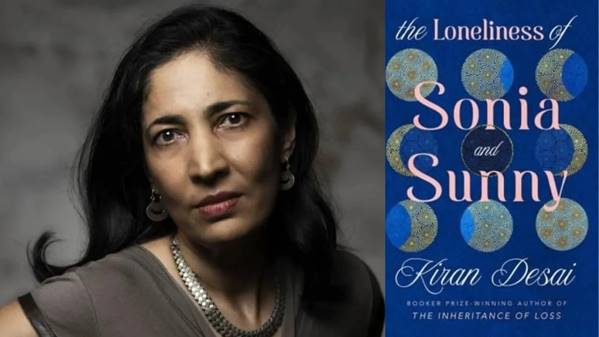

At one point in the latter parts of The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny two women, Babita and Sonia, alone in separate rooms in a huge mansion from the Portuguese era in Goa, an era established from 1510, that has all the characteristics of a Gothic Castle of Otranto, speak between the sound-porous walls of the terrors of their sleepless night. The elder woman Babita (the mother of Sunny from the novel’s title, thinks that the fears of Sonia sound like she had ‘caught hold of an invisible beast’ of which neither woman knew what ‘it looked like exactly’: ‘but it peeked up here, then it peeked up there, a nose, a tail, a threat, a sign – they were following and being followed by a dangerous enemy’.[1] Critics of this novel concentrate so much on the romantic and/or career roles of Sunny and Sonia in it that they pay little on attention to the ‘large, loose, baggy monster’ that inhabits it so loosely, largely and shaggily and insists on meaning something and / or many things, and thus miss the point of this novel’s achievement, an achievement nevertheless that does not make it easy reading.

I wonder if critics work too fast to express their honest feelings about a work so large in every which way in which the ambition of a novelist might be expressed as The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny. Its vastness must, some think, be a flaw, though when expressed by such by Malavika Praseed in Chicago Review of Books, in relation to the ‘supporting cast’ of the novel other than the titular ones, there is also a tentative get out clause:

From Sonia’s father’s helplessness to Sunny’s mother’s insistence on provincial White manners, they serve as necessary deterrents to our main characters’ happiness, but also dominate large portions of the narrative. Succinctly put, they are tiresome to read and in a tome such as this one, nearly 700 pages, the mind looks for places to scale back.

Other aspects of the novel are not necessarily flaws. Sonia and Sunny is slow paced and does not contain the expected narrative beats of a romance, but that is because its scope is much broader and less tangible. Pages and pages of the novel are devoted to lush, immersive descriptions of Delhi and Goa and New York City, which can distract some readers but serves to create an almost fantastical environment.[2]

Finding flaws in writing is a favoured task for critics but is done at the cost of asserting that the reactions of the critic represent some kind of norm of what a novel should look and feel like to all readers. Slow placing and large portions of what is treated as non-essential characterisation of minor characters not related to the central ‘romance’ may seem related but Praseed clearly thinks that while what they see as thin but lengthily repetitive characterisation is dubbed ‘tiresome’, the creation of a ‘fantastical environment’ that equally slows the pace is not. In contrast Alex Clark in The Guardian attributes the novel’s length to a dual focus: ‘Critically, it is a novel as much about work as it is about the relationship between Sunny and Sonia Shah, …’. But, in saying that, Clark also argues that, since Sonia’s work includes so much about the manner in which stories about India must differ, and yet not differ, from the Western tradition she reads heavily in, she tells almost exotic – or orientalised- myriad stories (as does Sunny) revealing difference of character, setting and plot in Indian story-types, solving the contradiction ‘in this immensely entertaining and generative novel’ strategically attempting ‘to dart continually between modes of representation and register’.

Clark therein also shows that there must be something really important about the sheer mass and duration of the novel that includes amongst those modes the Gothic novel and the ‘noir crime plot’, and yet there is clearly also something, Clark’s own prose suggests, to feel uncomfortable about here:

Capacious and shape-shifting though the novel is, filled with subtexts and shadow narratives, it is still a challenge to hold the contradictions and demands of multiple identities.

