‘“Twa Boabs”, the man laughs. “A matching pair!”’[1] You wait forever for a queer Ayrshire Scottish artist intent on rivaling the phallocentric Robert Burns, then ‘Two Roberts’ come at once. This is a blog on Damian Barr (2025) The Two Roberts, Edinburgh, Canongate.

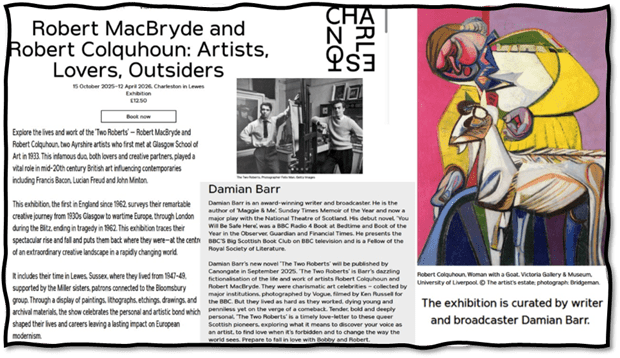

The power of Damian Barr’s novel The Two Roberts lies in its imaginative reinvention of an instance of queer coupledom in a time totally resistant to such a phenomenon. But inevitably, since I need to note my true responses to the experience of reading the novel, I ought to start with what to me was its weakness. It is a weakness overly focused upon given that novel comes out alongside a retrospective of paintings by Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun curated by Damian Barr, in honour of this novel’s publication in part, at the Charleston House Gallery in Lewes, named Robert MacBryde and Robert Colqhoun: Artists, Lovers, Outsiders. The publicity for that show emphasises (despite the ‘outsiders’ description) the centrality of these artists to a period whose memory is now dominated by just a few names, those cited in the publicity are ‘Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and John Minton’.

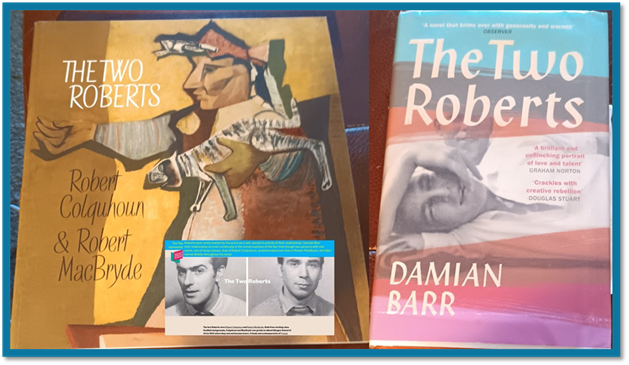

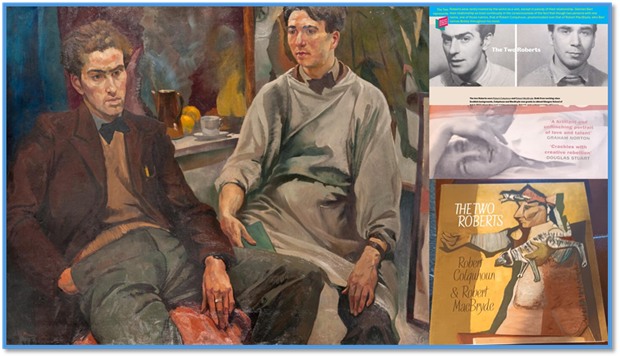

Though Minton might truly too now be described as an ‘outsider’ to the ‘mainstream’ (if not the queer) tradition of art history this does not apply to the other two names – at least currently. Those two names are giants in the ‘mainstream’, whilst The Two Roberts were last given major airing between 2014 and 2015 at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in a show that did not revive their popularity, despite the comprehensiveness of its holdings (the catalogue of it is shown above in the collage – on the left).

