If Édouard Louis were to answer this question, he would date his age and that of his parents not in conventional space or time but in the never-to-be-ended phenomenon of the ‘escape’ of each from the determination of the other, should that ever be possible. This is a blog on Édouard Louis (2024) ‘Monique Escapes’ (trans. John Lambert, 2026).London, Harvill, Vintage.

Many bilingual dictionaries insist that ‘s’evade’, used in the 2024 French title of Édouard Louis’ latest book on the transformations in and between the networks of his family, is literally the equivalent of the English word ‘escapes’. My French is too poor to argue though I would think that there might be a reason that that he employs a verb not so demanding of a transitive subject as échapper. No doubt I get muddled in my amateurish French, however. Nevertheless I think it is important that that there is something existential in the idea of Monique ‘Escaping’ more than one circumstance or situation that might bind and contain her, the very thing Louis believes he does for himself in Changer: méthode (2021) (Change (2024) but literally ‘To Change: Method’). I blogged on the later book – read it at this link.

Monique Escapes is a rather less appealing book than Change, in my view, for it begins to elevate Louis from the narrator as self-make-destroyer- re-maker (in a continuing cycle) to the narrator as facilitator in the autonomous change of others, notably his mother, Monique. It is a process he began, he says, in his book in the earlier A Woman’s Battles and Transformations . This book ends, if it can ‘end’; without falling into the teleological trap I spoke about regarding Change, with Monique having attended a play in German based on that book by her son, and gaining pre-eminence, of a performative kind only of course, over everyone including her son’s writing. In the final short section (III), she finds a copy of that book on her son’s bookshelves, and succeeds in demanding (in effect rather than in obedience to command – for that would be too compromising for Louis – that Louis shift his attention from a book he is writing on the death of his older brother from alcohol:

“I’ve changed a lot again since you wrote this book. You’ll have to write that one day! I’ve changed again,”

I told her she was right.

“It’s true. It’s true. And I will.”

I long to look at the original French here, for that ‘I will’ is crucial, for it is as if Monique herself has shifted from seeing her son as the recorder, and perhaps – because this is literary writing – ‘shaper’ of her metamorphoses into being the agent of it HERSELF: ‘I will’, not ‘You will write it thus’, or words to that effect. Nevertheless, when Louis explains that he puts aside his account of his brother ‘to write this new chapter of my mother’s life, of her metamorphoses’, he says:

Through her, I’ve discovered the pleasure of writing in the service of someone else. [1]

