A great novel always takes the trouble to ‘bother me’. The example of Colum McCann (2025) ‘Twist’. In it the narrator talks about his own ‘bother’ about his writing and trying to keep it focused. ‘Tell me about a complicated man, how he wandered and was lost. The story would drift away from repair, which was the theme I thought I wanted. My own odyssey was caught up in itself’. Reparation is a task that would not be taken up unless we believed not only that the past can be retrievable but can be changed, but the end of the first section of Chapter 1 of this novel states: ‘The past is retrievable, yes, but it most certainly cannot be changed’.

‘Tell me about a complicated man, how he wandered and was lost. The story would drift away from repair, which was the theme I thought I wanted. My own odyssey was caught up in itself’.[1] Reparation is a task that would not be taken up unless we believed not only that the past can be retrievable but can be changed, but the end of the first section of Chapter 1 of this novel states: ‘The past is retrievable, yes, but it most certainly cannot be changed’.

It seems self-evident that the past cannot be changed, I suppose, and yet most human endeavour presupposes that it can because we can persuade others to see it differently, and in these acts of re-interpretation change it in some way that changes fundamentally its relation to both present and future time. Reparation of past misdemeanour (ours or those of others, is a task with a complex history itself – in the world as conceived by different approaches to it: theological (where the task of redeemers is clearly to rescue the world from past error – even to see this error as a function of grace – or Providence at least – itself). Witness the opening of Paradise Lost.

OF Mans First Disobedience, and the Fruit Of that Forbidden Tree, whose mortal tast Brought Death into the World, and all our woe, With loss of Eden, till one greater Man Restore us, and regain the blissful Seat, Sing Heav'nly Muse, … That to the highth of this great Argument I may assert Eternal Providence, And justifie the wayes of God to men.

Issues of restorative justice are applied to the healing of the harms suffered by victims and perpetrators of crime, by rewriting them from both perspectives. Reparation in Kleinian psychodynamics is a set of acts of creative contrition (a phrase used by the narrator in Twist to his publisher) by which a child accepts that their negative impulses to their parents aren’t based on real historical crimes of the parent but motivated by the paranoid schizoid position of the undeveloped infant. With such realisation schizoid impulses of idealistic love and vengeful hateful retribution against the parent who does not measure up to those ideal demands give way to depressive and guilty realisation that the world is not organised around the child’s selfish desires and that the child must repair the damage done in their past rage. Zanele, for instance, thinking of her childhood in the oppressed shanty townships of Cape Town says: ‘nothing washes away your childhood’.[2]

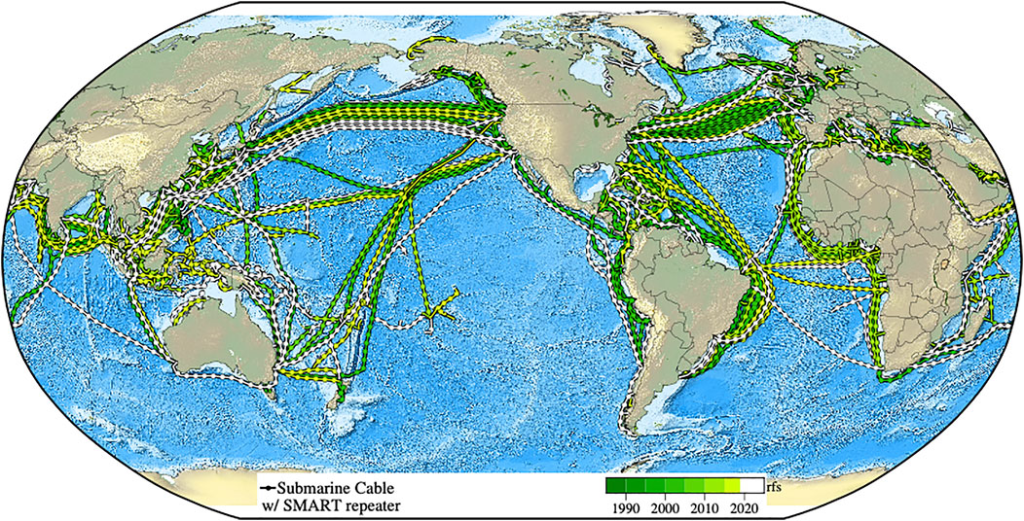

Even societies aim for reparation. The narrator’s publisher, Sachini, reminds him in order to commission from him an article on the necessary work of deep sea internet and cloud cable repair, using the Jewish concept of the repair of, and improvement on, worldly wrongs, Tikkun olam.