The contextualisation of Barr’s novel as another attempt to revive the names forgotten from what most recognise as the age of the figural tradition when it was at its most prone to attack by the claims of the abstract movement in art is where the danger of misreading and wrongly evaluating this novel, in my opinion at least, is at its highest. Even as fictionalised ‘history of art’, this is not a strength of this novel, rather a weakness though it might usefully allow some queer students of that discipline to queer a little more the canonical story of figurative art from the 1930s to the 1960s. I need to clarify my experience of the book understood thus rather than its actual achievement as a consciously created and creative novel in this mode was wanted in queer fiction (and the fiction of human relationships generally), that rooted itself in themes of intersecting identity categories, like class, local communal allegiance and recognition of status.

Of course it is true that this novel does have a dual aim, setting out both to queer art history and, what matters most to me, to sieve ideological notions of romantic love and the notion of security in the notion of ‘home-making’ through a setting sensitive to the history of queer sociality and romance. To be sensitive to that issue romance has to be written in the context of paradigms of the shaping forces of oppression of many kinds, not all hetero- or homo-normative.

But the weakness of the novel, it has to be repeated is that it gets waylaid by the need to authenticate the reality of the historical figures it takes as its dual subject, characterised by, to me, tedious use of scenes reconfigured to include all the bon mots of admittedly ‘greater’ norm-challenging artists and artistic patrons contemporary to Colquhoun and MacBryde. They are legion but include Peter Watson (but not John Lehmann sadly), Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Dylan Thomas, George Barker, Margaret Smart and the list ends inevitably with Ken Russell.

The greatest sour note for me amongst those scenes is that, set inevitably in The Colony Room Club in Soho (see my blog on that club here) in which Bacon’s famous line about friendship in its original cruel-camp setting is preserved in queenly aspic. But the piece is for me completely mishandled – dragged in for the sake of its well-known authenticity but drained of its genuine insight into the characters of Bacon, Minton, their previous relationship and their set of ‘sham friends’ and otherwise, all clustering around Muriel Belcher’s bar, as a small circle of people less celebrated than they thought ought to be their desert, continued to do until its closure:

Here is the gist of the scene with text omitted, just to get the main bits in:

… the exquisitely tailored arms and legs of Johnny Minton windmill over, dancing to the jazz only he can hear. … He sports a weathered sailor on each arm, splendid in their whites, … Muriel swats him away but Francis catches one arm and holds him while snatching the Dom Pérignon from Bobby, who watches as Francis tips the last of it over Johnny’s long sad beautiful face. …

“Champagne for my real friends, “ drawls Francis, kissing Johnny before pushing him back into the arms of the sailors. “Real pain for my sham friends.”[2]

That tale has been told so many times and so much better – even disregarding the edited version only exists above – with such more empathy for Minton (a truly tragic figure in our queer history – whatever his unfairness to this couple) that it rings like the ‘sham’ that the Colony Room excelled in and made into a way of life over the long evenings in which no-one seemed to have a home to which they wanted to return, with or without willing sailors in tow.

At least it served this latter purpose of illustrating a kind of symbolic existential homelessness (never real homelessness for most were well-heeled but certainly the case for the Two Roberts towards the tale of their careers) characteristic of the period. I think though that it is unlikely any reader’s mind will have drifted that way towards the theme in this brief narrative, even with Barr’s hint in his Acknowledgements section later that: ‘Home is at the heart of this novel – having space to safely be yourself, to be in love, to have a life’.[3] Told as it is in the novel, it just authenticates the setting of it in what we call ‘real’ history, as well as fiction: the dual purpose he sets out at the opening of the novel’s Afterword: ‘The Two Roberts is a novel but Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun were very real people and very real talents, …’.[4]

For me, the novel would have been better without all the ‘fact-based’ scenarios (but in fact based on rarefied gossip in the end) from other people’s biographies or the people, places and social gatherings on which that gossip is based. Truly it hurts me that I felt that about a novel I otherwise loved and that is doing so much more than recreating the times in with both Roberts lived in the art world such as it queerly was in the long drawn-out evenings in boozy dives that yet had a poignant significance for queer lives and their (in)visibility. The latter purpose is already well served by Daniel Coffield and biographies of Peter Watson, Bacon, Lucien Freud (though with only grudging queer content in the latter case) and John Minton. May be it affected me so much for I have read or heard the stories so many times with much more explication of the human significance in them, especially that of the humiliation of John Minton. But let’s leave that dark side alone and rejoice in what is the lion’s share of the novel’s text and its effects.

