“The Story of the Stone: Tales, Entreaties & Incantations“: the artist and shaman come nearest to us in sharing an acknowledgement of the opaque density of our experience. New short stories by James Kelman

I have already referred to this set of stories in a past blog [see this link to read if you wish].

Stories are commonplace and communal, but art is not, at leat in the aspect of its demands on its practitioners. This seems to me the base contradiction of James Kelman as an artist. No other novelist I know stands so adamantly by that name artist, finding in it some special status (though not one defined by the status of a social elite – but rather by work and practice), which is why I dare to use the word ‘shaman’ in relation to this status. It is a status defined by social allowance of a little bit of earned status in hard-won knowledge, feeling, and social action that leads to some acquired powers; in the learning of which others are unwilling to invest. I addressed some aspects of this in my blog on God’s Teeth and Other Phenomena (available at this link).

However, these stories are a clearer exposition of the Kelman contradiction; much clearer, for instance , than that book liked by Kelman but few others, Translated Accounts, though it bears much in common with the drive and comprehensiveness of these stories. The title of the whole book, of over 100 works, is also the title of the first story. It is the story of a social ritual of unclear meaning where the ‘I-voice’ initiates the passage of that dense opaque thing that is a stone from hand to hand ‘around the room’. The I-voice instructs his followers as to how to ‘hold’ the stone, but neither he nor others may ‘pass it along as though beyond reach’. We talk about our grasp of a story, idea or thing – the term comes from Piaget’s insistence that the primal motor-behaviours by which a baby tries to comprehend the world of things, by reaching and grasping, in some sense absorbing what cannot materially be absorbed, become the model of cognition. Yet in the story, the stone in this ritual is developed to a point in the consciousness of each person who grasps it wherein ‘it is, as it were locked in, do you feel it?’

Each person must know how to feel ‘it’ and understand the ‘work, work, see how you work‘ they do on it in this ritual before the I-voice re initiates the story’s ongoing motion, perhaps in nothing more than in passing it on again, with more instruction on how to hold, grasp and feel that which is transmitted. Perhaps the process cannot be complete until the whole group grasp that ‘the stone is of our species’, and recognises that by virtue of the work they have done on it that they can see that it is their nurturing of it that has given it the self-same substance as them, even though the stone remains a stone – opaque and dense.[1]

Is this story a ‘story’ or a ‘tale’? Perhaps its very ritual nature makes it an ‘incantation’? Perhaps the desire of the ‘I-voice’ to be seen as sharing and in-creating our humanity makes it an ‘entreaty’, a plea to share with respect for how much of himself the shaman-writer gives in the process of making art, of creating a communal understanding of things otherwise ONLY dense and opaque. Many of these stories question their own ontological status – as ‘what am I?’ When they don’t do that, as in the studies of the way the voice of bureaucracy and power masks art as something else (instanced in stories like Ulpi Non Reum, Your Ref HRMP432cB;34QQ, The Principal’s Decision); as something the very opposite of what it claims to be, an agency purveying only the means to the death of what might have been living had not its own agenda taken control (very much as in Translated Accounts).

