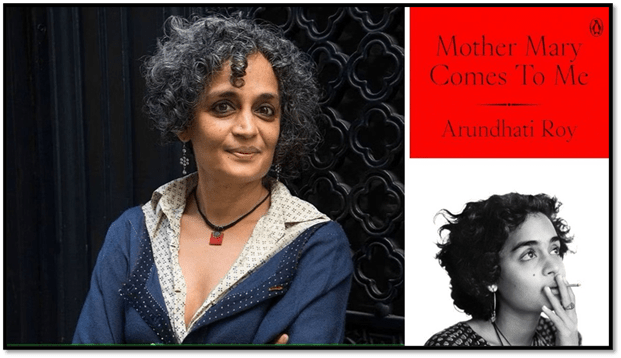

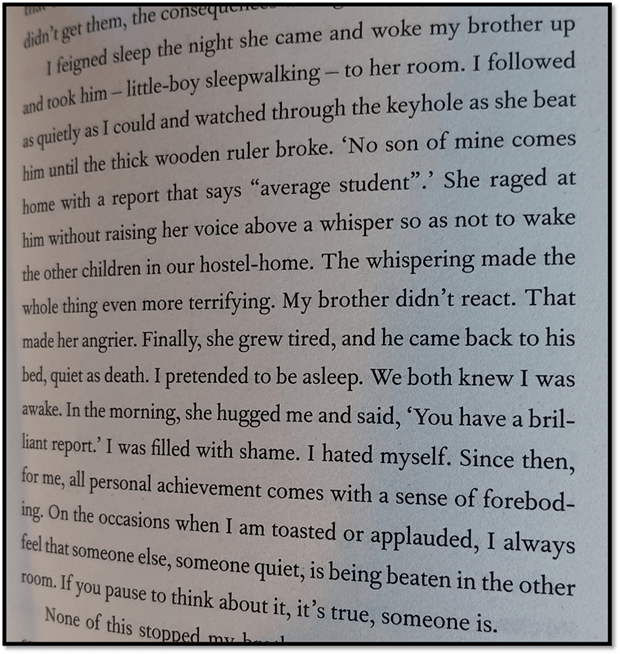

The best piece of advice is to read Arundhati Roy’s ‘Mother Mary Comes To Me‘ as soon as possible. There is an episode in Arundhati Roy’s 2025 memoir Mother Mary Comes To Me in which her brother, having brought home a school report saying he was an ‘average student’, is seen by her taken into their mother, Mary Roy’s bedroom and thereafter watched by her ‘through the keyhole as she beat him until the thick wooden ruler broke’. The morning after Mary hugs her daughter saying she had a ‘brilliant report’. Arundhati remembers that she was ’filled with shame’ and then ‘hated myself’. Afterwards Arundhati reflects: ‘when I am toasted or applauded, I always feel that someone else, someone quiet, is being beaten in the other room. If you pause to think about it, it’s true, someone is’.[1] This episode feels deeply resonant of the scenarios analysed by Sigmund Freud in his essay on the psychopathology of sadism and masochism known in English as A Child is Being Beaten.[2] Whilst Roy certainly does not mirror the examples in Freud nor his analytic conclusions, the concerns about the slippery nature of considerations of sex/gender, power and the nature of the pleasures and pains of achievement and consummation are deeply relevant to this wonderful book about the personal/political/sexed/gendered nature of imaginative work.

Arundhati Roy reveals in a late chapter of her book concerning her visits to her mother, Mary Roy, that she once ‘told me with a laugh, but with unmistakable pride, that people thought she had achieved purushaprapti – the status of a man’.[3] There is a joke here, of course that engenders the laughter and turns the spiritual principle of Hindu Philosophy, in the hands of two non-practising Christian women, into a sublime self-justifying joke. The term purushaprapti is I think derived from Hindu metaphysical philosophy relating to the nature of creation of the universe, and its recreation through time, as a union of spirit (Purusha) and matter (Prakriti) – very baldly oversimplified – into the principles of the union of the masculine and feminine that gives to bold but unruly material action witnessable shape and purpose (masculinises it) that it also connotes. It is all suggestive of the union of the shaping principle of the universe. For two women who are witnesses without the need of male authority of their own focused and directive creation – in law/education and politics/art respectively – gaining the ‘status of a man’ is very much the joke they play on Indian society, and which unites them, despite the antagonism between them as mother and daughter, who would prefer not to be marked out by these familial and domestic secondary roles.

