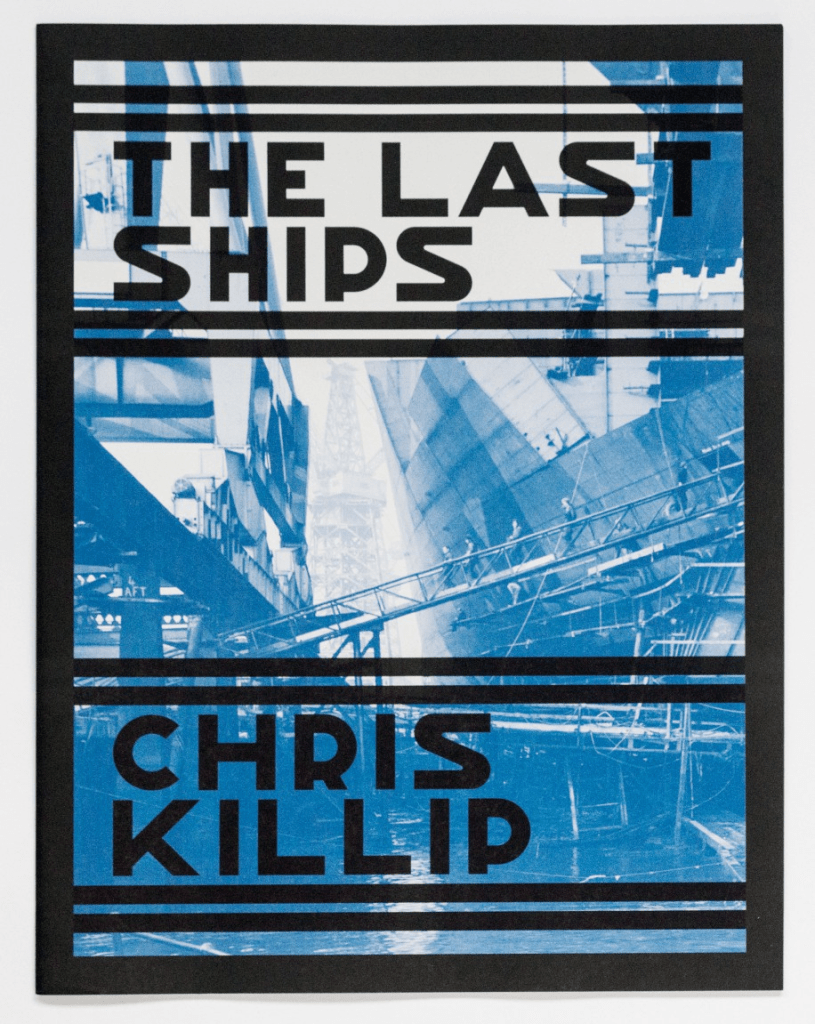

As I was sorting out my books again, I came across a book I bought at the Laing (pronounced ‘Laine’) Gallery in Newcastle when I visited the wonderful permanent exhibition there. It’s a huge book – the size newspapers used to be and made of a similar kind of paper. But how do you look at the pictures here?

Hence, I thought that perhaps the old recycled interview question used again as a prompt on WordPress might help me here. The question used is current in our times and expects a stock answer, or at least one based on a stock paradigm of what a worthwhile interviewee ought to be thinking about time as it passes. The frame for answering is to mouth pieries about Setting Realistic, Achievable and Measurable Goals, Checking and Monitoring the Realism of one’s Goals, Reviewing Progress towards those Goals on a regular schedule or in case of contingencies which threaten them,.. and so on. These answers constitute the usual transformation of personality into the robotic functions of being a worker, and only a worker [except in down time when we are a mindless consumer of the work of others] that capitalist growth economies demand that we be.