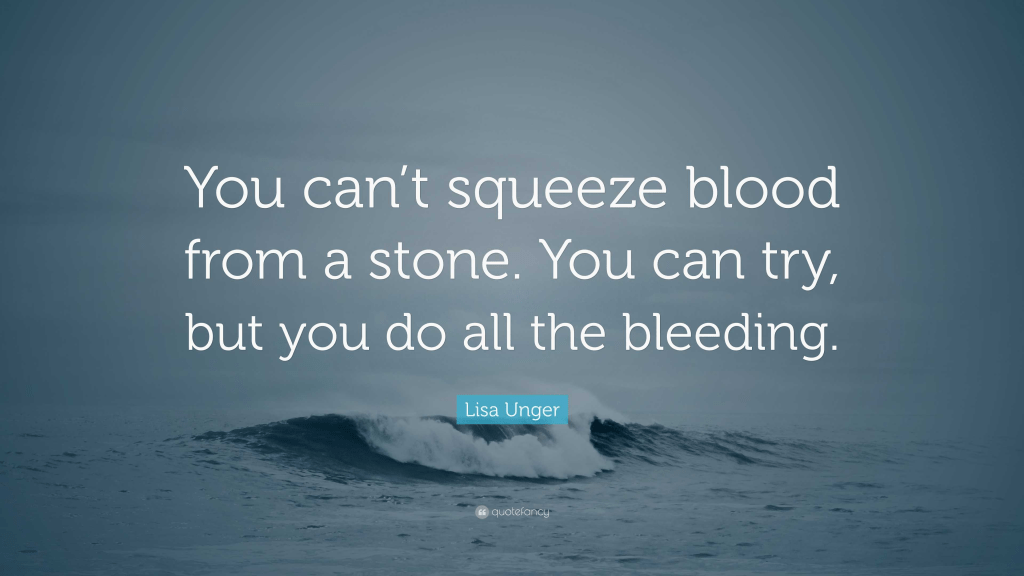

At other times, Kelman takes an experience where, you might think, it was impossible to draw blood, or any human fluidity, out of any stone we find on an Edinburgh street – stories about the truly marginalised, such as The one with the dog where the means of extracting money from those who have more of it than have they is the topic. However, turned over in the hand until we feel the humanity, our fear originally hid from us – for few readers of literature ever identify with a beggar on the streets of Edinburgh – we can see ourselves, living in the same species of experience, with a man who allows nothing to get near him – even a dog whom he treats like a male mate who once:

followed me about and that and I didn’t like it. I used to tell him to fuck off. That’s what I sometimes do with the dog. Then sometimes they see you doing it and you can see them fucking they don’t like it, they don’t like it and it makes them scared at the same time. I’d tell them to fuck off as well. that’s what I feel like doing but what I do I just ignore them. that’s what I do with the dog too, cause it’s best.[2]

Pass that around the human circle, feel its density and hardness, see how little it apparently shows to you and then feel your own hands, and the warmth remaining on the stone from other hands through which it has passed and learn that this story teller wants you to extend the humanity of which you are capable – even see it in yourself, rather than depend on the disguises your social role and mask encourages you to wear.

Even harder to understand and feel is a story like Governor of the Situation, whose I-voice inhabits the point of view of a rich person who tries to explain why they hate (it’s a strong word) that parts of the ‘city’ we have to imagine them traversing and experiencing in the way they, in particular, do: “- the stench of poverty, violence, decay, death: the things you usually discern in suchlike places. I don’t mind admitting I despise the poor with an intensity that surprises my superiors. ” It turns out that this man who thinks himself ‘the acknowledged governor of the situation’ (and therefore thinks others see him thus too) has a huge appetite – but for what? For whatever it is, it gets burned up in self-conscious ‘nervous energy’ of being ‘always on the go’. This is a story where someone other’s death and decay and other aspects of time ‘on the go’ are felt. Do you feel it, inside the hollowness of his ‘hollow pins’, the legs that transport him. [3]

Maybe faux ‘artistes’ have the hollowest legs and swallow the experience of marginalised others without return. But it can be a mistake not to see that it is the reader who turns a true artist into a faux one. Hence one fabulous early story The Sensitivity of the Artiste is spoken from the voice of a listener who thinks they know art and appreciate the sensitivity with which it works. However, if you have ever been to a Kelman reading, you might recognise some similarities in behaviour at least with the ‘artiste’ in this story and James himself. The density of this story resides in the self-absorbed nature of the lover of art, or so they see themselves. I cringed as the storyteller reported his words to the artiste on leaving the reading venue: ‘You were outstanding, I said, dont worry’. This might be to show that his cognitive understanding stood way above his human and emotional recognition of another human being feeling human things about the topics of his art, but at a level so comprehensive, it hurts. Readers can prefer the power of their own understanding to anything other in art. Do we realise that if we glance back at an artiste, we might find them ‘gazing off somewhere, alone in himself‘. [4]

For me the best stories are those that respond to suicides. One (A Hard Man) does it from the perspective of that supposed hard man – like looking for softness in a stone until we find it. Another (Our son is dead) gets nearer the universals involved, but they are not in the obvious abstractions this great story evokes: ‘Absurdity. Time and place. Meanings of life’.They may reside in an experience in which the father sees the ghost, or hallucinates such, as he tries to get nearer (his hearing is going) to find how – in the deep night – his wife is dealing with their isolation and potential guilt of survival. The mystery of the story finds its point (in Roland Barthes term its punctum – see my blog on that) in whether the door behind the vision of his dead son was open or shut – whether the suicide would let hin ‘in’, and if so what that might mean:

… I walked to the top of the stairs.

