‘The phrase Çdo gjë është e shrkruar – Everything is already written – came to mind. Albanians usually offered it to an anxious person for comfort, as a reminder that the cogs of some future event had been spinning since the beginning of time’.[1] This is a blog on the translation and interpretation of East European migrant experience to America in Ledia Xhoga (2025) Misinterpretation London, Daunt Books (the US edition came out in 2024).

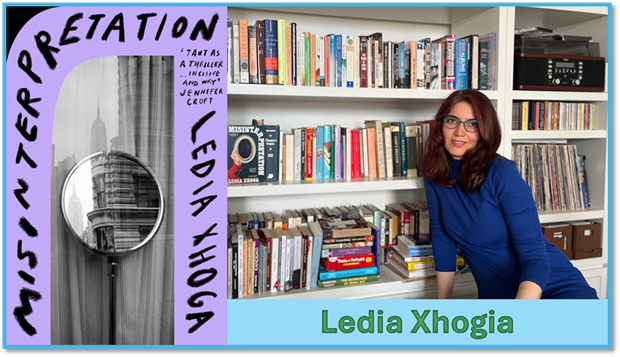

The unnamed narrator of Xhoga’s novel returns to the office of Zinovia, the first name of the psychiatrist (at the end of the novel Misinterpretation). Zinovia had put on hold the narrator’s career as an interpreter, and we might expect that, as a result she would be on her best behaviour (even when alone) preparing to see this authority who can restart her working life. Yet on finding Zinovia’s office open and Zinovia absent, the narrator scans the personal photographs, even one placed ‘facedown’ and thinks it likely that Zinovia might not ‘want her patients to do what I was doing, stealing a glimpse at her private life’. Yet though she thinks that that does not stop her from sitting at Zanobia’s desk, opening its drawers and examining their contents.

One drawer reminds the narrator of a similar one of her mother’s, and forces from her an old memory stored away in one of her own psychic drawers of her similar drawer in her mother’s house. Now she has only recently returned from visiting her now reclusive mother in Tirana and when she remembers the drawer it is unclear when her memory of it comes from – the recent visit to her widowed mother where she had looked at the drawer, or the first look many years ago when she was a child and her father still alive, or has confused that drawer with the one she is searching illicitly now, in Zanobia’s office. And, at the centre of this complex of linked events in her mind is her father’s statement to her:

We’re in the same room, but you don’t see or listen to me at all.[2]

Here then is a novel about the nuances of intercommunication, even in the privacy of one’s own memorial consciousness with figures whose co-presence with one is uncertain or their absence assumed in order to talk at all. And it is appropriate that this be investigated in a novel in which the protagonist, the same unnamed narrator, is both a ‘translator’ and an ‘interpreter’. Strangely, one of the best reviews I have read of this novel is by an Albanian-origin student at the American Wesleyan University, Arla Hoxha. She says something I feel might be a good start for us to investigate the issues in the novel about communication and miscommunication, community or its absence and the roots of the wrongs that arise from misinterpretation of otherness. The Hoxha says:

Novels centering (sic.) translators have constituted a sub-genre in literary fiction in the past few years. … Xhoga joins this sub-genre by discussing not translation, but interpretation. If translation is a collaboration, usually of a literary nature, an interpretation is full embodiment of the other that is being interpreted. The interpreter does not simply translate Alfred’s words; she allows him to speak through her, and sometimes speaks for him in turn. However, Xhoga’s interpreter learns to let go of others’ views of who she is; to not be absorbed into the selves of others, but instead to construct her own self.

In fact the distinction between translation and interpretation is in the novel: when, under Zenobia’s advice, her employers suspend the narrator’s right to work for them as an ‘interpreter’ they exempt translation work, because it does not involve interactions between people who are co-present to each other.[3] The misinterpretation in this novel are occasionally about the mistranslation of a word but the error of interpretation most often lies in the misreading of the presence or absence of another in the room – in speaking inappropriately for another or inappropriately when you yourself ought to be inhabiting a rather different role, performing as another than ‘oneself’. In fact Hoxha is spot on about this in her piece. She tells us – rightly I think – that the narrator has a very insecure sense of self, often taking on the characteristics of other – like Alfred, or projecting her characteristics (even perhaps hallucinatory experience) on them and /or introjecting theirs. Hoxha might have given more evidence but she is right nevertheless about the narrator:

It becomes difficult for the reader to tell which realities belong to whom. The protagonist is left nameless by the author, to allow for easier assimilation. Alfred’s presence becomes stronger with every interaction, soon inspiring a shift in the protagonist, a desire to break off with comfort. She observes this change in her relationships: Cracks in her marriage finally break open, and acquaintances quickly turn into friends.

Xhoga’s narrative voice also slips into unreliability; did she really see something or is her perception deluding her? Did she say that or did someone else?

“Did you feel the same way?” I said in Albanian.

Because I was interested in the answer, I worried for a moment that the question wasn’t Zinovia’s but my own. It was absurd. Of course, she must have asked it first. I should have left it alone, but the doubt kept gnawing at me. Zinovia would have interrupted. She would have told me it wasn’t my place to ask questions. She appeared unflustered.

In this scene the interpreter asks Alfred a question, without being certain that it is coming from the therapist. The narrator floats in and out of consciousness, making it difficult to discern if what is being described is actually happening. She lives a double life, oscillating between a state of deep intimacy and complete isolation. In a culmination of incredulity, the protagonist sees an old friend in the park and starts dancing with her and dozens of oddly dressed strangers, while an elderly gentleman plays a piano that appears seemingly out of nowhere— “How had he brought the piano into the park?” The narrative takes on these extreme positions to demonstrate to the reader how easily one can incorrectly interpret a situation.[4]

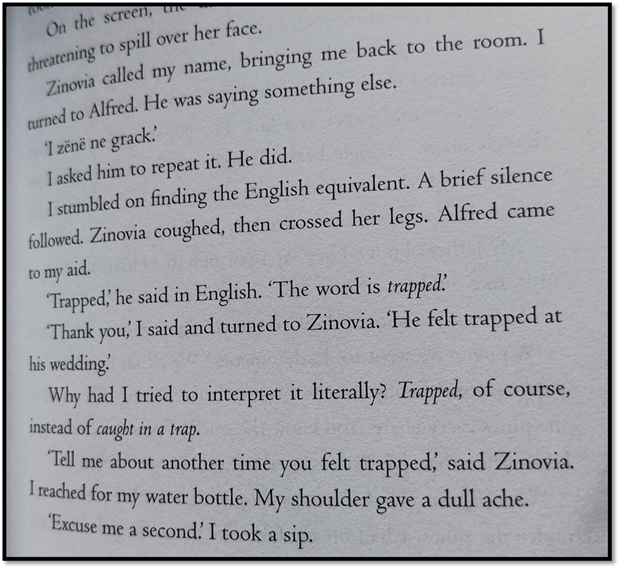

Hoxha’s last sentence falls into a kind of bathos, for what this clever student has actually noticed is the often hallucinatory nature of the novel, and not just when Alfred, the Albanian torture victim and émigré, who sees talking ‘wild, disfigured hybrid animals’ in pursuit of him.[5] Very often the narrator overplays or becomes overinvested in a role she is playing, such as when she begins to enjoy the sexual interest in her of the awful Rakan, the man who is abusing her friend Leyla, and takes kisses from him whilst noticing the yellow teeth in his smoke-wracked mouth, finding it ‘disgusting’, whilst ‘extending my tongue to meet his as our mouths come together’.[6] In the interpreting session – interpreting for Alfred for Zinovia – the one translation slip is based on extending the meaning of a word to convey the agency of others in capturing you within a marriage relationship – as if she were inventing the scenario for Alfred. It is a fascinating scene for it starts with Zinovia saying something very like the memory she will later have in Zinovia’s office that her father accused her of not being in the ‘same room’ as her interlocutors and thus negating their independent presence:[7]

There is such fluidity here in the realities the narrator records – and such privacy of intention. Despite my attempt above, is it clear why she believes ‘trapped’ and ‘caught in a trap’ differ, except that this is very moment where she proves to Zenovia she is currently unfit for psychiatric interpreting work. As she recounts that story again in the agency for which she works as an interpreter, she detects a repeated occurrence of feeling to be interpreted by others by feelings that ‘something was wrong with me’.[8]

Having seen this feature of a rather novel kind of unreliable narrator in the stories of this book, opens all the interactions we read of in it up to doubt, even with regard to the oft unexplained absences and sudden reappearances of characters who come and go in ways that are often both overinterpreted and perhaps delusions. This is also evident in the invocation often of minor characters who have no real role in the stories told, such as the fact that she ‘once interpreted for a charismatic Italian psychic who specialised in auras’. The narrator denies seeing the coloured auras this psychic promised she would do but nevertheless feels that she lives in anticipation of ‘an occasional sense of composure, a transitory calmness when things were about to work out in my favour’.[9] If her sense of reality is impaired, then so is that of the stories told as if in the mouth of characters that she may embellish with her on fantasies, such as her husband’s fascination with the surveillance of bridges, that will play a major part in this narrative. One such bridge that does exist is the bridge at Berat, the Gorica Bridge, where the narrator again meets up with her husband, the American University Professor, Billy. The bridge is interpreted as by an Albanian legend of two brothers in love with the same woman.[10]

Gorica bridge over river Osum by Karelj – Own work – The Gorica Bridge over the river Osum in the town Berat, central Albania, September 2018 – CC BY-SA 4.0

Bridges are meant to allow things to connect and communicate but in the legend keep things as far apart as they ever were. To the narrator the Gorica Bridge is a place she dreams of meeting Billy and then, fortuitously does. It all bears a hint of unreality, not unlike the bridge Billy is meant to have a role overlooking. It is of isolation not connection.[11] But bridges accumulate fantasy for the narrator too. Hearing that there was in ‘ancient legend’ a dungeon under the Gorica bridge where they would ‘incinerate young girls to appease the spirits responsible for the safety of the bridge’, when she meets Billy again she dreams of being taken to those very flames: ‘a roaring fire under the Gorica bridge’. [12] Always in the medium that connects the powerful, the narrator dreams of herself as the victim of those who want to keep any communication open even if she must be sacrificed to it. All of these fantasy undercurrents are difficult to subject to precise interpretation in this novel – for our own bridge to interpretation – the protagonist is faulty and continually punished for being so.

Likewise Albanian history lives in a kind of gap between fiction and reality, where truth lies in valiant interpretation of complexity. It serves, as Rome does to Dorothea in George Eliot’s Middlemarch as a heavy burden. If Dorothea feels the ‘weight of unintelligible Rome’ fall on her soul, the narrator finds:

Tirana was overwhelming as usual. Soon after landing I was convinced that the only life that mattered was the one here: unpredictable, complicated but truer than anything else. …

Yet the Albania she knows is a kind of projection of her family’s sense of their own importance: ‘Her uncle was preoccupied (or obsessed depending on who you asked) with our family’s role and position in Albanian history’. [13] Albanian history does not appear to be a safe space for the narrator. When reminded of her great-grandfather by a suddenly exposed portrait in a mirror behind here she sees in him only a ‘stubborn glare’.[14] These male ghosts are summed up in that of Enver Hoxhar, the last Communist tyrant of Albania, whose name seems impossible to erase but can be changed to say: N-E-V-E-R. At the moment of acknowledging that fact she remembers the sexual threat to her remaining from her time with Rakan.

I cannot interpret these strange runes, although there does seem a strangely inarticulate fear of Albania associated with its men where love and hate are continually at play with resistance to power and oppression by it. Are the Albanian sections in some way related to the strange appearances and disappearances of the political refugee, Alfred, and the weird attraction of the oppressor Rakan? I don’t know the answer to this question. But this does not mean I consider this novel incoherent – just because it does not off me easy readings. There are elements of it that are magnificent and all of it reads well and maintains one’s interest in it. But unlike others, it is more obviously a debut novel that announces rather than establishes a career in the making.

The piece I chose for my title is one magnificent moment in the novel. Is there irony in the sentences:

The phrase Çdo gjë është e shrkruar – Everything is already written – came to mind. Albanians usually offered it to an anxious person for comfort, as a reminder that the cogs of some future event had been spinning since the beginning of time.[15]

There may be a deep irony here – for when things are ‘already written’ they do not imply the steady course of a fixed predictive narrative will follow as sure as night follows day. Instead written things have to be read – and in reading we translate and reinterpret and then apply to a specific context that may shift the meanings already there. Most of the interpretations we make are designed to ‘comfort’ us as the Albanians use their phrase, but though a thing is already written, we might still have the right to read with a different slant to its meaning and application.

The court is out for me – I do not consider the book a must for the shortlist – but only because it does not for me feel to have the heft that such a novel should do. But – I have been wrong before. I am open to ideas from others.

Let’s see how it fares in Booker.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Ledia Xhoga (2025: 239) Misinterpretation London, Daunt Books.

[2] Ibid: 315

[3] Ibid: 98

[4] Arla Hoxha (2024) Review: Misinterpretation – Ledia Xhoga in Full Stop (online) [October 18, 2024] Available at: https://www.full-stop.net/2024/10/18/reviews/arlahoxha/misinterpretation-ledia-xhoga/ The italicised quotation is unpaginated but comes from Ledia Xhoga, op.cit: 60.

[5] Ibid: 61

[6] Ledia Xhoga, op.cit: 149

[7] Ibid: 61

[8] Ibid: 97

[9] Ibid: 266

[10] Ibid: 193f.

[11] Ibid: 208f.

[12] Ibid: 194 & 210 respectively.

[13] Ibid: 159f.

[14] Ibid: 171

[15] ibid: 239.

One thought on “This is a blog on the translation and interpretation of East European migrant experience to America in Ledia Xhoga (2025) ‘Misinterpretation’.”