The ‘capacious and shape-shifting’ is, after all, a kind of character in the novel, and for me it represents the psychological reality of the novelist’s struggle to contain the uncontainable potential of the multiplicity – of stories, characters, settings made possible by the novel as a mode. I have, as the critics do, compared it to Western Gothic fiction but in the novel it insists on roots in Tantric theology or the Eurocentric take on the Tantric brilliantly analysed by Indra Sinha, no mean novelist and Booker contender of the past.[3] However the shape-shifting between categories of sex/gender, animal / human and foci of energies In Tantra is by no means for the purposes of regulation, as the British Raj saw plainly enough. Now Clark almost makes the same point as myself in worrying about the de-centred narratives of the novel, when asking, on Desai’s behalf its latent questions about the necessary form of her novel, especially:

… ; … how the form of the novel, created in the European consciousness, can complexify itself to take account of an accelerated fractured modernity [4].

My own study of the development of the novel, born of teaching over several years a course on ‘The Novel’ in higher education, suggests that Clark oversimplifies here by confining the issue of fracture to modernity, however fast is its pace relatively to earlier history. The novel is definitely a product of European consciousness but is also one that has faced issues of how to represent the worlds it choose to represent, and how and what worlds to choose in order to represent them is as very old one, creating as many problems for Cervantes, Richardson and Fielding as for the norm in the novel associated with the person usually called the Master of the aesthetic form, Henry James.

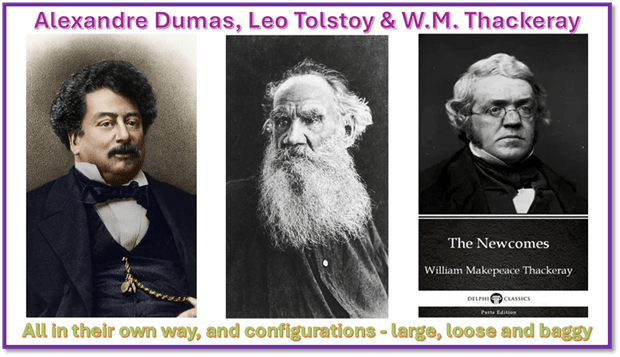

James most famous formulation of his own theory of the novel as a form is probably that in his ‘Preface’ to his 1921 novel, The Tragic Muse, where he points out the danger of the multiple foci of interest the novel as a form has always invited, but especially by the accidental forms of publication drivers of the nineteenth century: the serial novel, as used so often by Dickens, and the three-decker novel, that helped form Thackeray and George Eliot. When James too his aim at the nineteenth century form, which he unflatteringly called in this preface ‘large, loss, baggy monsters’, his concern was that it was too loosely focused a form in the nineteenth century – it had no centre on which to focus so replete was it with multiple foci of approximately equivalent interest, aimed not at aesthetic but popular standards. This was not just a matter of quality – it applied as much to Lev Tolstoy as a novelist, he believed, as to Alexandre Dumas and William Makepeace Thackeray. Speaking of The Tragic Muse, published serially itself, he spoke, in a more complex way than my edited version below shows, of the danger of a divided focus, whether the division was binary or multiple. It was the sin he found too in George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda.

… I had a mortal horror of two stories, two pictures, in one. The reason of this was the clearest—my subject was immediately, under that disadvantage, so cheated of its indispensable centre as to become of no more use for expressing a main intention than a wheel without a hub is of use for moving a cart. It was a fact, apparently, that one had on occasion seen two pictures in one; were there not for instance certain sublime Tintorettos at Venice, a measureless Crucifixion in especial, which showed without loss of authority half-a-dozen actions separately taking place? Yes, that might be, but there had surely been nevertheless a mighty pictorial fusion, so that the virtue of composition had somehow thereby come all mysteriously to its own.

It is worth halting our reading here to look at the Tintoretto canvas he refers to, which like all the great Tintoretto epics contained multiple stories, each viewable from different pictorial perspectives and many with varied length from point of view to vanishing point of the particular perspective. Frankly compositionally, the painting struggles, utilising the Christ figure as its central focus – but one continually disrupted by the eye moving to different directions, and depths, even in finding a level ground on which figures stand to perform their particular sub-narratives, but it does, James suggests, have composition.

The Crucifixion of Jesus By Jacopo Tintoretto – The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=159448

In continuing, James looks to the danger of unregulated shifts of narrative point of view and focus, not only in the achievement of beauty of form but also of artistic ‘meaning’. He cannot find such meaning in War and Peace (which he calls Peace and War, perhaps to demonstrate his discombobulation) for too much serves other purposes – such as the demonstration of the degree to which the apparently ‘arbitrary and accidental’ is necessary to create social realism or other effects of the long novel, such as truth to the very feel of ‘life’ in the work.

