‘She felt a small pang of resentment: the endling’s last moments on Earth, and it pined over not getting laid. Of course this was normal. If anything, endlings should pine all the louder for the end of their species. … // At least gastropods yearned in silence, …’.[1] This is a blog on the role of endings in the modern metafictional novel and the light shed on that role by Maria Reva (2025) Endling London, Virago Press.

In truth I am still quite a long way from determining whether I liked or enjoyed Maria Reva’s Booker longlisted novel, Endling. However, you can’t read to the end of it at all unless you have some empathy for the metafictional novel – the kind of novel that not only invents fictional stories but does so in a way that we ae constantly facing all the issues fictional writing throws up, but within the fiction of the novel’s multiple stories, of which one story is that of how Endling gets written by a character who passes themselves off as its author . The most straightforward statement on this I have read is by Carole V. Bell in The Los Angeles Times, although I would call the novel a ‘puzzling’ rather than a difficult read. In most of the ways a novel can be described as ‘readable’ this novel definitely is, despite taking on the meaning of post-Soviet Russian wars in states now independent of it, the experience of emigres, the commodification of marriage, the role of direct action in the combat of social evils and pace of current rates of species’ extinction, particularly mollusks. Bell says:

“Endling” isn’t an easy read, but it is brilliant and heart-stopping. Authorial interludes can feel like interruptions, but by breaking the fourth wall, Reva forces us to pay attention to the ongoing devastation behind the narrative while unpacking the compromises of storytelling. Plus, Yeva, Nastia and Pasha and the merchants of romance spin their own fictions: They have trouble telling the difference between truth and make-believe even as the sounds of war grow near and even when bullets penetrate flesh.

This building up and breaking down of artifice forces reflection on how we use fiction to explore and bend reality while undermining the comforts of distance. As the author confesses, “I need to keep fact and fiction straight, but they keep blurring together.”[2]

But let us be clear, the author has only one section she calls an ‘interlude’; otherwise she allows the whole convention of the structuring not only of stories but of the shape of the books that contain them to be up for grabs. At the end of Chapter 14, the second chapter of Part II of the book, the word END is centred on the page. We turn over to find one and a half pages of ‘Acknowledgements’ , in which persons and books mentioned are most often fictional. This is followed by a centred small-font text on its own page ‘ABOUT THE AUTHOR’ and after that ‘A NOTE ON THE TEXT’, which invents a fictional font in which the book is typed, a history of it and its supposed inventor and a rationale that crosses the boundary between printing text, and understanding its relationship to the fictive authority of books as integrated wholes:

…, this type displays the tireless qualities of a master craftsman intent on weaving letter to letter, sentence to sentence, chapter to chapter, to create a sense of cohesion or an illusion thereof.[3]

Had we been doing our job as readers, we would have noticed that Chapter 14 from its beginning advertises itself as very likely to be an unauthoritative and false ending – for ‘happy endings’ might be precisely the biggest fiction in the whole industry of fictional storytelling and publishing, as in the Ukrainian marriage industry and market which has been the book’s subject thus far, mainly.

Here’s how it all ends: happily, believably.[4]

In fact the chapter takes up another subject of the text, one spoken in a preceding chapter end which is in the form of the text of a spoof application form to the Commonwealth Arts Foundation (CAF) made by a ‘Maria Reva’ ostensibly to engage in research in Ukraine but also as another ‘goal of the trip’ seeking out her ‘grandfather, the last of my relatives to remain in Kherson, and drag him to safety’.[5] Here is another ‘endling’ of importance. In Chapter 14, is helped out of his apartment and escapes to safety. Moreover the other stray ends of the narrative of Part I are given a semi-happy ending in that it ends with the kidnapped ‘bachelors’ from the Ukraine marriage industry being given ‘barley soup’.[6]

But, of course, the reader knows they are less than half way through the book – a stack of pages remain after the deceptive and we launch into a fantasy dialogue likening the making of whole coherent novels to the stitching together of several modern yurts into one unit. This over, we turn into Part III, only to find we are in Chapter 14 again, now called ‘Redux’ (brought back or recovered) and in the form of the minutes of a meeting between the central female characters. By Chapter 15, it is clear that the bachelors are still locked into the trailer that Yeva calls her ‘mobile lab’, with Reva’s grandfather no longer an item in the narrative.

