‘… something between me and the picture felt poised on an edge waiting to happen, the verge of something wild’. [1] This blog is for Joanne, who loves and understands Ali Smith, relating to that author’s republished essay on Munch in book form, ‘So In The Spruce Forest’.

Some people, and Joanne is one of them, just know that there would be no purpose to art except in as much as our seeing of it is also a relationship with that art. Relationship with a thing that is, despite our feelings about it, in fact both inanimate and dead, without anything like pre-existing subjective being or independent spirit when unread, must therefore involve the reality or the imagination of touching, feeling, sensing it, together with which range of things come correlated thoughts, memories, anticipation and emotions, where feeling mediates between sensation and emotion, in order for it to feel to be a living thing. [1 A Note on Milton] Without this function, art is just a thing, an artifact or commodity. Its value is in cash and is set on by the brutal motions of the market alone, although that fact is sometimes concealed in some mystic abstract notion of elite connoiseurship focused, it thinks, on truth, ‘taste’ or beauty.

None of the latter is what drives Ali Smith when she describes art or invents the scenario of a novel. Relationships are nuanced sometimes by the mismatch of what we say and what we intended to mean in them, in exchanges of language, and about them. Our relationships get locked in by words that aren’t quite the right words to describe the meaning but have no alternatives if we are to communicate at all. This is not because language is a thin and poor medium but because it is, when used in and as art or about art, a rich thing with multiple means of understanding it’s basic elements, even the basic building block of words.

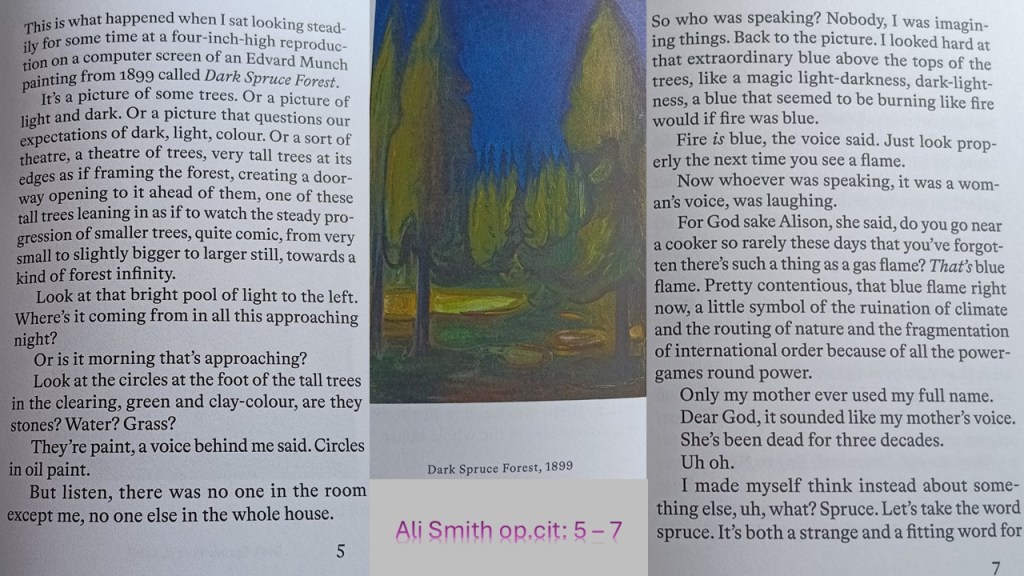

Ali Smith knows this so well that no word they use is left alone to just mean whatever any chance hearer or reader may want it mean, ruling out other readings of their own or of others. Hence, she mays much of the words of the titles of Munch paintings: the word ‘spruce’, for instance, in the painting that gives this work its title. In English, it is not just the name of a fir tree but describes someone attentive to the management of their appearance and its effect on others. Even when we look for the word in Norwegian, from which it is translated [gran], different meanings accumulate around it and are used to enrich what we see in the artwork.

Hence, words don’t get get in the way of descriptions of works of art aimed at showing exactly what we see but are used as tools to see it more richly. In doing so, Smith insists that we need more than one voice speaking in more than one kind of discourse, in order to see art thus, even if we imaginatively create the locus of other voices within ourself. Doing the latter is Ali Smith’s way as a novelist but also as a commentator on things constructed by humans. The key voice in dialogue with her comes from memories of her mother, now no longer living, resurrected within herself but as having learned too what she knows (let me know if the collage is unreadable and I’ll change to separate pictures for each page).

