of Maureen who says that world leaders, in her rather distorted paradigm of capitalism, serve the interests of giant lizards who ‘feed on’ negative energy: ‘our suffering, ya know? We’re nothing but a crop to them.. They let us live our little troubled lives, let the sunlight and the rain make us grow … then, once in a while, they mow us down to keep their numbers up.”

Hai knows, and the woman who ostensibly saves him from suicide on the bridge at East Gladness, Grazina, can see that he is a ‘bookworm’ but she does not know what the meaning of his reading is in terms of his half-believed dreams of a future that he thinks may have passed him by: “ I used to want to be a writer. My dream was to write a novel that held everything I loved, including unlovable things. Like a little cabinet.”[9] That metaphor of holding matters and is a motif of the novel – for it references the memories that elsewhere fall away with time (most dramatically in Grazina’s, and her husband’s, respective dementias – unless placed into some context of the enduring. Yet some people do ‘learn by doing’ to write in places where ‘students dressed like the author photos of books they’d yet to write’. He feels he hears about such ‘unimaginable places, such utopias’ far too late, having no direction to his journey: ‘the path invisible until he’s long past their junction’. Yet The Emperor of Gladness will throw up endless of such journeys and paths in which direction is lost or the way blocked. And perhaps that is the source of the universal left – an imagined Ocean on which our so called ‘migrant’ pathways take shape, provided we float above their depths.

And, like past authors, Ocean Vuong has recourse to great interwoven mythologies – of fallen angels and fallen persons (or ones that resist falling and stay on the bridge). The section of the novel ‘Fall’ is one such myth – of ends that lead to apparent deaths, except when reminded of spring again (the cycle that structures this novel, but not without heavy irony). The bearers of Spring metaphors are charlatans and fools, who have no real understanding of loss, and the ‘losers’ they despise – for those who know the truth that resurrection has failed them, like Sony – acknowledge at last the guiding knowledge that death is universal, even of his father. On the scene of the latter’s death:

A woman in neon-green yoga pants with her hair in a ponytail jogged by with a blue-eyed husky in tow. “Spring’s here!” she shouted, too loud for the distance between them, then took a performative inhale. “You can literally smell the growth. Enjoy your hike, guys!”

The myth of resolution of the consequences of downturn in ‘growth’ speaks volubly here – whether applied to politics, economics or counselling psychology – it is all ‘performative’. But not all of it is false. Grazina unlike the neon-green goddess simply reminds Sony that he experiences the ‘same story’ of humanity: “Okay? Don’t be too sad, boy. You still have your hands. And with these what you make is yours.” – remember the etymology of the term ‘poet’ in the ‘maker’[10] There is as much faith in making as a universal philosophy as Ruskin and Carlyle found in the concept of work, and work certainly is the main form of ‘making’ in this novel – whether of written novels, pizza bagels or innovative forms of cornbread. But the limitation of the achievement of human making is absolute and a condition of accepting human imperfectability, rather than creating images of perfection that are purely rhetorical. Hence the ‘fall’ that recurs in the novel – from that one not taken by Hai from the Bridge to the recurring nightmares of Grazina, at the hands of inhuman ideologies – versions of both the Fascism and the Communism which over-ran her Hungarian home. As it rains and storms, ‘Grazina begins to scream’:

A sound like someone falling through air without ever touching ground, her voice pierced the thin walls with the hellish mix of a yodel and a howl.[11]