But as the narrative turns on itself and the characters find themselves ending up not to the Carpathians to mount an exit from Ukraine but in Kherson (for reasons we can discuss later) where eventually the grandfather (but now of the character Masha who runs the marriage agency) is again a part of the story. However, though his ‘rescue’ is dealt with in 4 different versions of Chapter 44, in none of these does the Grandfather choose to leave Kherson. (Chapter ‘44’, ‘44, Again’, ’44, Revisited’ and ’44, Correctly This Time’. The final one sees the exit of the grandfather – in this chapter Reva-as-narrator is the granddaughter again – as dependent on the novelist and their narrators or agents (people with a specific point of view in the narrative) as responsible for the success of that venture: ‘If I get the details just right, my grandfather will leave Kherson’.[7]

Clearly metafiction can deal not only with speculation on the boundaries of fiction and reality, but also the devices and conventions that are unique to fiction, as indeed the early novel showed – Henry Fielding having a Chapter (Book II, Chapter 1) on chapters in Joseph Andrews. But modern metafiction can be tiring, especially when the history that is fictionalised is so contemporary – the history of Ukraine from 2022. Everyone is subject to fictionalisations of themselves – even President Yelensky, which mix fact with fiction. Bell expresses the dilemma thus, as already cited:

This building up and breaking down of artifice forces reflection on how we use fiction to explore and bend reality while undermining the comforts of distance. As the author confesses, “I need to keep fact and fiction straight, but they keep blurring together.”

If I understand her correctly, she is saying that it is a fact that we approach the ‘real’ in the real world too by modes of fiction, and that can both assist us in understanding but also bring historical realities too close, as in the gruesome genocidal murders depivted in the Kherson scenes. I am less sure of Bell’s take on the possibility that this book has an ethical position on all this. If so, Bell sees it in Yeva – as the novel points out the name is that of the Biblical Eve:

Yeva’s story gives the novel a melancholy moral center. And it’s from Yeva’s quest that the book derives its title: An “endling” is the last individual in a dying species, the kind she is dedicated to protecting. After losing access to institutional support, Yeva equipped the trailer as a roaming laboratory and storage site where (at the peak) she sustained over 270 species of rare gastropods. Though she prefers mollusks to men, it’s Yeva who insists on reducing the kidnapping target from 100 to 12, a number that the trailer could humanely accommodate.[8]

If she is correct, many characters have a life-quest different from each other that is engineered for them in the kidnapping of marriage market bachelors in Yeva’s mobile – lab. An indeed it is Yeva who mediates to us the theme of the ‘endling’, correctly defined by Bell, but I think Bell fails to see the theme underlying two facts she mentions here:

- That Yeva is the centre of strong feelings for all species that are at risk of ‘species extinction’ but also that these feelings are based on the knowledge that the means of reproduction are the only gateway to a continuing species’ survival.

- That she herself, who cannot reproduce hermaphroditically, starts off by preferring ‘mollusks to men’.

There is here a central tension that is based on the fact that Yeva / Eve must learn to tolerate men, even sexually, just as she knows is her desire for the last of her endling samples – the snail she calls Lefty – because of the left-leaning whorls on its shell. Chapter 50, near the end, blends the shot by a Russian soldier that nearly kills Yeva (at the every end of Chapter 49) with the words: ‘The flesh splits, but there’s no pain’, to describe the means of sexual reproduction and the last potentially mating female of his species (in an acacia tree in Kherson). That female is discovered for her by the one man she might be interested in but yet veers away from – also a green conservationist, caring for an endling that is a ‘polar peeper frog with oversize childlike eyes’. The fact that endlings are the conservationist’s ‘babies’ should not escape us, especially in the childlike eyes and Yeva’s rather tired response to this demanding looking species. This is why I focused my blog on their interaction over Zoom (started that way because of Covid). The whole conversion is a coded romance wherein the conservationist suddenly ‘typed, in Latin’ to her: ‘Te amo’. We can only see Yeva as a moral centre (even a melancholy one) if we see her able to learn to give up her enmity to being part of the process of ‘getting laid’. This is the bit I quoted about the frog, ‘named Tutan-Tlingit for “hope”’. I find it rather problematic however that Yeva’s preference for asexuality is problematic in this moral paradigm, but it must be if this passage is to mean anything at all

On the eve of his death Tutan had sung for the first time in years, calling for a mate that didn’t exist. …

… She felt a small pang of resentment: the endling’s last moments on Earth, and it pined over not getting laid. Of course this was normal. If anything, endlings should pine all the louder for the end of their species. Yeva was the abnormal one.

