What does your ideal home look like?

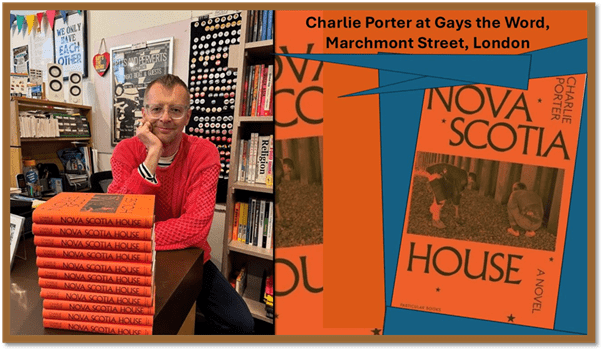

What does your ideal home look like? Of course, it shall look like number 1, Nova Scotia House. This is a blog on Charlie Porter’s 2025 novel, ‘Nova Scotia House’, and the impossible queer magical thinking it makes possible.

The prompt question here is a kind of trick! The question underlying the one ostensibly asked is to describe the house of your imagined aspirations – that which matches the person you would like to see yourself as being currently or becoming in the future. It will describe aspirations as to the ideal relationship the house will make itself the home of and usually too aspirations of status, income (preferably perhaps not too visibly earned by anything like hard labour) or achievement.

Moreover, in doing so, the more to impress its readers, it will both follow and further some norm of what our culture determines as the signs of personal and / or familial success looks, feels like. Of course, it might invite fantasy, sometimes of the kind that even further promote norms by showing the bases of the culture’s dream of home, as Robinson Crusoe’s habitation does as it grows ever more to resemble the well defended house of an overlord of all available space and power in its vicinity. Though the desert island fantasies we name Robinsades suggest the spartan existence of the survivor of shipwreck, they also promoted the image of bourgeois independence and self-mastery based on the selfish appropriation of resources from nature and such society as existed, including even in Robinson Crusoe, his own colonial rights over a Man Friday he pretends to befriend whilst he actually subjugates him to a slavish role.

Nova Scotia House, the debut novel of the queer fashion writer, Charlie Porter is named after a house of multiple occupancy inhabited by its protagonist and narrator Johnny Grant, who lives in one section in that house (no. 1) the home once occupied by the 45 year old (when they met) man that he loved, Jerry, after the latter died of Acquired Immune deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) complications in the 1990s, some months before the discovery of the wonderfully effective anti-retroviral drugs that have robbed AIDS of the status of being the inevitable conclusion of HIV infection. But home-making is not only seen in this instance of one home made from one house in the novel though I choose it as a kind of realised emblem of the way houses are made into homes for living in by individuals or groups (from dyads upwards) – there are homes associated with many characters – the final one we see being a seaside farm house that will house a kind of working commune – but that include those of Johnny’s other sexual partners and friends, notably Gareth (whose London home sells for a fortune) but also the ‘warehouses’ turned into ‘squats’, as they were called then but not in this novel, where people redrew the norms of the family, neighbourhood, community and the meaning, form and potential for novelty in the relationships within them.

One major background character who appears at significant transitions in Johnny’s life moreover is an architect, Fiona. Though Fiona teaches the building of homes has never designed nor built one. Fiona has her reasons. She says that at its culmination in one year she went to 14 funerals of friends who died of AIDS: AIDS has destroyed for her of continuing to live a life as she had done and instead ‘pushed me inward’ and ‘hardened’ her. Now a kind of hard shell conceals almost existential questions that lack any clear direction about the feasibility of living a life and imagining the conditions that enable life.

How can we live? What conditions do we need to be able to live? That was my path. Theory not practice. … And so here I am, an architect who has never built. My interventions have been slight, the interiors of places, like this place. …

Asked by Johhny is she would like to be build that which she tries to design and draw, she sums up the effect of having no answers to the questions she asks inside herself as:

…the impossibility of building. Building well and with purpose and without compromise.