But the joke runs deeper – picking up as it does the transgendered themes of The Ministry of Utmost Happiness (Arundhati’s second and most fantastical novel). It ultimately attempts to analyse why and how Arundhati Roy becomes a shaper and maker – artist-philosopher-powerbroker – as a result not of her mother’s care but of her divine neglect by her mother. Later in my blog I will relate that underlying current of this memoir to the invocation of Freud’s A Child is Being Beaten, but here let’s dwell on the felt strangeness of this book as it tries to reconcile oppression to acts of loving creation and recreation, resistance of power to acceptance of love, the pain of being to the finding pleasure therein. There is no need to invoke Freud. Amit Chaudhuri in his beautiful understated review in The Guardian, expresses this queer ambivalence and ‘freedom’ in Roy’s writing thus, which, as we shall see Roy attributes to her mother being, in Chaudhuri’s words, ‘perpetually at war’ with her’, thus:

This attempt to understand the compulsion to love what seems hostile transform’s Roy’s writing, lending her prose, especially in the first 130 pages or so, an unprecedented freedom.[4]

Of course such paradoxes – loving that which seems determined to destroy you if it can’t shape you in its image u– can be explained in other ways than Freud’s transformation of the issue of power and authority to interchanges of pleasure and pain, sex/gender binaries, liberation and oppressive control and love and hate, into a study of the ontogenesis of the dependency of sadism and masochism on each other, modelled by the ambivalences that mask themselves as parental love but it is difficult to find a more fruitful statement of the fantasy of one’s own narcissistic pleasure being dependent on the sufferings of those less vulnerable than oneself than his otherwise dry essay. I prefer these other ways of finding an explanation but feel drawn to Freud because he puts queer transitional and metamorphic experience at the centre of his understanding of the subject. Here, but more fully in Roy’s exquisite controlled-but-yet-free-prose again is Roy’s version, which makes it clear that her concern is not with ‘the child’ that is being beaten in this ubiquitous fantasy (hopefully less prevalent today than the bourgeois family in Freud’s Europe or Roy’s India in its twentieth-century becoming):

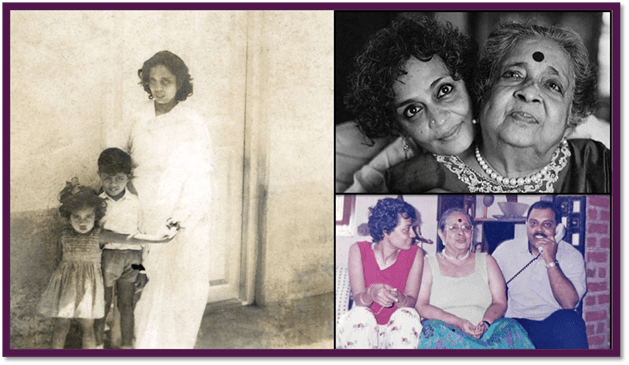

Mother Mary, whether she be the one in the Scriptures and Catholic religious Art or from The Beatles song honoured in the books title, but also often associated with other feminine icons, not least Medea with a ‘wrath against motherhood itself’, and given the multiplicity of the occurrences of her vengeful ‘wrath’ and fury’ the Furies, for her ‘furies’ orchestrates the novel – more effective when vicious in its silence, seeking vengeance for being betrayed by those who do not try hard enough to honour the mother, or can be persuaded they have failed in doing so; ‘her temper, already bad, became irrational and uncontrollable’.[5] And ion demanding allegiance, service must be so total that one becomes the substitute for Mother Mary’s ailing body: ‘I attached myself to her in ways she wasn’t aware of. I became one of her valiant organs, a secret operative, breathing life into her’.[6] And while being imprisoned in her body, Arundhati also is the spirit of attempts to escape that prison – in the twice repeated joke of the ‘escape-goat’ (both the scapegoat of her mother’s deficiencies and the means by which escape is attempted by ‘running’) – forever running (‘my way of exorcising bleakness’).[7] But even escape is a reflection of the mother who when she isn’t Mother Mary, or Mrs Roy, is the arch popular escapologist, Houdini. When Arundhati is running away, she is equally running back in an extended race track to her origins in her mother, who, if she was ‘to shine her light on her students and give them all she had’ meant that ‘we – he and I – had to absorb her darkness’.[8] By ‘he’ Arundhati refers to her brother but is it not equally to the masculine double inhabiting Arundhati as much as it does Mary, trying to shape femininity into patriarchal forms (the even so many inadequate (and some passable) Daddies in the novel) – even in order to fight against patriarchy.