“Isn’t Tutan’s song beautiful?” he texted.

At least gastropods yearned in silence, Yeva thought but but did not say.[9]

Of course my difficulty with this was the value given to deciding that Yeva was ‘abnormal’ in her resistance to sexual feeling and / or reproduction. What queer theory might make of this I hesitate to say, though I doubt that Reva does not see the joke here too. But there is a reason why even Yeva feels glad she doesn’t speak out loud some of her thoughts – notably the one about it being better for ‘endlings’ to yearn ‘in silence’.

This reason might be highlighted, for instance, when ultimately the bachelors are freed from the lab the women Yeva, Nastia and Sol keep them in, everyone (including the novelistic voice) celebrates in that they have been freed also from: ‘Their carnal desire. … And so, they did not need women’. Of course Reva is conscious that carnal desire is not only heteronormative, yet she adds a rider where again the tonal quality – and hence attitude implied – is comically ambivalent: ‘They most certainly would not be tempted by each other, either – don’t even think about it’.[10]

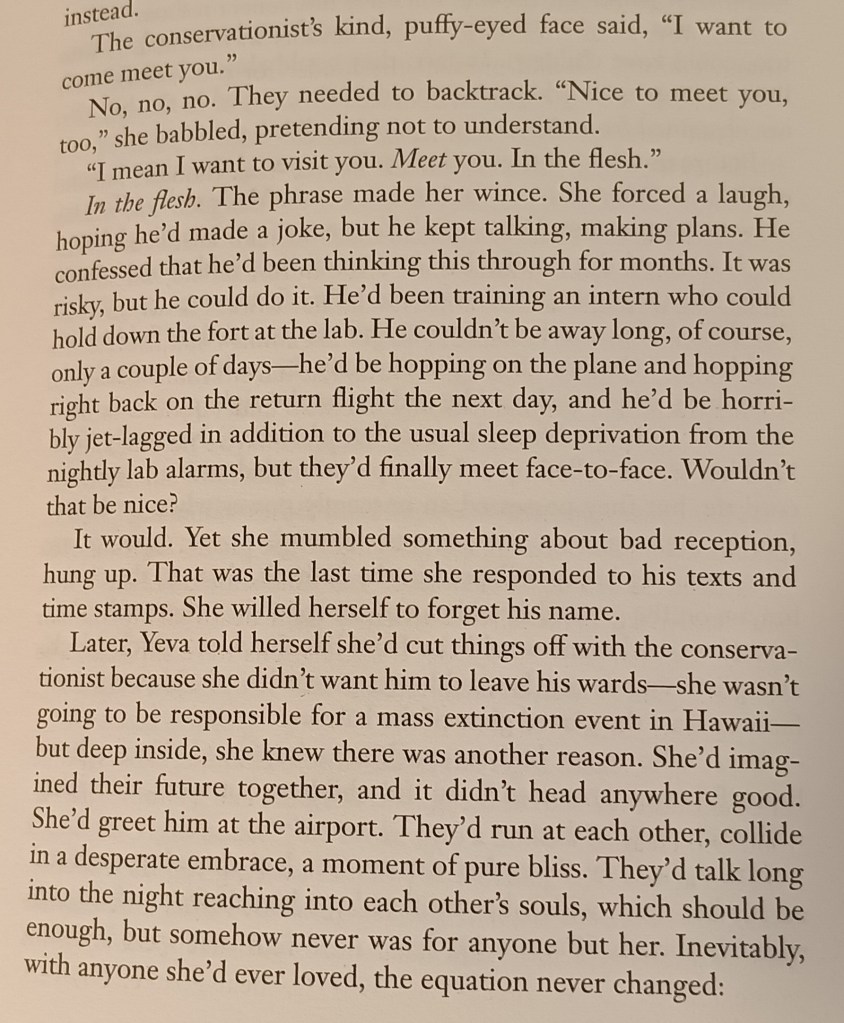

Can none of the bachelors have been gay, bisexual, trans or queer? We are told not to think, and that command is difficult to get tonally correct.That tonal problem is in later pieces of Yeva’s interaction with the conservationist with the ‘kind’ face. I have no doubt that Reva subjects Yeva to heavy irony because of her sensitivity to the term ‘In the flesh’. We are I think made to think her response pathological – and even she knows that she uses excuses like ‘pretending not to understand’ and denial to hid her closedness to people who don’t deserve such closedness. Of course, the thing about the novel is that endlings who do not want to reproduce still have that right, but in Yeva’s case she mistakes her role – as Eve, Mother of Humankind. In truth I think this strong hint to that interpretation weakens the novel for me. Let’s look at the passage I refer to:

The term ‘in the flesh’ is innocent enough – I have written about in relation to it being a staple term in art historical; discourse – see this blog if you wish. Yeva reacts to it as if it were an invitation to get naked and prepared for genital penetrative sex, regardless of intention and insight in its speaker. The equation she speaks of is on the turn of the page from the passage above:

I have genitals.

You have genitals.

Let's mash them together. [11]

Yeva projects the relationship into the sexual interaction she sees as inevitable and then reduces it to that. Now I think the case ought to be clear that asexual response is as valid as any other, although regarded as ‘queer’, but for Yeva it has to be labelled as ‘abnormal’. Is that because she introjects the heteronormativity around her or simply because there is something somewhat pathological or anti-human here. I think the novel poses the issue with that question open, whilst meanwhile poking gentle fun at how Yeva’s efforts to counter species extinction are presented as a kind of perversion of motherhood: the wasting of energy on the the ‘bottomless needs of 276 snails’, the object species of her care. Of course she has researched more than their needs – collecting facts about their species variations (including hermaphrodite species unlike Lefty) even down to snail mythologies. (12)

