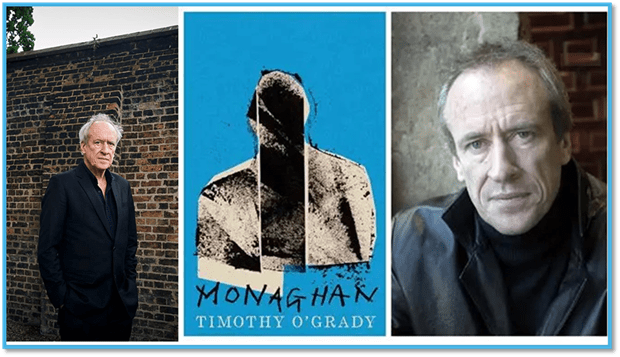

You get to build your perfect space for reading and writing. What’s it like? I think that for me the only answer I could supply would be that I should build a space that breaks down the boundaries we build around us to define our interior. Talking about his inspiration in writing To Anthony Cummins in The Observer Timothy O’Grady tells a story where he is praised by his peers, if not those who consider themselves his superiors and teachers for saying what they ‘feel too’ bur dare not say so. He concludes: “To articulate something in somebody else’s head was very exciting”.[1] I wondered to myself whether this is what Timothy O’Grady achieves in his 2025 novel Monaghan. If so that is my ‘perfect space’ for ‘reading and writing’ – where interior spaces meet no boundaries and are, therefore both the inside and outside of the space holding reader and writer simultaneously.

Talking to Anthony Cummins in July this year, before the publication of Monaghan, Timothy O’Grady answered Cummin’s query about the fact that that novel ‘intertwines three men’s stories. What drew you to that structure?’ O’Grady’s answer involves a surprising take on the novel, which previously he had described as aimed at getting inside the mind of a sniper for the IRA. This answer instead claims that the novel is itself about undermining the contemporary trend for writers to build their ‘perfect space’ for writing and reading in a university ‘creative-writing’ department:

All my fiction has been first-person but I couldn’t see that Ryan [the sniper] would tell his own story because it would seem to him like a vanity to do that. So I started writing in the third person but I couldn’t even get him to cross the street; I needed an “I” somewhere, and that’s where Ronan [the narrator] came in. I’d had a bit of experience of academic life, seeing creative writing programmes taught by the most risk-averse people you’d ever meet, which isn’t necessarily inspiring for students. The book is about that as much as anything. Whatever choices Ryan made, he put himself on the line, which Ronan can’t bear – he feels a fraud.[2]

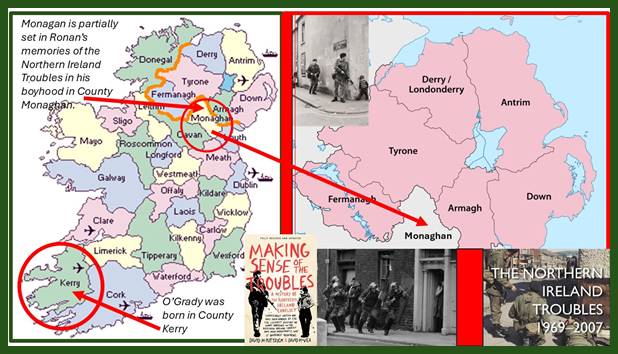

Ronan is not a teacher of creative writing but he is an academic – of architectural theory and practice (a space-shaper therefore) – committed to reading and writing about architecture (building it only virtually in books mediating thoughts, feelings and acts of building that speak of architecture while not being it in terms of building spaces for living, working and playing in a real space-time that is inhabited by communities of people. Only in the latter kind of building is taking risks a necessity of actual practice. Nevertheless, though it is tempting to see Ryan (who is an artist as well as a paramilitary sniper) as a kind of type of Irish life during the struggles in the North between the British army and Protestant paramilitaries on the one hand and Catholic paramilitaries on the other, O’Grady makes it clear that his Kerry upbringing in the extreme South of the Republic put him at considerable distance from the life of a boy, and man, like Ryan, and any familial proximity to paramilitary action and its consequences in his own boyhood in Monaghan on the very border of the Troubles and ideal for armament storage.

What matters to him more is his learned acquaintance with those people and their heirs in Donegal, where he researched the novel with past IRA members and others who lived through a time which justified the killing of ‘enemies’ to their struggle and live with its aftermath still.

However, the frameworking of Ryan’s novel though Ronan, and a contrast with another character, Paul Crane, a man who (like Ronan) becomes obsessed with Ryan for multiple reasons which are hard to disentangle but not the same as Ronan’s equally complex bonds to this beautiful young man is clearly more than a device to make Ryan more authentic as a man who would not tell the tale of his life-experience in his own voice.

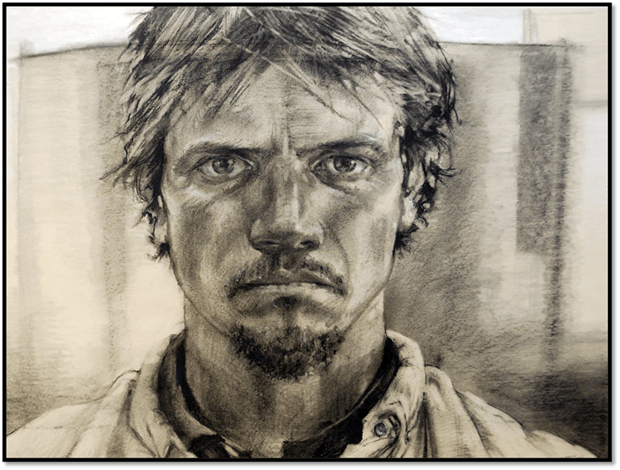

Ryan’s self-portrait by Anthony Lott: ‘the man who caused my downfall’[3]

Paul’s obsession, however, is not least concerned with what the cost was of Ryan’s integrity as an artist and man working in his service It also serves to carry further O’Grady’s convictions about the space that a writer and reader should occupy – a theme too of his earlier great novel, his second written in 1997, I Could Read The Sky. It is a theme he attributes to John Berger, who also wrote the famous preface to the latter. In the Cummins interview, he traces to reading Berger’s G, his interest in reconfiguring the space in which one writes from one occupied predominantly by cognition to one defined instead by access to ‘deep feeling’.

It’s easier to talk about something clever than something with deep feeling, and when I was a student it was a time of experimental fiction: John Barth, Donald Barthelme. Part of what broke through my interest in cleverness was John Berger’s G, which didn’t feel like the kind of thing American experimentalists were doing. It seemed a genuine effort to break through the page, like he’s just sitting across from you, talking, instead of you being in the audience, dazzled.

What is noteworthy here is precisely the establishment of a reconfigured space in which reader and writer sit face-to-face unobstructed as far as possible by the ‘page’ that mediates their relationship, and where intellectualisation offers no defence from emotional immersion and sharing uncomfortable truths. Intellectualisation was recognised by Freud as a primary psychological defence structure from feelings that make the ego uncomfortable. Hence it’s need to bolster itself up psychosocially with conventions about propriety in communication and a hierarchically configured structure of barriers to feeling. The latter structure (often in a personal hierarchy) likes to think itself unshakeable, despite the overt need to showily over-defend itself, and an army of roles in differing domains to represent those defences such as priests, teachers and counsellors that deflect the ego from discomfort and ‘triggers’ to truthful but disruptive reflections of itself. I took my title quotation from this recollection by O’Grady in the interview cited above:

I went to a Catholic high school taught by Jesuits, where we were square: our clothes ironed, headed for some kind of middle-class life. Like a Rolling Stone came on the radio one day as I was being driven to school and I heard for the first time Dylan’s thrill in writing it, evident in the way he sang. Later, this priest was giving us essay assignments and I thought: this time I’m just gonna say what I think, and so I wrote this screed about the hypocrisy of the older generation. When I took it into class, the priest told us: “From today, every time you do one of these essays, I’ll ask someone to come up to the front and read it aloud; we’ll start with Mr O’Grady.” He hated it! But as I was leaving the class, these two guys I didn’t know very well said: “That’s how we feel too.” To articulate something in somebody else’s head was very exciting.

The material in Monaghan owes a great deal to his research from for his 1982 co-authored work, Curious Journey: An Oral History of Ireland’s Unfinished Revolution. Cummins describes it ( I haven’t read it) as ‘a collaboration with the late documentarist Kenneth Griffith, which gave a first-hand account of Ireland’s civil war through interviews with veterans’, and its themes of the disturbance of surface structures aimed at disturbing a settled psyche ready to displace or repress anything that challenges its over-achieved current state of ‘balance’. In the novel’s articulations of violence, that violence (observed or acted) is mainly located in the memory as O’Grady tells Cummins:

I was intrigued by the effect of violence on the psyche. I asked various people in the IRA what it’s like to kill someone and they all said the same thing: that you can’t go back to who you were. I know the victims wouldn’t worry about that [but] it’s not my position to give an opinion about rightness or wrongness. The book just tries to get inside [the sniper’s] head. What mainly interested me was not the war but the aftermath. British soldiers, cops, IRA members, loyalists: they’re all walking around with that. What do they do with it?

However, though this certainly also describes the underlying violence, usually in terms of violence to animals but also in repressed memories of the Civil War before the birth of the Irish Republic, in I Could Read the Sky, in Monaghan this balance is that too of fantastical feats. In Lott’s imaginings these characterise the circus, the below image being a realisation of a line drawing in the book:

(mixed media on paper) from: Monaghan – ANTHONY LOTT , https://www.anthonylott.studio/monaghan.html

They are symbolised in the narrative too by Nicky a high-wire performer, with whom Ryan falls in love, in her circus life. In the story her life is disrupted when she sees her circus colleague and friend fall to his death – leading to her meeting Ryan in a bar as she applies alcohol to the distress that fall opens up in her.

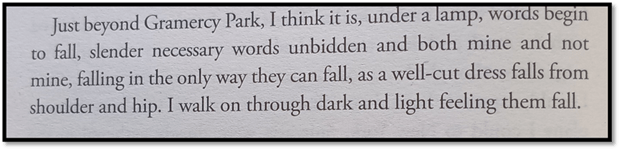

However, there are many things which ‘fall’ in this book (literally and metaphorically), even unbidden words from one’s own past story in its involuntary telling or from unacted desires. In this book, and in the quotation below, this is represented by dresses which men fantasise about as ready to fit them as they also fall off them. The book opens with an in media res reflection from Ronan as his family life is falling apart over his fascination with the remarkably beautiful and intriguing Ryan, an event yet to be told in the sequence of events from the beginning, and which start in the succeeding chapter. Fleeing from the empty flat in which his wife and daughter leave him behind, he walks, heedless of time and other notions that structure life, feeling that ‘the density of things has changed’.

Timothy O’Grady ( 2025: 4) ‘Monaghan’, Barleythorpe, Rutland, Unbound Books

What disturbs here is not violent killing, or other means of death or injury; it is the soft, slender but visceral feel of a dress falling from a man’s body at two points where the senses imagine they may feel it most as a woman that provokes the words that are the confessional structure of Ronan’s first-person narrative role in the novel. Ryan is a complicated figure – a man whose life will require him to have many roles and names (and passports) to identify them. He is the hard man we assume a ‘sniper’ might be, however, he is also from the first a particularly haunted artist, capable of images that haunt others like Ronan here – not least a whole series of dresses associated with women that seem to live as if embodied without any human inside them.

The illustrator of the novel Anthony Lott used this theme in his book illustrations and in oil on canvas paintings that extrapolate from the novel’s imagery and iconography and are available on his webpage for the novel, referred to in the book’s opening publisher’s data. See this one, for instance from the webpage devoted to the novel. It haunts, though more harshly than the image in words above and other illustrations in the book itself in the illustration below in which a shield-faced naked male figure hides unsuccessfully behind a dress filled with the largely invisible body of a woman replete with female breasts and hips:

Bridesmaid II: (oil on canvas) from: Monaghan – ANTHONY LOTT , https://www.anthonylott.studio/monaghan.html

