The illustration – by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff – is from the Harvard Gazette article cited below, but to give up a book because it makes you uncomfortable may not be to ‘bin’ it but just re-shelve it in your mind (source: https://content.news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2024/10/when-to-quit-a-book/ ). After all the bin in the illustration has a l;ong shadow – not unlike guilt itself

I rarely if ever give up on reading a book when it is a challenge – I think the last thing was James Joyces’s Finnegan’s Wake and then it was at university. Nevertheless I have never taken up the book again. There remains in me a kind of level of residual guilt, akin to the fact that I am rather snooty about people who say the same about that wonderful novel by the same writer, Ulysses, though readers who say so are legion. Reading is a complicated activity that we learn together with lots of myths that both sustain and mystify it, where success is akin to a kind of necessity that has as much to do with feeling not up to a challenge as to seeking completion in all the things we do. That this is the case seemed borne out by a piece I came across online from The Harvard Gazette from 2024, a kind of boffins’ talking-point magazine. The illustration above comes from it. It’s called ‘When to quit a book: Some give up without guilt while others insist going cover to cover. Harvard readers share their criteria’ and is by Liz Mineo. [1] It begins:

On the matter of whether it’s acceptable to stop reading a book before its end, there are two schools of thought: one that says we must finish what we started, and one that declares that life is too short for books we don’t enjoy.

The Gazette asked librarians, a classics professor, a literature scholar, and a lecturer in English for their views on a subject that triggers fiery debates among book lovers. Although all seven readers interviewed for this story fall on the “life is too short” side of the debate, they differ on when it’s OK to give up without guilt.

The contributions are mainly from professional academic librarians who know that to abandon a book does not mean ‘binning’ it, but returning it to shelves to gather dust and await a ‘fit audience’ conscious that that qualitative fitness in an audience implies a quantitative limitation: ‘though few’ in Milton’s formulation. And as I quote that bit of Paradise Lost, Book 7 ,from memory, I turn to check it out, to find that it is in Milton probably that the attitude to reading that haunts people like me may have derived. Here’s the context – as Milton invokes his Muse Urania and possibly aware that his great poem will be in the future a thing more often referred to than read through in its entirety. He thinks that just, he claims, as he is only half-way through the arduousness of his writing:

Half yet remaines unsung, but narrower bound

Within the visible Diurnal Spheare;

Standing on Earth, not rapt above the Pole,

More safe I Sing with mortal voice, unchang'd

To hoarce or mute, though fall'n on evil dayes,

On evil dayes though fall'n, and evil tongues;

In darkness, and with dangers compast round,

And solitude; yet not alone, while thou

Visit'st my slumbers Nightly, or when Morn

Purples the East: still govern thou my Song,

Urania, and fit audience find, though few.

But drive farr off the barbarous dissonance

Of Bacchus and his revellers, the Race

Of that wilde Rout that tore the Thracian Bard

In Rhodope, where Woods and Rocks had Eares

To rapture, till the savage clamor dround

Both Harp and Voice; nor could the Muse defend

Her Son.

‘Ay, there’s the rub’. If you, as a reader are not part of the ‘fit audience’, the alternative is to see yourself not as the answer to the question ‘what constitutes a good read’ but the problem./ It may not be all our fault, Milton hints, we are in ‘evil dayes’ in a culture of ‘evil tongues’, too ready to pour treacherous opinion on the great writers of the day struggling with our shallowness. But, we have to face it, to not to be able to hear he harmonies and beauties of Orpheus , the Thracian bard’, is to be akin to the Maenads (or Bacchae), who in their drunken (and feminine – since Milton had no great appreciation of female taste) self-pleasuring ignorance (‘barbarous dissonance’), ‘tore’ the body of Orpheus into fragments, and which, in Classical Greece could be represented by Amazons – those threats to patriarchy, as Orpheus – much more fay than they- ironically presses himself against the very realistically represented phallus of a herm behind him (in some versions the Bacchae are said to turn against him because, after the loss of Eurydice, he had turned to the sole love of men):

The Death of Orpheus, detail from a silver kantharos, 420–410 BC, part of the Vassil Bojkov collection, Sofia, Bulgaria by Gorgonchica – (CC BY-SA 4.0: File:The Death of Orpheus.jpg) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orpheus#/media/File:The_Death_of_Orpheus.jpg

Who, brought up out of a working-class home, the first in my family to be educated beyond the age of 14, wanted to be part of ‘barbarous dissonance’, deaf to the beauty and harmony of the art of the lyre, voice or brush? Better to be like Milton, and though ‘Half yet remaines’ unread of a challenging book we realise that whether we finish it or not is a judgement on us – one almost proceeding from above us in some celestial sphere. But even representatives of the Harvard English Department somewhat change their tumne these ‘evil dayes’. Witness this from the continuing article in The Harvard Gazette:

Worry less about reading from cover to cover and focus instead on the experience, said Sophia J. Mao, lecturer on English at the Department of English.

