Reading ‘right now’ or reading forever!

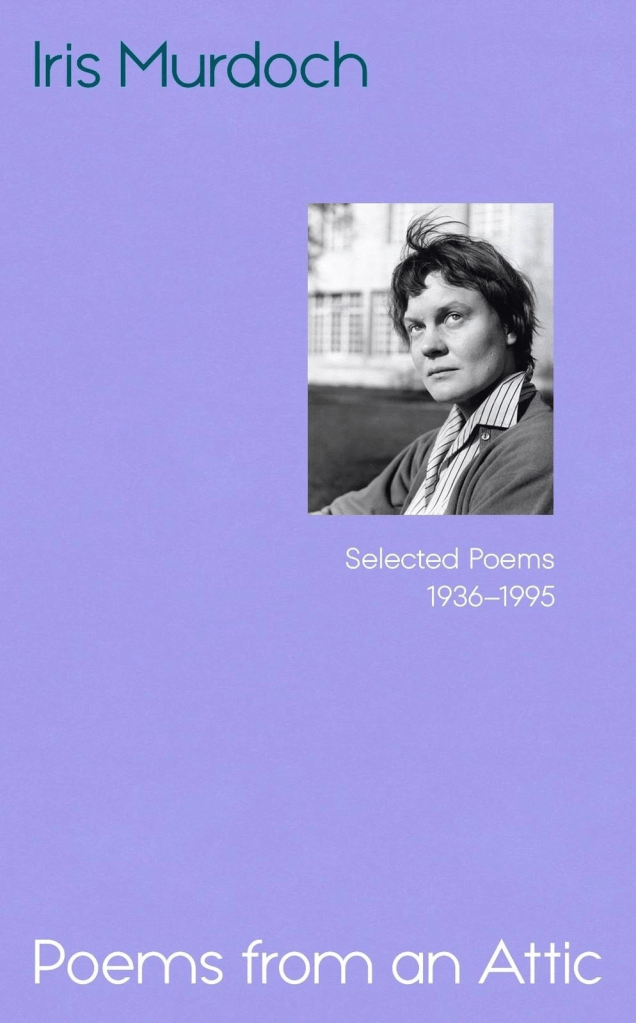

In truth I am reading a newly published book of poems by Iris Murdoch, and I think I would like to blog more seriously on them later. They are published as the result of a dusty box of manuscripts being found after searching the attic of the late home of Iris Murdoch, after the death of John Bailey’s second wife – the first being Iris herself – Audi Bailey. However, I wanted to record first my reaction to only one of the poems, The Agamemnon Class 1939. That poem, unlike many others from the box, has been aired more than once before – published in the Boston University Journal (volume 25, issue 2) in 1977, and then published in Poems by Iris Murdoch, a 1997 collection though a limited edition of 500 from the University Education Press in Okayama, Japan, and edited by Yozo Muroya and Paul Hullah.

My copy

But I ‘unearth’ the poem from the book I am reading ‘right now’ because it is a poem about about reading a book, which shows that one reading can last a lifetime, itself being read in memory through the development of events and changes of mind. The book being read in the event of the poem is Aeschylus’ Agamemnon. We are reading through resurrected memories of an experience, in one specifically situated earlier time and space, that was a group reading from a taught class on how to read that text led by Professor Eduard Fraenkel.

Fraenkel’s 3-volume edition of Agamemnon has a very scholarly commentary. That commentary is contained in the huge density of Volumes 2 and 3; both twice the mass of Volume, that itself contains:

- the prefatory material – Prolegomena for the classically inclined academic, as most readers of this text would be;

- Aeschylus’ text in Greek as edited by Fraenkel, and;

- Fraenkel’s English translation of the text.

