Thrown to the pit of Hell, Satan in Paradise Lost looks around him:

At once as far as Angels kenn he views

The dismal Situation waste and wilde,

A Dungeon horrible, on all sides round

As one great Furnace flam'd, yet from those flames

No light, but rather darkness visible

Serv'd onely to discover sights of woe,

Regions of sorrow, doleful shades, where peace

And rest can never dwell, hope never comes

That comes to all; ....

This is in the epic poem of a man who was, by the time of writing it, blind; so the idea of ‘darkness visible’ was a personal one to him. It denotes a space in which it is always, to the eyes at least night, were it not for other senses awake to the day’s sounds and smells and sensations on the skin that differ, when they do, from those at night. Before Milton shows Satan seeing, but seeing through the medium of darkness, the poet had prayed that some power – his muse or God – would:

...: What in me is dark

Illumin, what is low raise and support;

That to the highth of this great Argument

I may assert Eternal Providence,

And justifie the wayes of God to men.[1]

Strangely the work that has responded most and in a similar way to the difficulty of justifying the ways of God (or if not God, the laws that sustain ideals in the world) to ‘men’, who are resistant to believe in them and ‘illumin’ what is dark – those hidden and secret under cover of darkness or some other kind of shadowy socially validated obscurity, is To Kill Mocking Bird. In it people are faulty but the ideal of the law has to be upheld – up to a point, as I will show. Of course the issue for the modern novel is the need to justify the persistence of racism despite law and the principles of equality behind it and, perhaps, to justify other kinds of ‘othering’ – like class and the spiky one, for the period, of the integration of the mentally ill into the community. It depicts a society in which large parts of the society were active in, or collusive with, racist violence, and the best – very few – had mainly a passive attitude to the continued racism of entitled White communities, if one that refused to collude, at least in the ways they thought, spoke, and fulfilled their social roles. In a novel where the hero denies the existence of the Ku Klux Clan in the 1930s, he shows that a white lynch-gang doesn’t need the symbolism of such racist terror. [0]

Segregated communities like that of Monroeville, Alabama in the 1930s, the town inhabited by the Lee family in Harper Lee’s childhood set in 1932 (and confined to that year in the film), were spaces in which the hegemonic values of only a part of the community, white and financially able to survive, even if only just, economic trials prevailed. Hence, when white residents of Monroeville who remembered it in the thirties (some of them being the actual models of the characters living in Lee’s fictional version of the town in 1932 onwards,Maycomb), are asked (as they are in a documentary called Fearful Symmetry: The Making of ,To Kill A Mockingbird’ by director Charles Kiselyak) about the town, they still romanticise and defend the values of the white community as inclusive and ethical. Some insist that the segregated Black community shared exactly those values in the main.

Happy to recall that there were violent racists at work in their society, these older people’s view at the time of the documentary film’s making in 1998 remains that most white Southern people were not actively racist and were capable of speaking up against racism in social or work situations. But clearly the degree to which they spoke up varied, with the vast majority maintaining silence rather than challenging racism themselves, often delegating that task to those like Harper Lee’s father, and the Atticus Finch based on him, who saw themselves as modelling the best values of the community, so others need not do so.

Even the type of the White intellectual in local administration of affairs and laws, represented by Atticus Finch, stopped short of any identification with other less visible communities to engage in active political resistance or credence to Black resistance counter to the mechanisms of racism at the social level. And truth to tell, the silence and invisibility of ‘othernes’s’, whether in the existence of segregated facilities and spaces for black people or of the intermediary spaces filled by poor whites, and within them, those known as ‘White Trash’, kept also any demand to act for the othered to make them more visible and heard also as unseen, unheard and unfelt as the othered persons themselves were.

Amongst those othered were those with mental health issues or who had enduring difficulties in learning. Hence, I think, the central place in this novel as the key representation of otherness in this novel of Arthur, known as Boo, Radley. Much of the learning of the novel is not posed by Tom Robinson, the Black man falsely accused of rape, who remains a passive and fearful victim of lies throughout but the man said to represent the mockingbird cited by the novel that must not be killed, Boo. That is so because the political stance of the novel is set by attitudes that are presented as universal but applied only to individuals never to categories of person, such as Black people as a group. It is the ethical principle that all individuals must be respected for who they are and with knowledge of how they came to be, thus, including through their socialisation. Of course, having gone feral, like the rabid dog in the film, they can be legitimately shot, as the frightened Tom Robinson is, if out of sight unlike the feral dog.