There is no doubt that these images are inside the-artist-who-is-also-a-sniper’s head, realised only in painting and drawing – many shared in the book in places where it is not always easy to relate them to text, but also, often with different associations introjected by viewers of his painting and drawing, such as Ronan and Paul. In truth we don’t even know his name, although at one time we are told that at ‘that time, he was known as Ryan’, and indeed is known as this through most of the novel.[4] At another time earlier we are told that he ‘entered the time when he had many names’ and that his ‘own became an oddity to him’, but we don’t for certain hear that ‘own’ name.[5] They don’t relate to the world of violence of the hard man ‘sniper’ Ryan sometimes is and even this role is scarcely ‘hard’ in the sense of being only about a world that is entirely physical in its being. In the role of Francis (one of his many names), he learns his trade and applies it but it lives mainly in acts of intellectualisation and plastic imagination:

The war was louder now and more populous. It moved with a momentum which he had in part created but which seemed always to be about to move beyond his reach. It was of wits, technology, terrain and morale. Pictures were made in the mind, the obstacles to their realisation assessed. The war’s acts were acts of the imagination. Aborted acts outpaced realised ones by a factor of fifteen. …

The war became for him like a sea, encompassing, heavy, ceaselessly moving. Its compass points were calculations and adrenaline, its tone monochrome.[6]

It’s difficult not to this ever-recreated man’s ever-recreated war as like the action of a novelist writing a novel in which mental acts have to be somehow realised, to be absorbed – at least the ones that get beyond their mental representation onto the page so that they might be again re-imagined in the mind of a reader. Indeed, when Cummins asks O’Grady if he prefers writing fiction to non-fiction, what he says recalls Ryan’s experience of war: ‘Eighty per cent of the time, writing a novel you feel pretty miserable. … Fiction is always dying in front of your eyes; even if you write one sentence, it’s impossible to know if you can write the next’. It even recalls his reasons for preferring Chekhov to many great storytellers because he is ‘both pitiless and compassionate’, like a war strategist as well as a man of deep feeling and ability to imagine the being of many people (and animals): ‘able to write with equal understanding about soldiers or aristocrats or dogs or children’.[7]

If ‘Ryan’ is an artist, and a constructor of narratives and character, and Paul Crane a reader and follower of patterns set by others (none of which he makes his own, , Ronan is an architect of ideal space, or at least sets out to be, modelling himself on Le Corbusier’s quest for ‘the miracle of ineffable space’, where the hands that realise a spatial design are ‘hands where could be read his anxiety, his disappointments and his hope’.[8] In fact those ambitions and pathways descend into mere intellectual academicism in which his hands make nothing other than writing of a severely abstracted and unemotive kind – theory divorced from practice and risk of implementation: ‘I had become a Theorist, first and last. I would never make a beautiful thing’.[9]

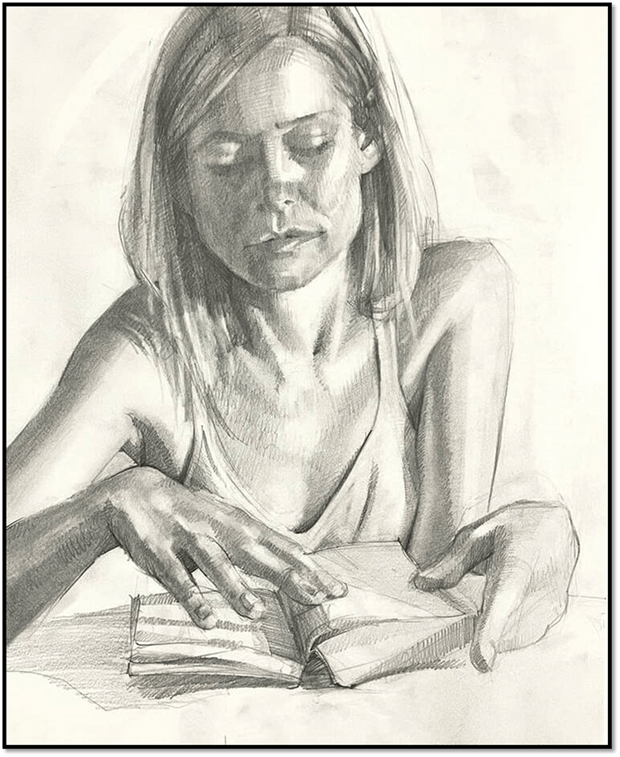

These three men, all of whom are also either able to identify with and make themselves women of a kind, either as an act of desire for another man or as a construct of an object of desire for themselves are makers of ideal spaces for reading and writing. Anthony Lott provides Ryan’s drawing for instance of Nicky, the circus-performer reading.

