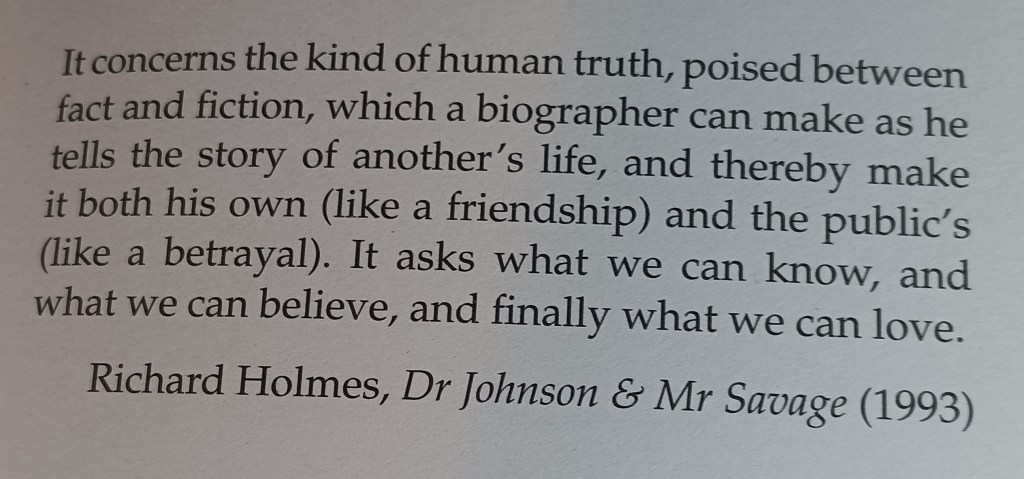

Ian McEwan states in his novel’s title a concern with What We Can Know. Clearly, this concern with the nature and limits of knowledge is central to the conduct of history including predictive history, biography and the study of the art or even counterfactual forms of those things. However, the epigram of this novel, taken from the biographer Richard Holmes, implies that biography embodies ‘human truths poised between fact and fiction’ themselves which requires the question of ‘what we can know’ but also goes on to ask ‘what we can believe, and finally what we can love’.

One way to try and understand the epigram from Richard Holmes to this novel (pictured immediately above) is that in order to know a person or people appears to require not only facts, the validity and reliability of the acquisition of which can be tested, but the ability to believe in and love the people you claim to know. In order to fulfill the demands of that whole process we need the ability to create fictions, or give credence and attachment himself to the fictive creations of others, that supplement the known facts, and are capable of integrating with them. The epigram is from a book from the same author as Footsteps, Adventures of a Romantic Biographer. The latter book is the one that the main protagonist of Part One of the novel and its first-person narrator, Tom Metcalfe informs us that he, in the imagined year 2119 of the novel’s setting where Holmes’s book is preserved as a rarity of a university library, reads (he even describes its original King Penguin cover showing ‘a painting by Hans Thoma’).

Like Holmes, he must tell the story of people long dead as well as his own, and the different historical time-space frameworks which is the context of each, as he in his time aggregates together the stories they told of themselves, each other contemporaneously and by others later in retrospect from their lives – scholars, journalists and gossips, with oft little to tell them apart. Since the ‘facts’ of which these stories tell sometimes contradict each other, he, as an academic, must test the validity and reliability of them as ‘facts’ these others narrate or his own subjective desire projects into story-form (even though they exist ‘beyond my reach of time’), his methods involve as Holmes’s do, a kind of relationship with the subjects of whose lives he tells one version of their story, as if the time between their stories were imaginatively extinguished and they live in the same time frame. Admittedly, however, says Metcalfe of himself and Holmes, as writers, the phenomenon of belief and love of the subjects of their writing was ‘a blend of hallucination and hope’.