Fraenkel was an immigrant, forced out of Germany by Hitler’s laws forbidding the employment of Jewish scholars in German universities. As Wikipedia says, in its entry on the scholar, he:

developed his thoughts on the play in his weekly seminars held from 1936 to 1942. From March 1942, a group of friends around the Latinist R. A. B. Mynors and the historian John Beazley began to support Fraenkel in the process of preparing his notes for publication. Parts of his work, including a translation of the Greek text, had to be translated from German into English. In 1943, Fraenkel submitted a manuscript for a commentary on the play to Oxford University Press. Although Kenneth Sisam, the responsible delegate of the press, took a favourable view of it, the publication process was held up due to concerns about the manuscript’s exceptional length, leading Sisam to describe the commentary as “a Teutonic monster”.

This master work on Agamemnon is testimony to the line-by-line reading that owed much to the contributions of students selected to be in that class and is described by Iris Murdoch’ friend and official biographer, Peter Conradi, in Iris Murdoch: A Life. We already know from that work, which itself reads the poem that is my subject here, that Fraenkel was more than a tutor to Iris Murdoch, who accepted a place in his seminar and private tutorials thereafter, knowing his reputation for intimate touching of his female students (Iris was watned about this by fellow student Mary Warnock, who overdressed in order to take part in Fraenkel’s teaching events to protect her body from his touchy-feely intrusions.

Conradi made it clear that the class was fearsome. Fraenkel made clear his contempt for the shallowness of British education in the classics and had a reputation for both sensitivity to what poetry is and philological and grammatical accuracy of reading, standards he launched against the papers presented by students, mainly in pairs, on specific lines from Agamemnon they had prepared together before the class. It is this dreadful of academic exposure that Conradi believes is uppermost in the poem I am dealing with here, when he cites in his biography. It was Fraenkel’s contribution to that class he supposes to give it an ‘unforgiving air’, an intolerance to grammatical, philologicsl and readerly error.

Do you remember Professor

Eduard Fraenkel's endless

Class on the Agamemnon?

Between line eighty-three and line a thousand

It seemed as if our innocence

Was lost, our youth laid waste,

In the pellucid unforgiving air,

The aftermath experienced before,

Focused by dread into a lurid flicker,

A most uncanny composite of sun and rain.

For Conradi, Murdoch like other partipants in the class felt fear, at 19 that might easily be called ‘dread’, in that class because Fraenkel was so given to shaming his students for errors of reading in their papers, and indeed for those of published classical scholars he despised. He refers us to the expression of that dread of public shaming in the poem; the dread of being shamed, in the eyes of our peers, if we were unable to answer a question angled at us by our teacher that we knew we ought to be able to answer. The example she uses of such a readerly errors in a student is, I think, no mere random example as Conradi believes it to be. She summons a situation of dread in rhat class where it appeared;

In public that we could not name

The aorist of some familiar verb.

I will return to the specific error mentioned here in my reading of the poem. Conradi treats its specificity as that of a mere rather typical example of a student making a grammatical mistake. What matters in the poem he says is:

its deliberate conflation of different kinds of dread: … of being unable to identify the tenses of some familiar verb; and what might be termed moral dread, the deep fears that can accompany the awakening of some acute adult moral consciousness. [1]

But I think Conradi here fails to see what you mean is essential in the poem, its obsession with the fact that dread is conflated because the word and feelings it connotes change their configuration to each other, and hence the meaning of the word, for a person over time and during continuing moral development. He misses it despite the fact that he does point to Murdoch’s belief that Fraenkel was aware that Agamemnon is a poetic formulation of how moral wisdom depends on facing the dread of ever deeper suffering that come upon us in the passage of time, deeper at least than public shaming in a university seminar. He points to the fact that Murdoch used Fraenkel’ obsession with the choric Hymn to Zeus in Agamemnon as a model of progressive moral learning in her early fiction. [2] In the end, his reading suffers from knowing the developed themes of Murdoch’s phosophy and not taking into account her deeper personal self-examination in the poem. In fact, this is this that makes her a better poet than Conradi allows.

