‘… caught in improper possession of another person’s property’.[1] This blog examines the sensibility of the outsider’s desire to belong and have no belongings. Abdulrazak Gurnah (2025) ‘Theft‘ is a novel in a great tradition of ‘David Copperfield‘ & ‘Great Expectations’.

Karim, whose growth to total self-possession makes him the main contender pretender to be the hero of the novel, Theft, certainly feels he has an entitlement to belong – as a beloved son, school or university student, husband, father, and civil servant – to the institutions of normative society. Very early in the novel he learns this right to belong under the quality of self-possession that others attribute to him, just as he attributes it to himself, perhaps even to the extent of being domineering, as he ‘grew into a lanky, soft-spoken, self-possessed boy whose unwavering gaze sometimes disconcerted grown-ups’. All the elements of character development are here of this belated James Steerforth character. However, to get to the depth of this brilliant novel, that seems underwritten (but is not so) we need the lead up to that moment, at a little length, for in it we uncover extremely deeply set themes like bigger jewels hidden in an apparently modest literary coronet. For from the start Karim is recognised as a ‘little gem’. You have to absorb Gurnah’s unassumingly beautiful prose in long sections, for it does not veer from a kind of simple narration into obvious symbolism, never simplifies its characters without some psychological nuance. We know that Karim is a spoiled child – though there is a cost I think in being admired as a ‘little gem’, admired because he is your ‘possession’, as he is considered by his gorgeous and brilliant mother, Raya, but who nevertheless stops short of making his welfare, rather than his appearance of being special, the object of her ‘care’. In this passage, Karim’s school tells her of his brilliance, how in particular he outshines expectations set by his half-brother (brother with another mother), Ali:

In this beautiful and characteristic passage, the sources of the childhood treatment that reinforced Karim’s difficult personality are made clear: adulation and the setting of a model of social power and particularly the power of surface appearances and sounds rather than of empathy or the deeper meaning of lovely sounding names – to ’embrocate’ after all is merely to pouring lotion onto the damaged surface of the skin, not the deeper care that motivates it and which it symbolises. His models are all simplified versions of the heroes revised for the interest of male children: Hercules, Perseus, The Greeks inside the Wooden Horse of Troy ,and Sinbad but they are also all destructive beings: Perseus indeed known best by Karim in the fact of his beheading dangerous females that get in his way, as Karim will with his wife Fauzia. Fauzia is the more deeply learned reader of people, the world and books – her head is as dangerous to Karim, though he never realises it, as the snakes on Medusa’s head or her tendency to turn men into stone. The fact that disturbs his schooling is that the earth is not entirely hard and firm but molten in the middle.

Nowhere though does Gurnah tell us what we in fact are shown that being treated as a ‘possession’ is the source of both Karim’s ‘self-possession and feeling of entitlement in owning the right to be the hero of his own story, regardless of other characters: his wife and child Nasra (he is unable to express care for Nasra only ownership – his attitude lacks deeper effects of the embrocation afforded to Nasra by the more gentle Badar, who will earn the right to steal the role of father from Karim). This uncaring but real, if shallow, attention to others can be established without even mentioning Badar, who he assists, while doing so without caring about that which he assists lest it become dependent on him, and fail to go its own way, modelled on Karim’s way, at a lesser level. After all, he calls Badar a ‘wanker’ because he does not go away after he is helped but continues to haunt Karim and his wife. However, there is a sense that a nuanced writer like Gurnah must even show how disturbing Badar can be, even if you didn’t, like Karim, feel your self-possession and your worldly possessions that validate that self-possession (including family) were under threat of theft from this example of the undeserving poor. A model for this might be Thackeray’s attitude to Amelia Sedley the perfect heroine, and foil to the worldly and clever Becky Sharpe in Vanity Fair, for at the end of the novel he calls her a “tender little parasite”; a character without any possibility of development and change, except that she absorbs from those on which she leeches.

There is an element of this in Badar, as in his clinging to the life of Fauzia and Karim, despite Karim’s best attempts to loosen the attachment. Asked to ‘visit us whenever you want’, a formal and not literal offer that middle-class people often make, Badar takes it seriously; half-aware that his sensitivity to the noise of Karim and Fauzia having sex in the next room is part of the attraction:

He loved them both. … he watched them together and listened to them when they were in their room. He could not hear what they said but there were time she thought he could tell that they were making love. He tried not to watch them, tried not to listen to their movements in their room, tried not to feel neglected and envious, but he could not prevent himself. it was a surreptitious desire to share something of their happiness, but he knew it was not right. He knew they would be upset if they suspected anything, would think him dirty or even malicious.[2]

This feeling of being an object of malice – a thief, of love in particular but also its physical and material symbols enjoyed for their own right, in the manner of the woman Badar calls his Mistress – Raya. the mother of Karim – is constantly evoked around Badar’s journey in the novel to that state at the novel’s very end, wherein Badar contemplating his relationship to Fauzia and Nasra (Karim now a single man and rising bureaucratic politician) ‘began to seem that in some small way he belonged with them’.[3] Is there much about Badar that might rightly be named ‘surreptitious’? For there is in the passage something of the symbolic molten core of the novel right there: much of the novel exemplifies the deep networks that link the phrase ‘Belonging to’, as a phrase denominating the possession of something or the awareness of something being possessed (as a wife or servant can feel possessed in the novel) to the feeling of ‘belonging with’ a group that might have seem previously exclusive. How does this come about?

Being treated, or not, as a special possession as a child or chosen human friend or mate matters in the deep structure of this novel, and explicates the deeper reasons why the novel gets its name, Theft, for theft is a threat not only to those things which belong to you but to your capacity to belong to the world in an apparently valued position, a ‘little gem’, a thing no one should ever steal away from your belonging. It took me time to clarify this but that then is why I cite David Copperfield previously (and not because white people can only evaluate the contemporary post-colonial novel about black lives that matter by its ability to belong to its highly colonial great white traditions). This novel merely assumes the hopeless case of post-colonial whites, however otherwise innocent.

It awakes in this novel in the ignorant treatment of black people as the objects of Western charity or as the sexual toys of liberated white women, either consciously as in the case of Tina Derrick’s attempt to seduce Badar, or less so, in the throw-away attitude of the flute-playing charity worker from Gemstone Street, London, Geraldine Bruno. No white person may sense Geraldine as a racist, not least because she is sexually drawn to black men, but there is an attitude of ownership towards them and though she thinks she might like to read Fauzia’s well-read and valued copy (fundamental to the theory of colonialism as theft) Zarate’s The Discovery and Conquest of Peru and borrows it (despite Fauzia’s fear that it might be unconsciously stolen this way) returns it only very partially read and as not her thing at all. So much for white interests in the colonialism from which they distance themselves from being responsible.

But there is the fear of theft latent too in David Copperfield. That great novel starts with this portentous sentence, where its narrator queries whether this novel belongs to him and whether he belongs to it and is fitting for the ‘station’ of hero, for the novel will for a long time question his entitlement as such:

Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.

That trickery of Dickens is much more complexly handled by Gurnah, for the latter’s novel starts a long way from the person who, I will argue, is its emergent but true hero and possessed of that’s role’s values, without it seems requiring to enact any kind of theft of the right of those who feel most entitled to belong to the category or station of great hero. How do you steal the right to be hero of your ‘own life’? Is it a matter of being absorbed into other more obvious models of the hero by taking over their setting and belonging to it in your own right? If so it means taking possession, one way or another, too of having that model’s belongings. Certainly Karim feels threatened by Badar, if not in the obvious way fearing that he is a literal thief as Uncle Othman feels Badar is threatening, by virtue of being the orphaned son of a man who stole from Othman, Ismail.

People who are not possessed of things are the ‘have-nots’ of this world and when Badar eventually learns the story of his father Ismail, he learns how that once young man’s dispossession had still enamoured him to the easy-going Haji, Karim’s cousin by his mother’s second marriage, who engages him in his house to help his mother but when he returns from university finds that Ismail had got into the wrong company, become lawless, ‘stole the money master kept in a cashbox in his office and disappeared’.[4] Badar is brought into the house without knowing this and without any clue why Uncle Othman treats him with distrust, as if thieving were genetically transmitted. Yet the main link between the life-conditions of Badar and those of his father is their dependence on the wealth and status of others for income and respect of any kind. Without money, possessions or any formal or institutional learning – he is self-taught to read and he does this in part by mimicking reading Karim’s reading of detective novels, which interestingly enough he calls crime novels. Merely by virtue of ‘belonging’ to nobody, Badar seems destined to a life where it is thought that either metaphorically, physically or materially he will be liable to steal the belongings of others, those things that are signs of belonging with the society in which they live. He continually stands in line for accusations of stealth – the first we hear about being that of voyeurism, of ‘peeping on’ a girl one year older than he when she is dressing.[5]

Of course, we know Badar is aware of, and resents his lowered status amongst the people he lives – his first adoptive mother calls him an ‘innocent little rascal’ and then in his move to live with Haji At the age of 13, it is only to learn he is to be a servant not a family member. Only later does he learn that he was made ‘a servant to punish his father’.[6] Yet the word ‘stealing haunts him even when he enters the home of Haji for he tells an untruth that he is ‘still in his thirteenth year. He was almost at the end of it, and felt justified in stealing a march on fourteen’.[7] It is no surprise that, looking intently as he does Othman finds evidence of Badar stealing groceries, though Badar claims to ‘have not stolen anything’.[8]

It is a mark of the nuance of the novel that one can miss such buried metaphors in relation to the evaluation of Badar’s ethical status. From the earliest days of colonial literature, the savage man – a man of noble origin dressed and apparent truly feral haunted literate. There is a salvage man in Spenser, and Shakespeare uses the motif in King Lear, Cymbeline and The Tempest, echoing the idea of how and whether nobility of manner and behaviour can exist outside of known civilisations.

An eighteenth century print by William Kent of Spenser’s Salvage Man

In both Spenser and Shakespeare the ‘noble savages’ nearly always tend to prove themselves finally to be actual nobly bred persons acting as a savage man or brought to this lowly condition by strange circumstances, like Edgar in King Lear. The meme haunted later colonial ideas – finding all kinds of permutations, as in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness with regard to the Belgian Congo. Badar is a late son of that tradition, used highly ironically, as in this musing upon his status by Karim:

Karim wondered about the boy. Ali and Jalila did not have a servant, nor did Karim’s grandparents. He was not used to servants. The boy did not act like a servant. The servants he saw when he visited people’s houses were usually silently industrious, eyes cast down on their tasks, except for the odd one who had been with the household for years and had probably raised its children. He saw quite quickly that the boy, though discreet in his manner, was somehow without diffidence.

For Karim a boy like that needed to be watched and observed lest his apparent self-effacement were not really the signs of a ‘watcher, an eavesdropper, a future mischief-maker’.[9] The novel works because Karim, though himself a discredit observer of others by the end of the novel, for he too is accused, even if falsely, by the post-colonial charity worker colonial Director as someone who steals what belongs to another – and another white post-colonial agent.[10] The accusation of stealing groceries is itself ironic. Carefully Raja and Haji tot up what they eat and test it against what Badar has claimed to have bought, but this show of economy is entirely false. Though he does not steal as such, he notices that after Ramadhan:

Badar have never seen such plenty. Not all the food was consumed in the house. Some of it went to neighbours, and they in turn sent some delicacy to the house.[11]

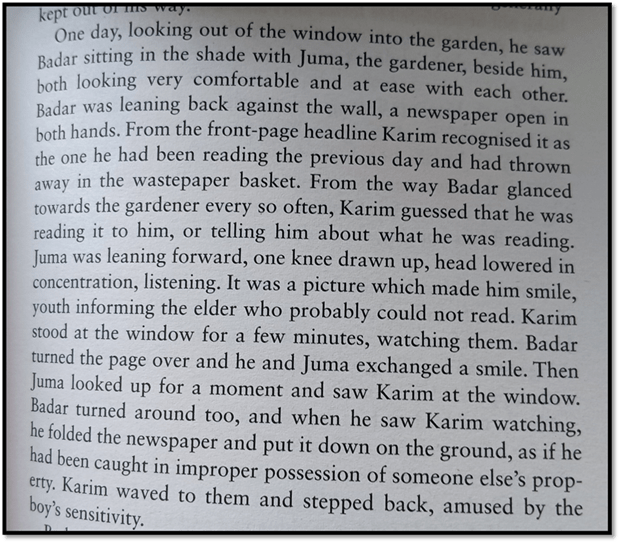

To notice such things would be good training for a food thief, and Gurnah strews such clues about as freely as any ‘crime novelist’ for us to detect. But they are not driven to conclusions. The case of whether Badar gains what he does – the place in Karim’s family and social place that Karim abandons after his affair with Miss Bruno – remains an open one, not a shut one. So always do great realist novelists work. See also another clue I love which I use in my title. In line with Karim’s discovery that Badar is no ordinary servant, ignorant of how to read and write like Juma and others in the novel, he espies Badar reading to Juma an old newspaper he has already discarded into the ‘wastepaper basket’. Read this carefully but note most the choice of metaphor that reveals both how Karim perceives Badar potentially and the possibility of some king of slyness and stealth of action in Badar, for it even contains a definition of what ‘theft’ is: ‘caught in improper possession of someone else’s property’ but only serving to describe a feeling that is analogous to, but IS NOT, theft.[12]

If Karim is condemned for the stealthy way he assumes the right to have sex with Geraldine Bruno whilst pretending to his wife that the friendship was Platonic and mediated through wife Fauzia, he uses Badar’s apparent (and I use the word apparent on purpose) sexual naivete to enable that affair, that might well have been an affair between Badar and Geraldine.