“Reading, especially today, is never a solitary activity but comes alive in the classroom, on BookTok, at events in public libraries, bookstores, and community spaces,” said Mao. “As a literary scholar and a teacher, I may guide others toward what makes a specific book notable, but I also want to know what other works people are drawn to and why. I’ll never be tired of hearing from others what they find beautiful and moving. It’s what makes reading a pleasure and a challenge to my own perspective on whether a book is ‘worth’ it.”

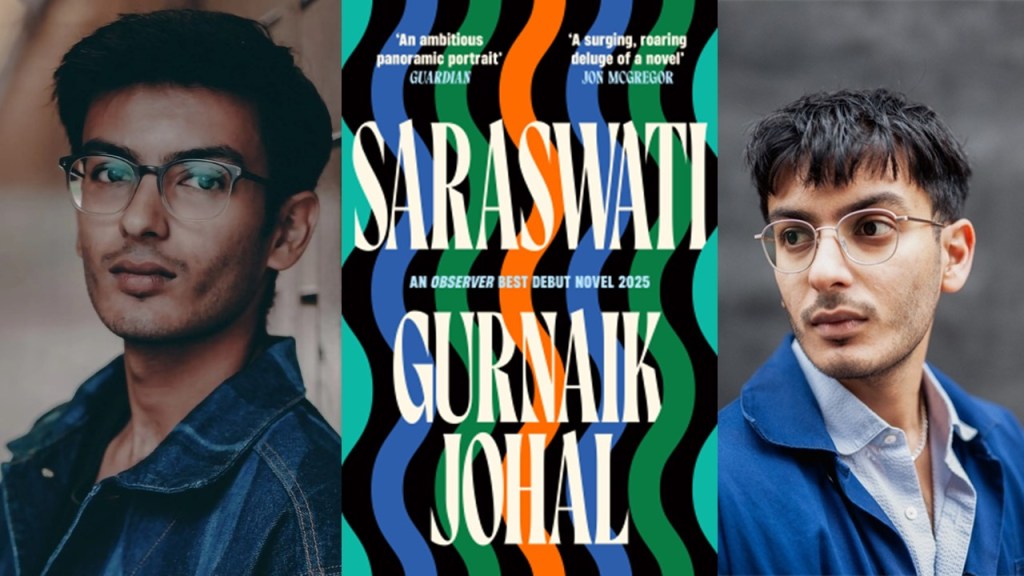

It isn’t a clear recommendation here that its okay to abandon a book but it so changes the emphasis that we no longer worry about whether incompletion of a challenge disqualifies us from an opinion of the experience we have had. So now for my confession. Fired by reviews and opinions – winning debut books awards from The Observer and Waterstones – I ordered myself a copy of Saraswati bu Gurnak Johal, and booked a ticket to see the author at a reading event at Northern Stage in Newcastle, and yet within 70 pages from the end, lying in bed – frustrated and out of sorts mentally, unable to make the pace in change of changes between the many focal people, spaces and times that this novel requires you leap between, I just threw my bookmark to the side of the bed – a gesture that meant that if I read this again it must be from the start – and pouted with exhausted and challenged defeat. In truth I was uncomfortable – with the book, with my inability to cope with what I believed it to demand of me and more – and could only ‘use the strategy‘ of symbolically throwing the book aside to decrease the discomfort I felt.

