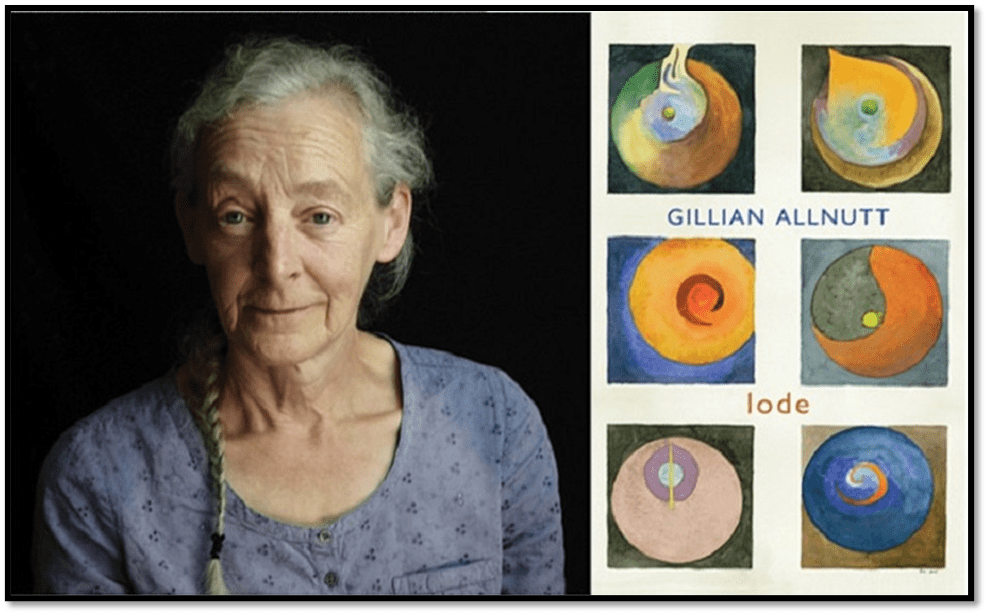

I bought Lode from the Left bookshop in Durham where Gillian Allnut herself works as a volunteer, and I read it through for the first time last night before attempting to ignore the heat and sleep. What buzzed through my mind together with the gorgeous complex rhythmic adventures and associations with recall from past great literary art felt deep and viscerally in being re-read, was the sentence: ‘This is what poetry is when it is not merely verse’. That’s a big feeling for me as an amateur versifier rather than a poet.

Since I baulk at expressing my gratitude because of the danger of seeming false, insincere, and unauthentic, I can only do it indirectly by choosing one poem from the volume that is precisely and primarily an act of gratitude but also a masterclass in how to voice such gratitude. Here it is: The Golden Saxifrage.

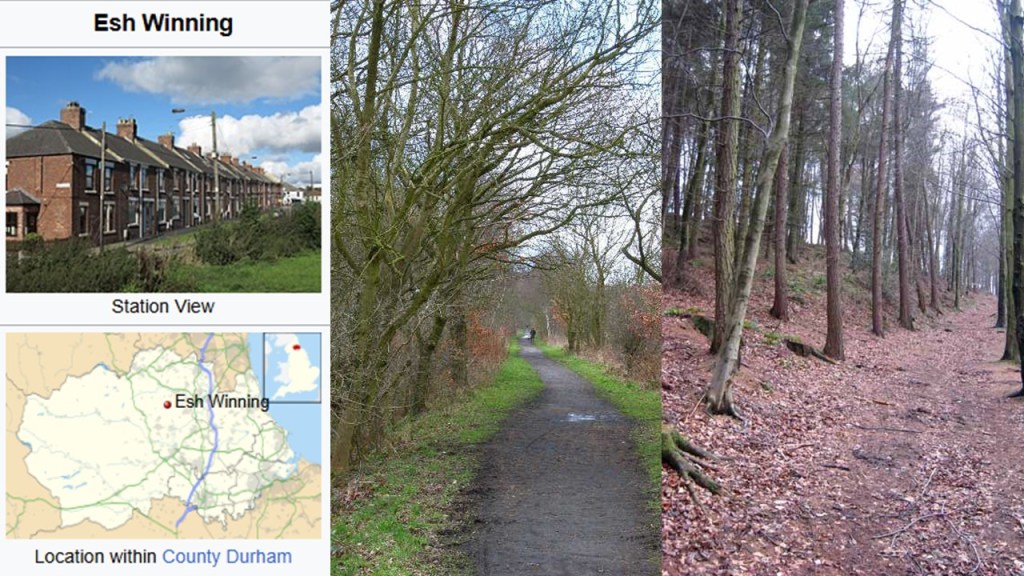

The poem is addressed to the object of the poet’s gratitude, presumably ‘Marney Harris’. That person is someone whose every act as described in the poem (for we cannot know her unless we too are Esh Winning residents – Allnut’s current home village – over the hill from the dale I live in) seems so full of grace that the benefits of those acts give quality to life. The qualities given are like that we sometimes associate with those of religious faith in the face of acceptance of our own mortality. It is a lasting, even a ‘lingering’, quietude.