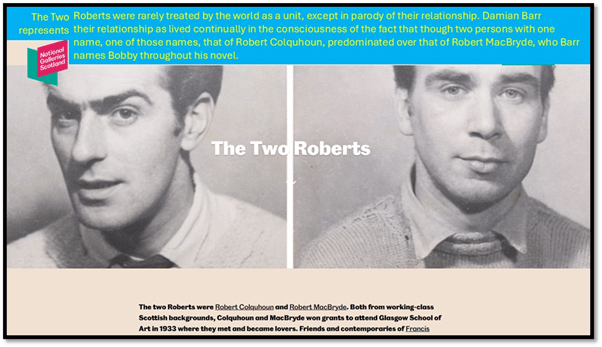

‘The Two Roberts’, a name coined contemporaneously to their lives, were rarely treated by the world as a unit, except in parody of their relationship. Damian Barr represents their relationship as lived continually in the consciousness of the fact that though two persons with one name, one of those names, that of Robert Colquhoun (named Robert throughout), predominated over that of Robert MacBryde, whom Barr names Bobby throughout his novel, was one in which progressively but from the beginning in smaller ways, Robert was empowered socially above Bobby. That this was so was not necessarily to either’s benefit, but perhaps the only option of characterising the relationship to those unable to think that even minds and hearts (nay souls) may work collaboratively.

Such queer couples can be a substitute for the psychodynamic paradigm of the ‘double’ or doppelgänger, or at least I will partly argue the case, and that links this novel to a great Scottish-European tradition in the novel explored at its best by James Hogg and Robert Louis Stevenson, where relationships of love are also ones of a strange dynamic soup of drives to self-defence, protection of the ashamed desire for otherness and power.

In my title I quote Morris’s naming of the ‘Boabs’ (imagine the central Glasgow pronunciation ‘a matching pair’) although this is less telling than the extension of the two into not only their artworks but the motive emotions and thoughts behind them when Bobby discovers that an upcoming retrospective exhibition will be a solo one for Robert alone: ‘But Bobby knows he’s in every one of Robert’s pictures and Robert knows it too and that is all that matters. One organism’.[5]

Twice (at the opening and closing of the book) they are described as lying there, ‘together, curled like commas’, though in the first opening instance also as ’naked in the nest they’ve rolled in the high grass’.[6] Their art-college year tutor allocates them a single shared studio in the College of Art going into the second year, one near his own, but none of the other learners is surprised when Fleming assigns them to share’: one venturing what he thinks of as a sneer: ‘Married’.[7]

Yet soon after this occurs, their differences cause tension that seems in part the result of over-heated over-containment.[8]

It is not that they are just complementary, but also that they share the same vision of the world, their knowledge too of the other a kind of self-knowledge. Yet complementarity is also often a kind of opposition where leaving and staying with each other are forces that reach stasis but not resolution of their conflict. At root where Robert feels anxiety about his artistic talent and might flee from it, Bobby holds it a ‘certainty’ that balances the anxiety, but again without resolving it. Similarly, they balance silence with volubility, self-consuming resistance to food to self-sustaining audible appetite , and stereotypical feminine with stereotypically masculine roles of care and self-care.

