In metafiction, the narrator may make ad-hoc decisions about the nature of the fiction and adopt, if not fully implement, them in the very moment of narrating that fiction, as in the end of Jonathan Buckley’s 2025 novel, One Boat where it appears that the narrator decides (on authoritative masculine persuasion) that her book is a submerged ‘quest’ narrative. But just because she comes to that decision does not mean that the reader may not feel mislead into a reduction of the narrative’s potentialities towards alternate forms or that the novel actually changes in any way for the reader. This is a blog on the rich novel that is Jonathan Buckley (2025) One Boat, London, Fitzcarraldo Editions.

In metafiction, the narrator may make ad-hoc decisions about the nature of the fiction being consciously adopted in the very moment of narrating that fiction, as in the end of Jonathan Buckley’s 2025 novel, One Boat where it appears that the narrator decides on authoritative masculine persuasion that her book is a submerged ‘quest’ narrative. For instance, at the literal end of the narratives held back from progression by that ending, the unnamed female narrator chooses, on the advice of a more assured novelist (named Patrick and with a longlisted prize novel) to use her narrative to model a quest with a teleologically (‘end’-focused – see my blog on this) and ethically designed narrative process. Such narratives seeks to keep moving towards in a specifiable direction towards some goal or moral purpose (such as the nature of true judgements and objects in life). However, in telling Patrick that he is ‘right’, she abruptly stops all narrative momentum (or ‘moving on’) altogether at a final full stop. Just because she comes to that decision does not mean that the reader may not feel mislead into a reduction of the narrative’s potentialities towards alternate forms or that the novel actually changes in any way for the reader.

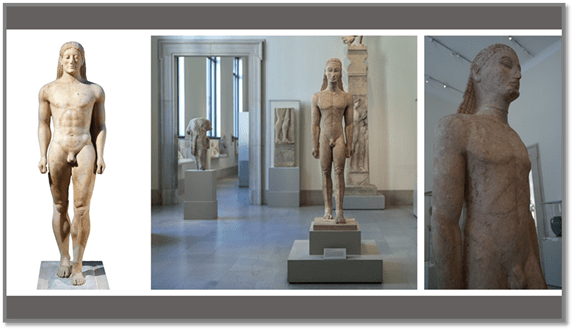

Moreover, such a reinterpretation of what we and Patrick have already read must (in, perhaps the write up of the narrator’s notes that is the current novel) , he says, sacrifice some of its currently narrated elements, especially the narrator’s connection with the ‘hot body’ of the character, Niko, at a point in the middle of all of the collected stories we read, and ‘spin some tighter stories’ with a defined ‘narrative torque’ around the hallowed ‘theme of the father’, currently ‘semi-submerged’ in the text (he says). As always and with other men in the novel, like Petros, for instance (or Petros / Stephen if we decide these are one as Patrick does), she gives way to male authority immediately, saying that: ‘Niko is a minor character in the theatre of my memory’.[1] But just because she comes to that decision does not mean that the reader may not feel mislead into a reduction of the narrative’s potentialities towards alternate forms: such as that she muses upon after four nights of sex with Niko: ‘Begin and end with the beauty of Niko’.[2] For the beauty of the ‘kouros’ may be an end in itself, requiring no justification and self-completing without extension as a necessary and sufficient example of the love of a generalised humankind.

There is no doubt that the story of the narrator’s four-night stand with the man in the novel called Niko is extremely charged though not with anything like an engagement with anything below the surface of Niko, who is a man with definite shallows. The narrator revels in the fact that Niko is unable to appreciate European culture as she does, such as that represented in his ‘sampling Bach, a prelude and a fugue’ (the stuff of how the cognitive and affective configuration of time manifests as musical form), because:

Some distance was maintained. The possibility of deeper attachment was reduced. An encounter – several encounters – with the body of an almost stranger: that sufficed.