The photographs of the disused railway path in Deerness Valley running past Esh and that of the path through Ragpath Wood (familiarwalks for me and both referred to in poems in ‘Lode’) are by Oliver Dixon [see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Esh_Winning]

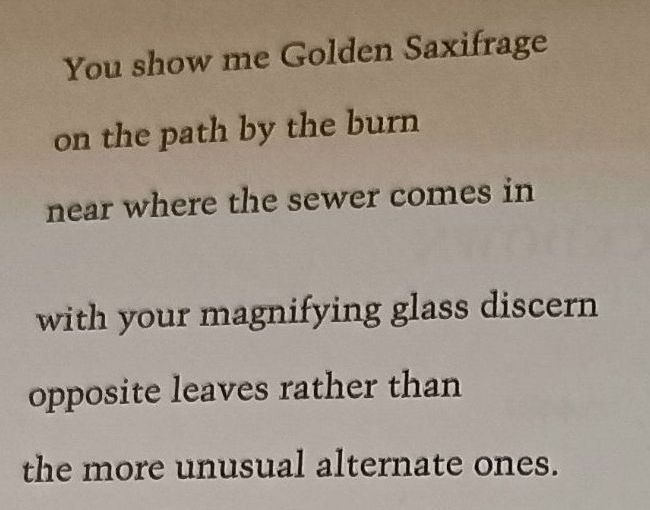

Why focus on the Golden Saxifrage but that it is an emblem, looked at closely, of the beauty of diversity of each token of its kind within one type of life. A token, by the way, is a term philosophers used to distinguish from a category of a thing, a particular instance of that same thing. Whereas the type is the category like that of saxifrage plants in general, a token is one particular saxifrage plant looked at closely. Only when we look closely do we see the difference by virtue of which and other differences the token is distinguished from the type,of which one instance of such differences might be that is this is a saxifrage plant with alternate rather than opposite leaves.

The lyricist sings of being shown how to ‘discern’ the alternate-leaved and the more unusual opposite leaved tokens of the saxifrage type. It is not this knowledge that matters to the lyricist, however, but the act of skilled discernment she is taught, itself carrying with it an appreciation of the principles that make diversity not uniformity the true measure of beauty.

The act of both showing and the act of educated and skilled discernment (‘with your magnifying glass) are both to be valued but not least because of the agency of ‘you’ (particularly ‘you’) in that act of giving a beautiful gift. When ideally I give thanks for and to someone I want them to feel that I see what is beatifull and individual in their action of giving – individual in that it comes from the paticularly defining qualities of your kindness addressed to the particular need of me in particular. In such acts, as Martin Buber might have put it, ‘thou’ speaks to me in the particularity of my ‘I-ness’.

For if people fall into types, thanks must be directed not to the type of humanity each person falls into, but to and from two examples of the specific tokens of human persons. I have to be careful in this instance that the word ‘token’ is distinguished from the descriptor ‘tokenistic’, for gratitude that is described by the later word is precisely the opposite of the gratitude that persons feel to involve them at the deepest core of their individual being.

We need to understand the last point in order to understand the beautiful use of the word ‘kindness’ in it. The word has an etymological history, told in etymonline.com as interestingly as usual:

kindness (n.): c. 1300, “courtesy, noble deeds,” from kind (adj.) + -ness. Meanings “kind deeds; kind feelings; quality or habit of being kind” are from late 14c. Old English kyndnes meant “nation,” also “produce, an increase.”

kind(adj.) : “friendly, deliberately doing good to others,” Middle English kinde, from Old English (ge)cynde “natural, native, innate,” originally “with the feeling of relatives for each other,” from Proto-Germanic *kundi- “natural, native,” from *kunjam “family” (see kin), with collective or generalizing prefix *ga- and abstract suffix *-iz. The word rarely appeared in Old English without the prefix, but Old English also had it as a word-forming element -cund “born of, of a particular nature” (see kind (n.)). Sense development probably is from “with natural feelings,” to “well-disposed” (c. 1300), “benign, compassionate, loving, full of tenderness” (c. 1300).