It is a reading that demands to be both read and written itself, or painted of course. When Ryan takes Nicky away from the circus, they travel the states:

Along the way he asked her what she saw, the colours, the shapes, the proportions, and what they made her feel. Did you see the rose, the green? What was the texture? She framed the scenes, she looked in the particular, she read what they made happen in her. They made paintings of what they said and heard from each other and when they got back to the city he painted them.[10] [my bolding]

The puzzle of this novel still to me is that it is an obscure answer to our prompt question about constructing an ideal space in which to read and write (or see images and paint them) and cannot answer it but by evoking infinite and many s[paces, that recollect each other – as Ryan’s French home where Ronan spends one night recalls Monaghan – but also do not, are radically different from each other. They are spaces both real and imaginary – made so by artists working on their externals and internals – have insides and outsides that sometimes are indistinguishable but which evoke deep emotion, that cannot always be read precisely – as Paul Crane likes to read things precisely as if they were patterns of numbers. They exist as creations of the mind and as things wanting access to the mind or egress from mind to realisation, but often in difficult balance with all these requirements.

I have read (or re-read – I have had the first edition for many years mainly for the Berger introduction) I Could Read the Sky and Berger’s introduction and ordered O’Grady’s other novels: Motherland and Light. I think I should, and I may find I can, write again on O’Grady – and make something of Monaghan for it is a novel that I can’t get out of my head and am yet totally puzzled by. So watch this space.

But meanwhile this blog is about my perfect space for reading and writing. It is neither a space that is inside and outside me, infinite and finite, certainly ineffable like the spaces Ryan aspires too, as felt on the skin as a silk dress or as exposing as a empty deserted crossing between cities in the USA. It is a place where intellect is humbled by emotion I can’t quite understand or put into pattern.

A bizarre answer, but let it suffice. O’Grady is a writer who use unattributed writing from his reading, acknowledging them only at the end of his book and including Kapuściński, Berger, Camus, Fanon, Cohen, Sun Tzu, de Montaigne, Rothko, and many more. It is after a space in which reading and writing have to mix at all points – not one for attribution and precision but for feeling the width and depth of every emotion of persons irrespective of boundary. I love it.

Bye for now

With love

Steven xxxxxx

[1] Anthony Cummins & Timothy O’Grady (2025) ‘I tried to get inside an IRA sniper’s head’ in The Observer (Sunday, 6 July 2025) available at: https://observer.co.uk/culture/books/article/timothy-ogrady-i-tried-to-get-inside-an-ira-snipers-head

[2] Anthony Cummins & Timothy O’Grady (2025) ‘I tried to get inside an IRA sniper’s head’ in The Observer (Sunday, 6 July 2025) available at: https://observer.co.uk/culture/books/article/timothy-ogrady-i-tried-to-get-inside-an-ira-snipers-head

[3] Timothy O’Grady & Anthony Lott ( 2025: 7) Monaghan, Barleythorpe, Rutland, Unbound Books

[4] Ibid: 109

[5] Ibid: 79

[6] Ibid: 97

[7] Anthony Cummins & Timothy O’Grady, op.cit.

[8] Timothy o’ Grady & Anthony Lott, op.cit: 74

[9] ibid: 104

[10] Ibid: 232

[0] Anthony Cummins & Timothy O’Grady (2025) ‘I tried to get inside an IRA sniper’s head’ in The Observer (Sunday, 6 July 2025) available at: https://observer.co.uk/culture/books/article/timothy-ogrady-i-tried-to-get-inside-an-ira-snipers-head