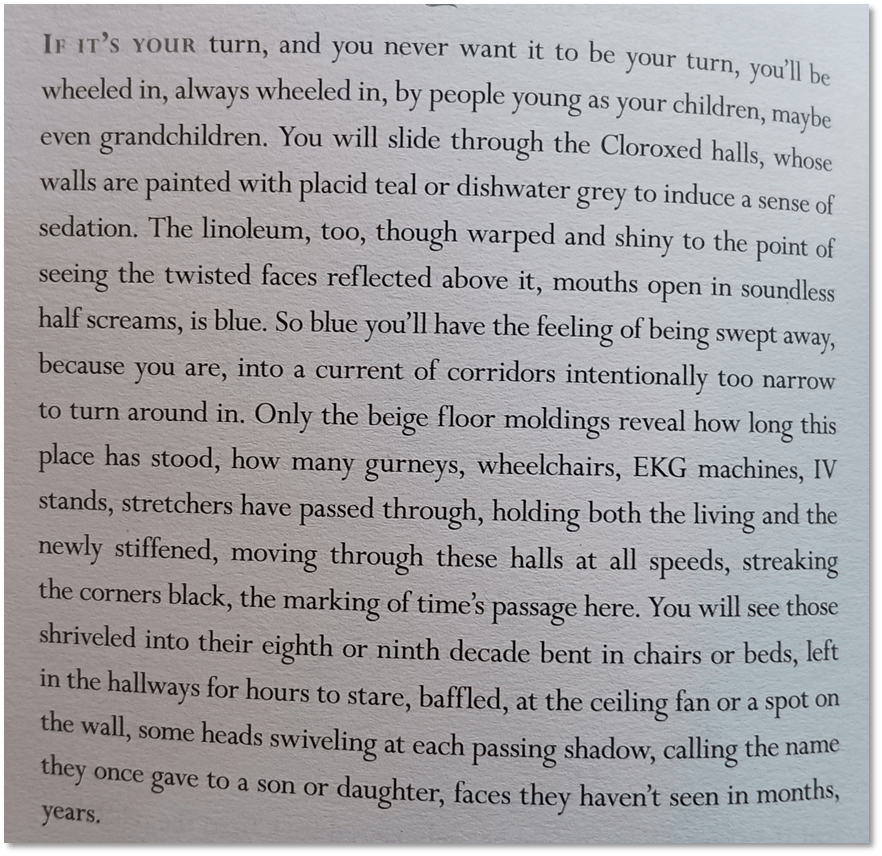

Grazina isa woman bound to fall – in one way or another, as her son Lucas insists. Though Hai thinks he may promise to redeem her, ensuring that “she won’t fall again”, Lucas responds like the world-weary: “Oh, she’ll fall again! That’s bound to happen”.[12] For mortality equates with falling, its outcomes apparently sounding like a ‘hellish mix’. This is the situation from which I take my title quotation. Taken to a care home where, as every social worker knows, ambulant frailty is just as likely to fall as at ‘home’, Vuong represents it as the final blocked path of the career that is a human life, deceptively painted sky-blue. The whole of the passage reads a passage from a Juvenal satire about the fate of age that will not accept its general fall, or like that English version of the Tenth Satire, Dr. Samuel Johnson’s The Vanity of Human Wishes, particularly this passage:

Enlarge my life with multitude of days,

In health, in sickness, thus the suppliant prays;

Hides from himself his state, and shuns to know

That life protracted is protracted woe.

Time hovers o’er, impatient to destroy,

And shuts up all the passages of joy:

In vain their gifts the bounteous seasons pour,

The fruit autumnal, and the vernal flower,

With listless eyes the dotard views the store,

He views, and wonders that they please no more;

Now pall the tasteless meats, and joyless wines,

And luxury with sighs her slave resigns.

Approach, ye minstrels, try the soothing strain,

And yield the tuneful lenitives of pain:

No sounds, alas! would touch th’ impervious ear,

Though dancing mountains witness’d Orpheus near;

Nor lute nor lyre his feeble pow’rs attend,

Nor sweeter music of a virtuous friend,

But everlasting dictates crowd his tongue,

Perversely grave, or positively wrong.

The still returning tale, and ling’ring jest,

Perplex the fawning niece and pamper’d guest;

While growing hopes scarce awe the gathering sneer,

And scarce a legacy can bribe to hear;

The watchful guests still hint the last offence,

The daughter’s petulance, the son’s expence,

Improve his heady rage with treach’rous skill,

And mould his passions till they make his will.

Unnumber’d maladies his joints invade,

Lay siege to life and press the dire blockade;

But unextinguish’d Av’rice still remains,

And dreaded losses aggravate his pains;

He turns, with anxious heart and crippled hands,

His bonds of debt, and mortgages of lands;

Or views his coffers with suspicious eyes,

Unlocks his gold, and counts it till he dies.

Compare the ethical timbre of that passage with this wondrous passage of two paragraphs of prose definitively in the empathetic moral tradition, but with a difficult lesson. It is the kind of thing we barely expect of the modern novel, let alone the modern queer novel. The issues of this novel cannot be the issues of a part of humanity, however needy of redress from negligence because life itself is unvalued – human, animal or vegetable. It requires a blessing in all its forgotten corners and a voice to say that blessing. And that voice is the redeemed novel of life’s beautiful meanings.