I think the point is clear: the word is derived from the same root as ‘kin’ but can be used both with a wider meaning to speak of the relationships ex[pected between persons of the same category or ‘kind’, like members of the same nation or social group, although latterly taking on meanings associated with the quality of the acts that are called ‘kind acts’ or examples of ‘kindness’. These meanings were shifting a lot in the sixteenth and seventeenth century and explain the word play in Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 2, lines 66 – 75.

But now, my cousin Hamlet and my son—

HAMLET, aside

A little more than kin and less than kind.

KING

How is it that the clouds still hang on you?

HAMLET

Not so, my lord; I am too much in the sun.

QUEEN

Good Hamlet, cast thy nighted color off,

And let thine eye look like a friend on Denmark.

Do not forever with thy vailèd lids

Seek for thy noble father in the dust.

Thou know’st ’tis common; all that lives must die,

Passing through nature to eternity.

It is so quick and witty a language – that of the punning court – playing on the variable meanings of words, shifts of meaning in them, and even homophones. An example of the latter is young Hamlet taking up the cloudy weather imagery of Claudius (his Uncle and now King following the death of his father, Old Hamlet) in order to disclaim any relation of ‘son-ship’ between himself and a man who wants to speak to him as a father: ‘I am too much in the sun’. But all of that is the same kind of word play as the more relevant line (line 67): ‘A little more than kin and less than kind’. The line depends on distinguishing kind as a category describing members of the same kin or even ‘kind’ (the Royal Family of Denmark). Hamlet wants Claudius to know he thinks of him with very little gentle and tender feelings than he thinks of him as a father, and that he knows Claudius’ motives towards him are less than ‘kind’ too. These are the contexts I find animated in Allnut’s wondrous poem

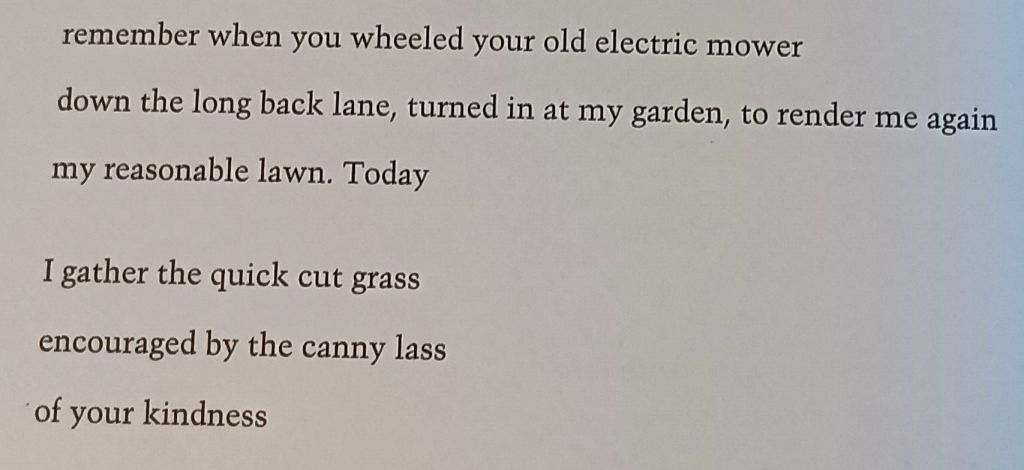

When some people thought of you, as an older person, in tne period of Covid they kindly did things for you, things for which you are genuinely grateful, perhaps like mowing your lawn when you found that difficult. Genuinely kind acts occurred but nevertheless it was a kind of kindness based on abstract principle – like ‘assisting older people in need’ – where the relation of I and Thou is secondary or non-existent in the act. But look at the act described in this poem:

There it is, the kind act done for an older lady by a fitter and perhaps younger one. The act is described with formality (in ‘render me again’ and the rather strained use of the adjective ‘reasonable’ in particular) which is a form of address implying a highly formal linguistic register. However. the rhythmic feel of the lines is elsewhere, and especially in the next stanza, very chatty and makes use of Nordic origin dialect forms (‘canny lass‘), exploiting the sing song effect of rhyme and half-rhyme (‘grass’, ‘lass’, -ness’). The kindness is thence in the last line allowed to be and be expressed in familiar terms of people, who despite differences of kind – class, origin, age and so on – see themselves but not only ‘more than kind’ in so particularised a way that they express a kind of kindness of category.