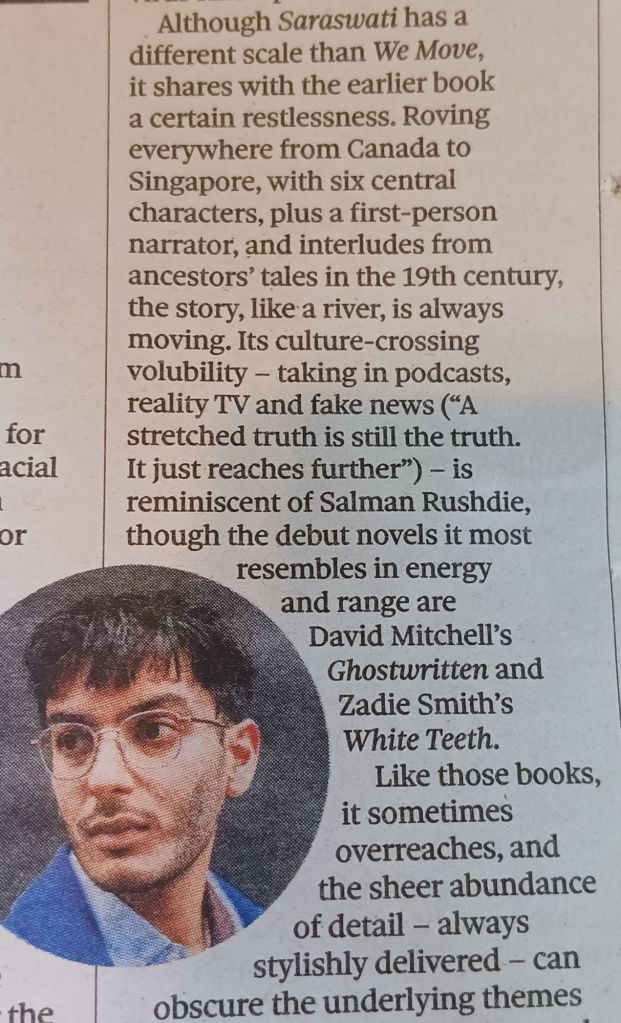

Yet seeing this prompt has made me pick the book up again, read a review (John Self in The Observer) and consider the behavioural issues again. [2] It is likely that I will go and listen to Johal speak in Newcastle now, more so that, some time passed, I will start the book again, for it had a fascination that kept me to it. I noticed that Self sort of gives some reasons why some readers will despair with this long book – see this section of his review, which starts with a reference to Johal’s first publication, a set of short stories:

Very rarely have I found a review so helpful. It was helpful because it diagnosed my problem with the novel. I recognised my discomfort as a kind of resistance to the novel’s demands that I keep my nervous response to the novel on the edge of discomfort, and sometimes way over the edge – not only in its multiplicity of foci but its ‘certain restlessness’ of feel. The analogies with early David Mitchell – referencing the latter’s debut – and Salman Rushdie, whose latest books now continually provoke me to incompletion (Quichotte for one) I can’t mend but whose Midnight’s Children (1981), Shame (1983), The Moor’s Last Sigh (1995), The Ground Beneath Her Feet (1999) and Shalimar the Clown (2005) are as near to a new kind of literary perfection, that the term ‘magical realism’ barely covers, as you might find. With Zadie Smith I see no analogy (hers is a perfection in a classic mode).

Moreover, two elements that Self diagnoses ought to have kept me going and probably will in a future reading:

- The link between (a) the theme of water (rivers, seas, ice blocks and their knit from diverse mythologies of the divine to their ecological and socio-political import (from being thieves of sustainable agriculture to their representation of a need being privatised by profit incentive) to (b) the process features of the novels pace and motion – in floods, flows and surges that you just have to cope with as a reader. and;

- The cavalier ‘boundary-crossing’ of the novel between different spaces and times – that at some points even disrupt a sentence. This is not only about the shift of the novel from a comfortable fable (popular enough in South East Asian diaspora literature) of a nostos involving a re-evaluation of both homes that the mental-or-physical-traveller in space-time crosses between (not least in Salman Rushdie) to something where no foot can rest on solid ground. It means that the experience itself of characters – even the characters themselves – are liminal (on the edge of definition and ability to shape-shift).

And these elements cross. The central feature of the novel. Saraswati, is a river (or is it – maybe a fiction of myth or politics?), a goddess and a complex theme in which the meaning of art as expression and a medium of transfusion can even resolve into the very nature of speech used in communication. It is also a book, a play and a film.