In my reading of it, admittedly, before I revisited Conradi’s treatment of Murdoch’s flirtatious play with Fraenkel, the poem plays games with time. It is no mistake that it is knowledge of an aorist tense in Greek language in which Murdoch fears being found deficient, for the worst is a tense that has a special relationship to a past considered as over and done with, completed and without chance of resurrection. Wikipedia has a useful description of the tense:

In the grammar of Ancient Greek, an aorist (pronounced /ˈeɪ.ərɪst/ or /ˈɛərɪst/) (from the Ancient Greek ἀόριστος aóristos, ‘undefined’) is a type of verb that carries certain information about a grammatical feature called aspect. For example, an English speaker might say either “The tree died” or “The tree was dying”, which communicate related but distinct things about the tree and differ in aspect. In ancient Greek, these would be stated, respectively, in the aorist and imperfect. The aorist describes an event as a complete action rather than one that was ongoing, unfolding, repeated, or habitual.

The vast majority of usages of the aorist also describe events or conditions in past time, and traditional grammars like Smyth’s A Greek Grammar for Colleges introduce it as one of three secondary tenses expressing past time.[1] However, it is often idiomatic to use the aorist to refer to present time. For example, ‘Go to school today’ would be expressed using the aorist imperative, since the speaker is giving a command to do an action at one point in time, rather than ‘Keep going to school’. Some modern linguists describe the aorist as solely an aspect, claiming that any information about time comes from context.[2]

Even used idiomatically as a present tense, then, the aorist refers to actions able to be completed at one time that do not require further time in order to completed, and,I think, ones that can not change their meaning when repeated or continued over time as I thin the verb ‘to rad’ a book. It is often as an aorist that people use the English verb, ‘read’ (in English English pronounced ‘red’), meaning by ‘I read that book’ that being completed once it does not require reading again and that the process of that one reading is completed, not revisited even in memory.

The agency of continuing time is brutally refused by the aorist tense, but look at the context of time again in The Agamemnon Class 1939 and consider the significance of the dating of the poem’s title written after the long duration that led to 1977 when it was published.

Do you remember Professor

Eduard Fraenkel's endless

Class on the Agamemnon?

Between line eighty-three and line a thousand

It seemed as if our innocence

Was lost, our youth laid waste,

In the pellucid unforgiving air,

The aftermath experienced before,

Focused by dread into a lurid flicker,

A most uncanny composite of sun and rain.

What exactly is the reader asked to ‘remember’? And to answer that question we need ourselves to note that the primary addressee is given in the poem’s subtitle as Frank Thompson, who was killed by a Nazi firing squad in 1944. We have to get far into the sentence to find that what we remember is the ‘aftermath experienced before’, which can only refer to the sequelae in the future that we have already experienced in the past. It is the clearest indication that what it means when we ask someone to remember is definitely not a completed action of memory, a memorial, but a continuing and changing experience. In the very part of the poem where ‘dread’ leaks to focus and clarity (becomes pellucid’, which suggests, as I will say again later, both the bright concentrated beam of light shining on something and its sudden comprehensibility, what is focused is a future we have already experienced as a past snd will continue to do so. The past tense of the verb ‘to remember’ is always a past imperfect tense, is never ended or ending.

And then look again at the remembered class, not only what it was doing but is still doing: remembering a reading of Agamemnon. But teaching the young, even those at Oxford University, how to read, which Fraenkel was forced to do and Murdoch chose to do, whether reading texts from the classics or philosophy, or both since Murdoch’s specialism was in the philosophy of Plato, can be a thankless task. The past is a bore to the 19 year old usually.