I ought to say that though I think I know what she means, I doubt whether such encounters, unrepeated, suffice for long except where they are abstracted and mentalised (witness a novel like John Rechy’s Numbers). Niko is not just a man to her but rather an ‘image’ of the embodied male – ‘the image of the kouros Niko on the edge of the bed’. [3] The Kouros is a beautiful ideal of archaic Greek culture – the unindividuated male religious principle that may have originated in Egypt but stood for beauty as a self-sufficient principle of an almost religious awe and/or supplication. Of course, it may stop short of awe and rest on the belief that Niko is just a ‘top-grade young man’, once one had ‘had’ him for oneself and Patrick may be correct that Niko bears little scrutiny or narrative weight, but he can’t just be eradicated as Patrick wants just as ‘dreams’ in this novel cannot be eradicated because their narrative has no uni-directional impetus or unitary meaning. Patrick may insist that images like that of Niko are ‘like the contents of the kitchen bin, the rubbish might tell you something about the person that created it, but not a great deal, and certainly nothing crucial’. To this the narrator provides a counter-quotation: ‘It is in sleep that the soul most shows its divinity’.[4]

But the issue with Niko is that, reduced to his body alone, his image bears far less, if any, real continuity between the two instances on which we, with the narrator, meet him. What constitutes ‘him’ is less a collaboration between what he seems to the senses and the construction of him in the mind of someone telling those parts of his story that we see in this novel. Like Petros, we see him twice – on the narrator’s first visit to the Peloponnese coastal town in which he lives and on the second, but unlike Petros, whom I will touch on later, he does not appear as a blend and co-appearance of both of the Petros characters seen on each visit, but as something totally depleted. It is a sure sign that, on her first visit, Niko was constituted entirely by her desire and its creative potential to imagine the persisting kouros in him. For in the second visit, he is there no more:

The face and form were very pleasing, very, but the sight of him was less powerful than before. All desire had been expended, it seemed. A heaviness, I noted later. A heaviness of the gaze as much as of the body. And a heaviness in myself.

“You look the same,” he told me.

“Not true. But I thank you for the lie.”

“It is true,” he delicately insisted.

Life must have become better for him in other ways too, I said. The reference was not immediately understood. …[5]

This brilliant novelistic dialogue works entirely by speaking through its gaps in plain speaking, just as do the exchange of pleasantries a boy one’s ‘look’ being the same. Consider again that word ‘look’ in its dual role as a name for the gaze at an object and for its generalised appearance. It is all worked to a maximum in that phrase, so good, the narrator thinks, she notes it in her notebook: ‘a heaviness’. The pictures above are irrelevant except for their realisation of male ‘heaviness’ in a range of manners that might be applied to a middle-aged Greek male with a classic ‘good look’. There is almost no need for the phrase: ‘And in myself too’. For I think this prose invites you to see the source of the looks of Niko on the second visit as mainly changed by the ‘heaviness’ in the narrator’s ‘gaze’ or manner of looking at him – though it also implies that heavy browed framing of the stereotypical Greek male face and the heft of an older body – an amalgam of muscle or other timely deposits. That Niko takes time to understand what the narrator means by saying, presumably in indirect speech of uncertain tone for it is not recorded here as other statements are directly (in speech marks) : ‘Life must have become better for him in other ways too, I said’. That the ‘reference was not immediately understood’ may be because it implies a critique – that he looks too solid, perhaps too ‘heavy’.

And the early kouros was not HEAVY. He is constituted in part in the light of a younger woman’s desire. That’s because, perhaps, there is something less Christian but more divine in the image of the desire of the kouros (usually of a man for a younger one) than in the examinations of teleological moral principles in the Petros / Stephen story (if indeed they are the same story) about crime, punishment, and, retributive and redemptive (or restorative) justice, which might connect the narrative of Stephen, a father’s revenge for the loss of his daughter and grandson and the fall of Petros into a hole. The return from which fall into a mechanic’s hole for working on car engines from beneath changes Petros forever into some kind of symbolist mechanic-poet, looking for meaning in what he sees in front of him.

