In reading this question, the contemporary and most frequent use of the word ‘complaint’ will be uppermost, which is mainly related to an expression of grievance or satisfaction leading to seeking a means of redress from the person or institution providing those goods or services which are found faulty or dangerous. It is part of an active process. Yet etymologically a complaint need not lead to seeking redress but is expressed precisely because one is powerless to change the situation that is the subject of the complaint, and cause of present suffering. A complaint may seek relief from the expression of this hopeless situation but not by changing it, as if expression would in some magical way make one feel better.

The ‘sense evolution’ in the word is historical and part of the word’s etymology, as expressed below by etymology.com.

complain (verb.): late 14c., compleinen, “lament, bewail, grieve,” also “find fault, express dissatisfaction, criticize,” also “make a formal accusation or charge to an authority,” from stem of Old French complaindre “to lament” (12c.), from Vulgar Latin *complangere, originally “to beat the breast,” from Latin com-, here perhaps an intensive prefix (see com-), + plangere “to strike, beat the breast” (from PIE root *plak- (2) “to strike”). / The sense evolution is from “expression of suffering” to “grievance; blame.” The transitive sense of “lament” died out 17c. Also from late 14c. as “utter expressions of grief or pain,” hence, chiefly poetically “emit a mournful sound” (1690s).

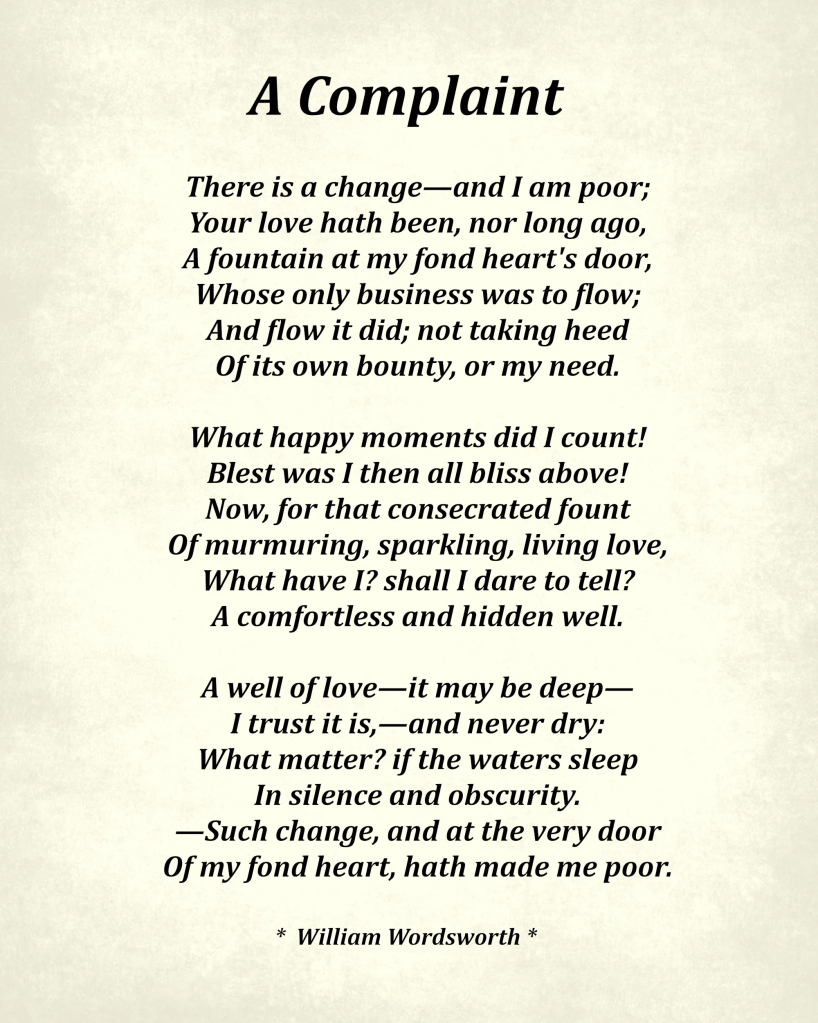

It is wise to read this carefully, for it exempts the use of the term in poetry from the statement that the ‘ transitive sense of “lament” died out 17c.’, for in poetry, it did not. We find it in Wordsworth poem A Complaint of 1807.

Wordsworth’s poem follows the tradition from medieval and Renaissance poetry, that Encyclopedia Brittanica explains thus, with links in thevquotation to the European poets it mentions, for as with most things the tradition was European and descended from Greek and Latin poetic practice:

complaint, in literature, a formerly popular variety of poem that laments or protests unrequited love or tells of personal misfortune, misery, or injustice. Works of this type include Rutebeuf’s La Complainte Rutebeuf (late 13th century) and Pierre de Ronsard’s “Complainte contre fortune” (1559).

The speaker in Wordsworth’s lyric complains his lot by rendering it in imagery of a stagnant well, stagnant because no fountain feeds into it now and neither do its waters now appear to move on from its own static depth. Oddly being without love is like being cast into ‘silence and obscurity’ and being ‘poor (by which the meaning of being in poverty’ seems to be attached, as if it is the flow of cash that seems too to have stopped for the now poor person). The poem is a ‘Poor Me’ poem, for it lays all personal fortune on external forces, not the resolution and independence, the later Wordsworth valued and which made him say later, in the poem Resolution and Independence, that we can should only reliance on ourselves for shelter, food and love, because ‘needful things’ do not ‘;come unsought’.

My whole life I have lived in pleasant thought,

As if life's business were a summer mood;

As if all needful things would come unsought

To genial faith, still rich in genial good;

But how can He expect that others should

Build for him, sow for him, and at his call

Love him, who for himself will take no heed at all?

I thought of Chatterton, the marvellous Boy,

The sleepless Soul that perished in his pride;

Notice the reference to Chatterton, who died because of dependence on a patron. Hence, I suspect that there is irony in this poem, some sense that the speaker(even if a poet) is responsible for his own poverty, silence, and lovelessness, too ready to grieve rather than to move on by some source of dynamism that comes from within themselves rather than without. If I am correct about this, Wordsworth is in the poem, implicitly critical of the kind of sensibility that uses all its energy and resources to complain of its lot, seeing the agencies of change as entirely external instead of rousing itself to bring about change from within and mobilising change’s reflection in the external world, although latterly only in a quiescent way, not the revolutionary radicalism of his youth, for Wordsworth had become a Tory accepting state and other patronage, that he had earlier renounced vehemently.

There is no doubt that a culture of individualism is intrinsically antagonistic to the activity of complaint about one’s lot, rightly or wrongly. , since it moves the stress on responsibility to self to external factors – a lady who does not love you as you do her, or Fate, Fortune, oft a lady too in those poems.

In medieval.poetry, too, there can, however, be the same hint of irony, for a different reason – for sometimes you do not want to address the external forces that might fund you too directly, and medieval poets had no choice but to accept patronage. Let’s take Chaucer’s poem: The Complaint of Chaucer to His Purse (as it is known in the Collected editions. Framed initially as a ‘complaint’ poem literally to his own purse in question, its purpose was, in fact ‘ to persuade King Henry IV (1367-1413) to renew the poet’s annuity’. I take the text from Carol Rumen’s republication in The Guardian in 2009 (https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2009/feb/02/complaint-chaucer-purse-poetry) because it reproduces Kathryn Lynch’s schol;arly text and helpful glossary to Middle English words.

The Complaint of Chaucer to his Purse

To yow, my purse, and to noon other wight

Complaine I, for ye be my lady dere.