Holmes tells (and Metcalfe repeats to us) the story of his disappointment in a hoped for hallucinatory meeting with Robert Louis Stevenson, in one of the essays in Footsteps. Holmes is retracing Stevenson’s walk to the latter’s schedule but unevenly. On one leg of the journey Holmes completed faster than Stevenson, he expectantly waits for Stevenson on a bridge that didn’t exist in Stevenson’s time of walking in the Cévennes. The meeting of course cannot happen for each of the journeys took place in vastly different time-spaces. Metcalfe thinks the subjects, the poet Francis Bundy (a fictional poet created by McEwan) for example, of his historical imagination as alive as Holmes did his, even to the extent that ‘I might have loved Vivien Bundy‘, waiting for her as Holmes did Stevenson ‘as the light fell and the bats dipped over the river‘. The layering of hopes of resurrection of a lost past become even more fantastical when Metcalfe thinks that were he to dream of meeting his heroes Stevenson and Holmes in one time-frame, though they inhabit three (one each), the meeting would in Metcalfe’s time-space frame have to be on the floor of the sea, since the Cévennes valley of Holmes’ and Stevenson’s experience was now, in 2139, under the sea between islands of high land that constitute the French archipelago since the Inundation of the low-lying lands of the globe, a happening the novel sets in a future 2042. [1]

Marlborough, Wiltshire, before the Inundation: In the novel, Marlborough has become a thriving port serving the Vale of Oxford Sea named Port Marlborough

And here we have to explain, what only becomes clear as we read on in the novel, that the world of nations of his time-frame , starting May 2119, is one where most places, though the nations themselves seem to have survived as federated island-states, we know of as the countries of modern Europe are now archipelagos, in which in the modern Cotswold Island, Marlborough has become a thriving port serving the Vale of Oxford Sea named Port Marlborough. Great lowland cities like Oxford, London, Edinburgh and Glasgow are now under water. To aid my imagination I tried to fill in the lowlands on a map of the UK in black and blue ink. My faulty version is below, but it gives a vague idea of a time-and-place-frame, for this is how we have to imagine space and time in this novel, for that phenomenon is voiced in several discourses.

My map is a rather physically messy visualisation of Metcalfe’s parameters of space and time for his Britain (the fate of Ireland being not regarded, as Kevin Power says a little sourly, but understandably so, in his review that starts with the premise of McEwan’s very bourgeois conception of a stolid ‘English’ dominated UK. Power speaks of McEwan’s ‘scrupulously national, but occasionally and endearingly purblind, liberal morality’.[2] Speaking of which, I can’t quite, for instance, explain to myself why I really should believe the South Downs would have existed as an island amongst the rest nor why it should have a university, other than it housed Charleston and out-of-London Bloomsbury once, any more than that the heir to the Bodleian library is now on the peak of Snowdonia accessible only by water-powered funicular railway. But space and time sometimes need such messy semi-ideological national realisations in science fiction. They complement other discourses of space-time in the novel, including the (fictional – for others mentioned in the book are not fictional) poet’s, Francis Blundy, notes for a poem on space and time in string theory, for his poem ‘String’:

Space and time are woven from minuscule loops into a fabric a trillion trillion times finer than silk. The loops are as small as physics allows things to be.[3]

Of course the finest material thing has to be silk – it tells of the class of people we are dealing with here, where something ‘fine’ must also be something ‘refined’ socio-culturally, just as McEwan’s earlier central characters are always as well-heeled and socially prominent as they are well-intentioned: Power mention the High Court judge in The Children Act and a neuro-surgeon in Saturday (to my mind, both are nevertheless serious politically searching novels). Power goes to redeem this novel by arguing that the ‘liberal morality’ of this novel is not McEwan’s by Tom Metcalfe’s and that we are meant to find it and its preoccupations limiting, as Tom’s students do (though they are labelled second-rate minds on the whole – the only students attracted to the humanities post Inundation being the ones who had not the mental equipment for the sciences: ‘It is Tom perhaps, and not his creator, who has the English liberal’s partiality of vision’.[2] But the limitation matters – for it is applied to the great socio-political sub-themes of the novel that matter (or should do) to 2025: climate change and its consequences, Racially interpreted migrations, and global instability and war preparations, and the awful over-stability of the class system. Perhaps McEwan subjugates these to underlying themes that characterise the space-time map of the novel’s present because in fact they don’y matter to the people of 2025, even its great literary intellectuals who maunder on about epistemology and romantic-cum-sexual attachments and call it modernism or even post-modernism.