Though she points to the kind of building proffered by architects who do not address the question of living – providing perhaps only ‘a cube dumped on the skyline, an aggressive block of weight’.[1]

The metaphors used by Fiona are ones that are used by Johnny too though sometimes they are not merely metaphorical but almost realised as elements of a real city landscape, such as paths and roads that oft lead nowhere, or to or through a waste, dank or barren land, where building responds only to supply and demand not questions of how to live an authentic life:

It was a dank land, I did not understand it, could not comprehend its roads, its paths, its meaning, where it went, it is still that way to me now, I do not understand it, the city does not want me to understand it, that is not its purpose, the city is there to make money for others, …[2]

The repetition of ‘I do not understand it’, is a sign of the directionless of the land through which we pass in the novel that meet no expressible need. Vast towers of faceless building are made to maximise profit on land that was once unwanted and are not just a ‘block of weight’ but block out living light, as the building does that, in cutting out light to the produce garden of 1, Nova Scotia House, leads to Johnny having a leave that place and space wherein he might rather have stayed had it had light and comprehensible use for maintain life streaming into it, making a garden that grows the things that facilitate human growth. Likewise, actions are often expressed as ‘possible’ or ‘impossible’: the conditions of their possibility being somewhat like life a hard question to crack in the face of the devastating waste and decay created by AIDs and a kind of deadly if ordered and organised paradigm of normal life required by capitalism, wherein the governance of human society was happy to fail when that its aim might have been ‘a society that helped other, that cared’.[3]

At the core and heart of the novel is Jerry who lives and dies in it attempting to revive a mode of life associated with the world of the 1970s, where buildings like warehouses might be commandeered to act as a means other than as storing life, but rather animating it, letting it grow by relaxing human over-regulation of it. His view of life is that it is full of traps, nets and prisons and ideals that stultify rather than free and from which most of his action was, and might have continued to be without AIDS, ‘escape’ from such regulation and where worlds where not ‘given’ together with limiting conditions but created anew as a space for self-expression and which speak of freedom not bondage – in relationship, stultifying formal behaviour or ‘buildings’ and grids of ‘streets’. Later this will come to be called ‘Queer Magic’, but it has not got the title when we see it early on as a description of the music of ‘queer black geniuses’:[4]

If this was the days when the phrase the ‘personal is political’ meant anything this was the most pertinent, if almost anarchistic, expression of that phrase, and it speaks to me in ways it only can at second hand to Johnny who was not alive in those days as Jerry, and Gareth were. A poignant moment in the novel is exactly that where Gareth tells the young man Johnny that, despite the love felt both ways between he and Jerry, Jerry would not have ‘hung around’ to have lived as a couple with Johnny had he not been dying of AIDS, for true life is growth without over-regulation, even that scaffold built by mutual love.[5]

Queer Magic (pronounced by Gareth as ‘Qu-ee-er mmm—ag-ic’) is described as if it were the product of life lived as art, as a kind of magical thinking that denies the realities of time, aging, disease and death, once it is expressed:[6]

Though he and many others die (consumed as society under its current norms consumes everything), Jerry says, on his death bed that: ‘Our Queer Magic is alive queer magic will always be alive’ (using that characteristic piling on of phrases with the same grammatical subject by different tenses of the verb ‘to be’ which makes his point about time).[7]

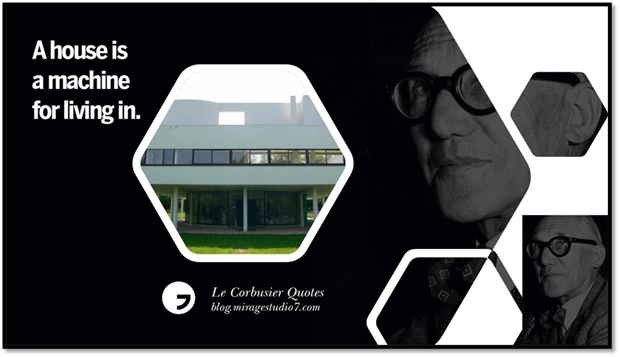

And this is all about ‘ideal homes’ that must not be ideal – that is, the expression of that which we are entrained to see as ideal by consumer capitalism and advertising – nor, in the phrase of the most famous architect of the period, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, better known as Le Corbusier: ‘machines for living’;

For mechanisation of life is the enemy – a kind of dynamism of regulated function as in the phrase above about becoming a ‘cog in the machine’. Moreover, I suspect Porter thinks this is true of novels too and is probably why a keen observer like Olivia Laing sees this novel as doing something new by reviving cultures she herself has done much to revive. In an interview with Anna Cafolla in Vogue, Porter says:

Fiction writing, for me, is … about letting people live. It’s like The Sims: I build the house, put people in them, and see what they do there. I know to some extent what’s going to happen, but how they spend their time with each other, how they are, happens during the writing. My hope is that the reader can feel that—what’s happening on the page is just happening. A lot of writers work with storyboards but, to me, that could become very stilted. They’re not alive. I let them walk around, I let them go to a party, see what happens. It’s an attempt to mimic an experience of living which doesn’t believe in predestination.[8]