Of course the affair would be simple enough if composition could be kept out of the question; yet by what art or process, what bars and bolts, what unmuzzled dogs and pointed guns, perform that feat? … A picture without composition slights its most precious chance for beauty, and is, moreover, not composed at all unless the painter knows how that principle of health and safety, working as an absolutely premeditated art, has prevailed. There may in its absence be life, incontestably, as The Newcomes has life, as Les Trois Mousquetaires, as Tolstoi’s Peace and War, have it; but what do such large, loose, baggy monsters, with their queer elements of the accidental and the arbitrary, artistically mean? …[5]

The aim of art is not to simplify but to focus on aesthetic meaning through the composition of the whole picture or story into one integrated whole, its aesthetic meaning, rather than other multiple and diverse categories of meaning. Moreover, it is the multiplicity and diversity that the British Raj feared in Tantra, of both sexual practice, bodily plasticity and unregulated power from the bottom of society up, releasing energies unfriendly to the regulation of the status quo from the top-down in hierarchical political cultures. This idea is not a matter of modernity then as Clark would have it (or, at least, not that alone). This is why, I think, this novel is set in the past – the 1990s and early 2000s, long enough according to Meghna Pant, a literary correspondent for Vogue (India) who interviewed Desai about the novel, that they might ‘feel like a fossil to younger readers’. Desai’s response to Pant is interesting and is evidence that her intention was to visit a time somewhat earlier than the current time.

Desai’s stated defence of the backward look that the novel takes is that “loneliness hasn’t changed. If anything, it has become more profound. The social media generation longs for depth and stillness” Yet, intentionally or not, the source of that ‘depth and stillness ‘ she feels young people must be missing now is illustrated by an attitude to reading literature. She wants for that younger generation is that they might ‘find what she once did growing up: “That feeling of vanishing into a book, of letting it become your world.”[6]

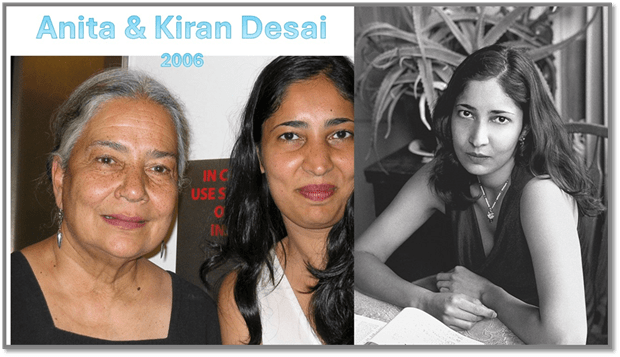

Such a thing is the more possible if the events are at a distance from the present, if within one-generational memory – things like the events leading up to the Gulf War and the identification in the West of a supposed Muslim threat to world order, that included the tit-for-tat nuclear armament of both India and Pakistan in fear of each other, but for India becoming a means of cementing Western inclusion as a nation. The idea of ‘vanishing in a book’ requires of course a book extensive enough to get lost in, and one that wasn’t always guiding you to some central focus. In my view it is one of the motivations of the book to ape the ‘large, loose, baggy, monster’, where the ‘accidental and arbitrary’ keeps cropping up to consume a reader and sets its course of pursuit somewhere inside its own loosened, vast highways and byways. And yet the writer is continually reminded by the ‘mortal horror’ of a master like Henry James that they need to prove themselves by creating novels with the finely tuned composition of a James late novel, a novel like Anita Desai’s Rosarita for instance – which fits all the themes of daughter Kiran’s novel in a very tight focus (see my blog on this here).