The issue of eating is an interesting one. Even on their first day at the Glasgow Art School Bobby eats the ‘piece’ his mother prepared for him, whilst Robert insists that ‘I don’t eat much in the day’. Whilst Bobby’s face is as young and rotund as the sun, ‘Robert’s a half-moon’, eaten away by the shadow of those around him. Robert is fascinated by Bobby’s mouth: ‘lips parting like they’re about to tell you a secret. They are much fuller than Robert’s own, which are as fine as the rest of him’.[9] Later, they visit London and eat in the aptly named The Golden Cock, where Booby orders chicken and orally savages it:

Bobby attacks his dinner. Robert picks at his fish, pale as a priest but hopefully tastier.

“You need to try,” says Bobby, mouth half full. “you’ve had nothing fae the train’.

Robert dimly remembers a sandwich somewhere around Carlisle. To appease Bobby he has a few more pokes at the cod before pushing his plate across the table – he’d rather watch Bobby eat.[10]

He ends watching Bobby consume ‘life’ and the means of continued living, turning himself into an eye fixated on a full mouth, enjoying its manner of filling itself as he empties out all there is of him, however fine and handsome the slender remnant. If Bobby is all appetite for continuing life somehow, then Robert is consumed from within by figures he remembers, not from his own more financially settled working-class life but from the accounts of the MacBryde family’s support for the Hunger Marchers of the 1930s that Bobby has told him stories about. Bobby does not feel those stories as inwardly as Robert does (or, for Robert’s sake, pretends not to, even though his was the primal vision). Perhaps the placing of these Macbryde family stories in a sharing of an assumed family socialist response to them what saved Bobby from mere identification with hunger as a form of human melancholy. This is not so for Robert, however, who changes; prompted by the tragic vision of the Polish Jewish migrant Jankel Adler, so much that all the inner tragedy of his own household (bound up in the early death of his sister) is redirected to those symbolic figures of WANT.

This frees something in Robert he dimly senses was trapped – sad figures began to populate his pictures, lonely even when they’re alone: young girls with the faces of old women, leaping cats scared by something humans cannot see, weeping wives holding each other for comfort so that they begin to seem like one long sobbing form. Hunger Marchers. Robert catches his mother’s tears, the blue tears he wasn’t allowed to cry for the wee sister who would never grow up. His figures bear the losses of all. They often have his own long face or Bobby’s full lips but nobody sees what they don’t want to.[11]

The uneasy balance between this introvert ‘neurotic’ (as the word was used then by early psychologists freed from stigma) response to the world and the relatively stable and extrovert in Bobby are yet more of the unresolved complementary qualities, that make the struggle between these two young men like the struggle within one organism; between the life and the death instinct, the desire to move on and the desire to stay put that they attempt, and often succeed, in sharing together. It is why they endure each other with enduring love and accompanying flares of hate, and why their qualities mix – otherwise why do Bobby’s pouty ‘full lips’ appear on some of the Robert-like hungry faces in Robert’s hungry long sad forms.

But other people see difference and, to help Robert, Bobby emphasises the difference by painting ‘objects’ in still lifes more than figures that are more likely to make a painter’s talents recognised, though often tempted to make these objects fleshly to the point of sexual sensuality (Robert calls one a ‘Still Life with Cock-like Cucumber’) and viscera: gaping gourds, wet insides, pips pouring from gouged flesh, apples ripening in the dark and all in colours that vibrate at the frequency of his feelings’.[12]

Little of that fullness described by Barr, as if intended at some psychologically deep level, is recognised, even by Robert, and it leads to Bobby’s talent seeming subsidiary and secondary to Robert’s: ‘The Two Roberts – twin stars, burning ever brighter, certain observers determined that one must outshine the other’.[13] Among the observers is Bobby, sometimes I think. However, it is also clear that Bobby either engineers or allows to persist situations where Robert will seem to outshine him.