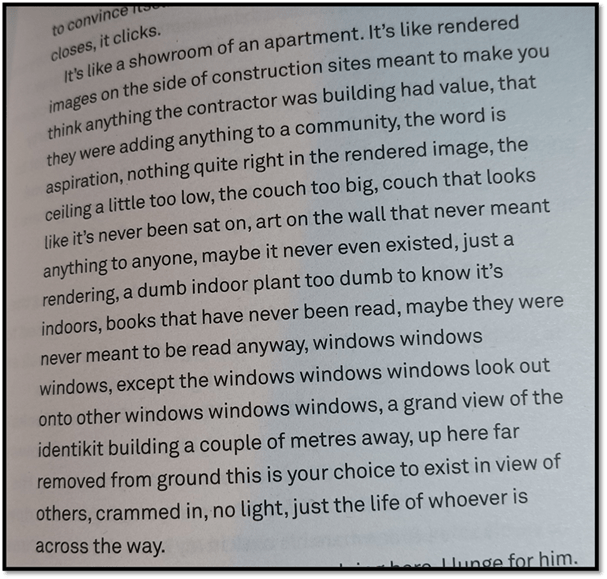

There is no accident involved in Porter saying he made the novel by building ‘a house’: an impossible magical house where the dead continue through queer magic and lives are not regulated by a predetermined script or cognitive schemata. In order to show this, he creates some characters who are all either over-regulated or ‘clean’ (the word used by some creepy gay men in this novel to say they are not HIV infected (although the word ‘infected’ is hardly an improvement. These are men who hate dirt or ‘mess’, whilst Jerry revels in it, as Johnny learns to do, wiping his semen dripping anus, on the sofa of a man who has had sex with him and who before sex, the first time not this last and second time, tells him not to ‘mess the couch’.[9] This man’s (whose name is forgotten by Johnny – it’s ‘Craig’) life is like the stuff of modern post Corbusier architecture , but now – in an age of reinforced concrete – with so many window panes aping its shaping (in the manner of Mies van der Rohe), his ‘apartment’ the ‘ideal home’ this blog is meant to be about:

And Jerry had theorized his escape into homeless wandering because of his upbringing in the post-war times of the modest but nevertheless ‘ideal’ home, where the nuclear family, deemed the best response to modern living by post-war governments, modelled the Heteronormative value system exactly. These ‘dark times’ said Jerry meant he and his generation grew up in ‘mean homes, and these homes had been meant for mean lives’. (where mean stretches to speak of post war austerity. Everything aped the patriarchally drawn up roles meant to lived as life models in it and to escape meant distaste by queer thinkers – thinkers who rejected the norms – of ‘a miserable two up two down with its toxic assumptions of how life should be lived and who had control’. Moving into the ‘warehouses’ was – forcing in the architect’s and sketcher’s imagery a chance to ‘redraw the way we lived’.[10] When they took a house, they made it ‘home’ by making it a place with fewer boundaries between inside and outside (especially the garden where you ‘grow to live’) but could not defeat the charters streets of a city not theirs. From Hamstead Heath Johnny ‘couldn’t see our home, the whole city was meant to be our home. It was not our home’.[11] Yet the patchwork refuge that number 1, Nova Scotia House becomes to Johnny as he joins Jerry there in the latter’s home is a place where life may be defined by the austerity of its contents and planning (it’s ‘open plan’) is meant not to be ‘heavy’, like the heavy architecture we saw earlier but light in terms of its relative gravity effect and its access to the vision-enabling light around it. Kitchen, lounge and garden are one: ‘It is all the same and one is the other’.[12] Can I find in this my ideal home, although it is so unlike how I live.

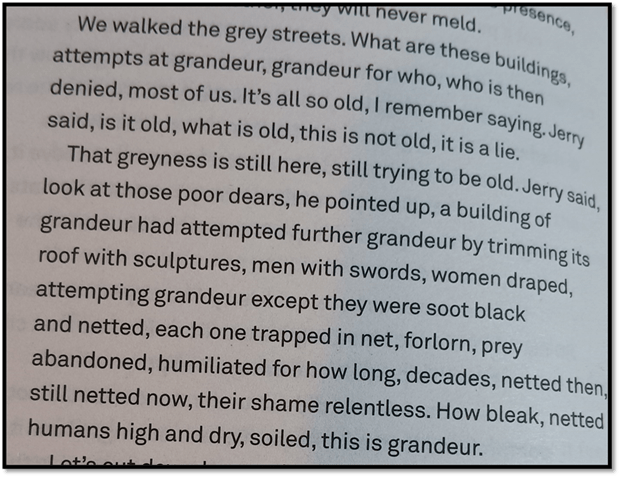

Contrasting architect aims at grandeur, aping old traditions that belong to the few not the many and achieves entrapment: ‘soot black and netted, each one trapped in net, prey, abandoned’.[13]