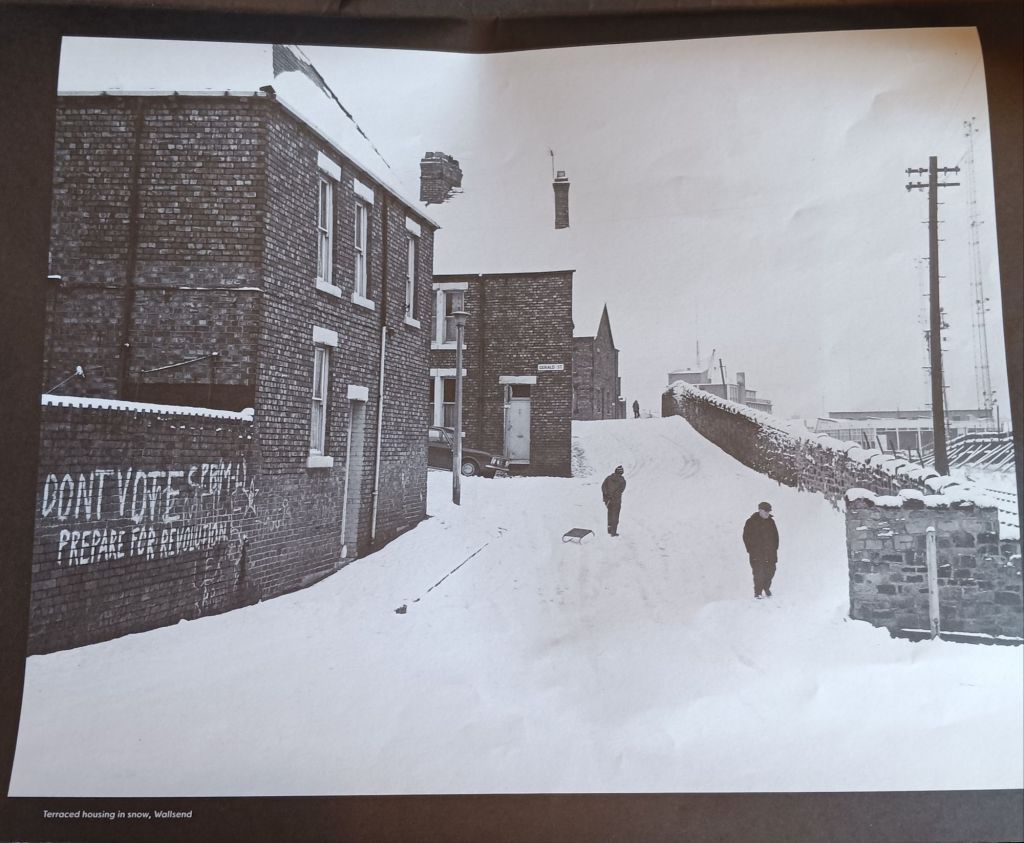

On my shelves, but hard to store and keep safe from aging, I found The Last Ships, and I pondered over it’s images, especially those of Camp Road in Wallsend, which ran alongside syreets and lanes of workers’ back-to-back houses descending onto it on the one side, and on the other a low wall defending the railroads serving the docks and the shipyards beyond them. Tall ships loomed over that wall, as if as eager to see up Gerald Street, as I am when I see those pictures. In one intriguing photograph, though, there are no ships in view. Was that because it was winter?

I don’t know if that was the case? For residents of Gerald Street, those ships would loom over them as they grew until they were finally launched to meet the needs of some trade or other or for military use. What you can see though in that winter is a piece of political graffiti from the The Communist Party of Britain (Marxist-Leninist), an offshoot of the British Communist Party with no faith in that party’s belief in a parliamentary British Road to Socialism. The graffito urges people:’ Don’t Vote: Prepare for Revolution’.

What was in Killip’s mind as he took these photographs? In fact, the answer, which I found as I catalogued my book digitally, was there. Killup took the shipyard pictures throughout his life in Newcastle but with no intention of making them part of his portfolio of professional work not wishing to be seen as an ‘industrial photographer ‘ – not then thetefore to be used as a baseline to show people interested in his pending career where he might go next. He is quoted thus:

“While I couldn’t help making the photographs of shipbuilding that I made, it was a personal obsession. At the time I didn’t exhibit or show them to anyone as I didn’t want to be thought of as an industrial photographer. I had a sense that all this was not going to last, although I had no idea how soon it would all be gone. I became the photographer of the de-industrial revolution by default, I didn’t set out to be this. It’s what was happening all around me during the time I was photographing.”

It is strange how Killip’s decision on whether to show these pictures was based on a question of whether shipbuilding on Tyneside would survive – for there may appear an obvious relationship between an impassioned art based on tbe recording of everyday life and a sense of that life itself, with its contingent other realities – terraced back-to-backs and narrow thoroughfares surviving with it – and even capitalism itself surviving despite signs of the unrest it also created and that made itself evident with painted marks on walls.