Arundhati with mother, Mary Roy, and in two case LKC as well -at various ages.

We ought to return to the passage above to see how dark it is, how much ‘darkness’ it has absorbed. Mary turns Lalith Kumar Christopher (LKC) Roy, her son, into Freud’s child who ‘is being beaten’ (usually a boy Freud reports from clinical cases and as equally imagined by the women as the men he analysed) as being beaten by his father (who is here a mother). Freud insists in the text A Child Is Being Beaten (download it from this link) that this child is moreover a repressed wishful substitute for the one who witnesses him being beaten. He (although sometimes she) is imagined simultaneously as an object of pity because punished, but also of satisfaction because the punishment is thought to be deserved and therefore also sadistically enjoyed by the witness. On top of this (s)he is also an object of envy – for the masochistic pleasure of pain in being beaten is a substitute for the fear and desire of being taken with pain sexually but with forbidden pleasure (none of which the child understands but knows adults do) by the father. Arundhati’s assumptions about the world – domestic, social and political is that all pleasure that one experiences in oneself, especially following some praiseworthy achievement, is as the cost of the pain to ‘someone else, someone quiet’ being beaten in the other room to a kind of death for LKC returns to bed, ‘quiet as death’. And that ‘someone else’ is also one’s own taciturn shadow self. Casting all this into a family romance drama about the origin of sexual forms and sex/gender modelling shows us that Arundhati wants us to read the account of her political relations to India in similar ways – if not the same – as Freud does.

Arundhati Roy in an interview cited by The New York Times was asked: ‘Why do you think authoritarian leaders go after people like you, people who deal in ideas?’. She answered that such leaders:

are terrified of people who they feel can communicate, not just cerebrally, but emotionally. … they know there are some people who people eventually do listen to. They know who is read. They know who is loved. They also know who is not invested in the things that everyone else is invested in — fame and money and awards. There are a lot of people like that who they know will not bow down. We are just people who look at things and say it how it is’ (my italics). [9]

Speaking directly to interviewer Lulu Garcia-Navarro Roy even amplifies the ‘child is being beaten passage to a political situation not covered by the book, for by then her mother was dead though sh sense that Mary Roy would have sworn allegiance to those suffering in the quiet of the shamed world in Palestine – not Hamas but the victims, who still have resistance in their hearts against oppression, of brutal patriarchal settler-colonialist genocide.

When you get applauded and rewarded and everybody claps and you know that somebody you love and somebody quiet has been beaten — to me that expands far beyond my brother and me. It expands into the country that I live in now or the world. I might be a writer with whatever is conventionally known as success. But the things I write about and the people that I write about are being beaten, even as we speak today. They are being starved in Gaza, they are being broken, they’re being occupied. And so what does it mean when you are applauded, when your heart belongs in the whole world?[10]

Roy says this over and again to interviewers, although not as directly related to my quoted theme paragraph. For instance Soutik Biswas, India Correspondent for the BBC, reports her story and words thus:

Roy once spent a day in jail for contempt of court. She has also faced legal cases, accused of being “anti-national” and “anti-human”. I asked her whether, after decades of writing on big dams, Kashmir, nuclear weapons, caste and Maoist rebels – circling questions of justice – the absence of change ever feels futile, or if persistence itself becomes the point?

“I am a person who lives with defeat. It is not about me, it is about the things I have written about – those have been smashed over many times. Should we shut up because nothing is happening? No. We have to keep doing what we do,” she says.