As she recalls in later years, father Atticus Finch explained to his tomboy 6 year old daughter Ann Louise Finch (or Scout as she preferred then to be known) the basis of his ethical principles thus:

“First of all,” he said, ” if you learn a simple trick, Scout, you’ll get along better with all kinds of folks. You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view – “

“Sir?”

“- until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” [2]

It is worth considering the political stance carefully because of its claim to universality,- it applies to ‘all kinds of folks’ (although Atticus never abandons the supposedly sex/gender-blind pronoun ‘he’ and thinks he includes women in it) such as the racist and bullying Mrs Dubose, with her Confederacy rifle secreted on her person – according to Jem – and, to the children, the ‘meanest man in town’, Mr Radley. The pertinence of the ‘trick’ is that what remains unseen to us in life is that hidden under the skin – black or white or any of multiple hues – the roots of an individual’s shaping influences.

And this matters in a community where exclusion stalks the fields during every daylight hour and hides people, even whole groups of them, from each other, even from the community which sees its superiority in its visible tangible hegemony, the white community, which the film recreated in a set in Hollywood – clearly make-believe reality. White Maycomb barely know of the lived lives of some others and how they developed thus, especially invisible to them is the sequestered and segregated Black community whose children even we ‘seldom see’, as Lee wrote to Oprah Magazine ‘until, older, they came to work for us’. [3] This is the reason why Calpurnia has such an important role in the novel – one rather depleted in the film because we never see Calpurnia taking the children to her own church and then to her home.

Calpurnia, the Finch’s servant, has the role of a mother to the Finch children, but whether we truly are allowed to walk in her skin by the film is doubtful. L to R: Phillip Alford, Estelle Evans & Mary Badham.

The 1962 film makes a kind of symbol of this by having a Black boy about the same age as Jem, when Atticus visits the home of his Black client, Tom Robinson, exchange a hand salute of greeting through the Finch’s parked car’s closed window. It is closer, we can see, than Jem ever gets otherwise to a Black peer but not that close. The distance remains because Jem is forbidden to enter the Robinson shack with Atticus. That unexplained detail tells (in my mind anyway).

Yet this novel does not even contemplate creating a bond between the children in the novel and a peer (someone of the same age) who is Black. It is a novel that begins and ends with the problem of the invisible other negotiated through the role of the preternaturally White Arthur Radley, Boo, who lives in the same street though, it is believed by the children, possibly confined in a cellar and allowed out only at night when he is less likely to be seen or be coloured by the sun. In the film Robert Duvall playing Boo was given only one line and that was removed at editing, and when finally visible is of a whiteness so complete it is ghostly (explained of course as an effect of being a long time removed from the effect of the sun), as we see in the film still below:

Boo Radley and Scout. L to R: Robert Duvall & Mary Badham

That is why I give the quotation I do in my title, though it is rather differently worded in the novel.

Jem said, “He goes out, all right, when it’s pitch dark. …I’ve seen his tracks in our back yard many a mornin’, and one night I heard him scratching on the back screen, but he was gone by the time Atticus got there.

“Wonder what he looks like?” said Dill.

Jem gave a reasonable description of Boo: Boo was about six-and-a-half feet tall, judging from his tracks; he’ dined on raw squirrels and any cats he could catch, that’s why his hands were so blood-stained – if you ate an animal raw, you could never wash the blood off. There was a long jagged scar that ran across his face; what teeth he had were yellow and rotten; his eyes popped, and he drooled all the time. [4]

The vision of horror produced by a child of Jem’s limited imagination owes more to animal nature and a negative vision of aging bodies than it does to super-nature, but clearly Scout’s adult narration of her early visions has a much more writerly imagination behind it, not least one that she might share with Dill Harris, for Lee never really contradicted the belief that young Dill was modelled from memories of Truman Capote as a friend. Later, it was Capote’s imagination that re-envisioned viscerally the grotesque murder of a whole family in In Cold Blood, a novel Lee honoured. Truman, Lee said in an essay on him, said he ‘never really had a childhood’ and by keeping ‘his own counsel’ was able ‘in his apartness’ to ‘quietly pursue his craft’ as a writer (he wrote his first novel she says, though now lost, aged 10 (about three years older than Dill on his first ‘puny’ appearance)). [5]