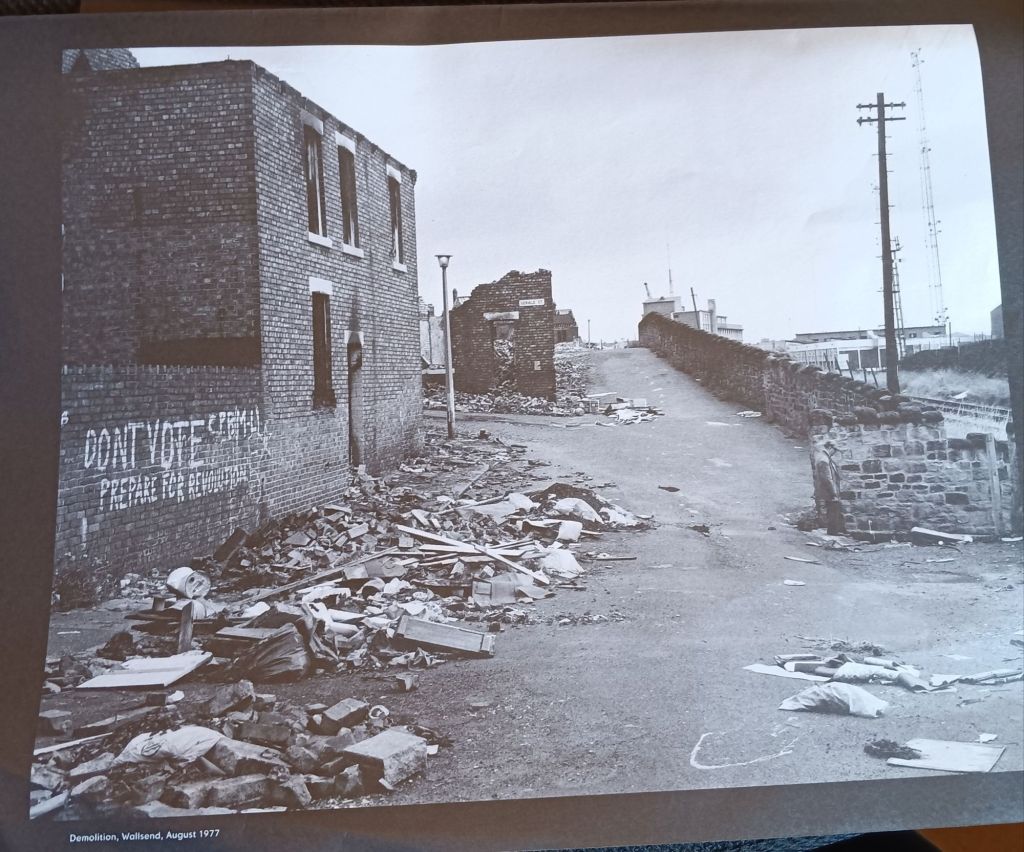

Killip discovers that he will be, but only, ‘by default’ and not because he predicted where he might be in ten year’s time, a poet of deindustrialisation. As his career grew, the jobs of the industrial working class disappeared. Did he think of the picture of Camp Road in the virgin snow (no-one is stirring, it must have been early) when he took the one below, where the grafitto is the only thing that has survived the cycles of capitalist production, and globalisation – whence shipbuilding sought cheaper labour elsewhere.

The wall is still there. So is the nameplate of Gerald Street, but otherwise, the signs of human life [hard life though it myst have been] are being slowly and messily pulled away. Even the road must be now unused because no one cares that rubble is now making it barely passable.

If Killip has become the poetic photographer of decline involved in deindustrialisation, it is evident that he did not want that to be focused on this Newcastle dockyards project, for they remained the ‘personal obsession ‘ he said they were.