Of course magic is an impossibility but this novel continually plays with the possibility that might derive from ‘impossibility’, even what Fiona calls the ‘impossibility of building’ in the present age. In a life ‘lived without predestination’ – without a script provided either by God or social norms, relationships are perhaps the largest of the possible impossibilities we encounter, especially when they entail love. Lives lived without scripts draw up the open plans for homes that are a possible impossibility. I think Porter takes this idea a long way, and I still do not understand quite how he uses it to describe the mix of performance and authenticity, the fake with the real and the fact that a relationship becomes possible in queer lives that ought perhaps be impossible. I am thinking especially of the Canadia character, Derek, who lives in Novia Scotia proper when Johnny accepts Gareth paying for him to take a holiday there after Jerry’s death.

He meets Derek in the act of playing a skeletal death role in a ‘Festival of the Dead’: ‘Was this a joke I had come to escape death I had landed among the dead’. When Derek introduces himself from under his skeleton costume Johnny ‘shook his hand his handshake was impossible’. Impossible because skeletons do not usually shake hands – they have none, only an underlying structure, or ‘impossible’ for another unspoken reason, like the fact that afterwards it is clear that ‘Derek knew everybody, everybody was impossible’ (skeletons don’t have bodies) and ‘was talking to everyone he introduced me to everyone it was impossible’ such that Johhny ‘was at a sea of impossibility’. That event passed, Johnny tells us of Derek: ‘His impossibility in daylight was more possible, …’.[14] How are we to understand this loose grammatically and semantically disordered prose? It is impossible because it is possible, and vice-versa, just like the relationships queer people make, out of nothing as it were.

And that is an element of queer magic and queer magical thinking that animates this novel and builds its impossible homes like number 1, Nova Scotia House. Again in his interview in Vogue, Porter says that the point of this book is that it must resurrect the dead from, as it were, nothing – an absence of sources (unlike his book on the Bloomsbury Group).

The reason I wrote the book was because I wanted to tell the stories of queer, countercultural lives that aren’t otherwise documented. My nonfiction relies on letters, diaries, archives. Queer lives have so few primary sources, particularly in the 20th century, before and during the AIDS crisis. If I wrote this as nonfiction, there would be gap after gap, or there would be a homophobic New York Times report to point to. In the ’80s, the media would describe the partners of people who had died of AIDS-related causes as “longtime companions.” It’s also often the case that narratives around AIDS become very elegiacal. But fiction was the only way for me to get close to what I wanted to say about these people and their experience of living countercultural lives. The purpose is to reconnect with experimental living from before the AIDS crisis. I could do that through language, making it as intimate as possible. I guess what I’m doing is inventing primary sources in the text.

The point of it all – is it possible to write in situations where written records were impossible, or virtually so? Can we ‘invent’ primary sources that have the possibility of life and can manifest, as only living beings can, the potentials of counter-cultural living – living for which there no exact prior models? The counter-cultural of a past age has to become the counterfactual of a present that has wiped out pre-AIDS counter-cultural modes of living and their motives and made that possible alternative present impossible. How can what is lost be found? Perhaps only the imagination peculiarly let loose in innovative fictive modes, as he again says in the interview:

There is an entire ecosystem lost that we can’t begin to fathom, so what we can do now is imagine a parallel universe where it all would have happened. We can consider how we can encourage alternative ways of living, thinking, and making, rather than acquiescing to what’s become the norm when the norm has happened against us, and the norm is not good enough.[15]