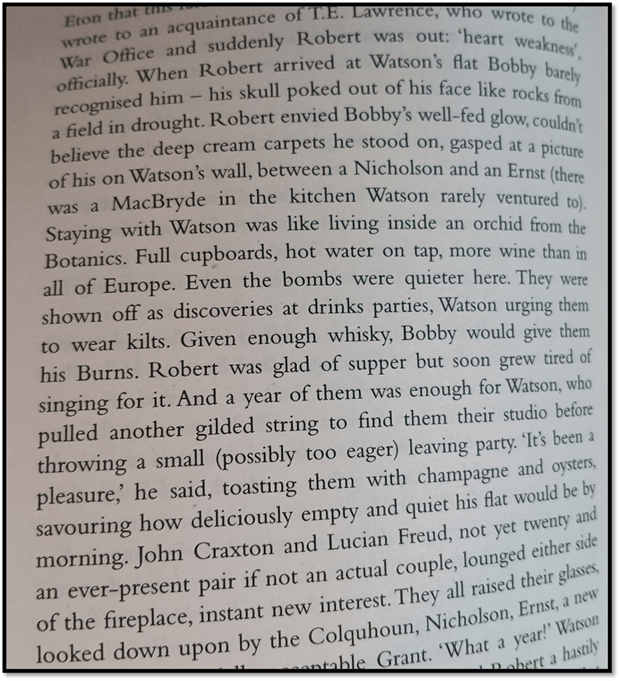

There is no doubt I suppose that Robert was to both their eyes the greater artist – whose work is lauded by people who know as better than Bobby’s from the moment Robert’s drawing of Bobby is hung on the wall of the Glasgow School of Art by Fleming but Bobby’s is not. But what astounds me is that if Robert’s star as an artist outshone Bobby’s the constant star of a poetic lover that shines most is Bobby, despite and even perhaps concomitant to his playful need to break rules of sexual constancy – in becoming Sasha for instance in order to interest more young men. When he is taken up by Peter Watson, a fact by the way, and installed in Watson’s home with all its riches, he uses this fruit of his sexual conquest to forward Robert’s ability to get discharged to honorably from the army uses Watson’s networks in the establishment and promote Robert’s art more than his own and eventually secure from Peter the money that allowed the couple to have a flat of their own on Bedford Street.

This section on how Robert’s art is pushed, without the pushing being obvious, to the front of Watson’s consciousness, I truly love. Robert’s pictures hang over Watson’s fireplace next to ones by ‘Nicholson and Ernst’ – higher flyers Ben and Max are intended by these sufficient artist surnames – whilst he stays in the kitchen like a good wifie who paints ‘as well’. Yet what Robert notices is the contrast between the fact that Bobby has a ‘well-fed glow’ and his ‘skull poked out of his face like rocks from a field in drought’:[14]

How the two men see each other and how they see themselves as seen by others is a major theme in this novel that I have not yet got my head around despite my stated intention to do so in yesterday’s chatty blog (available at this link).

A good novel requires I think that some things we fail to get our head around – they just ring with truth. In the Prologue chapter of the novel, relating to a visit by both men to Kildoon Hill, near-by Bobby’s family home, Bobby’s triumph is the achievement between the two men of a frank capacity to view each naked in the heart of natural rather than human artistic circumstances – the song of a skylark. Yet Robert sees the skylark not as a glory to match their mutual nakedness (and the fact that they have just had sex) but a ‘witness’ that might bespeak their sin in some human or supernatural court as queer lovers to a court in which their sexual love was illegal:

A skylark peels straight up – close enough to nearly catch – spilling its song over them. A blessing thinks Bobby. A witness, thinks Robert, reclaiming his arm and turning away.

Yet Robert is trained even in this page to see that his fear of detection as lovers is not natural, and that he sees their love, ‘as the law must’ in those days but ‘as the sun might’. It is a brilliantly written scenario.