For the overlying themes of this novel have more to do with literary authority and the relation of the content of art to its form. The latter includes the finessing of aesthetic technique (especially in poetry but not only as we see in the inclusion of the minor novelist Mary Sheldrake) and the competing voice and perfomativity of voiced and written language respectively. Strangely, the novel even has to make it clear how stable the English language has been over the period of vast changes wherein ‘race’ is no longer an issue since everyone is a kind of brown shade in skin and can trace (if they can be bothered) poly-racial origins.[4] War and ecological disasters, having done their worst in concert are no longer issues, ecological necessities being now guiders of pragmatism about what it is possible to do. The world has succumbed to Nigerian hegemony, that hegemony being entirely about cultural leadership. Even AI and social media are tamed being out of private ownership altogether. Overproduction of goods, even books, is a thing of the past. But, likewise, the upper ruling classes in The UK archipelago all live in the Pennine chain (though how they managed the boggy land isn’t made clear).

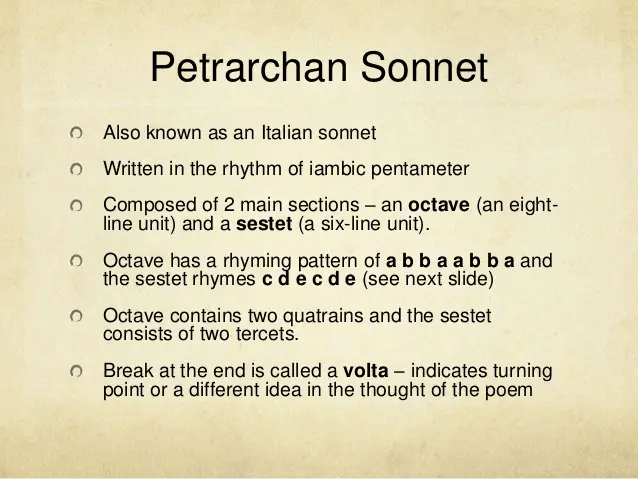

Yet the concentration on aesthetics and technique, especially around the focused poem by Francis Blundy (which we are never allowed to read – although pointed to a similar model of a ‘corona sequence’ by Peter Fuller called Marston Meadows: A corona for Prue and dedicated to his wife and a reminder of their joint mortality, not unlike Blundy though less involved with secret plots. A ‘corona’ is composed of fifteen Petrarchan sonnets, each sonnet with 14 variations of iambic pentameter lines divided into an an Octet (8 lines of course) and Sestet (6 lines) and with regular rhyme schemes. They are sequentially ordered so that he development is logical and the last line of each sonnet (in sonnet 1 – 14) is the same as the first line of the following sonnet. The 14 first lines of sonnets 1 – 14 are the same lines of the final sonnet, no 15 for obvious reasons and known as the corona (or crown) of the sequence, as must read as if a recognisable progression of narrative and voice. It sounds impressive, though clearly technique is so predominant, it takes a lot of attention away from the subject of the poem and directs it at the poet’s virtuosity. Luckily, as the the novel shows few people listen to (Percy is an exception in this book) to spoken poetry attentively or closely enough to follow more than its vague drift, given what we know of the story Blundy tells about his wife in his corona sequence.The Fuller poem McEwan mentions in his Acknowledgements is indeed a beautiful poeme, and its concern with mortality bound into notions of the co-experience of space and time. Let’s look at that poem’s ‘crown’.

Come then, we’ll walk. What else is there to do

In the uncertainties of dangerous May

And Summer coming into disarray?

We see before us underneath the blue

The ancient green world that we thought we knew.

It moves us still, whatever we may say,

And it accepts us. Though it will not stay

For long enough to be a settled view.

Onwards has always been the way to go.

Together we might make time stop or fly.

When we are parted we shall think as one

Without complaint, if matter tells us so.

And that’s just why we can’t agree to die—

So we can wander here beneath the sun.