From left: Anita and Kiran Desai in 2006 (Mikki Ansin/Getty Images)

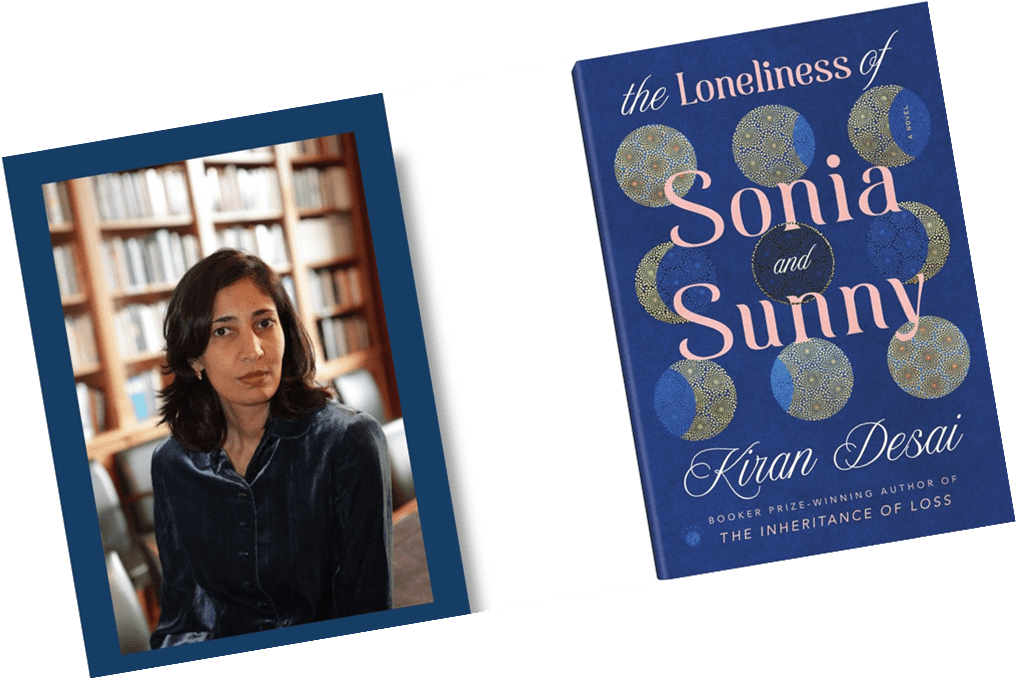

I take the ‘monster’ that Henry James posited literally in this book, though is sometimes a ‘demon’, ‘beast’, ‘hound’ (like that of the Baskervilles) or even merely unlimited darkness in pursuit of one, to swallow one whole or in chewed up fragments within it. It took Kiran Desai between nineteen to twenty years to complete this novel, started soon after The Inheritance of Loss won the Booker Prize. She claims to Pant that the entire time, when not caring for her increasing frail mother, Anita Desai the novelist, she was writing and refusing the usual perils of having written one Booker winner already:

What does it mean to vanish? Not metaphorically, but in the brutal, everyday sense: no Twitter threads, no TED talks, no think pieces on the publishing industry, no lit-world sightings. Just a woman at her desk with a dying laptop and a half-boiled idea, showing up to the page every day for two decades. For most writers, this would be career suicide. For Kiran Desai, it is craft in its purest form.

Vanishing may not be intended as ‘career suicide’ but for some writers it has that effect, and even if not suicide – for a novel appears after it that was already Booker short-listed before it emerged – it pales and pines on the edge of potential failure for a long time, for writing is a lonely business even when one takes that ‘loneliness’ and its various aetiologies and types as one’s subject-matter. Fiction is fearsome. Does not James even hide under his elegant mannered prose that ‘mortal horror’ of a story that fails to meet its purpose like a wheel without a sustaining hub, or a person without a spine: ‘… I had a mortal horror of two stories, two pictures, in one. The reason of this was the clearest—my subject was immediately, under that disadvantage, so cheated of its indispensable centre as to become of no more use for expressing a main intention than a wheel without a hub is of use for moving a cart”. If Henry James can say this so can Desai locate the writer’s lot, especially over the long duration of the creation of serious art, as located in the loneliness of ‘human shame’ and ‘human fear’. Hear Pant quizzing her again:

“Fiction,” Desai tells me, “always begins with one person on their own, with their human shame and their human fear.” In this age of algorithms and attention economies, that feels almost subversive. In Desai’s work, the spectacle is never out there. It’s internal. Her characters are often emotional immigrants, displaced not only from countries but from themselves. Sonia, a drifting art critic with a fractured family and failed love affairs, and Sunny, a Delhi boy turned New Yorker haunted by ambition and maternal guilt, are two such aching centres. They don’t seek redemption. They seek to endure.

