The word ‘carry’ derives originally from the idea not on the personal capacity to bear something along with you on a journey but on the use of a ‘vehicle’ (‘from Latin “carrum” originally “two-wheeled Celtic war chariot), although the Celtic use itself bears the more difficult to reconcile association of “run”. Maybe the later etymology makes it easier to understand the association of ‘winning’, especially in warfare and electioneering. Yet the development of this single simple word , has, as etymonline.com shows below, taken wing into the realms of a personal virtue, skill or capacity:

carry (v.) : early 14c., “to bear or convey, take along or transport,” from Anglo-French carier “transport in a vehicle” or Old North French carrier “to cart, carry” (Modern French charrier), from Gallo-Roman *carrizare, from Late Latin carricare, from Latin carrum originally “two-wheeled Celtic war chariot,” from Gaulish (Celtic) karros, from PIE *krsos, from root *kers- “to run.”

The meaning “take by force, gain by effort” is from 1580s. The sense of “gain victory, bear to a successful conclusion” is from 1610s; specifically in reference to elections from 1848, American English.

The meaning “to conduct, manage” (often with an indefinite it) is from 1580s. The meaning “bear up and support” is from 1560s. The commercial sense of “keep in stock” is from 1848. In reference to mathematical operations from 1798. Of sound, “to be heard at a distance” by 1858.

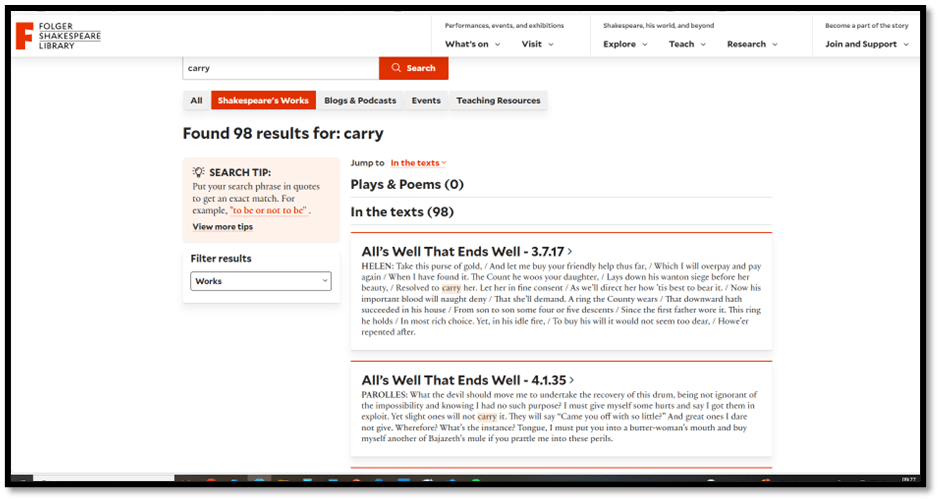

My expectation, which was I thought carried forward by memory, was that Shakespeare, if his works were searched searched again, would use the word mainly in the military sense, but using the Folger Library‘s online search engine in their wonderful edition of the works has proved me wrong. Most of the 98 uses were of carrying things according to your capacity

But two speeches use the word in contexts I want to steal for my purposes in this response to a prompt about ‘the most important thing I carry with’ me ‘all the time’. In a phrase, that thing is, I think, something I want to call an ’empathetic imagination’, a ‘power’ to see the power in others, however hidden (or latent) and nurture it to the best of its power of blatant self-esteem and capacity to do the things they might otherwise not see in themselves. This is the object in both of the careers I once had – teaching and social work – but doing it as a job role is an onerous thing, a demand that cannot be met too often. But I can only hope I would do this as a friend to friends – though sometimes self-interested things get in the way.

But the Shakespeare examples show that carrying such imagination is never less than ambivalent and oft polluted by self-interest or other motives – hidden sometimes even from those who have them under their carapace sometimes. Shakespeare’s examples are of actors speaking for a writer of plays to beg of them that power without which his object cannot be complete – the representation of grandeur – whether of great good, evil or mixed motives. Let’s look at the examples:

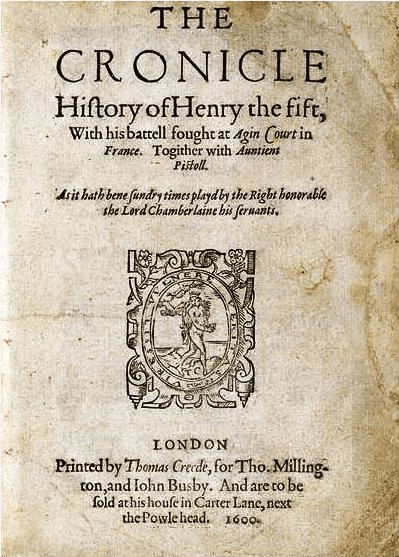

One is from the speech by a single man named as ‘Chorus’, as if he were many people in our imagination as in the tragedies of Greece (hence our co-operation as listeners starts from the get-go), in the ‘Prologue’ to Henry V (lines 24 and following) makes audiences the carrier of ‘imaginary puissance‘: a power or strength that can be imagined and elaborated upon only because of the strength of imagination of its audience that hear, see and complement both with extraordinarily powerful inner tools that carry weight beyond the capacity they thought they had. Nevertheless donkeys do no less with heroic burdens.