“We need to win. But even if we don’t, we need to keep it up.”[11]

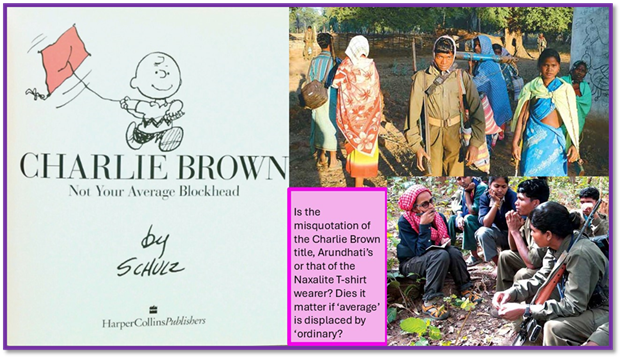

If the struggle seems eternal that is because the vulnerable who resist the taking from them the signal even of any power of independence they might have in the future from the more mighty power structures, institutions and militias of the status quo are like the child who is beaten because he/she/they/it can be whilst the privileged and entitled of the world feel happy to pretend it is not happening. These vulnerable are being treated as ‘children’ in ways that diminish and marginalise them, and ‘beaten’ to prove the point. Those sections of this memoir that deal with the dispossessed of the Narmada Valley Dam Project (and other ‘Big Dam’ projects), the first Gulf War (on ‘Terror’ but in fact war on those whose power must be alienated before it comes to any self-realisation), Kashmiri Muslims under Hindu-Indian Nationalist occupation, and most complex of all the ‘childlike’ resistance movements, the Naxalites. The ‘greeter’ of Roy for the Naxalites when she prepares for writing Walking With Comrades wears a ‘tattered T-shirt’ that says “Charlie Brown, Not Your Ordinary Blockhead”.[12] Very much earlier, and before she had met them, and considering herself and her family ready to be identified by them as the ‘class enemy’, she had summed them up as a movement which ‘ignited the imagination of angry, frustrated students and young people’.[13]

But if the young and unready don’t fight who will or can. You can see in this the same fire that unites all the great novelists inspired by John Berger, and Berger himself, continuing a young rebel up to his 90s, and in this book relating to Arundhati as if she were the child to his Daddy, a Daddy imagined as ‘like an old elephant’ flapping my ears to cool you down’ when she got upset about some political injustice that might stop her writing The Ministry of Utmost Happiness.[14]

But this portrait characterises the ‘gangster’ in the novel who appears in it as Mother Mary, who never said, ‘Let It Be’ and never thought there ‘will be an answer’ unless someone finds one from heroic acts of empathy and co-struggle with the oppressed. No Beatles’ Quietism for either Mary or Arundhati:

Roy participates in a demonstration held by the National Alliance of People’s Movement, in New Delhi in 2006. The demonstration opposed letting agricultural land be used for a car factory. Credit…Manish Swarup/Associated Press. See Lulu Garcia-Navarro (2025) op.cit.

When I find myself in times of trouble, Mother Mary comes to me Speaking words of wisdom, let it be And in my hour of darkness she is standing right in front of me Speaking words of wisdom, let it be Let it be, let it be, let it be, let it be Whisper words of wisdom, let it be And when the broken-hearted people living in the world agree There will be an answer, let it be For though they may be parted, there is still a chance that they will see There will be an answer, let it be

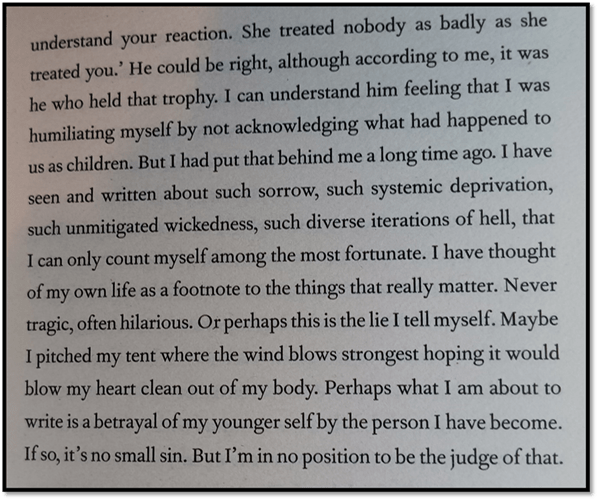

And the reason that there is this paradoxical bond between a mother and daughter who both feel that they have been victimised in their childhoods – by a male or his substitute in a woman with the status of a man – is that they both embrace their being beaten at their most vulnerable in order to understand that other achievements are secondary to the awareness that someone somewhere, who is ‘quiet’ is being beaten more than one could ever have been and that you need to do something about it. This Arundhati says early in the novel as she answers to herself, why she did not feel it necessary to see herself as her mother’s victim but as her queer ally in the analysis and attempted amelioration of ‘systematic deprivation’.[15]