In that, they echo all of us, searching for meaning in the quiet margins of survival.[7]

It might appear here to you, as it certainly does to me, that the ‘large, loose, baggy monster’ might be more fearful than its scruffy slightly comic description in James suggests (somewhat like a salivating tail-wagging St. Bernard hound) and that for a writer, the consequence of the uncertainty of achieving some aesthetic (or life) goal in writing can be cause of suffering for both Sunny and Sonia, but particularly Sonia and to her mental peril. And Pant feels that she knows that feeling in Sonia and Sunny too.

The novel certainly associates the feat of writing with a struggle against the pursuit by and the following of a monster, with even our defences against being so inadequate that we take on its characteristics. In terms of human emotions the pursuit of art, is also being pursued by art’s cost – loneliness. This takes the neurotic form of an all compelling darkness in the semi-psychotic thinking of the painter Ilan Foss Torness who fears the shadows that other people label uncanny, and accepts the unreal (or surreal) only when he knows it realised in an entirely fictively overworked Mexican isolation.[8] I have in my title noted the beast that pursues both Babita, Sunny’s Clytemnestra of a mother, and Sonia in their separate loneliness in a Portuguese mansion in Goa in a liminal world where insides and outsides, where Sonia thinks Babita will think that she has a ‘screw loose’. Here it again:

Babita did not think Sonia had a screw loose. She thought that Sonia had caught hold of an invisible beast. What the beast looked like exactly, they did not know but it peeked up here, then it peeked up there, a nose, a tail, a threat, a sign – they were following and being followed by a dangerous enemy It sent its emissaries.[9]

The odd thing is that this beast is the kind of baseline existential loneliness of a longing for independence that connects both women, a loneliness somewhat tied in with enforced dependence on men, however one fights against it both are betrayed by that ‘nose’ and ‘tail’ that gets everywhere in its animal prowling. But when Babita retells that story to Sunny, she tells it focusing on the fact that for Sonia, the monstrous beast, for her a ‘ghost hound’, she struggled with had to do with the necessary difficulties of dealing with her driver as a writer – that comes to play even when writing on Goa or kebabs, but especially novels. And here the beast is very like the one in Henry James, with the same ‘mortal terror’ of loosing hold of the centre of one’s writing focus:

Honestly, it made sense in middle-of-the-night ramblings, but in the morning I was not sure what she meant. Maybe it was a metaphor of some sort. She said she was trying to write a book but she can’t put the center in the center because the center is occupied by a ghoul that has the same eyes as a dead man who assaulter her in Sardar Samand.

A modernist like James would have recognised the problem – trying to focus art when life seemed fragmented and senseless in its large, loose, and baggy monstrous way. The idea is in Yeats writing about writing too (in The Second Coming), where what is created might be Christ or the Beast of the Apocalypse, roaring at its failure to be seen whole:

… Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere The ceremony of innocence is drowned; … … : somewhere in sands of the desert A shape with lion body and the head of a man, A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun, Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds. The darkness drops again; but now I know That twenty centuries of stony sleep Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle, And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

In Sunny’s elaboration of his mother’s craziness, as he says he sees I when she tells him of that night with Sonia, whilst thinking crazily himself, he is to blame for the beasts that continue to follow both women as they are forced to follow them, so that no-one knows who is ‘hunting’ whom. Sonny sees that Sonia has taken on Sunny’s pursuing ‘darkness’, that which drives his art, ‘incarnated’ it into a blood demon, and invested itself in him too – despite the paucity of his own reportage like writing, he still thinks he looks for the creation of his own bildungsroman life-story: ‘He had thought he was hunting a life story, but a life story had been hunting him, calling upon him to play his part’.[10]