As we have seen, at the very end of the novel, Badar, a boy defined throughout as an outsider to human connection through family, community and even sexual contact learns to adopt to new belongings that are gifted to him – from detective novels to clothes bought for him, and thence to minor property with which he stuffs his flat. This is the process of beginning to ‘belong with ‘ others. That this includes the possession of validated sexual satisfaction has already been implied. He learns about men having affairs by observing what goes on in his hotel and taking it to Karim. Incidentally this allows him to learn Karim’s own looseness of sexual morality that will be Badar’s entry portal to taking his wife and child from Karim, whilst not appearing not to do so. This is all the more telling in that Badar’s first layer of sexual fantasy was for Karim’s mother, whom he calls ‘The Mistress’ (a wonderfully ambiguous term). Not the imaginary sexual fantasy in this reflection on The Mistress:

To Badar the Mistress was beautiful., especially when she had just risen from her afternoon rest and was dressed in a loose thin gown which sat well on her and clung a little to parts of her body as she moved. Her hair was often uncovered and tied back, revealing the clean line of her jaw, her high cheekbones and dark brown eyes which seemed to glow. It was in this garment that she played her part in the fantasies he tormented himself with in his darkened room.[13]

Is not there some evidence to a careful reader – one more like Badar or Fauzia than Karim I believe – that there is literal truth in some of the later accusations Karim makes about him. When Karim characterises Badar’s way of life he calls him a ‘useless wanker’ and he means that both really and metaphorically. It is in this light that Karim asserts his entitlement to the glittering prizes of post-colonial government and to white women who are looking for a sexual stud. Not being self-consciously entitled (as Karim is) is, Karim tells Badar, that he might as well masturbate ‘your life away’:

There you are living, living in that room on your own, masturbating your life away, and you think you can moralise on me.[14]

Karim is a rather poor reader. He reads thinly as he shows when he instances his reading of a Tolstoy story.[15] Fauzia reads not only about the theory of colonialism but also Victor Hugo, Dante, Shakespeare, and Plato’s Republic.[16] Badar has a library of crime books, probably ‘borrowed’ from Karim, that by the end of the novel he has outgrown.[17] And if you had not noticed, I think it is clear that Karim is as acceptable a sexual object for Badar as Fauzia, until Karim’s need to be the only dominant force in any relationship becomes clear. After all listening to the couple having sex through the wall is frustrating because he loves them both. When first he sees Karim the prose shows that his core too is molten, for Karim ‘had something of his mother in his appearance, those melting eyes’. He notices, with some pool of reserved feeling, how Haji touches him freely despite Karim’s own reserve.[18]

But I started by saying that there is a suppressed conflict in Theft, as in David Copperfield, about who will be the true hero of this story. It is after Badar’s first loving glance at Karim that he refuses at first to share his name with Karim. Why? Because, perhaps, the name Badar is the name with heroic proportion, referencing the Mohammedan Battle of Badr or Destiny. The sense that Badar resents being seen as an absurdity by Karim – as a servant who might yet carry a heroic destiny – speaks through the prose rather than being on its surface, I think, as if psychologically under the surface too:

Then [Karim] asked for his name and when Badar told him, he said, the battle of destiny, whatever that meant. Then he said that thing about his mother and father, them wanting him to be a hero. It sounded like he was laughing at him, making fun of a servant named after a hero.[19]

In my own mind, this is a good point to stop now. This novel will be considered by Booker judges because of Gurnah’s past successes in the Booker field, but I hope it proceeds too on this year’s list. But will everyone notice just how good it is?

Bye for now. With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Abdulrazak Gurnah (2025: 75)Theft London, Bloomsbury Publishing

[2] Ibid: 170

[3] Ibid: 246

[4] Ibid: 140

[5] Ibid: 42

[6] Ibid: 77

[7] Ibid: 36

[8] Ibid: 143

[9] Ibid: 75

[10] Ibid: 234 – 236

[11] Ibid: 63

[12] Ibid: 75

[13] Ibid:

[14] Ibid: 240 ‘useless wanker’, & 239 respectively.

[15] See ibid: 86

[16] See ibid: 90f., 108, 219.

[17] See ibid:127, 207 respectively.

[18] Ibid: 79

[19] Ibid: 79

2 thoughts on “‘… caught in improper possession of another person’s property’. Abdulrazak Gurnah (2025) ‘Theft’ is a novel in a great tradition of ‘David Copperfield’ & ‘Great Expectations’.”