That might be so if it is a mythical or historically veifiable past, not lost under the weighty blanket of many years. Note this, for instance, which queries might be interested in the Trojan War from which Agamemnon returns as a war hero, carrying with him fthe future cries of Cassandra,the princess, and prophet of destruction, of Troy as his booty. She in the play will be murdered with Agamemnon by the latter’s wife, Clytemnestra, as all along predicted by the said Cassandra; what is that but ‘The aftermath experienced before’. There are no teachers who reach a certain age who will mot recognise the following truths about the past we try to share with the young:

The disputed tomb of Hector, hero of the Trojan royal family

What was it for? Guides tell a garbled tale.

The hero's tomb is a disputed mount.

What really happened on the windy plain?

The young are bored by stories of the war.

Homer is associated with describing the coastal plain between Troy and the sea as a ‘windy plain’, but a poem written in the 1970s is also recalling the war that was declared in 1939, to be called the Second WorldWar and already boring the young who knew nothing of it, though it is not legend but relatively recent and historically verifiable. So Murdoch must have been capable as an older lady in 1977, but in 1939, she and Frank Thompson sitting in Fraenkel’s class were 19. Conradi tells us of her fascination, perhaps even submission to Fraenkel, but this was in the same year in which, for a significant lump of the year, she was involved in the student theatrical ventures chronicles in diaries published by Conradi too. [3]

My contention is that I read something else in the opening of the poem which is the substratum of the recaptured feelings of the 19 year old Iris Murdoch and Frank Thompson, each contemplating a relationship with the other, if not necessarily a monogamous one at least on Iris’ side for she was at the same time flirting with Fraenkel, of boredom at the need to sit the two hours – the classes were held between 5 and 7 p.m. – of the next Agamemnon Class. After all Fraenkel, however scholarly, was a man so little confident in his command of the English spoken and written in his land of exile that other scholars were still supporting him to translate his German text, which he started to work on in 1925 in Germany with a view to academic publication there. At the age of 19, it must have been a mixed experience for the radical and eager minds of Iris Murdoch and Frank Thompson (she trying even up to 1940 to persuade him to join, the Communist Party of Great Britain, of which she was already a member, even when in 1940 the party line remained that Hitler and Stalin were intent on liberating Poland by invading it.

Imagine living in the space of gestation of the ‘Teutonic monster’ pictured above, afraid and in awe of an unusually stern scholar already tested against Fascism and survived. Then think how such experience lived in the memory where Iris was both potentially already bored by what the establishment said about the necessity of the Second World War and capable of feeling it akin to the Trojan War. There is certainly a formalised prosaic character in the precise naming of Fraenkel using his title, Professor, and the description of his class as ‘endless’, the doesn’t take into account the lively personal interest teacher and student took in each other, verging on the sexual described by Conradi. No-one at 19 has not watched minutes time pass in a gathering where every young feeling has grown old and life seemed wasted – not only for the duration of the event but for, what seems to young souls, ‘forever’. That is what it means to feel when we experience something ‘endless’, as so boring that time itself seems to have stopped and promise no relief from what we are enduring.

However, the class, we have already seen, seems ‘endless’ for another reason (and a poem about it even extends its memorial life as a living thing capable of being re-read forever by successive readers). The poem’s opening is heavily and ironically ambivalent, capable of expressing the sense of an event that goes boringly on and on … and yet capable of turning that longue duree into something much tighter – that bright focus provided by a surprising light indistinguishable from the fear it evokes, that I mentioned above.

Bored students at university

Let’s unpack the extremes of its binary ambivalence. First, it evokes the feel of lengthy duration whose slow tread down a weary road of literal translation and abstruse philological inquiry is caused by boredom and produces more of itself as it proceeds (especially the case in the plod of ‘Between line eighty-three and line a thousand‘). Those line numbers are surely purely random, though both, I think, occur mid-way between choric lyrics. Perhaps youth is lost precisely when you dread the step between each line covered in that class and the dishonour, it does to the time available for living that seems to young people so precious and not to be wasted.