This is why the Emperor Hogs matter! M. John Harrison in The Guardian wrote of the novel that, in it, chosen family ‘outings include a visit to a slaughterhouse where the barbaric conditions are genuinely difficult to read’.[13] That’s is true but it is ‘genuinely difficult to read’ because it is yet another instance where the ethics of the commodification of good conscience in meat-eating, as one example of the processes that stand against life, is both exposed as a lie of capitalist production processes, together with their neglect of the life of ‘raw materials’ and ignorance of the motives of persons forced to turn to hog murdering as the only alternative to leaving their chosen family to bear the burden of the guilt of killing in order to equip themselves to eat and survive. Hai thinks, as he looks at the faces of the hogs lined up for massacre:

If Wayne hadn’t been counting on to get that bonus, Hai would’ve walked right down the road and hitchhiked back to East Gladness soon as he saw their faces. But what could he do? He was part of a team, and that meant something, didn’t it?[14]

Harrison thinks this is about ‘the brutality of work’, another theme he plucks from the novel, like that of the supreme value of the chosen family, but it is more than just another theme. It is meant to make its readers feel as well as think about the moral questions posed, and for me that works. Moreover, such thinking involves unpacking the myths that separate, say, animal from human life – the story of the Gadarene swine from the Bible, for instance, or of how the Emperor Hog got its name as refined foodstuff for powerful people – that turn life into commodities for exchange, even exchange across continents and over empty oceans. The novel ends with the scream of the hogs sacrificed to the greed of a Chinese Emperor, as if it were the sound of life falling to the common fate of death, like a river that passes the dead and dying that fall into it to a common mortal ‘home’:

And that’s when he heard it – not the river’s rush, but the hogs.

Dragged by their hooves into the emperor’s butchery, they were screaming from a galaxy far, far away, inside him. And they sounded like people.

Soft, simple people, who live only once.[15]

If the novel is a novel of what late eighteenth century British culture, and Adam Smith in particular, called moral sympathy – an early form of the more modern ‘empathy’, it is also continually unbearable for the screams we hear in it, under its glorious humour, are those of the regretful dying – whose lives were wasted and whom our world too soon calls ‘losers’. In this novel, we live only in communalism. Even simple Wayne knows that. He sees isolated trees as in deficit:

“my grandad told me when the trees stand on their own, with no other trees round them, their branches grow wild …. Branches twisted all over the place, like they’re trying to grab at everything and nothing’s around to hold us”.[16]

The people who might have been named social losers in this novel include a Vietnamese migrant boy with a learning difficulty like Sony orphaned by injustice and death, Maureen made ‘mad’ by her weird conspiracy theories that tell allegoric truths, Grazina lost in the turmoil of the past struggle of giants – Germany and Russia – to whom she, as a person not a state, did not matter. Losers are only so however when forced into an isolation by the powerful; for those our society denominates ‘losers’ can build chosen alliances and bonds that have a temporary power and render them into ‘makers’ not fodder to be eaten by the rich. Sony ‘s obsession with the American Southern confederacy of the Civil War – and its enslaving traditions – is not as ironic once we see it from his perspective and, as he sees a road into the future:

Sony grew quiet, looked away at the dim headlights trailing off on the highway. The song was over. “But we’re still losers. All of us. All we did was lose. Just like Robert F. Lee, my dad also lost his war in the South…”. …”We might be beautiful, but it doesn’t matter when we’re losers. …[17]

Entitled cultures turn whole nations into losers, as in the John Wayne film Green Berets, which compounds imperialist fact with the fictions the entitled need to tell themselves.[18] The point of this novel is to find a way of retelling ‘history’ (about which it has a lot to say including how history is fictionalised in cultural institutions – like the Stonewall Jackson museum where ‘history is fun’) from the perspective of the desire of losers to solidify their moments of redeeming community – in chosen families (even ones based in work teams) or in memories that make lost lives matter again. This is the role of ‘poesy’ in Sidney. The critics of our major newspapers so often fail to read with honour to the beauty it reveals. M John Harrison for instance notes the beauty of this novel’s introduction but sees it merely as a chance for Vuong to ensure that his ‘poetic credentials’ are established before he ‘gives narrative its head’.[19] But that is cynical in truth. It takes as its main motif – not ‘theme’ mind – the central cultural value of food, and its relation to universals of home and community– the poetic in this novel always lurks under its narrative fictions that verge on the symbolic or complex allegoric, and the struggle by which we stop ourselves becoming ONLY food to processes that force us to be losers – like Emperor Hogs.