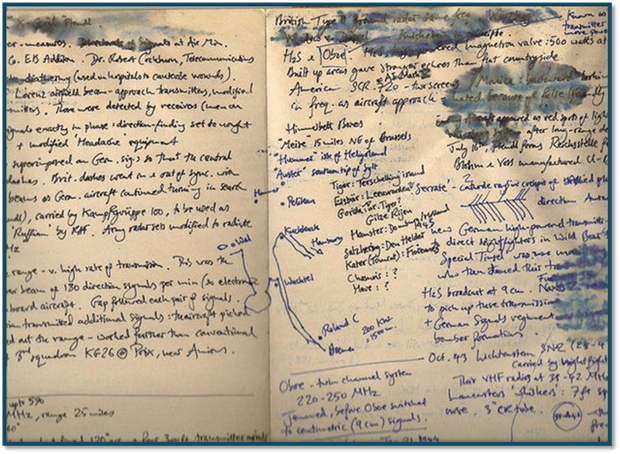

However, there is another way of contrasting the objects of narrative in One Boat. There is a kind of narrative that is not only always ‘moving forward’ but is not teleological at all – it pursues no end or purpose but is continually evoking a world wherein: ‘Everything is becoming – nothing rests’. In such narratives there is no separation of narration, narrative, setting and character where ‘the elements of the scene lost their separation’, more to do with a fluid world where signification is in the totality of experience not its details;

All categories and names were lost in the totality of it, dissolved in light. This was how the episode achieved its climax, in an overwhelming acceptance. An Amen of sorts. This is what I wrote. ‘Ataraxia’ is a word I might have used, had it been at my disposal then’.[6]

Wikipedia usefully defines ataraxia thus:

In Ancient Greek philosophy, ataraxia (Greek: ἀταραξία, from ἀ- indicating negation or absence and ταρασσ- tarass- ‘to disturb, trouble’ with the abstract noun suffix -ία), generally translated as ‘unperturbedness’, ‘imperturbability’, ‘equanimity‘, or ‘tranquility’,[1] is a lucid state of robust equanimity characterized by ongoing freedom from distress and worry. In non-philosophical usage, ataraxia was the ideal mental state for soldiers entering battle.[2]

The achievement of such stasis whilst in change can be applied to the suspension of the errors of dogmas which lead to simplistic judgements and moral decisions, or the achievement of a relationship in principle with time and continual motion in space as principles outside just the present moment (‘eterne in mutabilitie’ in Spenser’s formulation in Canto VII of The Faerie Queene) or just acceptance of life’s vicissitudes. The kouros is one such principle – for it a generalised experience outside of time and separation and the effects of heaviness in ageing, but so are the ideals that the narrator thrusts on John to appease his lust for revenge. However, it matches too the way this narrative sometimes seeks to weld all scenes and episodes in life into generalised versions of themselves. It happens as a result of the duality of the two trips the narrator makes to the Greek town where it is set at the death of her father at her first visit, her mother, on the second visit. They strain towards difference (as Petros’s dogs Sander and Kal do) only sometimes to feel like generic types of each other – as likewise the returned characters. Just as she leaves the town, the narrator sees that:

Everywhere I looked, the daily script was being enacted. The actors may change but the actions do not – selecting from a menu of speech acts, I wrote, plus the line about mild melancholy. But the melancholy had already been dissolved or displaced by the light, the warmth of the air, the activity of the square, the attractiveness of Xanthe. I began to transcribe the material of the scene: ….[7]

Those terms are from the jargon of socio-cognitive psychology, where scripts are schematic of generalised interactions described by theatrical metaphors that guide human life and the various repertoire of limited ‘speech acts’ therein available. Amongst these ‘speech acts’, the mind can ‘slip into another scene, a generic scene rather than one particular moment’, which psychologists describe as the characteristic of episodic memory, where events are categorised into schematic scripts, leading to memorial confusions in terms of memories located in specific times and places, but also to a sense of predictability and déjà vu.[8] Yet these terms are also complicated by the representation by the narrator as the scribe of what she sees and hears and perhaps not only a scribe but a translator who reinvents a scene in her own terms, such that the source of the melancholy and its wane are unclear – they are attributed to the scene but they also arise, we are told, from the translator of the scene and integrate therewith.