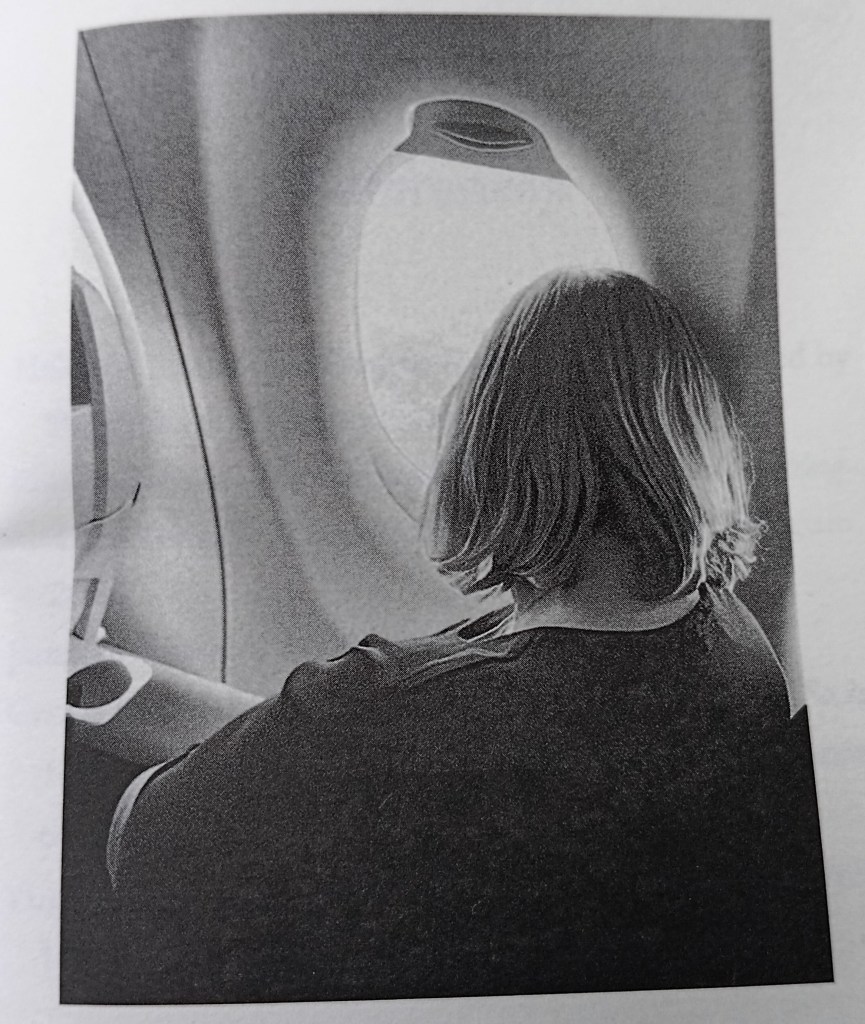

That seems ‘right sneaky’ (my Yorkshire wins through here) of Louis here, for though he writes Monique saying ‘I will’, it is only his will that makes the book happen, in the appearance of ‘service of someone else’. Ultimately, the book is his, though he tries so hard to make it hers since, ‘I wasn’t the first one to get the idea’. It gives him enough joy this seeming service to another that when we turn the page we see a photograph of the real Monique, but from the back sitting at the window of her first airplane flight (a story told in Section II) on the way to a play about her written from her son’s globally famous text. It is as if she is flying away so that Louis can plot his own metamorphoses again in the next book -on his brother, a subject who conveniently dies, leaving Louis alone on the field of those working for their emergence in the long duration of his future writing career.

This is a beautiful book. It again treads those difficult ideas about change being the result of the necessity of endured violence, and the wreaking of revenge by heroic self-transformation on those who put you down in the past, and hence will be crucial to fully understanding Édouard Louis’ oeuvre, once we have it in toto, when that is he is dead or has stopped writing forever (perhaps seen as the same phenomenon). Nevertheless, it is a book that serves really, not Monique, but Louis the writer, showing he can do for others, even those who hurt him in the past, what he does more effectively for himself.

There is a sense in which Louis can only be a reliable theorist of the underlying violence of gendered heteronormative class society because as a narrator and perhaps as the character in a novel, he is unreliable. One sense continually the artist struggling and battling to be larger than his subject because of the importance of the impersonal truths that he needs to share with us. I sense that where he creates an aside where he shows that even Virginia Woolf, the stereotype for some of aesthetician, ‘answers a literary question with financial and material concerns’, almost as if she too knew Marxism from the inside of the capitalist beast he, and she, describes [2].

This is a book, he says in continuation, trying to do what earlier books had done, trying ‘to introduce money in the strictest and most explicit sense’, as well as a theory of value. And then he adds another point: ‘the story I’m telling is not a homage to escape‘. His continuing elaboration shows that it is not either truly about a ‘brave woman’, his mother but about inequality and oppression: ‘How many sacrificed lives are there for each life saved?’ [3]

It is because that is the case that, once Monigue has escaped, we need to see that whixh she ostensibly escaped, the person she calls ‘The Guy’, was an.even more insignificant person than his father, another belittled victim of capital and oppression. When his mother resists The Guy, sees something other than the Guy himself driving that ‘puny and insignificant little being’:

he himself had been an element through which violence had passed that was bigger than him and not easily explained, the violence of hus upbringing ginger the violence of his social classes, the violence of living in a relationship, the violence of male domination. [4]

In brief, this ‘weak and pathetic looking man’ was no more than a vehicle through which that story, usually seen as little more that theory, and hence not unlike Eddy in ‘The End of Eddy’ or any of his family members become novel characters.

So much is that the case, that in the very brief Part III of the book, Monique has transformed again in and through Louis’ wroting.’Seeing her brave out the firsttruggles of her present self, having revenged herself on those who once hurt her by seeing them as no longer of import to her or anyone, she is merely ‘a woman who made ne laugh’. A subsection of Part III ends here with a small star [*] symbol. The next subsection starts: ‘She’s no longer my mother’.. [5]

Is it hubris in a writer that he can determine, not only the stimuli that is his material into characters and events in a plot, but also large and significant changes in their inter-relationship, even when these have a symbolic value in conventional life? Perhaps it is! However, it is okay for the character called Édouard Louis to be unreliable as narrator and character because he too is material through which latger themes are both conceived as ideas and illustrated by Édouard Louis, the socialist artist and theorist of art and society. That is why I title this blog with the following question: If Édouard Louis were to answer this question, he would date his age and that of his parents not in conventional space or time but in the never-to-be-ended phenomenon of the ‘escape’ of each from the determination of the other, should that ever be possible. For the story that Louis tells his never-ending, though as time passes, he continually needs to recycle material from his past whose significance can develop further the story he is telling: the history of class violence, now in its most vicious high capitalist stage.

He summarises this epic story which belittles all its characters and other actors in a conversation with Ken Loach, in a passage I quoted in my blog on Change, (with a link above).

Appartenir à une certaine catégorie sociale et politique, c’est, de fait, être exposé ou non à une mort prématurée. On sait qu’un ouvrier en France a deux fois plus de chance de mourir avant 65 ans qu’un cadre, que les personnes LGBT se suicident beaucoup plus que les autres, que des femmes meurent chaque jour de la violence masculine… Il n’y a sans doute rien de plus efficace pour saisir le fonctionnement du monde que de tenir la comptabilité des morts. Le plus étonnant, c’est qu’en effet, celles et ceux qui gouvernent savent ces choses-là, on ne peut pas l’ignorer. Tout le monde sait que les ouvriers vivent dans des conditions difficiles, tout le monde sait que la domination masculine existe ou que les Noirs et les Arabes en France sont très majoritairement assignés à la pauvreté, aux banlieues, à la précarité, aux violences policières.[6]

It’s a passage he says could describe Loach’s I, Daniel Blake too . In this grand epic, the victims of une mort prématurée include LGBT+ people, women from male violence (hence Monique too), or minority Black and Arab people in France exposed to poverty and the violent policy-making of an oppressive state. Since the story is so much larger in scale and endlessly repetitive of one huge behemoth of structured oppression, devouring the lives of the vulnerable, why ask what were one’s parents doing at one’s age. They were lucky if they were merely escaping (or evading, being one’s parents, another’s wife or something’s employee or the state’s ‘lumpen burden’, as that monster sees its victims.

Fortunately people are not mere victims of this system. Eddy was and had to meet his end, and become Édouard the queer socialist hero and writer, just as Monique only becomes that name each time she progressively frees herself from male dominance, though clearly his older brother was not so lucky – alcohol is possibly the sternest tool for the dispatch of those who can never be ought but victims, for it ties down the will to change to the mechanism that make finding that will very difficult even without alcohol’s lies about a possible happiness in the status quo.

So there’s my answer. My father and mother both died at an age some ten years from where I am now, broken by lives of uneasy toil and desires imposed by the capitalist machine, aided by state services inadequate to the task of a true distributive state. I expect I will end as they – and maybe in shorter time than ten years.

All for now, with love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

__________________________________

[1] Édouard Louis ((trans. John Lambert, 2026: 117) ‘Monique Escapes’ .London, Harvill, Vintage.

[2] ibid: 76f.

[3] ibid: 78

[4] ibid: 84f.

[5] ibid: 97.

[6] Louis in Ken Loach & Édouard Louis (2021: 13 of 67) Dialogue sur l’art et la politique Paris, Presses Universitaires de France / Humensis, ascited in my blog (f.n. 8) https://livesteven.com/2024/02/19/this-is-a-blog-on-edouard-louis-changer-methode-2021-change-2024-but-literally-to-change-method/