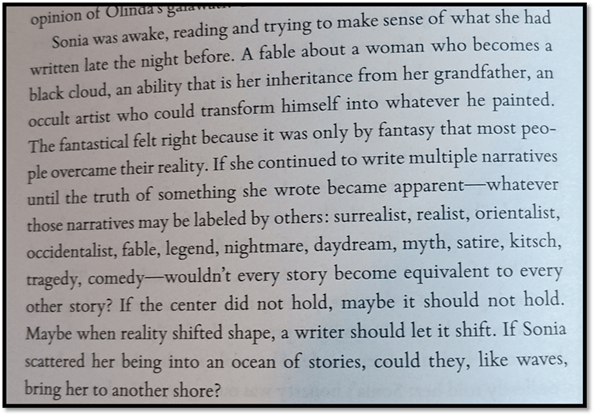

Later still, Sonia elaborates her own beast with its hunger for the ‘indispensable centre’ (James’ term) of the best stories in order to fragment them as a problem with fixing on a single narrative and even on a single genre of narrative types such that her writing is a beast too multiple – a ‘large, loose, baggy monster’ indeed, which even raids Yeats term for the missing centre: “If the center did not hold, maybe it should not hold’. But here she embraces the monster – no longer the demon-hound that emerges from and back into the sea, but the vastness of a central ocean of multiplicity – the modern deconstructed novel, or more appropriately the Indian diaspora novel since the innovations of Salman Rushdie.[11]

Desai’s novel is patterned around certain symbols, like the person as ‘black cloud’ above I believe, but I will leave it for others to trace them more fully – symbols already culturally associated with one kind of solitude, such as that very ‘cloud’ that Wordsworth identified with his own isolation and mentioned by Dadaji, Sonia’s father in the first chapter of the First part of the novel (subtitled ‘Lonely Lonely?’) when he considers how ridiculous it is that his daughter Sonia should feel lonely in, of all places, the USA:

Whenever Dadaji thought of the Wordsworth poem he had been taught in school – I wandered lonely as a cloud / that floats on high o’er vales and hills – the line struck him as so ridiculous it made him throw back his head and guffaw so hard his upper dentures fell down with a smash’. [12]

What a Dickensian way of introducing one’s emotional symbols is this, yet so subtle that when Ba, Sonia’s mother, consigns herself and her husband to solitude apart from each other, she chooses to live alone in Cloud Cottage. We should look out for clouds interred in the writing, but the main one is associated with the king of demons in the novel – the ‘faceless’ figure, with ‘cracked void, a broken visage’ instead) of Badal Baba, Hermit of the Cloud’, found by her grandfather in the Himalayas and given to Sonia as ‘protection’, or so she feels until she learns more about their nature. Search as I might I cannot find Badal Baba as the name of a Tantric demon or rakshasa but its meaning in Hindi is something like Dad (but instinct with respect and veneration as if for a spiritual teacher in Baba(बाबा )which it can also be) Cloud (babal (बादल) being cloud) and the only internet usage I found was for the Hindi rhyme explaining to children why clouds produce rain, useful knowledge for a country in which there is a monsoon season. Is Desai then being as playful with her ominous clod references as she is in describing Dadaji’s debt to Wordsworth’s cloud poem of loneliness.

Badal Baba is already associated with threat and loneliness then. Reading about him at first, I thought of the common run of defensive Tantric temple demons protecting the holy, replete with fearsome phalli like that in the collage above on the right. But her demon is indeed adapted further by Sonia’s consciousness and she deliberately associates it and the amulet in which it is enclosed with the emotions related to her writing: ‘Sonia kepi it open by her desk when she worked; sometimes she put a pebble or acorn before it as if it were a writing god, terrorizing her, inspiring her’ (my emphasis).[13]

Babal Baba however does a fair bit of metamorphosing in the novel such that he appears the very demons against which he protects – the dark that pursues Ilan and the demon hound from the sea (and from the Baskervilles – Sunny is reading Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles when he first sees Sonia – herself reading a modernist Japanese novel) that threatens both Sonia and Sunny. That Babal is the principle itself not only, and that in a minor way, of protection – but of the desire to transform in the same way as objects do in a dream is important to the nature of him in this novel. Badal can ‘be’ many things: at the same time one and the same object whilst being different things too until we wake up to to see him partitioned and in dispersal, each part sepate from each other. The novel becomes quite mystical (or comic depending on how you read it) at these parts – Tantric perhaps – when Sonia and her mother, Ba, carrying Dadaji’s ashes hear the tale of Ba’s father, who spoke to, and was spoken back to by, Babul Baba, in different sounds or voices depending on how Babul was named: ‘It made the sound of rain, or birds, or leopards, or the ocean, or wind – which is the same thing as the voice of a ghost. All these sounds are related’.[14]