Episodic memory both enables us to deal with sequences of time in memory and also, perhaps, make those dealings unreliable, and in this case make our narrator a typically unreliable one. And this is characteristic of the narrator’s narration – yearning sometimes for the specific but even more generally to an acceptance of the generic and generalised in human life. It is not unlike the other dialectical tension in these narrative between ‘moving on’ and ‘staying ‘ where you are.

A Peloponnese fishing town

And this contrast can also distinguish character, either as, like those, according to Petros, in The Iliad and The Odyssey. These keep moving through their stories because they are ‘wholly of this earth’ with:

no secret self, no hidden motives – they know what they are, and they do the things they do not in the hope of eternal reward, nor even of happiness, but for the sake of fame and reputation.[9]

They act in order to have stories told about their action (fame and reputation or more strictly the Greek term Kleos – κλέος), none of which they wish or are capable of inventing themselves.

Whether Petros is of this nature as he claims is a ‘problem’ in this novel. The alternative is for character to lie underneath such apparent plain readability and visibility and be buried or submerged under the surface of earth or sea (in tombs or labyrinthine architectures) – places where the traces of ancient Greek Gods are nevertheless sought in this novel. The narrator can see herself (though binary terminology can confuse here as she tells us)[10] not as a whole unified personality but as the image of that and the ‘occupant of the inner vault’ within that apparent person, which may be multiple in its nature, like –

… a container, a tank, a person-shaped receptacle full of all kinds of organisms, shoals of them, swilling around incessantly.

And if the ‘true self’ is one contained inside something, what is that which looks into the container and scrutinizes that inner self? Is that self too, or a part of self, and if it is does not it have to be scrutinized too, and if so ’where do we find’, in infinite extension ‘the scrutinizer of the scrutinizer of the scrutinizer’. Nothing is constant in such narratives but some sameness recurs, for the shoals are always moving’. No wonder then that Petros says, as many readers will: “You lost me two sentences back”. These deep subjectivities are, Petros says, using the narrator’s metaphors ironically, are: ‘Rooms full of mirrors and aquariums full of whatevers are neither here nor there. That way lies madness’.[11] There is enough continuity between the human variance internal to each individual or memory of them he says to determine that the identity of persons is itself continuous.

Yet the narrator of these stories is never entirely convinced that her characters are solid and embodied and not vacuous and invented entirely from scraps of detail in the outside world. The book uses italics a lot to indicate the way the persons, and what they do and say, she meets are transformed into words in her notebook or some other writing medium, such as a ‘phone’ text, but it is never clear that she is not inventing them as she records them at such a remove, just as she does so brilliantly in recording her ‘conversation’ with Petros’ first dog Sander (himself based on Alexander the Great: ‘Defender of men’).[12] The dog is recorded as having a ‘look that seemed meaningful – a questioning, marvelling look’.[13]

But the point is made more obviously in the omnipresence of books themselves in which text has varying authority with readers – a notebook primarily for a novelist’s note-taking, but also both Homer poems (one for each visit), Petros’s book of poetry, and dictionaries. On arriving in the Greek town’s hotel the narrator seeks to sit , observe and note – the notes appearing in the text as italics, but often interpreting or re-interpreting the events, perhaps even inventing them anew, and perhaps even omitting events, turning physical scenes into events in language alone. There is a fascinating scene at the beginning in which she meets John, a man we will learn with a moral dilemma, who has, when she sees him ‘no map or guidebook’, roles the narrator relishes taking upon herself. Yet when she observed him, she says nothing meaningful of his independent responses to her, glossing it with: ‘There was nothing to note in his response’ (my italics)[14]. From then on we are advised to notice what the narrator finds contemporaneously noteworthy – that which goes in her notebook – for future elaboration and interpretation. It suggests a fundamentally unreliable method of interpreting the world at various removes from experience, but also one which has its uses in melding the teller with their tale.

Even this novel’s book-title itself is transformed into a multiple signifier, including the non-working of its intended signification. Her own style of interpreting becomes itself a thing interpreted, merging into the ‘single boat’ she observes to become a ‘ruby on the flat black water’.[15] And this single boat is perhaps the ‘one boat’ of the title, which may or may not be the same one as at least one of those captured in Petros’ poems where, in one, there is a black boat and a red boat (the latter ruby perhaps) as described by Irina, or more possibly that we read in the final chapter, which may be the same poem for Irina cites from memory and a lack of belief in these poems:

The bay

Lid of black cloud

In one place cracked

Below, in light

One boat

Glory [16]:

To end with Kleos (Glory) is a point in itself, in a man so versed in Homer. Nevertheless, chiefly this shows that we never know from what position in time and space objects or events on One Boat are described – in mental space contemporaneously, or in the notebook or in the more finished prose to be concocted later. Indeed to point the irony of this, the narrator plays games with people as to whether she is ‘a writer’ or not, as she clearly is in the final chapter, sometimes appearing as a lawyer (and sometimes in criminal and sometimes in less stimulating contract cases) but with an interest in jurisprudence – the philosophy of the law, or a therapeutic counsellor with specific knowledge of the stages of grief as enunciated by Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in her book On Death and Dying, or sometimes all of these. And there is, of course, a difference between what the narrator appears to be to others as they reveal their impressions and / or to us as readers of her, how she performs her role within a more specialised one and what she appears or desires to appear to be or act, and by what authority – ‘map or guidebook’:

And I wondered: was it the case that I had some need to be observed in this way: writing – thinking deeply apparently – …, while others were relaxing and enjoying what was around them. “Is she a writer?” Is this what I want people to ask themselves?[17]

Yet presumably, only the italicised phrases were written in the notebook. Often written-down or ‘noted’ phenomena are registered in different places and conflict, such as in the exchanged messages with Tom, her ex-husband) – some typed in text to him. Others privately recorded in the notebook, some of uncertain status, and which starts with Tom’s written telephone-text to her:

… That incredible night. Do you remember it? I remembered the night had become to be known as The Incredible Night, and I remembered the ingredients of its incredibleness: the huge sound, the blazing stage ,… Of course, I replied, then noted: A memory of no atmosphere. A scene observed – experienced by someone else. I possess it, but am not in it. Before I closed the notebook, another message arrived.[18]

How complex is our reading here of context and notation – between the places (all harbours but in different places and at different times) wherein writing occurs or words and meanings are generated, interpreted (often in ways that clash dialectically with each other silently or in conscious debate). It is in such contexts impossible to know from whence emotion derived, if indeed it did, or whether it is confabulated (see my blog on this) – invented to fill a vacancy:

A memory of contentment; sitting at the harbour at Lynmouth, voluptuously tired, after miles of walking. Some of that contentment was borrowed from the contentment of the present moment, but some belonged to the recovered day itself. …[19]

Likewise we never meet Petros without there being at least two Petros’s present in the recording of each visit – one from each visit to the town being present to the writerly mind and interacting with each other and their respective dogs, with beautifully complex shift of times, spaces, scenery and dramatis personae.[20] These interactions often occur in what seems at first to be a simple sentence but is not: ‘He had known nine years ago, that something significant had recently occurred, he told me now’. Try as one might, it is difficult to locate that ‘recently’ in meaningful time-space.[21] This is a difficult blog to write I think because the terms of reference of the novel and/or narrator themselves cross, innocently or otherwise, so many domains of knowledge, action and identity. I have mentioned many already – therapeutic counselling theory and practice, law, philosophy (and jurisprudence particularly to unite the two on questions of judgement and punishment, religion – from many traditions, psychology and philosophy with crossover between all the other domains. People often lose each other in their discourse – straining to find the appropriate meaning in a discourse, even in social terms as we have seen. With respect to the more ‘heavy’ material with institutional authority behind it, people often seem to see themselves as struggling to be qualified to understand each other, as in the telling moment where Patrick, the novelist friend of the narrator, refers to the discussions between the narrator and Petros that he has read regarding the question of personal identity and its application to the narrator herself:

It’s an incredibly difficult subject and philosophers who have applied themselves to it have been tying themselves in knots for centuries, says Patrick. “And neither of us is a philosopher”.[22]

As always the quotations are of such complexity that their potential to varied application of meaning refuses to close down – and I think this one reason why the narrator so freely mixes indirectly reported speech with direct quotation. Here the philosophy of identity is reduced to philosophers ‘tying themselves in knots’, where identity is the very thing that gets knotty and complicatedly intertwined from many threads, as, I believe, it does in the book. It is though, ass if, philosophical statement hangs from every conversation. That is most obviously so in that conversation with Petros referred to already twice above. The narrator struggles to respond to Petros’ insistence that identity is proven by continuities in the self without caring to argue the point or tie ‘himself in knots’, but the struggle does not truly occur in the reported conversation and the narrator summarises only what that dialectical event ought to have been thus, after the event, so to speak. People differ she wants to say but doesn’t say very clearly, tying herself in knots with the example of a putative X and Y to stand for different persons in terms of their culpability for misdemeanour like violence because for some the ‘brew of chemicals’ in the brain made them the kind of person ’for whom those ideas’ (of distinguishing ethically right or wrong actions) ‘were powerless’. And she thinks she ought to have insisted on the fact that persons are not created in themselves by themselves, or in her terms: ‘We are not our own cause – I made a note of this, for future use’.[23]

The argument is sort of Aristotelian: comparing the final causes of teleology with the divine (or prescribed ones) causes – imperatives – of deontology, but I am not a philosopher either and I can’t run with that statement to any justification of it. My point is that the narrator is constantly ‘philosophising’ about something, not least the nature of making decisions and choices ethically and the nature of both judgement, and where called for by those judgements, punishments. This appears to be the issue in the X any parable or thought experiment referred to above, which distinguishes the ethics of violent acts between persons of different moral constitution. This is the stuff Patrick wants to make the novel of, and is his reason for seeing Stephen Staunton, the man who killed Hohn’s daughter’s son, Gareth over a fight about a woman they both liked. Though Petros is called this to Hellenise his name Peter, he is sometimes hinted to be Stephen. Patrick calls him ‘Petros / Stephen’, and his fall into a mechanic’s pit hinted possibly to be a punishment for Stephen, as promised by Gareth’s grandfather, John.

But none of those connections are clearly stated or narrated – they live in suppositions from hints in character dialogue, or the obscurities in the narrator’s story-telling sometimes. To complicate things further Petros has a criminal brother, raising the issue of a doppelgänger relation between the philosophic and angry Petros, who is also Arina (Niko’s wife on the second visit) suggests a ‘rock’ or stone foundation (the meaning of the word Peter/Petros’) in reading one of his poems to the narrator: “A stone / a word / a rock / a word / a stone / a word / a stone / a word”. After reading it this ‘column of short lines’ Arina says: “He is good with cars. That is what he should do. Only cars,” ….’.[24] No-one could ever be enlightened by the jurisprudence contained in the book, just sure that its arguments around moral action, judgement and punishment are well rehearsed and performed.

And I think this is so with the metaphysical concerns in the novel’s interactions – including those between narrator and reader’ over the nature of time and space, invited even the opening sentence: ‘The first time, the intention was simply to find a place that was quiet, but not somnolent’. At first search we seek a space that is already pre-imagined for a purpose described almost as scientific (or at least to do with knowledge acquisition) in its purpose, almost like a stage setting for a play or a scenario for a thought experiment such as one of Plato’s dialogues, though not an over-populated one:

During the stay, I would put my thoughts in order. I had pictured where this procedure would be carried out: a small square, the focal point, with café tables in the shade of a huge plane tree, an assortment of shops, whitewashed walls, the small hotel in which I would stay’.[25]

He word that stands out here is ‘stay’: the rest of the novel being a kind of dialectic which make person ‘stat’ in one space through time, or ‘move on’ with it to new unimagined spaces, physically and mentally. Does anything ‘stay’: this is the burden of the dialectic throughout and why the novel is structured complexly about the memories that congregate around two visits to one space in two time frames. Later, she will seem to collect all time into that one space – not just the two visits. As she leaves it she thinks that all ‘the hours I had spent in this square were in it, not as distinct components, but as elements of a compound, …’.