Let’s face it what matters is that her mother made her both an observer of the injustices in human interaction, in the psychological devices we use to ‘escape’ them, ‘flee’ or ‘run’ from them (like the invented ‘escape-goat’ in this memoir) or take unsure ‘refuge’, as the protagonist this memoir’s opening does in a river flowing past a pickle factory that ‘makes up for everything that was missing from my life’ (a refuge recreated in The God of Small Things.[16]

Mother Mary is venerated not only because of her ‘radical kindness, her militant courage’.[17] She is venerated because causing her favoured daughter to fixate, and become ‘victim’ of, attempts to understand the multiplicity of selves underlying her contractions and aggressive use of her power, she provides the base skill of the novel involving the mastery of cognitive and emotional variations. She opened up imagination of multiple character developments because she had not one pathway or road opening out for an ambition but a mixed tangle of such interactive roads and pathways, like those in this memoir. That interaction of tangled routes and paths is a ‘labyrinth (for blogs on the art of the labyrinth follow this link and those embedded in that blog). And the novelist is per se a labyrinth, a metaphor George Eliot would have understood only too well.

The labyrinth though traditionally a trap or a prison is also a means of understanding what puzzles: ‘that gift of darkness’ in order to make that break to existential ‘freedom’.

I learned to keep it close, to map it, to sift through its shades, to stare at it until it gave up its secrets. It turned out to be a route to freedom, too.[18]

Above all that Mary made Arundhati ‘the kind of writer that I am – and then resented it’.[19] That ambivalent experience of the mother as the sole spur to poetic making – the origin of the word poesis is he act of making – is what Arundhati thought, even as a girl, separated her out from the norm of persons whom she named then ‘“MummyDaddy” people’.[20] Daddies matter in the novel mainly because they are interchangeable and often used temporarily to fill a gap. Roy’s biological father, Mickey, Mary calls a ‘Nothing man’ and Arundhati first consciously sees him as like a child to her care henceforth as a kind of inverse mother: ‘He was lying on his stomach with his knees bent, his feet waving at the ceiling. … / .. frail as a small bird, lame and hunched over’.[21] Some Oedipus – another ‘lame’ father – that. The first nominated Daddy is the architect Laurie Baker who also inadvertently and unintentionally finds her a ‘Jesus Christ’ husband and models her first career as an architect, and yet he does not last, his ‘progeny’ truly being the school and school-house which Arundhati inherits (to rebuild herself), but the first of other – not always named but clearly made into father figures. Fathers are merely entitled beings – as Arundhati hints by saying: ‘Had Micky been a woman, would the world have made place for such buoyancy, such beguiling irresponsibility?’[22]

Oedipus, now blind and lame is led away by his daughter, Antigone. The phase of the Oedipus complex Freud never got his sage and revered head around,m any more than he did the puzzle that was Anna Freud.

I think I might end this piece with fathers, for their practical absence (invented only when needed out of their cultural rather than biological significance – is the essence of the feminism Arundhati inherits from Mary, even though Arundhati is kinder to individual men than her mother. I end with them for it takes me back to my insistence that behind this novel lies Freud’s dry study of the ontology and aetiology of conjoint sado-masochism. Academics hate Freud because their vocation causes them to read him too literally – an issue his greatest follower Jacques Lacan takes up by preferring to be merely absorbed into general discourse and not worry too much about being definitively understood. Gret writers do not have this obligation. In my reading of this novel, Arundhati reinvents all of that great essay A Child Is Being Beaten by ignoring any pretence to being a scientific hypothesis that can be supported or otherwise by evidence. In her hands the ubiquity of beaten ‘quiet’ vulnerable others is why pleasure and pain must unite and be the lever for attempted change, that must be attempted even though unlikely to succeed. Indeed what Arundhati learns is in the chapter title, The Exquisite Art of Failure of the chapter I last referred to in summing up the character of Mickey Roy.[23]