Scout, Jem and Dill. L to R: Mary Badham, Phillip Alford, & John Megna

In the novel Charles Baker Harris, known as Dill introduces the other children to the film of Dracula and in the telling thereof reduces ‘Dracula to dust’, though while living Dill can tell the ‘old tale’ such that ‘his blue eyes would lighten’. Here was a thing – an object of terrified imagination – that only came out at night that impressed Jem, who thought the film was better than the book, but whose fiction-weaver Dill becomes for the other children ‘a pocket Merlin, whose head teemed with eccentric plans, strange longings, and quaint fancies’. Hence, when Scout as an adult supposedly describes the Radley Place, it does sound othered in the manner of Dill’s ‘strange longings’, though she feeds off the imagination of both boys, filled with a kind of decaying Gothic grandeur, although in prose cleverly undercut by Alabama reality, almost to show Scout less prone to complete fantasy than the boys. Isn’t it her, via Dill, who sums up the house and inhabitant thus: ‘Inside the house lived a malevolent phantom’, going out ‘at night when the moon was high’ and capable of breathing death into garden azaleas, and mutilating chickens and household pets, scaring even ‘the Negros’. The prose allows us to laugh at the recognised childlike minds in a grown up way. [6]

Aging alone robs the legend of Boo from the power it has in young minds but the adult Scout only tells us this as as the younger self she writes of ages:

The Radley place had ceased to terrify me, but it was no less gloomy, no less chilly under its great oaks, and no less uninviting. … / … //

It was only a fantasy. we would never see him. He probably go out when the moon was down and gaze upon Miss Stephanie Crawford. … He would never gaze at us. [7]

A Gothic fantasy of Dill’s sort turns into a kind of spiritual romance-cum-sexual fantasy, where Boo is the ideal guardian angel of the Finch children as they develop, one which Scout is not yet aware will be near the truth, though we will learn that Boo is not merely a man who gazes at unmarried women with heavens knows what motivation. Boo, that is, is a fantasy originally charged with fear who transforms its ‘otherness’ into a kind of instrument of redemption, prefigured by the gifts he leaves Jem and Scout in the knot-hole in the old oak outside his father’s house, until that is Mr John Radley cements it up.

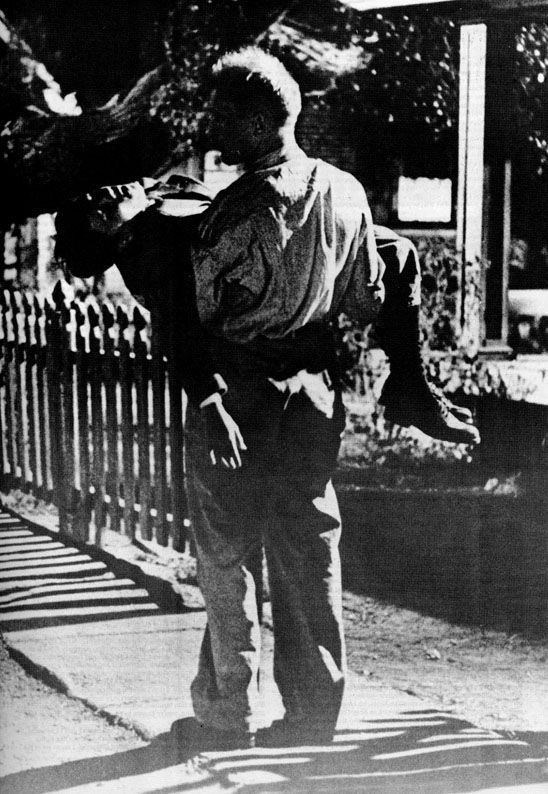

And yet Boo is still the other. When he carries the apparently lifeless body of Jem back to Atticus, the film deliberately references the still of Boris Karloff as Frankenstein’s monster carrying a dead girl child from that iconic movie. Fantasy has many ambivalent gentle giant monsters who mean well.

But the whole point of this framing narrative of Boo Radley is precisely geared to the redemption of otherness from darkness visible and shadows (in the film the only contact the children have with Boo is with a spectral shadow, an absent body made visible by darkness, that reaches out to touch Jem’s head.