Yet such moments of pooling of past and present (and future) in a ‘Still Life with Townspeople ’[26]are a kind of lie that magical thinking creates. Even at the outset she learns that even if you ‘stay’ in one space, time is not stilled:

I walked on, out of town, to Petros’s garage. A house now stood where the garage had been. It was definitely the same spot – I remembered the church, the view of the conical hill, the aqueduct. An element of the return, a huge reversal, right at the start.[27]

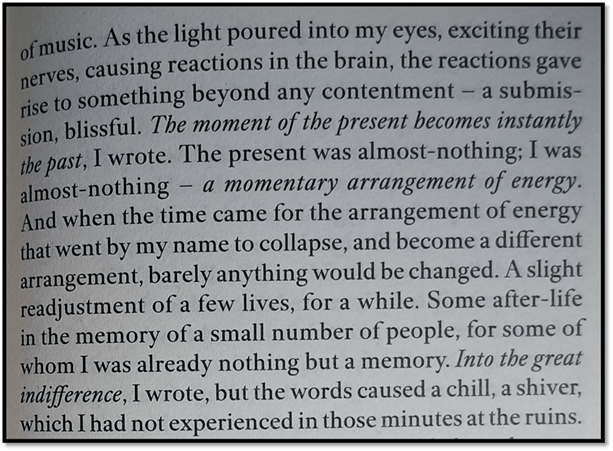

‘Still Lifes’ are artist’s fictions and much suffer reversal in observation of the life of even small relatively unmoved communities. At most time is still when considered as a palimpsest of events and people recorded over each other. And this is what the narrator continually tries to inhabit, even when she has to go underwater to find it. The history of the town includes the Mycenaean age, with its global links – Crete and Mycenae, the Byzantine Empire, Venetian hegemony, the Ottoman Empire, and the Greek War of Independence, and characters that recall as if kin Homer, Pericles, and Alexander. . Thinking of the violence of the Petros scene in his garage at one point Niko remembers the discovery of a seal, three and a half thousand years old with ‘two fighting warriors’, and the Griffin Warriors tomb whence it came.[28] At her first meeting with John, the discover whether both were interested in the ‘ruins of the Mycenaean Palace that is like Knossos in Crete, running on into ‘the shoddy quality of many Byzantine buildings’.[29] A major scene occurs in an underwater archaeological dive. Turned into the stuff of philosophy this leads to that beautiful moment of ataraxia I have cited before. It is a moment when we desire time to fuse, as it does in music – in the well-worn manner explored in modernism, notably T.S. Eliot’s The Four Quartets.[30]

My own feeling about this is that this modernist moment with the religiosity of some modernisms is only yet another temporary position taken up in this book, which summarises every reaction ever made in literature to the dialect of characters who move on to become the flow of life itself, those who stay put pretending to a temporal status of an enduring type and all the variations in between those false binaries.

But my head aches now and I have said all I can say, except that this book is more than remarkable. It too is a contender and a very strong one. I love it.

All my love

Steven xxxxxx

My draft title below

[1] Jonathan Buckley (2025: 166) One Boat, London, Fitzcarraldo Editions

[2] Ibid: 95 – 98

[3] Ibid:98f.

[4] Ibid: 166

[5] Ibid: 101f.

[6] Ibid: 125

[7] Ibid 155f.

[8] Ibid: 24

[9] Ibid: 85

[10] See ibid: 52f. on the non-binary fluidity of how the narrator is perceived.

[11] Ibid: 146 – 149 variously

[12] Ibid: 69f.

[13] Ibid: 117

[14] Ibid: 18

[15] Ibid: 13f.

[16] Ibid: 76 & 163 respectively

[17] Ibid: 25

[18] Ibid: 14

[19] Ibid: 15

[20] See ibid: 84

[21] Ibid: 134

[22] Ibid: 164f.

[23] Ibid: 129

[24] Ibid: 76

[25] Ibid: 11

[26] Ibid: 157

[27] Ibid: 19

[28] Ibid: 106f.

[29] Ibid: 29f.

[30] The photograph is from ibid: 125

One thought on “This is a blog on the rich novel that is Jonathan Buckley’s (2025) ‘One Boat’.”