Politics is marred too by spoilt fathers, who are nearer to being spoilt babies: Donald Trum and Narendra Modi, though the latter much more outwardly sinister. She summed up their similarities though and differences to Lulu Garcia-Navarro. In part their similarity is that they fear in her, what in them is merely a fictitious authority awarded only patriarchal authority – that if challenged continually, might eventually pass away:

They are terrified of people who they feel can communicate, not just cerebrally, but emotionally. However small they are, and even however little access they have to the mainstream or to the thundering, pulpit-thumping television anchors, they know there are some people who people eventually do listen to. They know who is read. They know who is loved. They also know who is not invested in the things that everyone else is invested in — fame and money and awards. There are a lot of people like that who they know will not bow down. We are just people who look at things and say it how it is. (my italics)

In finding her MummyDaddy in one parent, a mother, Arundhati posed and solved the challenge of all great writing as she also told Lulu Garcia-Navarro.

When you write something like this, you choose what you write and what you won’t write. But I know that this doesn’t work as literature if you’re trying to present some acceptable version of yourself or of her. Then you might as well not do it. But it wasn’t so much of a struggle because what was incredible about her was that there was a part of her that hammered me but then it also created me. There was this public part of her, which was so extraordinary, so I could never settle on what I really thought or felt. The entire range was a challenge to me as a writer: Can I put down this unresolvable character?[24]

This is a memoir that demands to be read but is in fact not classifiable as a memoir but an act of honour to autopoiesis. That is why the apparent humility of the opening pages is neither humility nor about making small and limited claims for her book. For fiction is conjoint with ideology and if we change ideology, believe it or not we change what we see as the world of fact itself. Talking about early childhood memory she says:

I really believed it was fiction. I learned that day that most of us are a living, breathing soup of memory and imagination – and that we may not be the best arbiters of which is which. So read this boo as you would a novel. It makes no larger claim.

But let’s face it, she only says this because that claim about what novels are is the largest claim ever – one potentiated to re-frame memory and imagination to new truth. So take my advice. You just have to read this book. It’s important – but its great fun too.

All the best and with love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Arundhati Roy (2025: 43) Mother Mary Comes To Me London, Hamish Hamilton / Penguin

[2] Sigmund Freud trans. James Strachey (1981, originally published 1919) A Child is Being Beaten (A Contribution to the Study of the Origin of Sexual Perversions) in Angela Richards (ed.) On Psychopathology: Inhibitions, Symptoms and Anxiety and Other Works: Volume 10 Pelican Freud Library 159 – 194.:

[3] Arundhati Roy (2025) op.cit: 43

[4] Amit Chaudhuri (2025: 50) ‘A strange inheritance’ in The Guardian (Supplement) Sat. 6th September 2025: 50.

[5] Arundhati Roy (2025) op.cit: 22

[6] Ibid: 34

[7] Ibid: 42 See the escape goat ibid: 20, 145

[8] Ibid: 53

[9] Lulu Garcia-Navarro (2025) ‘“The interview”’: Arundhati Roy on How to Survive in A Culture of Fear’ in The New York Times (Aug. 30, 2025) Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/08/30/magazine/arundhati-roy-modi-trump-interview.html

[10] ibid

[11] Soutik Biswas, India Correspondent at the BBC (2025) ‘“My mother was my shelter and storm”: Arundhati Roy on her fierce new memoir’ BBC (Online) [4 September 2025] Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c4gzdnp43l8o

[12] Arundhati Roy (2025) op.cit: 332

[13] Ibid: 47

[14] Ibid: 328

[15] The photographed except below is from ibid: 3.

[16] Ibid: 20

[17] Ibid: 5

[18] Ibid: 53

[19] Ibid (it is quoted in every review of the book but for the life of me I can no longer find the page reference – that’s life!).

[20] Ibid; 42

[21] Ibid: 163f.

[22] Ibid: 174

[23] Ibid: 174ff.

[24] Lulu Garcia-Navarro, op.cit.