My son had appeared in the doorway of the bathroom. Did you want in dad? he asked did I want in. No.

I’m just going to shave, he said, the door swinging gently.

I saw it, the bathroom door, four panels. We chose it. The door shut. he shut the door. The hinges were not new. [5]

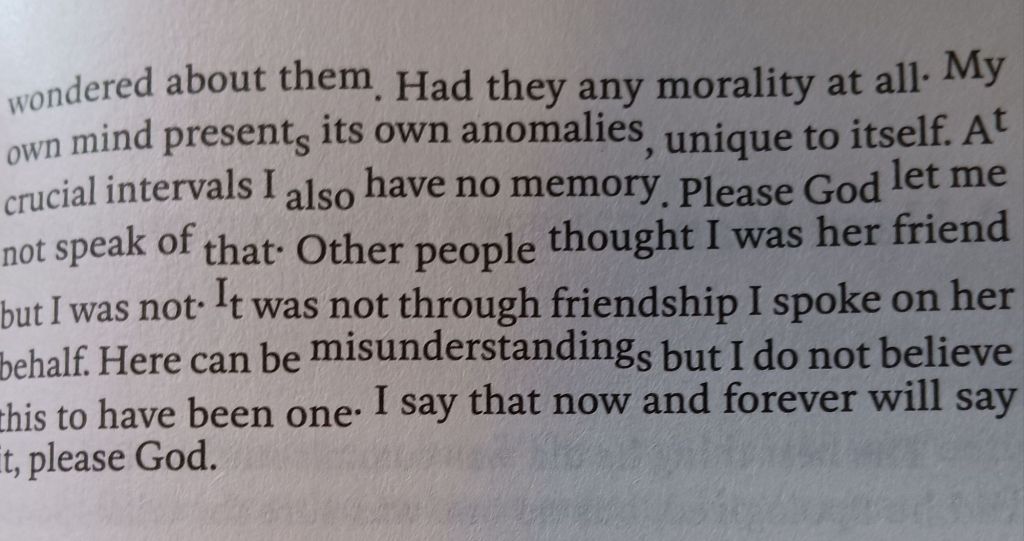

I know these stories all matter, for as soon as I choose a ‘favourite’ another pokes me in the ribs and surreptitiously takes its place in the hierarchy, questioning whether it ought to be a hierarchy at all. As with most people who love Kelman, we are on watch and ward most when he treats of sex/gender differences, especially in these heated times for that topic. One story that I need to come to terms with is literally wonderful and called A Woman I can Speak About [James Kelman (2025: 7141) A Woman I can Speak About in ibid. 140 – 141]. I can’t just quote it because it uses all the wisdom about font and space production that lies in Kelman’s own experience as a teenager, spoken about in his Introduction to this book, when he became a compositor’s apprentice in a printing company – also an aspect of the ‘work’ of art. So I will leave you with just this quotation photographed and no comment:

Bye for now. Read these stories though!!!!! They amaze.

Love Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

__________________________________

{1} James Kelman (2025: 1) The Story of the Stone in James Kelman The Story of the Stone: Tales, Entreaties & Incantations Oakland, California, PM Press, 1.

[2] James Kelman (2025: 182) The one with the dog in ibid. 181 – 182.

[3] James Kelman (2025: 33) Governor of the Situation in ibid. 33.

[4] James Kelman (2025: 7) The Sensitivity of the Artiste in ibid. 6 – 7.

[5] James Kelman (2025: 100f.) Our Son is Dead in ibid. 98 – 101. For A Hard Man see ibid: 142