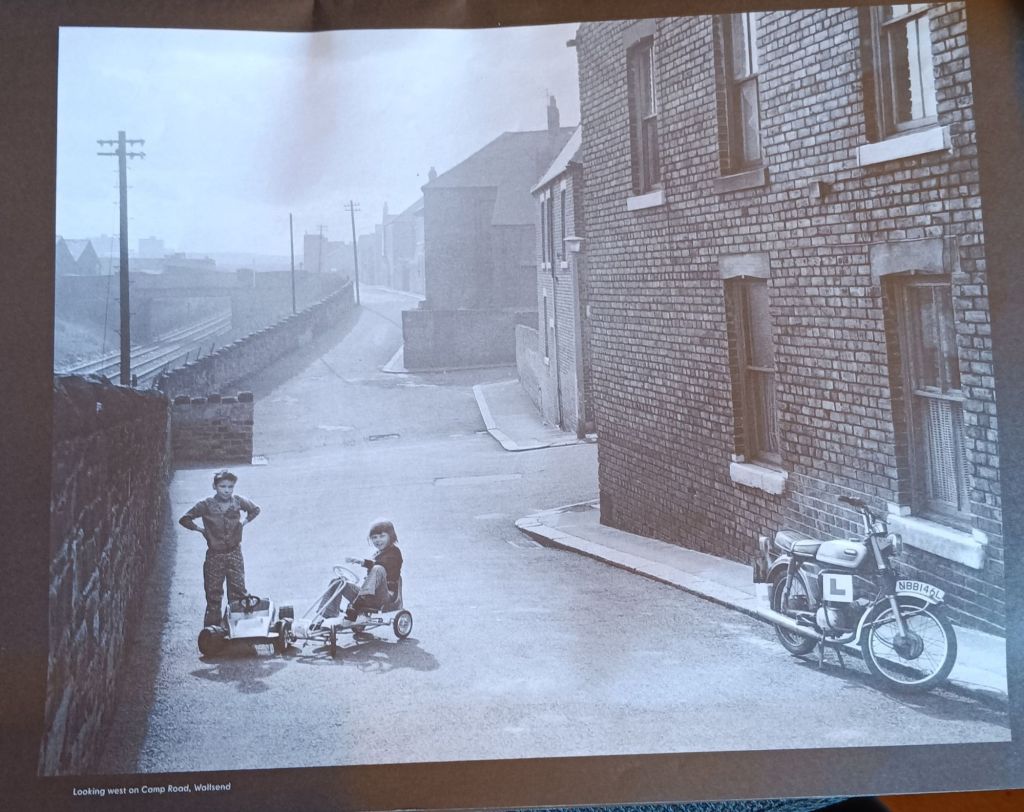

We can only guess from the evidence of the photographs. Here is Camp Street at the same joining of roads back at the time when it sustained life. The place is badly looked after – the roads are cracking and there are potholes, but the children here are playing happily enough and all are shod, which would not have been the case for their grandparents and perhaps even their parents. Their parents, the men anyway, clearly had access to work.

I suggest that work was accessible because a ship is there still being built, and, even if this was the last ship [which shipyard workers always feared], it increased their chances of ongoing employment , even if they were in tne group tbat had to queue daily to be chosen for dock labour. But there is other evidence. Tne polutuon in tne air from towers behind d meant that other working opportunities existed that might have .debit worthwhile to suffer having your children play in a noxious atmosphere. After all, you could afford to take them to Whitley Bay or Cullercoats.

And for children, the industrial scenes must have carried some excitement. Below a boy stands on his bike to see the work going on around an even nearer tall ship in the yard, with the moving trains and cranes that serviced it.

On another day, a cocky lad stands nearby where the boy stood on his bike in the preceding photograph, as we see Camp Road shooting away into the smoke-filled city [a sign there was work so not then an unhappy sight -it kept your big brother’s motorbike going] – cos when he’s learned enough he’s gonna take me on it.

In Camp Road, the question about its ten-year vision might have fell limp. there was only two years before it fell and the picture below when you could build a ship called Tyne Pride and hope that its oppressive presence was a shared kind of pride. But the value of memories is no more equally distributed than the prospects for a future that can be sustained, or is in your control. That was true for more people than Willy Loman in The Death of A Salesman.

All for now

Love Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

I’m a huge fan of his work. Saw many an exhibition of his down the years, most recently at the Baltic. I live in Newcastle though I moved up here after all those streets were pulled down.

LikeLike

Yes. Me too. Never seen the streets in the dlesh. The collection in the Laing is stunning, ain’t it.

LikeLike