Some of this expresses, I think (though this is a guess – I do not know the poet), the kind of kinship of County Durham villages – particularly of Esh Winning, the place par excellence in Lode. Some of it depends on knowledge of the local area, for instance I know the ‘path by the burn / near where the sewer comes in’, although I did not know as a true Esh resident would that it was a notorious site for water pollutants about which locals got activated – the burn is Priest Burn.

Of course, this is a poem about ageing and feelings of mortality – but particularly of how ‘quietude’ might characterise both – which has:

lingered and will linger in me as the sun and I

go down

Quietude of course is not the only possible response, as you will see in the poem Triste, with it complex ambivalent memories of Keats embedded in it. That The Golden Saxifrage was a poem from lockdown during the Covid pandemic matters too in this respect as the poet finds, and is grateful for the news and outlet, from the same friend, of:

... an online

Literature Festival from the living room

of the world. ...

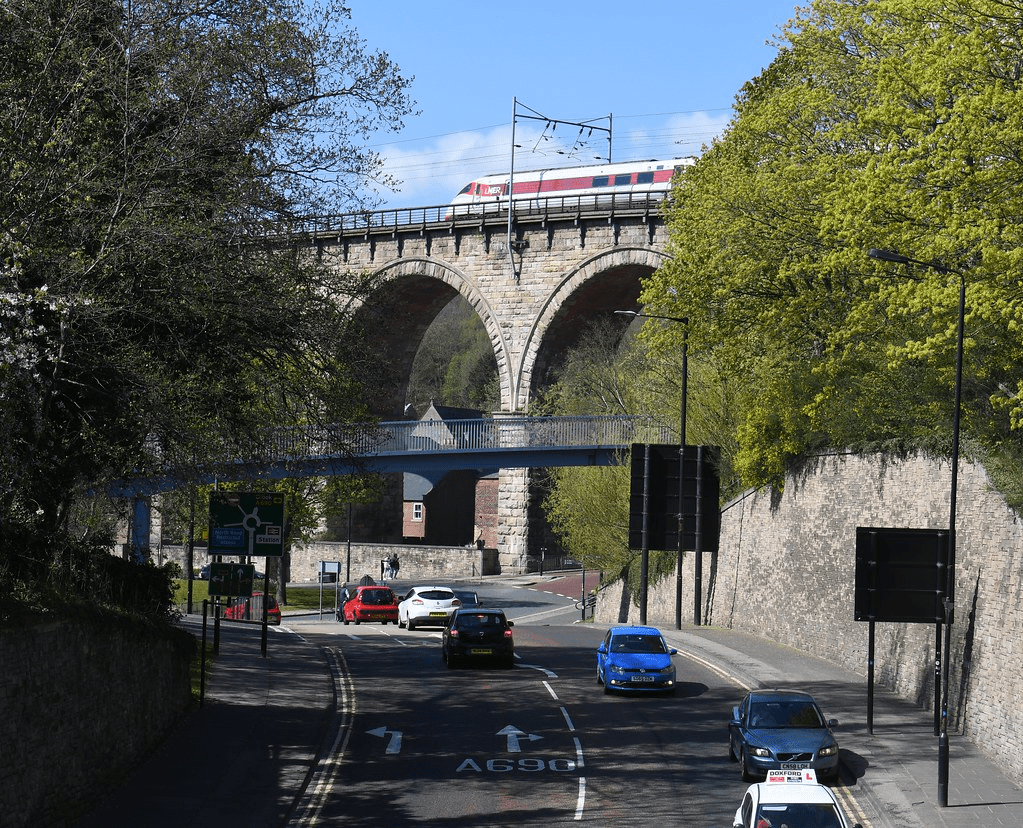

Another kind of kith-and-kin-making is hallowed here – important for this poet who plays games even with E.M. Forster’s favourite phrase: ‘Only connect’, wondering if that means we are beholden as a people to a London and North East Railway (LNER), Azuma (a train name – from the Japanese for ‘East’) that sounds much like the communication tool of lockdown, Zoom. We hear it passing over the railway viaduct at Durham City Station.

Only connect, communicate

courtesy of Zoom -

just as we are, we say, as if we were at home.

....

What did we gain or lose when we listened instead

to the breathing of trains - azuma, azuma -

paused on the viaduct?

A LNER Azuma crossing the viaduct out of Durham Station to the South. Of course I am too literal using this but …..

Read these poems. They haunt me. I may come back to them.

With love to all,

and unspoken gratitude to Gillian Allnut

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxx

Wonderful post 🎸thanks for sharing🎸

LikeLike

Thank you poet ❤️

LikeLike