Robert has never felt more exposed. Every cell in his body is completely transparent. To say nothing of his soul. He half-opens his eyes, and tries to see the pair of them, not as the law must, but as the sun might: two skites of pink-white-blue in a sea of midsummer gold. No more, no less.[15]

What the sun sees is the art of colour mix, and that is Bobby’s triumph, but is never a vision of queer love that can be afforded to Robert who only sees the world with eyes ‘half-closed’ by the need to see as the law does, and hence not see their embodied loving as a miracle. Bobby finds joy in lived life that Robert cannot. He is, in this brilliant summation written from the point of view of Bobby: ‘… maybe Robert’s always been like this? Quieter, held back, so the world can’t touch him. Robert is a shell Bobby wants to prise open and live inside’.[16]

This is a vision almost completed when Robert actually holds Bobby inside his great coat: ‘“Daftie,” whispers Robert, pulling him even closer, buttoning him into his coat and holding him there for a moment, for ever’.[17] Call me sentimental but the beauty of that tense contradiction at the end of that sentence for a moment, for ever’, tells me all I want to know about what Robert Browning meant when he said to John Ruskin (see quotation at this link): ‘I know that I don’t make out my conception by my language; all poetry being a putting the infinite within the finite’, and illustrated better in Two in the Campagna, that the infinite is a misperception of perfection in our finite selves and finite relationships, as true of queer love as any other.

Just when I seemed about to learn! Where is the thread now? Off again! The old trick! Only I discern— Infinite passion, and the pain Of finite hearts that yearn.

This discourse about loving as ever needed doing for queer coupledom and queer love generally, for queer people accept heteronormative views of our limitations too easily and fail to see ‘as the sun might’.

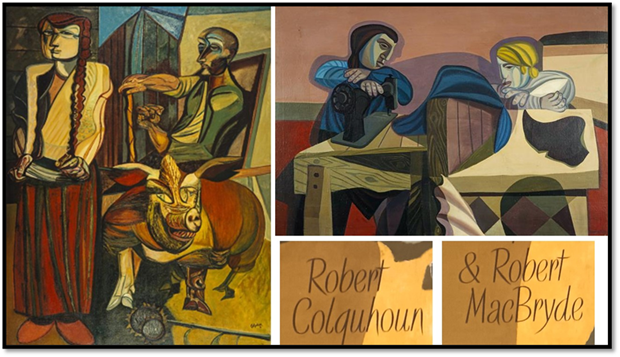

And if we compare the painters, in seeing the better art in Robert we see also a franker, more openly loving one in Bobby. There are similarities between the great Figures in A Farmyard By Robert and Two Women Sewing by Bobby: Robert sees the cruelty in the relation between the man and his daughter (or wife) in the foreknowledge of the pig, described in this novel as a ‘gurning pig, its face a miniature of Guernica’. Everyone knows this pig must die, and no-one sees much in the human family of hope, but Bobby’s figures – equally Cubist or Vorticist in their conception, have a very humanely constructed belief in the cloth-making and fuller, less torn and fragmented bodies.

I think I still believe that this novel works with a doppelgänger theme, but the two Roberts are only one Robert/Bobby in the fact that relationships require that self and other learn union from acceptance of difference. That’s all I have to say about it.

Bye for now

Love Steven xxxxxxxxxxxx

By the way the point about rivalling Robert (Robbie) Burns is made by Bobby’s Aunt Maggie (page 13) and Bobby sings Robbie throughout with especial emphasis at one point on Burn’s ‘obscene’ poem about cock size: ‘Nine inch will please a lady’, though Bobby did not refer the point of that to ladies at all.

[1] Damian Barr (2025: 87) The Two Roberts, Edinburgh, Canongate

[2] Ibid: 198f.

[3] Ibid: 307

[4] Ibid: 301

[5] Ibid: 298

[6] Ibid: 299 & 1 respectively

[7] Ibid: 80

[8]Extract below is from Ibid: 82

[9] Ibid: 29

[10] Ibid: 132

[11] Ibid: 196

[12] Ibid: 196 (the cock-like cumber is ibid: 215).

[13] Ibid: 197

[14] The excerpt below is from ibid: 194

[15] Ibid: 2

[16] Ibid: 54

[17] Ibid: 107