The latter is a gesture repeated by Boo in the flesh when Scout gives him the permission to ‘pet’ Jem, since he was unconscious and couldn’t forbid such touching as he would if awake. The whole of the story of the redemption of Boo from negative otherness takes place at night or in the dark. When Jem is attacked at night from behind but saved by Boo, no-one sees this happen, for Jean Louise is shut in her Harvest Festival ‘Ham’ costume (a ‘Halloween’ costume in the film because of it duration over only one year unlike the book) and her vision occluded, even if it weren’t too dark to see. Boo becomes a guardian Angel, but still works in the dark until his face is ‘illumin’d’ to Scout after his quick action to rescue Jem and bring his unconscious body home to Atticus. It seems the grace of life in Maycomb is restored by this act of near magic in the obscurity of unlit nature.

Yet the novel leaves us with the puzzle. We know Boo stabbed the ‘white trash’ figure that is Ewell, incestuous paedophile, drunk and liar (a stereotype of ‘White Trash’), and we know that Boo first came to notice as a potential danger when he stabbed, with another knife, his father in the leg as a child. Canny readers know that the Sheriff and Atticus are right to pretend this did not happen at the end of the film showing that the law itself must be blind in another way than the allegorical figure of intends – that Bob Ewell slipped and fell on his own knife. However, if cannier still, they will see a deeper link here to the moral structure of the novel. In both cases, Boo stabs a paternal abuser, mean men who use their goodness in their children to evil ends. This is even more problematic in that it ought to have been Tom Robinson, that muscular but maimed Black man, who (with the aid of Atticus Finch) ought to have revenged the child-abuser, Ewell.

Atticus Finch and Bob Ewell in the court room at the point at which Ewell thinks Finch will collude with his crimes and ensure the racist false prosecution of Tom Robinson, Ewell’s scapegoat for his own physical and sexual abuse of his daughter. In the film Ewell scrubs up rather too well for the pure white trash he appears as in the novel: L to R: Gregory Peck & James Anderson.

in my view, this reveals why this novel is as much a problem novel as Shakespeare’s plays can be ‘problem plays’, and fail to resolve problems as ethics would suggest they ought to be solved. And this, I think, is because the novel, in preserving a nostalgic look at the white communities of Alabama and their capacity for redemption in memory, does the dirty on its black characters (and the film even more so). This is especially of Tom Robinson, who Atticus even blames for his own death – because he had a good chance at appeal, had he not distrusted the bias to whiteness of the legal process, a thing he has more reason than Atticus to believe to be the case.

Atticus Finch and Tom Robinson. L to R: Gregory Peck & Brock Peters.

There is a curious moment in the 1998 documentary referred to above when Brock Peters being interviewed speaks of how shaped were the emotions he demonstrated as Tom by the director. My own reading of that is suspicious of the fact that even in representations, Black actors were asked to stay within stereotype – Robinson is presented as a simple man, ‘stupidly good’ in Milton’s term – though Milton is peaking of the Devil, who cries rather than gets angry and resistant to the oppression that even a white girl he pities for his father’s use of her oppresses him vilely to save herself from her father. Yet there is a reason for that refusal of anger and violence.

Until my father explained it to me I did not know the subtlety of Tom’s predicament: he would not have dared strike a white woman under any circumstances and expect to live long, so he took the first opportunity to run – a sure sign of guilt.[8]

Tom is trapped. Tom cannot explain away his apparent ‘sign of guilt’ without exposing the contradictions in the white morality in relation to both black people and white women, and this, as certainly as the terrible sin of a Black man pitying a white woman would have condemned Tom anyway. When Atticus sums up before the court, he attempts to explain this predicament and accuse white society of thinking of Black men in terms of stereotypes or an ‘evil assumption’ of Black perfidy, but to defend Tom, Atticus can only describe another Black stereotype – the one given by Lee’s writing as a ‘quiet, respectable, humble Negro’ [9] – but it hardly gives Tom the complexity of Boo Radley, another ‘victim’ of stereotypes, who remains as mysterious as he was when the book ends.

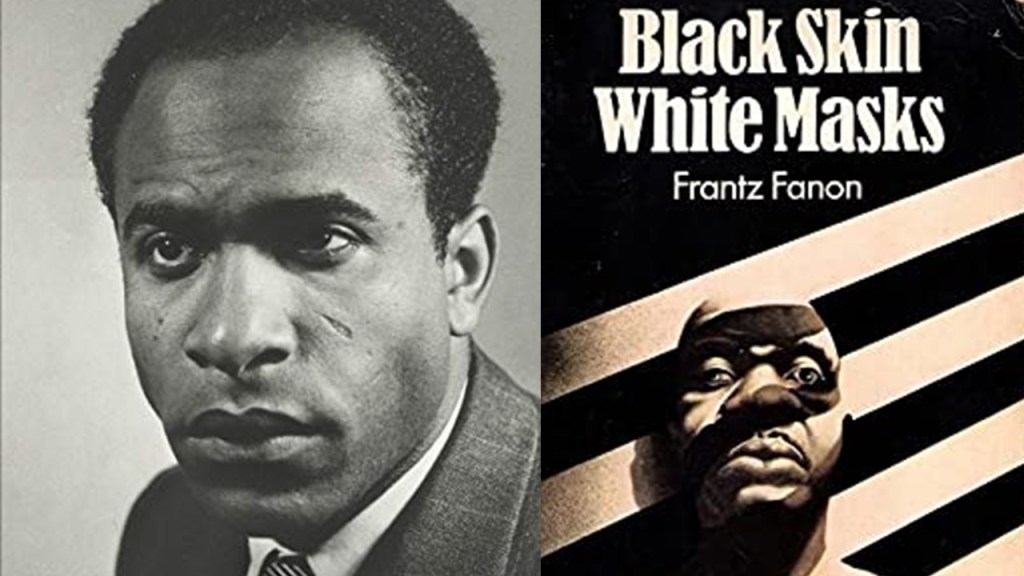

The cost of saving White complicity in racism is that Black people must be seen as unknown because segregated, but with the assurance that, if they were not segregated, we would know them as one like us, if never one of us – a phenomenon in Tom Robinson that Franz Fanon would describe as Black Skin White Masks.

Harper Lee may have have very complex concerns about how to represent Black culture and Black people without failures of both knowledge and empathy, either s a result of the segregated society that birthed and socialised her, and because she was concerned to redeem that society in as far as possible and to discourage Black militancy. By the 1950s, when this novel was being written, Alabama was the centre of resistance to racism that was not the product of well-intentioned believers in the good intentions of White democratic law, but by Black group organised resistance that knew the law and its implementation were stacked against their civil rights. Atticus never rises to speaking for civil rights as such.

That Lee may have known this bears on the major difference between the Horton Foote filmscript and her original novel. Foote collapsed the events of the novel into a year’s duration, already softening the sense of the sheer persistence of white discriminatory practice. Lee’s novel, with its constant symbol of the watch, emphasises observed time over long durations, something emphasised by a beautiful passage about the nature of seasons in Alabama. [10] This passage gives way to an instance of one winter in Maycomb that this passage led us to believe happens rarely. Snow even falls.: the children think that the ‘world‘s endin”, but soon lean that they now may try to fulfil White European childish dreams of making a snowman. Of course there is not enough snow, so the build a man of earth, presumably black earth because Scout says:”Jem, I ain’t ever heard of nigger snowman”. The problem is eventually resolved by using the little snow that fell and ‘plastering it on’ the earth figure (who looks too much like a fat neighbour of the children). Atticus calls the figure a caricature and demands it be changed, but when its sex/gender is modified by dding Miss Maudie’s summer hat to it, Jem thinks he has saved himself from such accusation.

Lee, in the character of the learned Atticus, calls this mix of male/female/black/white characteristics a ‘morphodite. [11] Morphodites are explained in the website linked to the word in this sentence.

This fascinating word holds a unique place within the realms of biology and linguistics. Morphodite typically refers to an organism or entity that exhibits characteristics of multiple forms, often within a single individual. This concept is not merely a linguistic curiosity; it touches on various scientific disciplines and carries implications in ecology, genetics, and even cultural discussions.

The etymology of «morphodite» can be traced back to Greek roots, with «morpho-» meaning shape or form and «-dite» referring to a type or entity. This word has been adapted in various contexts but retains its core meaning related to diversity in form. By understanding the origins, we can appreciate how this versatile concept has evolved in modern usage.

Clearly this morphodite may not cross defined species categories but it does cross nearly every human category that is socially constructed whilst passing itself of as the product of ‘nature’ alone: race, sex/gender, status in community, class and so on. Is not it anyway a black skin with a ‘white mask’ (one that melts quicker than its underlying earthen structure will wear. Did Lee plan to have this episode precisely to show racial typing in figure-making, a stock in trade of the novelist. In the novel Aunt Alexandra is meant to be a believer in biological determination under the name ‘heredity’. [12] But Lee does not undermine this view entirely, though she clearly shows it is not biologically determined, any more than femininity or masculinity for Scout, who resists feminine socialisation as long as possible. The true determination of classifications of people – she uses the most persistently unchangeable version of such, the ‘caste system’ to undermine, is really about familial-social not familial-genetic transmission down generations she argues (‘attitudes, character shading, even gestures, as having been repeated down the generations’). [13]

And we have to acknowledge Lee admired this communal identity-making. As a result I think the novel struggles to really de-other the other: the Black community’s transition to political awareness and self-defence is suppressed, as is queer sexuality (the ‘strange longings’ of Dill), and neurodiversity. Boo is redeemed, for instance from being the source of nasty crimes against animals against but only because the true culprit is found – ‘Mad Addie’. Stereotypes of mental health, race, sex/gender survive the fact that a novelisrt an imagine ‘morphoditism’. I never read this novel until now but I am truly glad of this. it is powerful writing but in the classroom it is problematic. Are the various categorisations of Black people really possible to teach: Black children are usually resilient to the collusive racism of the novel’s unintentional whitewashing because they have experienced racism so often, even early in life, but it might be difficult to sit in a class who think this novel is a fine statement of anti-racism, whereas it silences true Black voices – or those of other othered groups – even poor Whites. For instance the novel uses the Cunningham family o show redeemable decency in poor whites by exposing Aunt Alexandra’s inability to distinguish them from true ‘White Trash’, Bob Ewell and his family. There is no resistance to the continued existence of categories that are and always will be oppressive – for otherwise it would be hard to look back with warmth at Maycomb or the real Monroeville. Yet this is fine writing. It ought to be used to teach the limits of White liberalism, but I bet it ain’t.

However I am longing to see the new production on 22nd January. How will it deal with problems of the proxemics of the ‘other’ in novel and film, for instance? These questions are on the top of my mind:

- Will the segregation of black people be as represented as well, if silently and without overt notice, in film and novel? Certain clues make me feel this will be handled differently. Will it be handled radically?

- Will the use of adult actors to play the child roles change things, and denaturalise the binary category children / adults, and show it as constructed?

- How will the terrible issues of the representation of an abuse poor white child be handled? Will Mayella Violet’s view that Finch too can be an oppressor be validated?

Will the segregation of black people be as represented as well, if silently and without overt notice, in film and novel? Certain clues (see above) make me feel this will be handled differently. Will it be handled radically? How will

Will the use of adult actors to play the child roles change things, and denaturalise the binary category children / adults, and show it as constructed? L to R: Atticus (Gregory Peck), Scout (Mary Badham); Atticus (Richard Coyle), Scout (Anna Munden).

How will the terrible issues of the representation of an abuse poor white child be handled? Will Mayella Violet’s view that Finch too can be an oppressor be validated?

But enough for now. Back to talk about Bryan Washington after reading Palaver. And, of course, back, if I have anything to say, after the visit.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxx

______________________________________________

[0] See p. 162 for reference to KKK. The lynch gang is pages 166-170. In Harper Lee (2020 60th Anniversary ed.: first published 1960) To Kill A Mocking Bird London, Heinemann.

[1] John Milton Paradise Lost Book 1 (1674 version), available: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45718/paradise-lost-book-1-1674-version

[2] Harper Lee (2020 60th Anniversary ed.: 33, first published 1960) To Kill A Mocking Bird London, Heinemann.

[3] Harper Lee (2025: 187) ‘A Letter from Harper Lee originally in O, The Oprah Magazine, July 2006′ in Harper Lee The Land of Sweet Forever London, Hutchinson, Heinemann / Penguin, 185 – 187.

[4] Harper Lee, 2020 op.cit: 14

[5] Harper Lee (2025: 164) ‘Truman Capote’ originally in Book of the Month Club Newsletter, Jan. 1966′ in Harper Lee The Land of Sweet Forever London, Hutchinson, Heinemann / Penguin, 163 – 167.

[6] Harper Lee, 2020 op.cit: 8f.

[7] ibid: 267

[8] ibid: 215

[9] ibid: 225

[10] ibid: 66

[11] ibid: 72 – 75

[12] ibid: 143

[13] ibid: 145

3 thoughts on ““Boo only comes out at night”, so says Jem Finch in the 1962 film of ‘To Kill A Mocking Bird’. What does it take to make ‘darkness visible’. This is a blog preparing me to see the touring production of the play by Aaron Sorkin at the Lowry Theatre on 22nd January 2026.”