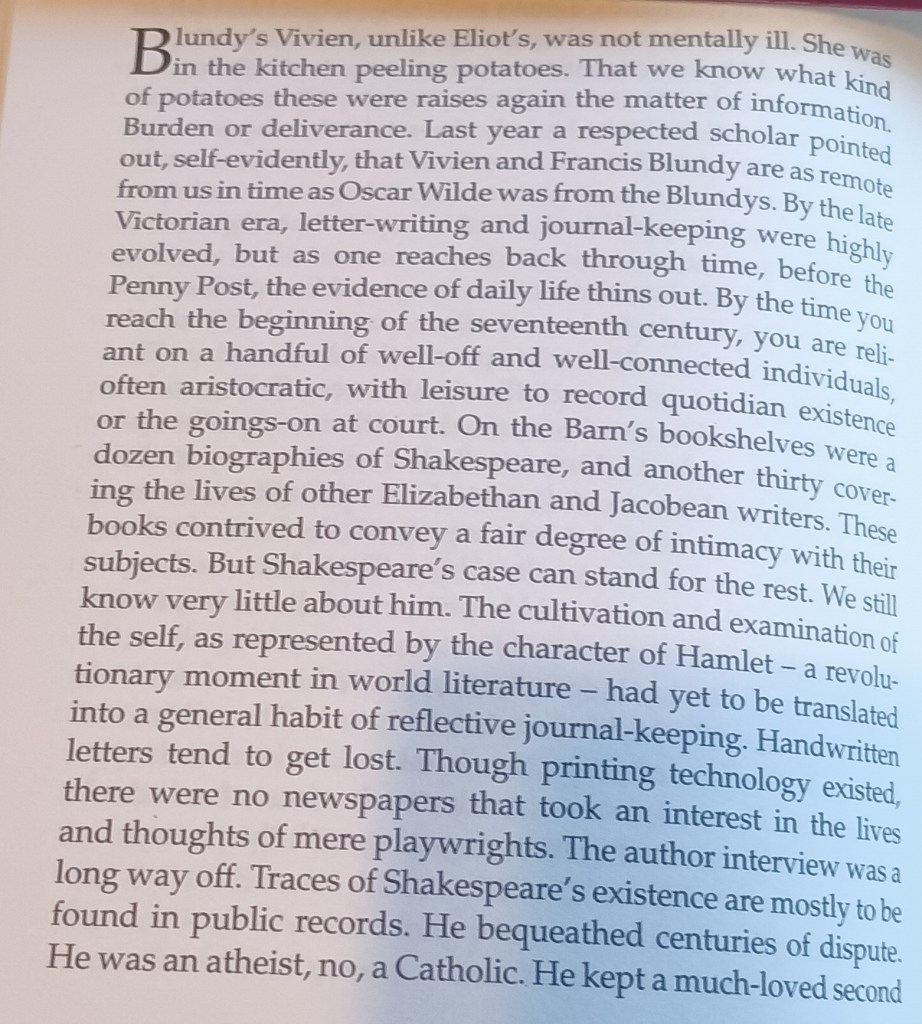

Like the 14 sonnets preceding it the sonnet is about the experience of passing time and the desire for the contradiction of its passing – that it ‘stay / For long enough to be a settled view’. The view into a spatial prospect is here aligned with the temporal prospect of the future of two lovers who must part – it is an old-fashioned trope in poetry. We desire to ‘wander here’ and not ‘agree to die’, though the logic of the passage is that time must pass from uncertainties and danger in ‘May’ to ‘disarray’ for ‘onwards’ has ‘always been the way to go’, to death and parting. It’s lovely but it is conventional. We know though we do not read it that Blundy’s poem is not. Much of Part one of the novel involves debate about whether Blundy wanted his poem to focus on ecological danger, but Part Two shows us that it may have had another purpose (no spoilers here). Whilst I do not think McEwan requires us to know Fuller’s poem, it makes sense if you do, for what Fuller feels about Prue, his wife, is very different to what Frabcis Blundy feels about Vivien, and much more complex. And it is here that space-time perspectives in the unread Blundy poem merge with the concern about space and time in the novel and the interwoven lives of its characters over great and small measured time and space gaps. You can enjoy all this for yourself, but here are tasters. Look at the time gaps opened in this early set of sentences and how they are interpreted, in relation to ‘what we can know’ (really know, that is!) about William Shakespeare despite the plethora of books about him:

My photograph of the passage is from Ian McEwan (2025: 16) ‘What We Can Know’ London, Jonathan Cape.