Wrapping arond the tent’s perimeter was a rust-thick chain-link that prevented hogs from bolting once they realised they were doomed for the chandeliered dinner tables of millionaires. The plastic sign, zip-tied to tje chain-link, read MURPHY’S FREE-RANGE PORK – A FAMILY FARM SINCE 1921. [20]

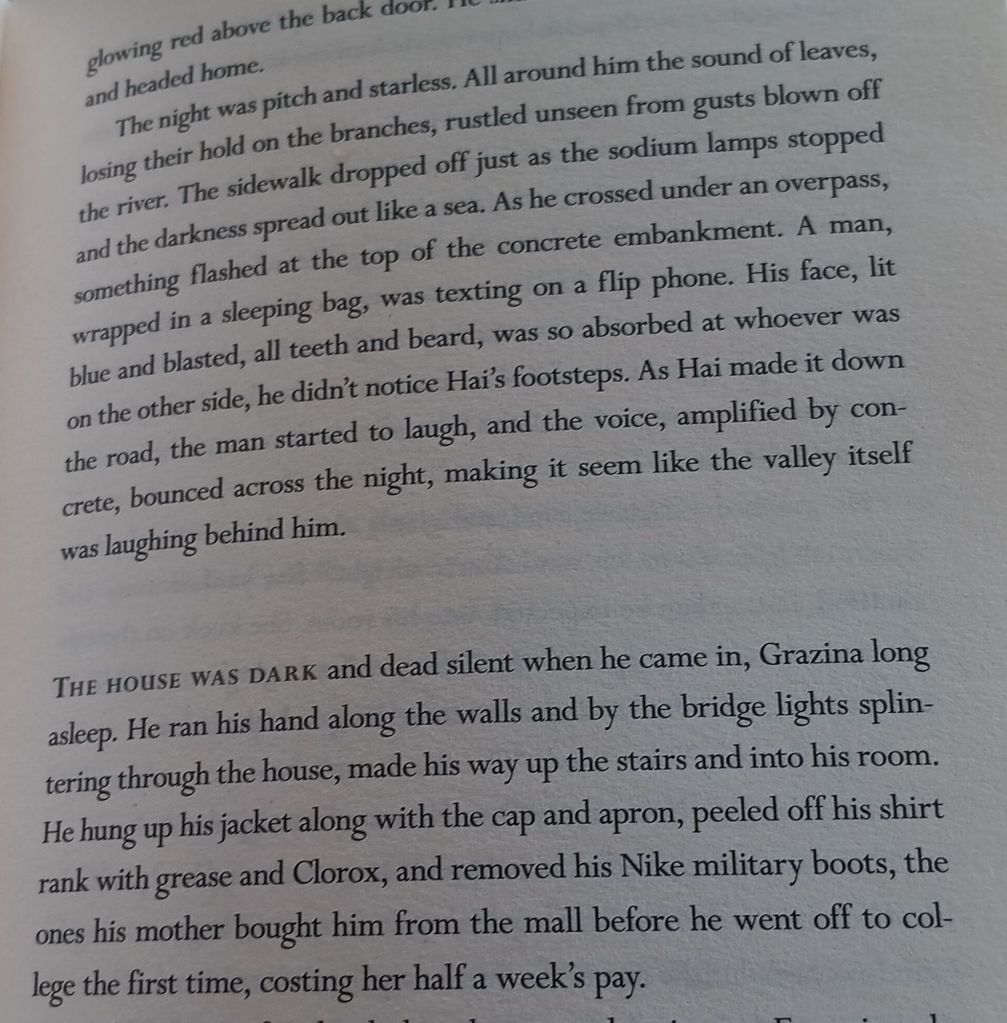

Underneath the humour-full tough love that regulates this novel’ satire, sometimes heavily applied, are songs sung by the oppressed and the supposed losers. Take, for instance, that moment when Hai believes that, despite her protestations that she can’t sing, he hears Gazina’s version of ‘Silent Night‘ in a ‘beautiful voice’. [21] We hear the lyric too under the prose. Take this moment. It is a resonant and extended Silent [and Dark] Night.: [22]

All for now.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Ocean Vuong (2025: 310) The Emperor of Gladness London, Jonathan Cape

[2] Ibid: 397

[3] See Sir Philip Sidney | The Poetry Foundation at https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/philip-sidney

[4] See Ocean Vuong (2025: 5, 29, 34, 69, 181) The Emperor of Gladness London, Jonathan Cape

[5] See ibid: 67, 285

[6] Ibid: 8

[7] Ibid: 108f.

[8] Ibid:124f.

[9] Ibid: 34f.

[10] Ibid: 369

[11] Ibid: 31

[12] Ibid: 309

[13] M. John Harrison (2025) ‘American Dreams’ in The Guardian Supplement (Saturday 17th May 2025), page 49

[14] Ocean Vuong 2025 op.cit: 207

[15] See ibid: 207 & 397 respectively.

[16] Ibid: 205

[17] Ibid: 231

[18] Ibid: 321

[19] M John Harrison, op.cit.

[20] Ocean Vuong 2025 op.cit: 198

[21] ibid: 21

[22] ibid: 101

A beautiful tender hearted novel with two unforgettable characters and a supporting cast of equally life affirming minor characters. Brilliant.

LikeLike