The repair he desires has more nuanced objectives still.

She reminded me that I had specifically said that I was interested in idea of repair. Tikkun olam, she called it, a concept I was not familiar with at the time. But repair was certainly was what I craved. [3]

But reparation is a global issue as well. The reparation of the terrible crimes to humanity evident in slavery and commerce in human life, flesh and unpaid labour are still rightly a subject of discussion and retelling of the story of slavery in the light of the imperial West and North having awoken to the guilt of their past action. The issue of South Africa and the doomed object of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission set up just after the fall of Apartheid is even featured in the novel. In the book itself reparation for ecological and environmental destruction is a constant theme.

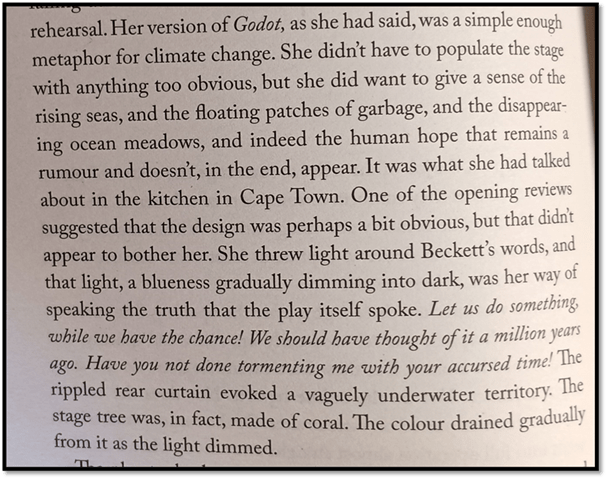

However, even the way we tell stories or allow ourselves to be seen in them can be presumed changeable. Take Prince Hal in Shakespeare’s 1 Henry IV Act 1 Scene 2: 224 . He might as well be a knave he thinks for he can change perceptions of himself when he is Henry V thus: ‘Redeeming Time when men think least I will’. Likewise Zangele as actor-director believes she can present Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, such that it makes amends for the environmental predations on which she believes it actually reflects, that hopes for the future but has no faith in political action to bring it about. Everyone hums to the insistence that nothing can be changed, even the words of Beckett applied to the need for reparation: Have you not done tormenting me with your accursed time![4]

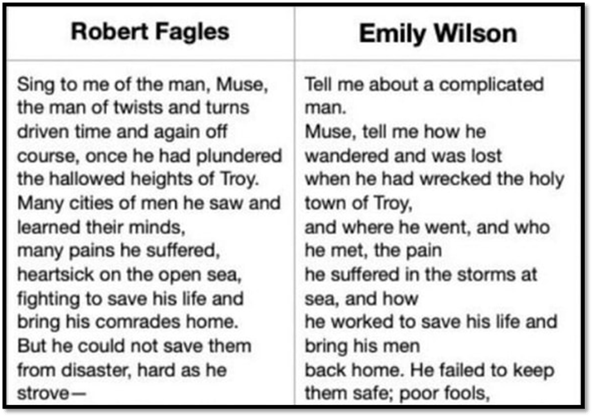

And then what of the past stories retold in Twist – Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, and even Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now and its making as a film out of the former including the story of Martin Sheen’s breakdown in concert with that of his enacted role, and with even more hubris, Homer’s Odyssey. Here is the quotation I began with in my title, with its direct quotation from the most recent and noted translation – one that came with a message to reread the poem as a feminist keen to redeem patriarchy would read it, that of Emily Wilson, missing out only the naming of the object of invocation, the ‘Muse’.

Tell me about a complicated man, how he wandered and was lost. The story would drift away from repair, which was the theme I thought I wanted. My own odyssey was caught up in itself.[5]

Wilson’s translation caused a stir, and was, as male translators rarely are, accused of bias and of being ‘unfaithful’ to Homer and his Greek. In an interview with the Chicago Review of Books she said gutsily:

Translation, like any work of reporting or reading or interpreting or narrating, isn’t like that. I think we should aim not to be “unbiased,” but to be responsible, and that involves being as conscious as possible about our biases and preferences, as well as being informed as possible about the material at hand (which includes our society and the English language, as well as the Greek text). It’s been unsurprising that many people have asked me about how my gender identity (as a cis-gendered woman) affects my translation of the Odyssey. It’s also unsurprising, but highly problematic, that hardly anyone (except me, so far!) seems to ask male classical translators how their gender affects their work. As I show in that piece on Hesiod, unexamined biases can lead to some seriously problematic and questionable choices (such as, in that instance, translating rape as if it were the same as consensual sex).

Translators get away with that kind of thing all the time, because there’s an assumption that male translators don’t need to worry about gender, and that a clunky English style guarantees an “authentic,” “accurate” or “unbiased” translation. It’s not OK and it’s not true. In my work on my translation of the Odyssey, I didn’t want to be in any way untruthful or irresponsible about what the original text is saying or doing. I tried to think, as much as I could, about how my own identities and histories might affect my interestedness in the poem: as a woman and as a gender-aware feminist (which isn’t necessarily implied by the first), and as an immigrant, a mother, a writer/poet, and so on. I thought and wrote a lot on the side about all the many ways I felt the Odyssey mapping onto elements of my own life.[6]

Choosing to quote this new frankly openly feminist version of the poem, aware of its responsibility to future attitudes and to free the past of ‘modern’ misogyny feels to me significant, especially in the context of the book’s fascination not just with the ‘complicated man’ who is putative protagonist, John A. Conway, in the book but his resonance throughout in the actions, words and witness of his South African actor-wife, Zanele. I feel this not least because there are good reasons that McCann was thinking of other translations of this opening, not least one which has association with the terminology of the book’s twisty narrative but its twisty, turny ‘hero’, a man Greek history and literature always presented as of ambiguous morality, Ulysses, that of Robert Fagles! Here is his translation of the opening compared to Wilson’s. The important bit to me is the way ‘a man of ‘twists and turns’ is so much less openly sympathetic with Odysseus, because, after all, most men (I do) like to think their bad behaviour is a reflex of being complicated.

Of course the etymology of the adjective ‘complicated’ as derived from its root verb ‘complicate’ implies twists and turns, but without the obvious implication of human inconsistency, not only caused by external agency, such as live currents in the sea, but also by twisty, turny traits in character. Whether Conway is ‘complicated’ or just a ‘man of twists and turns’, which does not beg a causal explanation, is itself an issue in the book.

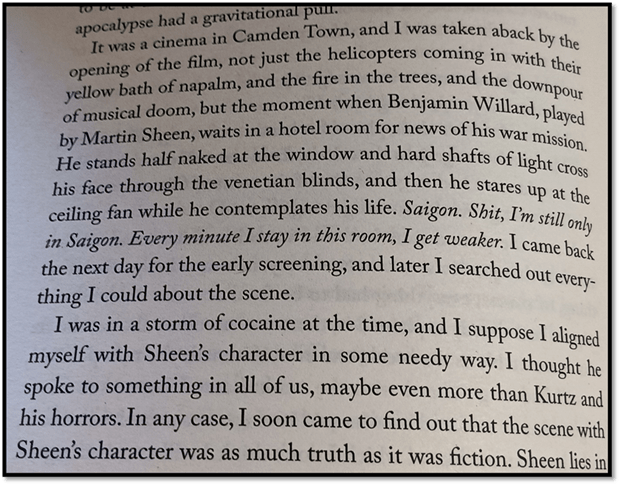

But the source of complication, and indeed of ‘twists and turns’ even in narrative methodology, applies to the narrator too, as complex, and modelled on that of the narrator of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and the complementary role, played by Martin Sheen as Benjamin Willard, in Apocalypse Now.

This gets beautifully interwoven in this tale’s narrative and the shards of each narrator’s life as an addict:[7]

The idea of ‘twists and turns’ however goes further than the exploration of needy complicated men and the narratives they spin, together with obvious silences within them, it is implicit in the need to emphasise ‘the theme of repair’. That is because everyone is repairing all of the time. Some ‘philosophers’ see this as a beautiful thing about the world – in its resilience to permanent direction by something that might be better. See for instance Elzabeth A. Spelman:

To repair is to acknowledge and respond to the fracturability of the world in which we live in a very particular way—not by simply throwing our hands up in despair at the damage, or otherwise accepting without question that there is no possibility of or point in trying to put the pieces back together, but by employing skills of mind, hand, and heart to recapture an earlier moment in the history of an object or a relationship in order to allow it to keep resisting.[8]

No nuance here about ‘fracturability’: breakage is always a bad thing to Spelman on this passage’s evidence, even when the need for repair involves breaking some rather nasty current developments – like new means for dumping waste at sea (and at a cost to ecological integrity) or the ambiguous benefits of internet communication, some of which sustain systems of evil or its potential to greater global effectiveness. After a life spent in repairing the cables that sustain the internet, Conway falls into despair at the value of that he is repairing; a world whose communications and connections through technology are at best (and least harmful like other uses) expressed as continuing and endless ‘tedium’:

Things broke, he went to sea, he attempted the repair, and like the rest of us, he didn’t quite know what to make of it. He had told me he was not responsible for what happened on the internet and all that truly concerned him was the actual cable. But that gulf had been blurred. He had attempted to fix something. The hopeless, eternal question: to what end?[9]

That ‘hopeless, eternal question: to what end?’, does not apply only to agents of repair. Once Conway ‘twists and turns’ into a committed agent in the destruction of a world using connection for evil ends, he finds the same question arising perhaps. We aren’t told but the narrator certainly raises that question to Zanele. If you think things might be made better by breaking things, what then? Except that, you might be doing it to show that bad things get repaired more effectively than means towards good ends, as the narrator finds in conversation at the end of the book with Zanele:

“But what was the point if it was all going to be repaired?”

“ Maybe that was exactly his point.” [10]

There is nothing simple about the ‘theme of repair’ then and there are reasons why any narrator might prefer their story to ‘drift away’ from that theme, or apparently so. One of my favourite sentences in the book is about how the status quo sustained in the interests of the ‘few’ not the ‘many’ explains away the protest made by Conway after his death in action under the sea. To realise the bitterness that underlies the sentence I quote next, you must think of the absence of effect of McCann’s great novel on Palestine, Apeirogon, a novel of repair par excellence (see my blog on it at this link: I adore this book but it was followed by a long period of silence in McCann’s career). No one tries to understand Conway (feel the sadness in that phrase ‘of course’:

It was all attributed, of course, to terrorism. The bombers were clothed in the inevitable language of kaffiyehs.[11]

In truth nothing about the language of kaffiyehs is inevitable or about terrorism. In an anxious attempt to repair I lay bare my own soul here.

There was only one bomber – terrorism hardly covers a description of his purpose, except for Western governments who are more alarmed at threats to property than life, at least if the lives are Palestinian, aimed at no body, only institutional structures.

From left: Colum McCann, Bassam Aramin, a Palestinian, and Rami Elhanan, an Israeli Jew (Photo by Toby Tabachnick) The latter two real people here are McCann’s main ‘characters’ in the novel and both seek to end Arab-Israeli conflict. From ‘The Pittsbugh Jewish Chronicle’. Available at: https://jewishchronicle.timesofisrael.com/israeli-palestinian-conflict-explored-in-colum-mccanns-new-novel/

”But repair was certainly was what I craved’, says the narrator. He desires a narrative structure ture that has coherence or wholeness, and perhaps less .easy communications and twisted narrative threads or cables. Hoevet, he also wants what both Willard in Apocalypse Now, and Martin Sheen, who plays him, want: reparation from the effects of the deeper causes of his impoverished relationships and alcoholism. Repair is in part that thing E. M. Forster sought when he and his novels taught us – whether we be in Passage to India or Howard’s End and all other places and circumstances – to ‘ONLY CONNECT’. The narrator puts it thus:

I had a feeling that I had exhausted myself, and that if I was ever to write again, I would have to out into tne world. What I needed was a story about connection, about grace, about repair. [12]

To underline the irony , the next section of the chapter immediately below this begins: ‘I had no interest in cables’, for connection by cable is forever in this book the symbolic icon of non-communication, or communication that does not ‘work’, as in that involved in the breakdown of Conway’s relationship to Zanele.

Relationships like other connections cannot be mended after breakage very easily. Neither can stories [especially nostos stories about tne return to an original ‘home’ of some kind like the Odyssey] stay connected and intact that easily when their agents ate ‘broken’ too, however much these agents desire or ‘want‘ to be whole:

The best way to experience home is to lose it for a while … You can yearn to return to it. It is a kind of wounding. …

We go to sea, too, because there are rules out there to obey. … A cable is broken. … You find the cable, lift it up, splice it, put new cable in. … Go home with the story intact.

That’s not what happened, but that’s what you want. [13]

When Conway finds a particularly hidden cable, he days, ‘ There she is’, as if, or at least the narrator thinks this, he has found his connection back to Zanele, broken by time, distance and misunderstanding.: ‘ a rope of time and distance’ [14] And the same goes for the desire to tell stories about the ‘theme of repair’: ‘If this were a fiction, I would scold myself for telling too much, and at the wrong time, and in the wrong order. … , I would cap my pen and begin again’. [15]

This failure to tell a straight story, intact in all its connections, is precisely why the fragmented and fragmenting narrator of this broken story of multiple broken things finds his own ‘odyssey caught up in itself’, and is in ‘it’s own turbulent flux’. [16]

Twist is more though than a clever meta-story [a story about the process of storytelling], it is an urgent document about tne potential deep links between tne shaping of postmodern alienated psyches, the ecological crisis and the rampant unstoppability of modern capitalism and its hunger for growth at the cost of everything we once called life-enhancing: beauty, truth and meaning. The novel starts on its first sentence with all things in crisis: ‘We are all shards in the smash-up’, in a world where paywalls are constructed to guard what turn out to be ‘piles of shredded facts’ [17]

Moreover, if ‘all stories are love stories’ or ought to be what we call love in all relationships, it seems lost along the way. This is even so in father-son relationships, and, yet again (repeating the very terms of the novel’s first sentence, ‘we are all shards in the smash-up’. [18]

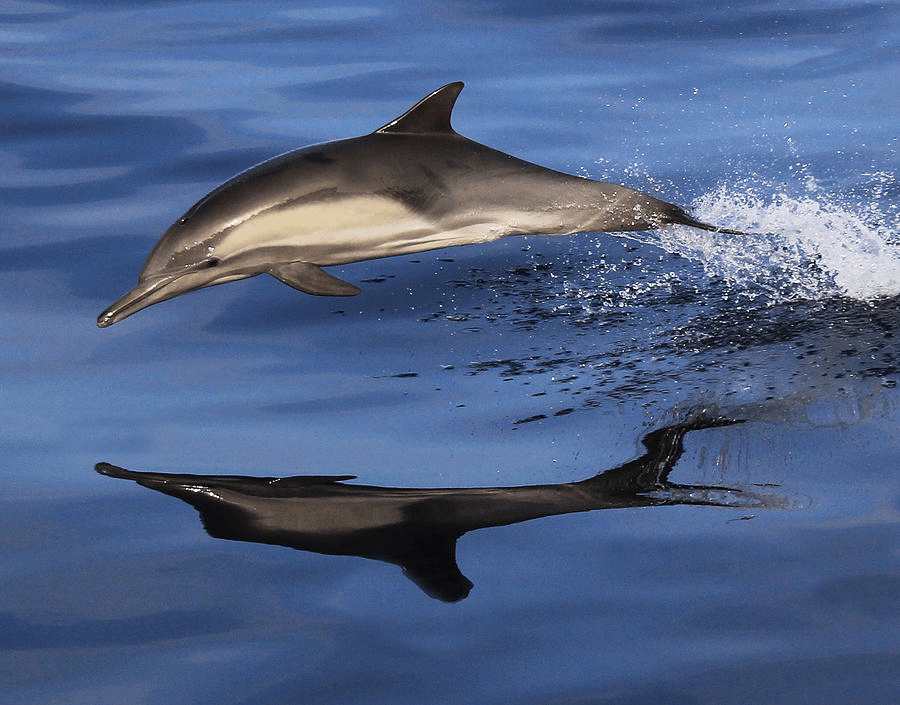

There is so much I want to say about this novel – and something about how deep seas ape the mind, so much so that a ‘moment’ (of time) can be said to have ‘dolphined up‘, is one of them [19]

But that’s enough – maybe too much – from me for now.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx

[1] Colum McCann (2025: 157f) Twist London, Bloomsbury Publishing

[2] Ibid: 229

[3] ibid: 6

[4] Ibid: 118

[5] ibid: 157f

[6] Amy Brady (2018) ‘Interviews: How Emily Wilson Translated ‘The Odyssey’ in Chicago Review of Books (January 16, 2018) available at: https://chireviewofbooks.com/2018/01/16/how-emily-wilson-translated-the-odyssey/

[7] Colum McCann op.cit: 142

[8] Elizabeth V. Spelman (2002: 5f.) Repair: The impulse to restore in a fragile world Boston: Beacon Press.

[9] Colum McCann op.cit: 140

[10] Ibid: 234

[11] Ibid: 215

[12] ibid: 5

[13] ibid: 71

[14] ibid: 113

[15] ibid: 117

[16] ibid: 158

[17] ibid: 3f.

[18] ibid: 113

[19] ibid: 111. Real dolphins appear ibid: 145.