The burden of this passage is that Time is a space in which certainty about events and persons gets lost (later we see that this happens between islands of geographical spaces too, as I will show) and that there are trivial similarities hiding complex difference – like the comparison of the two poets’ wives called Vivien, T.S. Eliot’s and fictional Blundy’s. The time context explains sometimes that we know trivial things but not important ones – scholars in Metcalfe’s time, as in ours, point out that different times, contexts and spaces of writing promote different kinds of data as significant, partly because the reasons we write and how we write certain genres, like letters, change over time. New genres, like email, even change that focus as a matter related to the form of writing alone. Communications took longer time to pass through space even, as does. Attention to listening, reading and interpreting texts changes over time – students may be less patient of past forms than contemporary ones for instance, people listen to texts with reference to what matters in their time-space, as we see in the readings of the Corona – each audience member bound in its own preoccupations, even in short time-space differences. A man with dementia may be told very significant information, like about the death of a child of yours in the past, and seem to be insensitive because they forget it immediately.

In Metcalfe’s narrative in Part one of the novel, even a poem that only two people have read (though a few others have inadequately – in different ways- heard it, can take on the character of the time and space that accounts for it – in the views in the press that it related to a radical opposition to fossil fuel, by university lecturers as an exercise in formal and genre-related technique, as a performance by a certain social class entrained to see dinner parties as for that informal and formal purpose, or a personal dream. Time changes the purpose of things. It is akin to that period of invented history in this novel that is known by its fictional society as ‘the Derangement’, which Metcalfe says, ‘respectfully capitalised, came into general usage as shorthand for the usual list of global heating’s consequences’:

The term suggested not only madness but the vengeful fury of weather systems. There was also a hin at collective responsibility for our innate cognitive bias in favour of short-term comfort over long-term benefits. Humanity itself was deranged.

If ‘derangement’ is madness we will see it related also to the effects of dementia – ravaging the recall of cognitive spatial-temporal webs and map guides necessary to the memory of the past and projection into the future on a personal level, in Percy, or in caring for a person like Percy. There is a close and taut symbolic resonance between individual psychology, dyadic psychology and group psychology that is exemplary in this novel. At its extreme the ‘derangement’ is related to both societies and persons – or some of the latter at least – to experiences of trauma: abandonment trauma in particular whether as victim or perpetrator of that abandonment, with common enough McEwan tropes of lost, abandoned and neglected children: the canonical myth of that wondrous novel The Child in Time. Some derangements – social or personal – are dangerous. Vivien pulls her own narration up short in Part Two when she realises that her behaviours may be akin to that of a deranged violent paedophile, feeding off those abandoned children which hide in the niches of this novel, one a boy-child staring down the railway line upon which his depressed mother left him behind. It recalls her own guilt regarding abandonment of a child (to tell you might spoil – but use the note if you need to[6]). The kinds of derangement in the novel – psychological, social and political define the limits of our ability and desire (for these are related – no one wants, for instance to understand the vicious paedophile mentioned above) to know, believe and love certain individuals, and this is I think what What We Can Know does with its concerns with epistemology – testing our tolerance for all kinds of persons including Vivien and Francis.

The novel tests those tolerances for the behaviours and personalities of its characters across the gaps of time and distance – spatial and temporal. The simplest example of this is the discussion of how students in 2119 come to form judgements of persons a century before. Vivien states some of those themes in regard to looking back on joint married and co-involved lives lives when she recalls, as others have already done in Part One the ‘Second Immortal Dinner’ (the first included Wordsworth, Haydon and Keats, the second the Blundy’s and friends) when she says of her recall: ‘There exists an unregarded entanglement of memory and distance’. Entangled threads (perhaps of narrative) are deranged in the presence of gaps of space and time. It is stated better a few pages later: ‘Time and distance have obscured my memory of the order of events …, a time of arrangements and upheavals’. [7] This could be written – a time of arrangements and derangements. The passage goes on to show it is not only memorial distance that is involved but spatial ones, such as those brought about by the shifting of things and institutions in the UK as a result of the Inundation. and for Vivien a move from fashionable Headington in Oxford to the isolation of the Barn,converted to the luxury Bundy home in the Scottish Highlands. Derangement and arrangement are important binaries, and in some time-scales, must be related phenomena, for things like Highland barns have to be taken apart to rearrange in order to home rich poets.

Art is a form that involves arrangement and the potential of significant derangement of its contents and form to signify meaning, especially in a corona sequence poem, but in a novel too. Crafted forms are about the arrangement of deranged materials into those forms but sometimes bear the marks of derangements that need to slip into them too to create meaning – in written art, these are often arrangement and derangements of time and space, and this novel has much of these, but so do the cited diaries and other personal accounts in it, as well as the poems. Bundy’s corona sequence deranges entirely the time-frame of Fullers’ Marston Meadows, as it mixes past and present, even memory of the murder of a deranged man it would seem, into its attempt at ordered play with time/ Only Fuller achieves ‘ordered’ play with time.