I am so sory now that ye be light,

For certes but if ye make me hevy chere,

Me were as leef be leyd upon my bere,

For which unto your mercy thus I crye

Beth hevy ageyn or elles mot I dye.

Now voucheth-sauf this day er it be night

That I of yow the blisful soun may here,

Or see your colour lyke the sonne bright

That of yelownesse hadde never pere.

Ye be my lyf, ye be myn hertes stere,

Quene of comfort and of good companye,

Beth hevy ageyn or elles mot I dye.

Now purse that been to me my lyves lyght

And saveour as doun in this worlde here

Out of this toune help me thurgh your might

Sin that ye wole nat been my tresorere

For I am shave as nye as any frere;

But yet I prey unto your curtesye,

Beth hevy ageyn or elles mot I dye.

Lenvoy de Chaucer

O conquerour of Brutes Albyoun

Which that by line and free eleccioun

Been verray king, this song to yow I sende,

And ye that mowen alle oure harmes amende

Have minde upon my supplicacioun.

Abridged glossary

"Me were as leef" = "I'd just as soon"

Pere = peer, equal

Stere = rudder

Toune = town, "probably Westminster, where Chaucer had taken refuge (perhaps from his creditors) in a house in the abbey grounds." (KLL).

Tresorere = treasurer

Frere = friar (Chaucer is saying that he has as little money as a tonsured friar has hair).

Mowen = May

The only irony is not that, like Wordsworth, Chaucer is critical of anyone accepting that real agency for change and security lies external to him, in a king or patron – the poem is written on the death of his patron the onld king Richard II, to the new one, Henry IV. As Carol Rumens says, the envoy of the poem grossly flatters Henry, reading his winning of the war to every right that king might claim, comparing him to Brutus (as kings who won thrones by force did – witness later Henry VII). Hear it well said by Rumens:

It’s in the envoi (“Lenvoy de Chaucer”) that the poem acquires a more solid, earnest tone. Chaucer seems to want to display his learning, perhaps as a sound basis for his flattery. Directly addressing the King, he praises him as the descendent of Brutus (legendary founder of Britain), and rightful and true (“verray”) occupant of the throne. “Have minde upon (consider) my supplicacioun” is the humble final plea. It’s as if the poet had dropped to his knee and bowed his head. The joke’s over, he really needs the dosh. Most of us can sympathise with that at the present time, can’t we? Happily for Chaucer, his Complaint did the trick.

I am not sure we do like the kind of suppliant dependency of the medieval feudal world as much as Rumens suggests, but we are hardly as blatantly able to be cynical about it either, as Wordsworth is – pointing us to a poverty stricken Leech-Gatherer who is, Wordsworth claims, at least self-reliant, having to sell only what he can find in inclement and unpleasant conditions of nature (he only gathers leeches, does not – like leeches – suck the blood of others). And even Chaucer before the envoy, complains not to the King, or about him, but another lady who is ‘light’; the word is resonant with multiple meanings, his lady is accused of promiscuity in leaving him with ‘hevy chere’ (depressed facial features and mood) instead of being the light of his life, where to be light illuminates and saves (even redeems is suggested here) and adds to him and does not take things away. It is okay to look at the perfidy of Fate and Lady Fortune, but not to blame the king for deposing Richard II. Chaucer is selling himself to Henry as a patron-dependent poet must unless he is to die in the same kind of poverty Wordsworth describes (Me were as leef be leyd upon my bere _-I might as well be laid out on my funeral bed).

I cannot say I do not complain in the old sense – most of us know that it is therapeutic to look for empathy, if not sympathy – but I try not to. Nevertheless, I think sometimes our culture of complaint is itself less about complaining to put things right as a demonstration of helplessness. What we don’t see is that some forces external to us like us to feel helpless, and see our redemption in them. This currently is the Reform Party, a mass of complaint with solutions they won’t share, for inf they succeed these solutions will be imposed on us and everyone. One need only look to the United States to see how this will happen.

All for now.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxx