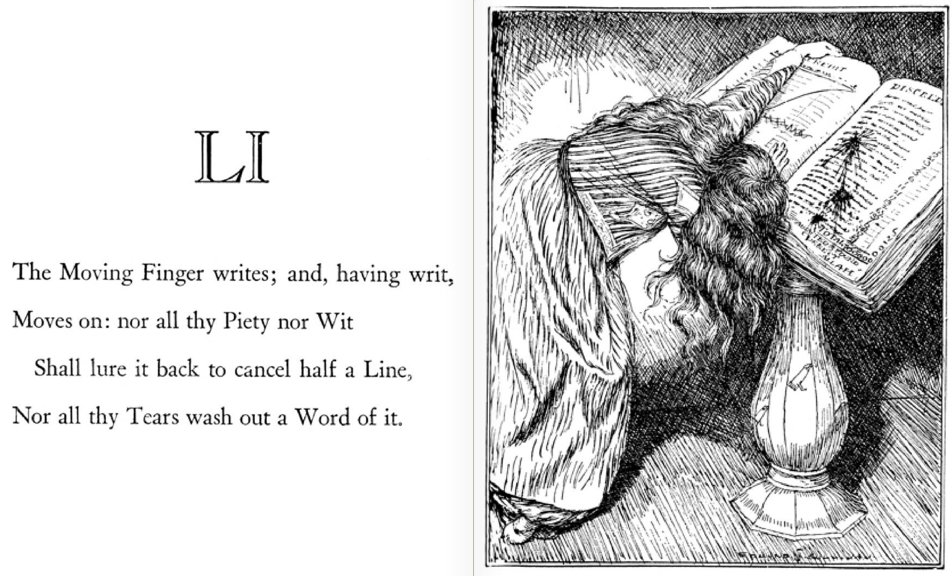

The best known quatrain of Persian Poetry, in stolid Victorian translation is that from what The Poetry Foundation calls the ‘Rubáiyát, his collection of hundreds of quatrains (or rubais), was first translated from Farsi into English in 1859 by Edward Fitzgerald’, attributed to Omar Khayyam. There are versions on versions of the quatrains translated, not least by Fitzgerald . This is the best know. I found the claimed Farsi version from which it is taken and transcribe it below Fitzgerald’s English but I cannot read it:

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.

بر لوح نشان بودنیها بودهاست

پیوسته قلم ز نیک و بد فرسودهاست

در روز ازل هر آنچه بایست بداد

غم خوردن و کوشیدن ما بیهودهاست

Juan Cole translates it very differently:

The judgement of fate's pen cannot be changed,

and grieving causes only further pain.

for even if you brood throughout your life,

you can't affect your destiny one bit.

The concept of writing is implied rather than named in Cole’s translation merely by the mention of a pen held by ‘fate’. In Fitzgerald’s version you feel the motion endemic to the act of writing, a kind of motion committing itself to something that will remain once it ‘moves on’. The text that forms the ‘judgement’ on you will remain and will forever mean the same – hence you might as well accept it now and ‘move on’ too.