There is a version of the fantasising amoral that still calls for maturity to change it, in Piaget’s term ‘magical thinking’ (and this term is used in the novel (but can I find it again – no), Nevertheless examples of it are legion, not least the idea that Ukraine might be covered by an iron dome to protect it from Russian bombs and drones, or Bernard the Bachelor’s unshakable belief that the Ukraine war around them is a being playacted by actors – until he is shot to death. [13] This is as near as the novel gets to imagining immorality – the refusal to see the ‘realities’ of one’s species specific life: whether it be about species doomed to sexual reproduction mechanics (like humans and Lefty the snail), displacement and migration, war, ecological disaster, and the continuing drama of stories without endings, except for ‘endlings’., whose end is a ‘time-stamp’ or ‘death stamp’, a number when the last of your kind dies.

And yet look at the little cartoon in my opening picture which has a fairly accurate cartoon figuration of the characters of the novel, including Lefty – and the inaccurate title – Endlings not Endling. There is a sense that this is an accurate picture of at least the human characters – modern stereotypes of dispossessed youth and muddled female middle age. And I can’t rid myself of these prejudices about the book – that is tonally suspect in its support for normativity, stereotypical (The name Nastia (short for Anastasia – another endling of the Romanov dynasty variety) , after all, has to be pronounced to say ‘Nastier’) in its characters and rather overdoing its metafictional tropes. This is clearly a brilliant novel but not one for me. But I enjoyed large parts of it. honestly, it amuses even an unamusable mass like me. LOL.

With love

Steven

[1] Maria Reva (2025: 16) Endling London, Virago Press

[2] Carole V. Bell(2025) ‘Review: Fake brides have their own agenda in Ukraine native’s heart-stopping Endling’ in The Los Angeles Times (June 3, 2025 3 AM PT) Available at: https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/books/story/2025-06-03/endling-review-maria-reva-ukraine

[3] Maria Reva op.cit: 137 – as per convention the page is unnumbered.

[4] Ibid: 128

[5] Ibid: 126

[6] Ibid: 131

[7] See ibid: 291 – 297.

[8] Carole Bell, op.cit.

[9] Maria Reva op.cit: 16

[10] Ibid: 307

[11] ibid: 17f.

[12] ibid: 7 – 9

[13] ibid: 329 for one example

One thought on “This is a blog on the role of endings in the modern metafictional novel and the light shed on that role by Maria Reva (2025) ‘Endling’ London, Virago Press.”