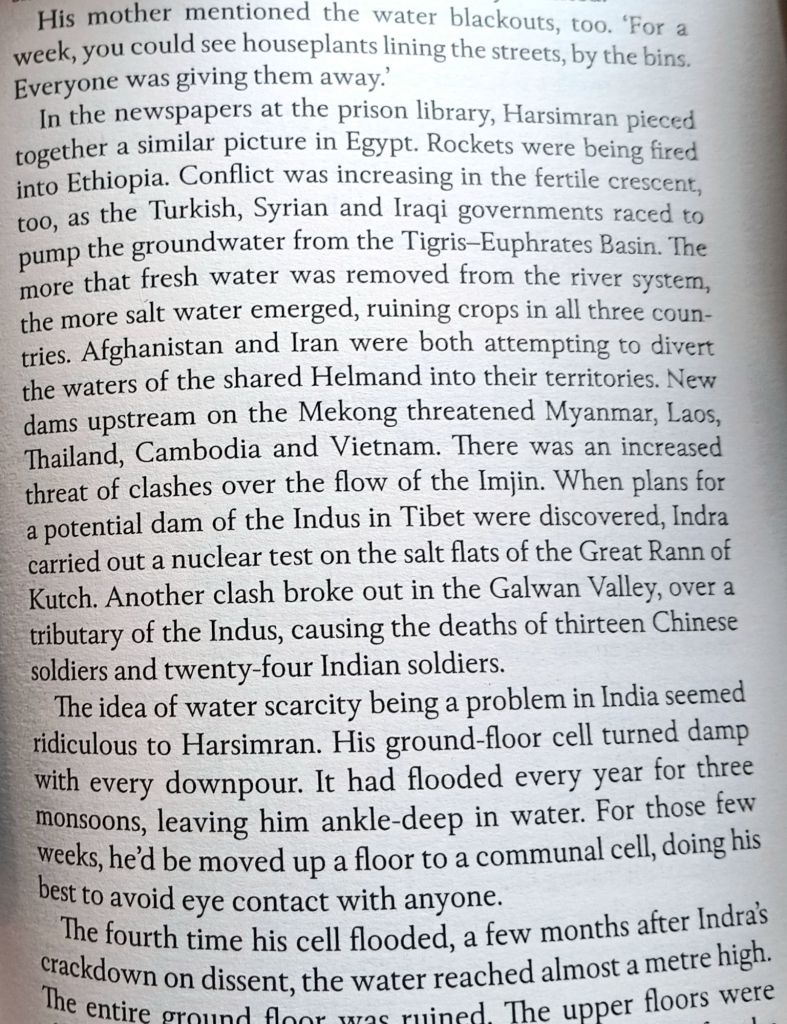

Moreover, its origins and destination are found (physically, by mental research or the from the source of some trans-spatial connection in spaces that cross time and space boundaries). It would be easy if these were just national boundaries – but they are not, as the very nature of India as a nation is not merely a fact of history and geography. This book even returns to the origin of Indo-European languages and the myths of the Aryan ‘race’, at the basis of all national-imperialist motives and again raising its end in Narendra Modi’s form of national imperialism based on old struggles with West and East. [3]

It would be remiss of an art with this kind of ambition to plump for a comfortable form in its structure, links and even in some of its sentence formations in specific transitional chapters. Yet transitional or not, these sentences never lack motion – before you stop to puzzle over them (as you do in Finnegan’s Wake) you are already been pushed forward by the current that moves them, as if from beneath. In the motion the grasp of character, relationships, the politics of water, the nature of national and internal power blocs all meld in restlessness. Here is an easy piece of that kind of focal shifting. You can’t resolve it into plot, character development or politics alone, and at other times the foci become more diverse – taking on the nature of language, art and communion. [4]

Make no mistake I will be back to this novel. Not because I have resolved the problem of why I get guilty abandoning a novel but because I know now that the discomfort of restlessness is nearer to the main theme of our age, as Bruce Chatwin also believed and which made him torn between an interest in nomads and unhealthy-stickers to their own place and time. This is a novel that ought to challenge and how much better to fail with it at first than to think you deserve to be comfortable in a world where to be comfortable is to be complacent of evil. And Milton, after all, was right about the Restoration of Monarchy in 1660 being being a rerun of the Fall of Man, even in Cavalier literature, aimed at making the rich and powerful feel ‘anything goes’.

With all my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxx

________________________________________

[1] Liz Mineo (2024) ‘When to quit a book: Some give up without guilt while others insist going cover to cover. Harvard readers share their criteria’ In The Harvard Gazette (October 17, 2024) available at: https://content.news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2024/10/when-to-quit-a-book/

[2] John Self (2025: 41) ‘Water flowing underground’ in The Observer [29.06.2025]: 41.

[3] See Gurnak Johal (2025: 296 etc.) Saraswati London, Serpent’s Tail

[4] ibid: 287

Interesting!

LikeLike