The idea that mulitiple things are one thing, in Neo-Platonism as well as some South-East Asian mystical paradigms, could be the key to finding a centre in a thing of multiplicity – a large, loose, baggy, monster – but the answer depends on the art of the past (pre-modernist but go back a very long way in India and Mexico via different paths to different phenomena) as well as that of post-modern doubts about singular and centred realities.You get another hint of that in the shade of another baggy monster – a ‘monster bat’ large and spooky enough to be a vampire or flying ghoul as Sonia andher father listen to a singer wearing a black sari to protest the morbid and deadly dictatorship of President Zia in a Pakistan of my memory:[15]

Desai only hinted at the horror of facing both the solitude and the fear of aristic failure, with James’ masterly tones in one’s ear, rather nuancedly to Pant, saying:

Of course, such solitude isn’t always sublime. “It’s physical too,” Desai says. “You lose your stamina, your health.” Her eyes, she tells me, are failing. “I need to rest them now. Swimming used to help, but I haven’t been doing that either.” Her confession doesn’t carry the romance of the tortured artist, just the realism of a woman who has chosen the long road over the loud one.[16]

Everything here, even invoking the help of swimming (and having it turned into the subject of someone else’s vampiric art, applies to the characters in the novel as well as Desai but the drain on life is more attributable to the demons of the imagination – personal, social and transglobally multicultural. Similarly when Desai speaks of her mother, one wonders what semi-unconscious difficulties linger there in a novel where mother-child relationships are so fractured, not least by sex/gender and diaspora issues. Kiran says of Anita:

“She was the first person who read this book,” Desai says. “When I couldn’t see the shape of it, she could.” Their relationship has evolved from the literary to the literal; Desai now cares for her 88-year-old mother when she can, reading and writing in her home, an hour and a half away. “She never made me feel like I was competing with her. She was always a reader first, a little bit editor, but mostly, a mother.”

There is something circular and soothing about this. A daughter who once stepped out from the shadow of a legendary literary mother now returns to hold the centre. Both women, bound by books, reading, writing, solitude and an almost sacred rhythm of discipline. At one point, I ask Desai if her novels are escape routes from her own diasporic displacement. She pauses. “They’re not escape routes,” she says, “they’re the map.”

Now, in such a long novel, I hardly scratch the surface of the multiplicity of strengths in it but that is in part because I too am educated to look for ‘centre’ issues or debates. Even now I do not know if I have found them. What I am certain of is that this novel is important enough to be a Booker winner. It may pall on those who hate long reads and who yearn for critically edited narratives so it might not win, but in the end I hope so. It is the very opposite response to the next best novel on the shortlist in my view: Audition.

Bye for now.

with love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Kiran Desai (2025: 626) The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny London, Hamish Hamilton (Penguin Random House)

[2] Malavika Praseed (2025) ‘To Be Alone is To Be Understood: A Review of The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny’ in Chicago Review of Books (September 24, 2025) Available at: https://chireviewofbooks.com/2025/09/24/to-be-alone-is-to-be-understood-a-review-of-the-loneliness-of-sonia-and-sunny/

[3] See the introduction to Indra Sinha (1993: 11f.) Tantra: The search for Ecstasy London, Hamlyn.

[4] Alex Clark (2025: 53) ‘Worlds Apart’ in The Guardian Saturday Supplement (13.09.25) page 53.

[5] Henry James (1921) ‘Preface’ in Henry James The Tragic Muse Project Gutenberg edition 2006, Available at : https://www.gutenberg.org/files/20085/20085-h/20085-h.htm

[6] Meghna Pant and Kiran Desai ‘Interview: Kiran Desai on being shortlisted for the Booker Prize: “I can’t write unless I vanish”’ in Vogue India (24 September 2025) available at: https://www.vogue.in/content/kiran-desai-on-the-loneliness-of-sonia-and-sunny-being-shortlisted-for-the-booker-prize-2025

[7] Meghna Pant and Kiran Desai, op.cit.

[8] Kiran Desai 2025 op.cit: 42

[9] Kiran Desai (2025: 626) The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny London, Hamish Hamilton (Penguin Random House)

[10] Ibid: 631

[11] Ibid: 654, in photograph too.

[12] ibid: 5

[13] Ibid: 22

[14] Ibid: 587f.

[15] Ibid: 188

[16] Meghna Pant and Kiran Desai, op.cit.

2 thoughts on “A speculative blog on Kiran Desai’s ‘The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny’. My Booker winner.”