Piece out our imperfections with your thoughts.

Into a thousand parts divide one man,

And make imaginary puissance.

Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them

Printing their proud hoofs i’ th’ receiving earth,

For ’tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings,

Carry them here and there, jumping o’er times,

Turning th’ accomplishment of many years

Into an hourglass; for the which supply,

Admit me chorus to this history,

Who, prologue-like, your humble patience pray

Gently to hear, kindly to judge our play.

It is a strange piece of rhetoric this, which asks us as audience only latterly for gentleness, kindness and ‘humble patience’ from an audience, beforehand creating images of the imagination that is required of audiences. Those images are both violently brutal – dividing ‘one man’ into ‘a thousand parts’ – and strongly athletic – ‘jumping’ over obstacles – but yet in service to things greater than themselves – that can ‘deck’ their kings and overlords with their apparel, ‘carry’ them as if they were the burden -bearing horse and cart.

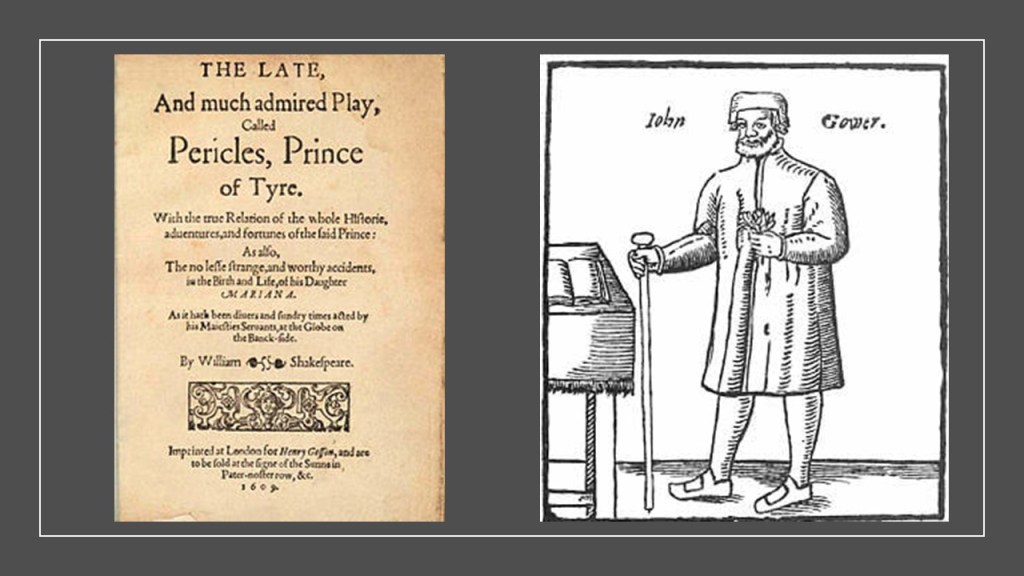

The idea is also in the lesser play, much as I love it personally more, Pericles, where the ‘chorus’ is now one man, but a known medieval poet – contemporary to Chaucer and another product of the Renaissance of courtly arts under Edward III – poet, John Gower. The Prologue to Act IV (lines 45 and following) mimics the ‘lame feet’ and the ‘rhyme’ of the latter’s narrative poetry, claiming the word ‘rhyme’ alone as the name of an archaic and lesser poetry. But again Gower is asking an audience that they indulge the lamed poet to help him ‘carry’ his characters (acting as avatar for Shakespeare himself), to use their own mental equipment to help carry burdens that he, being lame, cannot carry alone. The same plea is here to ‘imaginary puissance’ but not decked in such grandeur as the heroic content of Henry V, but popular tales of murder and rapine.

.... The unborn event

I do commend to your content.

Only I carry wingèd Time

Post on the lame feet of my rhyme,

Which never could I so convey

Unless your thoughts went on my way.

Dionyza does appear,

With Leonine, a murderer.

I love the way Gower is made to labour the image of the humble carrier by making himself appear more ‘umble (much like Uriah Heep in David Copperfield). Imagining the creations of Shakespeare though is good exercise for empathetic imagination, for here words on a page, or even figures on a stage get transformed. Of course, we believe the powers that get recreated lie distributed once used – in the poet, dramatist, and in the second example, directors,other design collaborators, and actors of the drama. And those words can alone carry us a long way -if we avoid simple self-interest or over-easy identification without the inner eye seeing the perils of such identification (though again the latter can be implicit in Shakespeare’s dramatic poetry.

You cannot CARRY empathetic imagination with you until you have trained yourself to treat it with respect, much as you shouldn’t use a donkey to aid your labour if you don’t respect its life and capacity for otherness. But it’s an interactive endeavour – the more you attempt the exercise of imagination, the stronger it becomes – and its strength will have a moral flavour. It will be an act of giving and serving a ‘higher power’ without invoking God, who is one anyway (I would argue) of its products and good only in as far as it isn’t the projection of self-interest. George Eliot thought something like that, and she learned it in translating, from the German, Ludwig Feuerbach’s 1841 The Essence of Christianity, the greatest text of humanist belief ever. To carry is a moral task (not least because it demands nuanced and mature ethical grasp). Let’s hope I can be worthy of it in my remaining years.

With Love

Steven xxxxx