Second, it promises that in such bland diffuse and possibly distorted stretches of time there may be moments where time tightens into a focus on the bright and comprehensible – the spotlight of the ‘pellucid’, even though what is made clear is something ‘unforgiving; in its implications for our lives as Fraenkel was unforgiving of philological and grammatical error. Such revelations are dreadful. Nevertheless what we dread at 19 is not what we dread later in our lives (in 1977, Murdoch was 56 and Frank Thompson had been dead for 33 years).

At 19, it can be devastating dreadful if we are conscious of a first love experience, although Frank is only a fictive first love to Iris surely, that threatens to disable us in ‘incinerating crippling flame’. But equally at 19 we might wonder how the story of a remaining Trojan War hero can fascinate us when war across Continental Europe became a dteadful fact in our own contemporary moment, as the poem suggests it did – perhaps by twisting the real history – during that class unbeknownst to its attendees at the precise time of attending.But then the ‘returning hero’ takes in the years between 1939 another turn, another hero who did not return from war (even for the short time Agamemnon did before his murder), Frank Thompson, executed by a Fascist firing squad.

In 1940 there was lot of moral weight hanging on Iris, or at least it might seem looked back upon and read again in the light of the reading of Agamemnon. For Murdoch then was locked in conflict between the Communist Party line that was then in favour of the appeasement of Hitler and Frank Thompson’s certainty that Fascism must be fought in Europe and his consequent enlistment, against Murdoch’s judgement. Her love for Thompson was compromised too by the building of a constitution locked into complex negotiations with a tendency to Love regardless of the normative boundaries to that tendency like monogamy, sexual loyalty, fixed sex/gender/sexuality identifications – all of which were fluid (the subject of my next blog on these poems) in her. Yet in the interim Murdoch was certain that she learned the ‘sin and pain’ that was alien to the 19 who dreaded boredom more than the ‘moral dread’ of both of those things. This is how she expresses the shallowness of dread at age 19 for people of her entitlement, beautifully I think:

The spirit's failure we knew nothing of,

Nothing really of sin and pain,

The work of the knife and the axe.

How absolute death is,

Betrayal of lover and friend,

Of egotism the veiled crux,

Mistaking still for guilt

The anxiety of a child.

But later in our life, we might learn to reserve our dread and guilt for events of more heightened events than suffering a long seminar or embarrassment at it or even less immediate tragedies where the ego alone is bruised. We learn that we can collude in enormous loss and / or death, perhaps even mass loss. And, of course, that class was in 1939, and it appears at the precise time – occurring within the duration of the class, of the outbreak of the Second World War, a war which would lead to the death of Frank Thompson in action. And the world of sin and pain could have been read in Agamemnon had these 19 year-olds had the maturity. It was what the higher motives of Fraenkel – when he wasn’t lost in egotistic desire to grope his students (which some of whom – Iris included – seemed to collude in) wanted them to learn from reading the great book he was helping them to begin a lifetime of forever reading. Here, quoted by Conradi, is how the man in The Unicorn, who Conradi argues was modelled on Fraenkel, Max Lejour, talks of rhe Zeus chorus from Agamemnon.

Zeus, who leads men into the ways of understanding, has established the rule that we must learn by suffering. as sad care, with memories of pain, comes dropping upon the heart in sleep, so even against our wills does wisdom come upon us.

Here then is the wonder and beauty of the poem for I think Conradi is right about it being about the variations of dread in Murdoch’s thinking, but I think it is that by virtue of the fact that we only understand the suffering in a book housing Aeschylus’s play, as it and the contexts of our reading it get reread in the continuity of our life, with its words charged by the real suffering in our adult lives. This is not to say that the young don’t suffer but that their suffering, if they are entitled and privileged as Murdoch was in youth, was not so great as later events, and reflection on one’s conduct in such events, would show her to be possible.

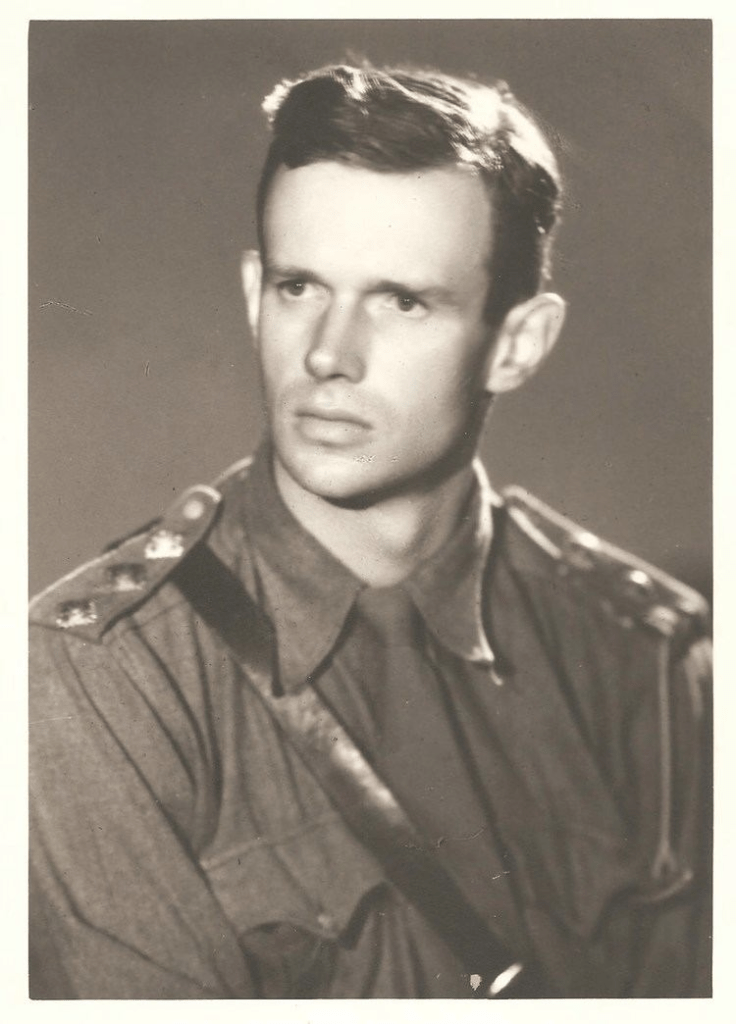

Frank Thompson: Anti-Fascist soldier-hero

Reading the poem fully is posited on a belief about reading experience, that is also its subject. That belief insists we only read, only know the fullness of what we are reading, when that personal, interpersonal the historical situation of that time and space experienced in a continuum interpenetrate the process and content of reading and develop the text as a memory. There is pain in addressing this poem first to Frank Thompson, the ‘you’, who:

Are all pain and yet without pain

As is the way of the dead.

I think some of that pain is the shared pain of the play being read, for Thompson’s ‘hero’s tomb’ was also a ‘disputed mound’ now, a war hero whose story bores the young but ought to matter to Murdoch, ought to have mattered more when he was alive and with her and both were young in that Fraenkel class, dreading mainly being caught out misinterpreting the tense of a Greek verb.

So, for the prompt question, I am reading ‘right now’ the book that contains the poem (I will write more on the whole book another time and what it adds to our understanding of queer history) but the poem is about the facrt that we never read a book once but are always re-reading (sometimes only the memory of reading it in a particular context). A good book is being read FOREVER (then, now, in the future), its tense when we speak of it the past imperfect not the aorist.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxx

__________________

[1] Peter J. Conradi (2001: 121) Iris Murdoch: A Life London, Harper Collins Publishers.

[2] ibid: 120, citing The Unicorn, The Time of the Angels, and The Book and the Brotherhood.

[3] See part 1 of Peter J. Conradi (Ed.) [2010] Iris Murdoch: A writer At War: Letters & Diaies 1939 – 1945 London, Short Books.

[4] Cited by Conradi 2001 op.cit: 120