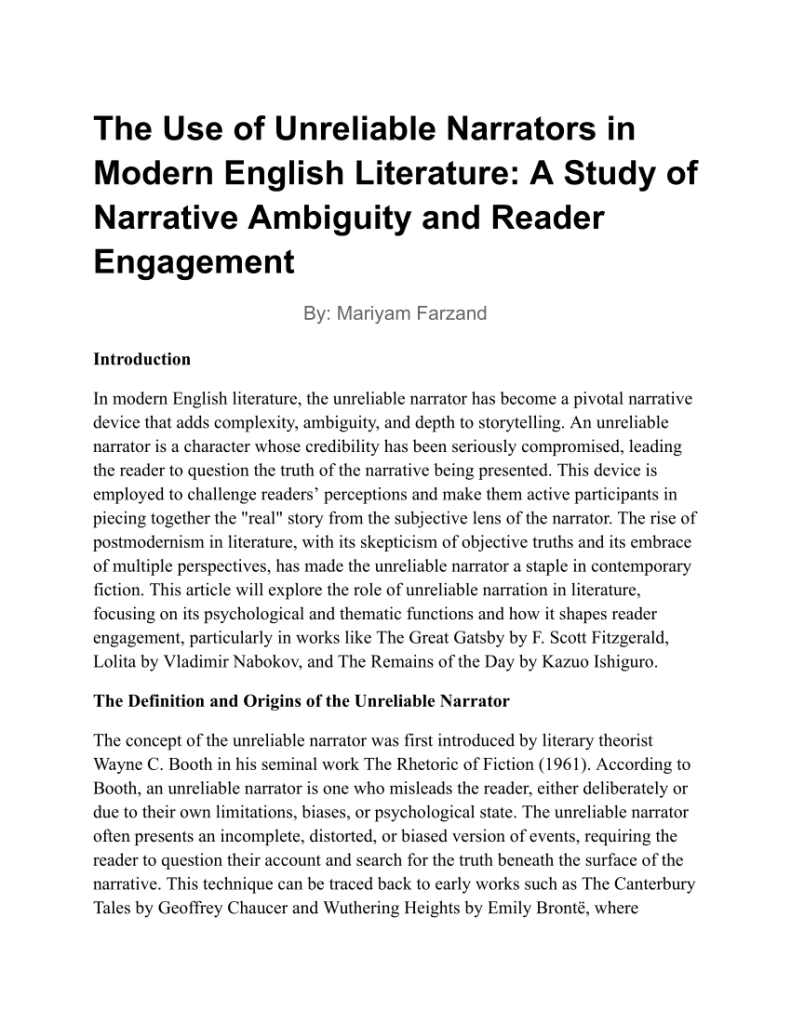

Likewise McEwan, as a master of the novelist’s craft, uses deliberately deranged materials. Metcalfe and the equally important narrator in Part Two, who arranges and deranges the Part One stories very differently, in this novel are examples of the classic element in novelistic storytelling, the unreliable narrator, as described by Farzand below:

Kevin Power is probably correct to see Tom as a unreliable in a different way and calls him a ‘deeply elusive narrator’, with a ‘partiality’ with regard to his material partly based on the blinkers of his liberal ideologies and partly via his existential (Heideggerian) thrown-ness in a different time and space than the characters he wants to bring back in our consciousness as readers to something that reads as if it feels like life. He is, of course, an unreliable narrator of stories that are written down (in various media) by equally unreliable narrators. He even misses the story that becomes Part Two which is unearthed in the process of the novel – something similar happens in A.S. Byatt’s Possession. Part Two, as I have hinted, is the narration of stories told already in Part One but from a totally different perspective, on the truths of them, but is equally unreliable as the story the same character tells in Part One as Metcalfe reads it and other accounts of the same events.

We can’t get over the fact that novelist worth their salt must be an expert at arrangement in sometimes deliberately deranged (or if you prefer unreliably ordered) ways in good writing. Some critics see problems in this. Nick Duerden in the i newspaper , for instance, writes

There are times during What We Can Know when it feels as if the author is trying to stitch two distinct books into one, offering two perspectives on one story when each might have been strong enough to stand alone.[8]

But surely those times of mismatch between two stories and their contextual background histories are the point of the novel, which, anyway, certainly has more than two perspectives on the same story. The ploy is an old one – it is the remit of Browning’s The Ring and the Book, for instance. Any arrangement is by nature probably the de-arrangement (derangement) of someone else’s story of apparently the same thing and the novel makes it plain this is true of personal autobiography (where the two perspectives sometimes inhabit one body where one is unlikely to tell whole truths or cannot), detective and murder fiction, romantic love career stories, elegiac fiction (Vivien is liberated, for instance, to discover that it is possible to turn grief into a liberation as she finds a woman who celebrates her sick husband’s death. [9] Or, let’s face it, the same is true of the telling of ‘history’ – even before it becomes counterfactual or projects into science fiction, it becomes a reflection of interests involving the teller of the tale – as the various memories of the event called the ‘Second Memorial Dinner’ in this novel show.

Art in McEwan share the same modernist and post-modernist dilemma (personally I think that dilemma considerably postdates those movements) that art is no longer an element reinforcing the control and stability possible in a world where ‘what we can know’ is unlimited, or at least has nostalgia for that supposed strength in art that surpasses the ‘partiality’ of other kinds of knowledge systems. There is a wonderful moment when Bundy quotes, without naming the poem, Tennyson’s Ulysses, the lines being: ‘We are not now that strength which in old days / Moved earth and heaven.’ In fact he misquotes by placing a full stop at the end of those lines missing out Tennyson’s hero’s acceptance of his belated partiality: ‘that which we, we are’, which follows the comma after ‘earth and heaven’ Vivien hearing this says these are: ‘Famous lines from my favourite Tennyson poem, and generously spoken’.[10]She thinks they are ‘generous’ perhaps because both are read of oration of a poet about his purpose who isn’t has decayed as he pretends to be, that is – still a power to move ‘heaven and earth’. We will see later why this matters to Vivien who needs her ‘heaven and earth’ moving a bit.

But Blundy thinks he can, like Fuller, shift the relations of heaven and earth in his ‘Corona’ as Fuller did for his wife, Prue. Arrangements and derangements are the job of poets – though not usually, at least in public, in the practical living of one’s disordered love life – although surely the novel helps us see T.S. Eliot and his relationship to his deranged wife, Vivien, in that light, as a reading of The Waste Land. There is another idea on the margins or raised beaches (see my blog on that phenomenon) of this book – the idea that the world deserved both the historical Derangement and Inundation it received because there were too many books in it in the early twenty-first century (it is a thought Vivien has in a bookshop as she prepares to add one more on John Clare). [11] For me that moment rhymes with one in the world of Tom Metcalfe who has considerable difficulties accessing books, and says than in his world ‘many books have been lost’. The theme again is an old one – it recalls the ‘drowning of the books’ dream of Wordsworth in Book 5 of The Prelude, where inundation promises to drown all the wisdom of the world – and thrust forever the authority of books from the world. And so why write at all? Except that writing promises a way of understanding the contradictions in our desires for order and disorder, authority and anarchy, the arranged worls and a deranged one – for most people require both impulses in order for them to ‘get on’, as do all the characters in this novel.

That is a deeper pit than I want to dig – and the novel has enough pits in which the truth of books may be buried in it already. Read the book. It is a masterwork – if only because it either states or cleverly conceals these contradictions in its pleasures.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxx

________________________________

[1] Ian McEwan (2025: 78-80) What We Can Know London, Jonathan Cape.

[2] Kevin Power 2025: 51} ‘After the deluge’ in The Guardian Saturday Supplement, Sat., 20/09/25: 51.

[3] Ian McEwan op.cit: 9

[4] See ibid: 98 & 162 respectively

[5] ibid: 191: ‘…he too was the slave of a sexual compulsion’.

[6] Diana’s story ibid: 204 – 6, 258.

[7] ibid: 272 & 276 respectively.

[8] Nick Duerden (2025: 47) ‘Even now, at 77, Ian McEwan still loves to wrong-foot us’ in the i newspaper (Friday 19th Sept. 2025), 46-47.

[9] For the latter, see Ian McEwan op.cit: 257f.

[10] ibid: 223

[11] see ibid: 201