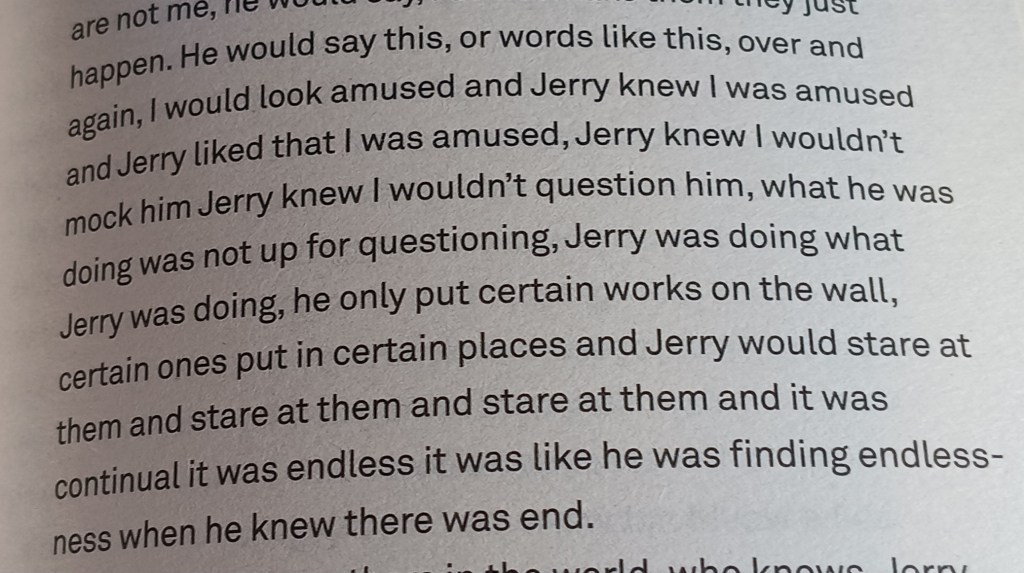

Perhaps the tragedy of this book is that it can only imagine the present that might have been had AIDS not killed off the witnesses of the counterculture in the role of art – art that is a continuing ongoing process of making and not end-stopped at the making of a product. This seems to be the reason Jerry is a painter in this novel – a painter careless of selling his art or even of finishing it, even his reinterpretations of it are continuations of the artistic process as if it were unending. Porter mimes this by expressing it as a seemingly endless sentence that resists the full stop it must eventually have as he enacts the process of ‘finding endlessness when he knew there was an end.’ Never has a FULL STOP been so vocal as here:[16]

So much then for my ‘ideal home’. It is as imagined as the ideal homes of consumer capitalism but it posits ways of doing ‘home’ that have no exact script, even in the countercultural past – but the process of imaging is endless and cannot be just purchased and consumed.

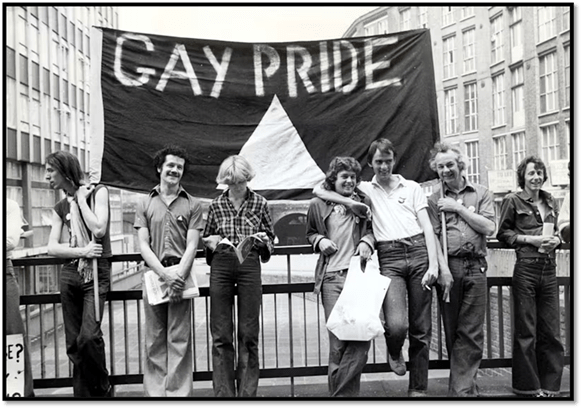

That’s my husband on the right – outside the Old Bailey whilst Gay News was tried for blasphemy.

Bye for now

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Charlie Porter (2025: 207) Nova Scotia House London, Particular Books / Penguin

[2] Ibid: 15

[3] Ibid: 9

[4] Ibid: 35

[5] Ibid: 208

[6] Ibid: 58

[7] Ibid: 158

[8] Cited in Anna Cafolla & Charlie Porter (2025) ‘Interview: Charlie Porter’s Debut Novel Reclaims What Queer Life Lost to the AIDS Crisis’ in Vogue (March 21, 2025) available at: https://www.vogue.com/article/charlie-porter-nova-scotia-house-interview

[9] Charlie Porter, op.cit: 42

[10] Ibid: 76f.

[11] Ibid: 88

[12] Ibid: 1

[13] Ibid: 16

[14] Ibid: 174 – 178.

[15] Cited in Anna Cafolla & Charlie Porter (2025) ‘Charlie Porter’s Debut Novel Reclaims What Queer Life Lost to the AIDS Crisis’ in Vogue (March 21, 2025) available at: https://www.vogue.com/article/charlie-porter-nova-scotia-house-interview

[16] Porter op.cit: 135

One thought on “What does your ideal home look like? Of course, it shall look like number 1, Nova Scotia House. This is a blog on Charlie Porter’s 2025 novel, ‘Nova Scotia House’, and the impossible queer magical thinking it makes possible.”