As in relationships, looking is never enough. Unless something happens when yo are looking the relationship fails and thus with art. For Ali, what ‘happened’ is that when she tried to describe what she saw, she found so many options and / or alternatives for what she might be seeing, even as she sought the appropriate words, her own self-consciousness dramatised her self-dissatisfaction. At first she just talks to herself, but allowing that talking to express conflicting views. But finally, almost involuntarily, that voice gets cast in the role of her mother (obviously a source of contradiction in her past and model for it). The voice is ‘behind me’ (in space or time or both), and is embodied by being cast in the role Ali recognizes as her mother, even though she is certain that ‘there was no one in the room except me’. The voice reprimands her when she thinks more simply than she knows from experience – in falling, for instance, into stereotyped ideas about the colour of ‘fire’. The voice even falls into calling Ali ‘Alison’, the only person who did so in the past being her mother (it was much the same with me – only Mum ever called me Steven (and then in critique or dudgeon, and thus I became Steve for most of my life until my seventies).

Ali tries to shut out the voice but we know she will never succeed because relationships are modelled in the memorial of the senses, cognitively and emotionally in indelible patterns learnt early in life. They are indelible even though the characters in these models are as capable of change as living others, provided they are willing to learn from each other. Exasperated with her mother’s contradiction of her:

So how do you know all this stuff? I said.

Through you.

I waved my hand, impatient. [3]

All of this adds up to a rigorously pursued relationship (perhaps even set of relationships, not with the artist Munch, but with the works he created. It means that Ali is able to determine why and when trees matter in his painting (even when absent to block the stressed air flows in The Scream. She learns how and why air becomes visible and over-and-enduringly present in The Sick Child too. In both the movement of the lungs in sucking in despair that still flies away from remedy is felt. Only Ali Smith in this book has taught me to see that – by relating to me, talking to me, relating to me (as she did with Joanne in reading Gliff – see my blog on that book at this link), without ever (really!) being in the room with either of us.

The issue with art is that it too soon turns, as does much in this world where money and power vie for dominance and empathy and community suffers, is that it too takes their model – sometimes in the form of the assumption of knowledge rather than the struggle to sense, feel and think around what we actually see in paintings. we defend our readings because we own them even when they lie in ignorance alone. Responding to her mother’s insight into the meaningful feel of a Munch painting, Ali retorts:

Well, he’ll have known, I said, won’t he, science and biology. He’ll have known _ I was trying to sound as if I knew the picture and knew about a lot of things that mattered in the world and was doing all right – that plant and trees need oxygen.

If you say so, the nineteen different types of ghost said in my ear, lightly scornful, like they knew I was faking. [4]

This is Ali at her brilliant best. People use a filler in speech, like ‘won’t he‘, to perform apparent consultation of the other conversed with, but rarely expect an answer. Rather it is a means of encouraging or forcing collusion with one’s own views. The sarcasric ‘If you say so’, gives away thatr the correspomdent is wise to those tricks. but another thing is wise here too. Ali has only just learned, from her Norwegian translator, that there are nineteen words for ghost in that language, each indicating a diverse identity. Even know she can’t help but boast that knowledge whilst acknowledging that sometimes we talk to other people as if they were a fiction (and a very flat character, at that, in E.M. Forster’s terms).

You must if you don’t yet really know Munch read this book – and if you think you fo, read it too and see if you are open to changing what you see, open to relating and not dominating your art with your expert knowledge or defensive attitude. of course I am a master of that last sin too. That’s why I read Ali Smith. For when art moves me or you it does so because ‘ … something between me and the picture felt poised on an edge waiting to happen, the verge of something wild’.

Joanne has decided not to buy books now or I would have sent this one to her. She will get the new novel, Glyph, when it comes out later this year whatever! A gift from Geoff and me, my love!

All for now

My love as ever

Steven xxxxxxxxxx

_____________________

[1] Ali Smith (2025: 8) So In The Spruce Forest Oslo, Munch Museum

[2] Despite appearances to the contrary this is what Milton surely says in the famous passage in Areopagitica: ““For books are not absolutely dead things, but …do preserve as in a vial the purest efficacy and extraction of that living intellect that bred them. I know they are as lively, and as vigorously productive, as those fabulous Dragon’s teeth; and being sown up and down, may chance to spring up armed men….Yet on the other hand unless wariness be used, as good almost kill a Man as kill a good Book; who kills a Man kills a reasonable creature, God’s Image; but he who destroys a good Book, kills reason itself, kills the Image of God, as it were in the eye. Many a man lives a burden to the Earth; but a good Book is the precious life-blood of a master-spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose to a life beyond life.” ― John Milton, Areopagitica

[3] ibid: 26

[4] ibid: 35

Much love dearest friend. Another enjoyable blog xxx

LikeLiked by 1 person

How tremendous my dear that you are support me even here, as, of course, you do throughout.The very idea of a thoughtful friend

LikeLike