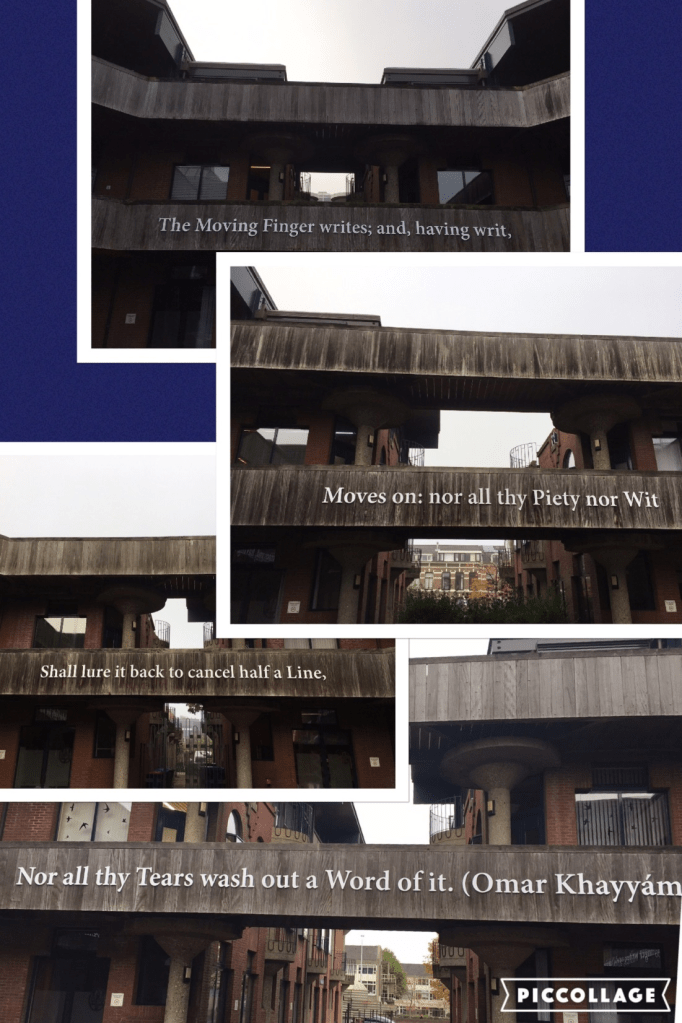

Even Fitzgerald’s version when inscribed on something with claims to durability, will have that proud sense that the person or the thing the writer actually writes will outlast the thing or person itself. Even brutalist architecture can be made to bear that meaning though it itself has not proven enduring in many instances. And sometimes, some things we do not want to endure – the force of attempting to ‘wash out’ stains in this verse, emphasised in the heading illustration where a young women wants to erase a fault or ‘sin’.

But let’s take another poet – in a lyric published nine years before Fitzgerald’s translation, by Alfred Tennyson in In Memoriam and therein expressing his fears about, rather than hopes and belief in, his own writing:

What hope is here for modern rhyme

To him, who turns a musing eye

On songs, and deeds, and lives, that lie

Foreshorten'd in the tract of time?

These mortal lullabies of pain

May bind a book, may line a box,

May serve to curl a maiden's locks;

Or when a thousand moons shall wane

A man upon a stall may find,

And, passing, turn the page that tells

A grief, then changed to something else,

Sung by a long-forgotten mind.

But what of that? My darken'd ways

Shall ring with music all the same;

To breathe my loss is more than fame,

To utter love more sweet than praise.

That you believe ‘writing; lasts is an illusion, Tennyson sings, though the poets is not now an august personification of ‘fate’ or ‘destiny’. Verse writing gets forgotten and neglected – the paper it is written on has more value in an everyday use – binding another book or even as implements of hair fashioning. The thing about writing is not that it remains whilst the writer ‘moves on’ but is too ‘passing’. And even if read later will not, and indeed cannot, men that same as when it was penned – ‘grief’ gets ‘changed to something else’. Nothing is as big as it looks when we write it, for it gets ‘foreshorten’d in the tract of time’, just as an item in a painting is foreshortened in the long distance implied by painterly perspective, that creates the illusion of distance.

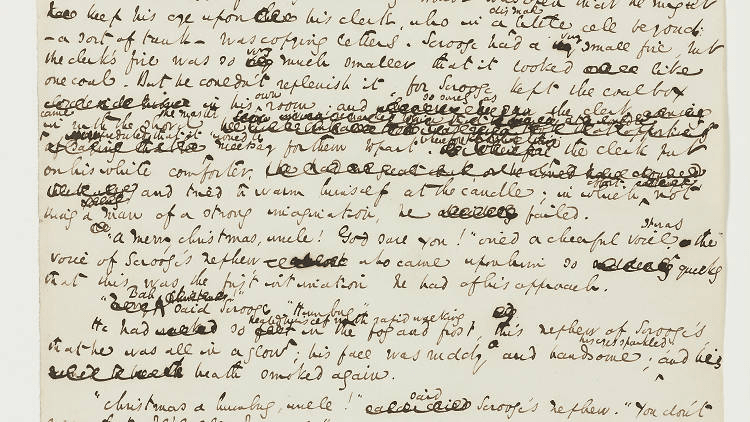

And Tennyson is right about writing whether it is a verb or a noun. What we love about writing is that, if we care about it, we do not just ‘move on’. Even in the process we move backwards over our lines of writing (to the left if in English, to the right in Farsi) to ‘cancel’ or erase a phrase or word with a possible unforeseen association we now want rid of, or less elegant than ee hoped. We amend the text – edit away,. Thus Dickens in one manuscript of A Christmas Carol:

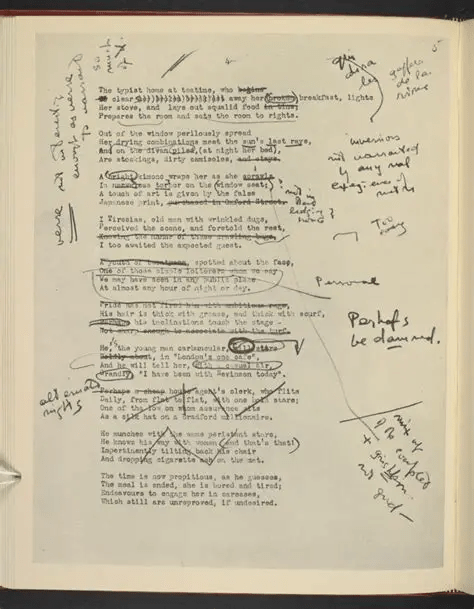

And famously T.S. Eliot in The Waste Land:

If even in the process of ‘writing’ we go back so often, what of the fact, as Tennyson hints, that when we read a writer who is ‘a long-forgotten mind’ our reading of what they meant is necessarily ‘changed’, because words have change their connotative, and sometimes denotative, meaning over time.

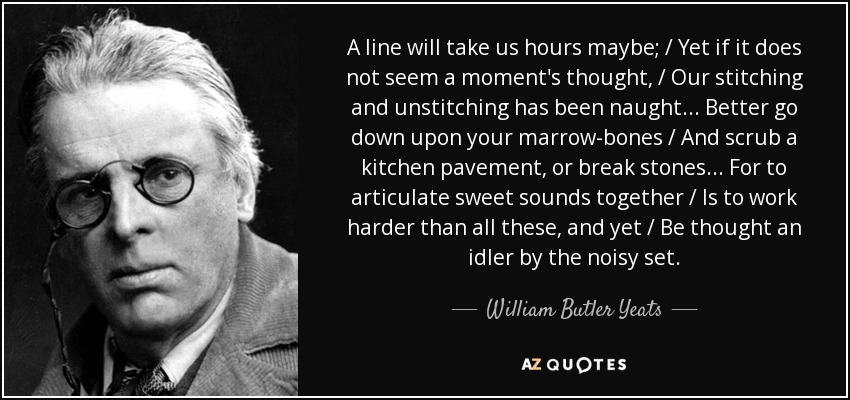

Indeed what I love about writing as a process is that it combines editing with construction purposes in its meaning – those second thoughts that improve on a word, syntax or rhythm (or other sound component) of a line of verse or prose. Witness William Butler Yeats Adam’s Curse:

Yet the whole point of Adam’s Curse, as a poem, is that however we labour to write or even express orally, high thought worthy of lasting, they pass – move on – for that is Adam’s Curse – the fall that brought motality into the world brings with it the impossibility of the infinitely enduring and expansive, whether heaven-on-earth, or our love:

I had a thought for no one's but your ears:

That you were beautiful, and that I strove

To love you in the old high way of love;

That it had all seemed happy, and yet we'd grown

As weary-hearted as that hollow moon.

Are we all as ‘weary-hearted as that hollow moon” is even the moon itself failing to be our ideal. If that is so, should we stop writing. No. For in a sense the fact that we ‘move on’ implies that we tire of expressions that are in time found inadequate and must change their meaning – but how will we have a record of this process if we all stop writing (avoid using the verb too) and bring ‘writing’ (the noun) to its apocalyptic end – and howwill we show that writing is never a matter of petty personality but an attempt to cross ever wider gaps with a newe kinds of possible being, which forever changes.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx