Fritz Schein lives entirely in, and on as his means of living, ‘the art world’ of ‘spectacularity’ – a world of apparently random images and appearances that eschews the privacy of inner reflection by being in love with the still surface of mirrors. When the ‘great recluse’ Thomas Haller turns up at a show Schein knows he art world can be ‘pure spectacle’ . And for this it means that Thomas has been redeemed for the world that he only tries to shun. This will be his ‘lilac renaissance, his violet hour’.[1]

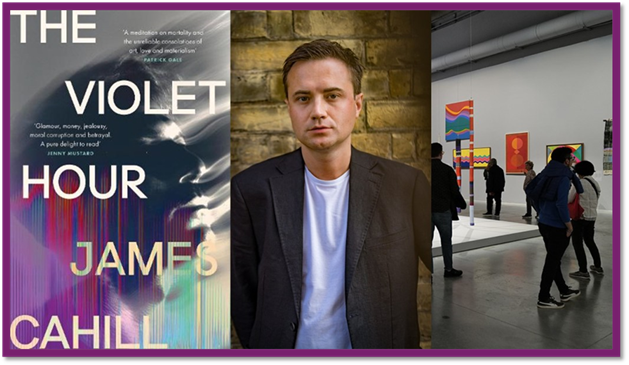

The aim of resurrecting Thomas Haller into a re-awakening, maybe even an entirely new life, is the aim of many in the novel The Violet Hour, but particularly that of his erstwhile lover and dealer – the former role enabling him to take on the latter – to whom he gravitates again at the end of the novel. He goes back to him for a second time because Claude suggests that Thomas needs ‘to be resurrected in a new market. He reckons China is the place’.[2] There is a prescience about the beautiful cover of the book that even suggests how that theme will be handled. Thereon lies the head of a beautiful male figure that seems both to emit and receive light but refract it into a flat abstract pattern of colours: not least tones and shades of violet. The splintered duality of the cover, where depth illusion jostle with flat surface effects, but here as if painted on a mirror with an image still showing behind it. Yet that image is one moulded by effects of light and shade and made to look as if not a mirror-image at all but as three-dimensional and with body volume. So many arguments in the novel can be tied to this idea.

Lucasta Miller, reviewing the novel favourably in The Guardian, says that around the central character of artist Thomas Haller, there are dual forces at play. First the force of a narcissistic ‘art world’ represented in Claude, whom Miller calls ‘ a Svengali in the shape of a European international art dealer’, continuing to elaboratehim thus: ‘Claude, whose sinister will to power emerges as we turn the pages at increasingly anxious speed’.

Opposed to her is Lorna who ‘had been close to the now fabled Thomas Haller at art school in London in the 1990s before later becoming his New York dealer’ These opposed forces she claims, ‘fight it out over the soul of Haller’.[3] This characterisation however does fit neatly, without making any claim that anything in this novel refers to the life, or even art, of Maggi Hambling (see that earlier blog at this link) with some concepts regarding the ‘art world’ that Hambling herself confronted – a world setting out the supposed goals, methods and the essential nature of art. An artist like Maggi Hambling, Cahill says, had to both conform to these demands and to privately diverge from them such that ‘a certain kind of artist represents’ what Hambling and Cahill call a ‘Steppenwolf’ type: that type being the icon of a double life where a private vision of one’s art or purpose can coexist with an essentially opposed view in public, where one can be ‘a public figure and yet fundamentally remain an outsider’.[4] The intention to invoke the duality in Hermann Hesse’s Steppenwolf novel may also be indicated by the fact that Cahill gives his artist hero the same surname as Hesse’s hero, Haller.

In Maggi Hambling’s case (the novel is dedicated to her), the duality operates around the enormous pressure on twentieth century artists to conform to the strictures of abstract art and its doctrines of impersonality, strictures often attributed to Clement Greenberg and their hold over Jackson Pollock, associated with it. The effect in Hambling’s Victim series of paintings which expunge ‘any sense of individual personae’ in effects that conflate the medium of the painting – marks made by oil paint – with any image that might be thought to be there but not to their author. As I put it in the early blog:

The figures in her art are so far from obviously being figurative that their boundaries blend with background and each other in the manner of abstract art, and colourist effects where the margins between colours are blurred: ‘pink swishes puckering up against a dark blur’. The effect of swathes of coloured brushwork matter in the novel. [5]

My perception from that earlier reading was strengthened as I continued reading, and merges with another perception from that earlier blog, which I expressed thus:

The process of Hambling’s art at this period involves a kind of play with the extent to which form may emerge from what appears both formless and unmotivated by obviously conscious meaning: Inchoate figures were painted she could not understand but ‘knew they meant something’ (5).

This play between conscious and unconscious in the formation of the imagery of art is yet another Steppenwolf moment. An artist can appease the critical need for achieving pure form, or what Clive Bell in England called ‘significant form’, without giving up on the meanings preferred by the human lives represented in figurative painting. These are the dual goals of the novel imposed on Thomas Haller. On the one hand, there are the strictures of Claude in the novel about the push to abstraction that Haller requires – a washing away of ‘subject’, ‘personality’ and even recognisable ‘images’. On the other hand, lies a lack of prescription and an openness to human life in Lorna, a human life associate with literary women in the novel – who quote and understand T.S. Eliot, George Herbert, and Henry James.

Let’s take the latter first, for it underlies another reference, in the title that ensures the ‘violet hour’ is not a phrase that can be entirely captured by Schein as iconic of a painter’s renaissance into abstract art. Haller is a man who characterises his past as a ‘collection of images in his head’. When this is said, Claude is in the only place he has ever called ‘home’, Montreux, and Cahill’s gorgeous prose evokes his past life in Montreux in a ‘heap of broken images’ (a line Cahill uses to characterise Maggi Hambling’s war-scarred-landscapes elsewhere) as a town that kept ‘flinging him out and reeling him back again’.

The image there from fishing lies uneasily in this landlocked place where only two ‘of his returns had the character of homecomings’. The Greeks called the homecoming theme a nostos (Ancient Greek: νόστος) story, and its formative pattern lies in Homer’s epic, The Odyssey, involving, as it nearly always did, the return of a ‘sailor’ of sorts. The pattern is repeated in Aeschylean drama, almost without exception, but with plenty of variation of the type of the ‘homecoming’.

But in another poem of ‘broken images’, T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land – itself patterned on the Greek theme – nostos relates to the ‘violet hour’:

At the violet hour, the evening hour that strives

Homeward, and brings the sailor home from sea,

The typist home at teatime, clears her breakfast, lights

Her stove, and lays out food in tins.

The unassuming reference to Odysseus (‘the sailor home from sea’) is undercut, but also reinforced, by the everyday νόστος of the typist ‘at teatime’. The pattern references the many homecomings that don’t feel as if they are such in our novel, for many of the ‘homeless’ alienated characters, even that of Thomas Haller’s. As Lucasta Miller insists ‘erudite allusions abound, yet there’s a thriller element that keeps you reading’. She is correct, but I think there is more to that than just the mark of a clever writer – though Cahill IS an exceedingly clever writer. Home is a concept ill-fitting in this novel and its ‘art world’. Again, as Miller says, here comparing this novel to the novelist’s debut: ‘the canvas here is broader, more global, more glamorous, cutting between New York, London, Hong Kong, Montreux. But the same theme – art and lies – endures’.[6] And home is one of the fictions of artistic lives. This is emphasised again by a literary woman, Marianna Berger, and her video Hotel, a place that serves as a representation of a homeless home, which she uses to contrast with the return of a lover to his once nest, but now as a guest. It is from George Herbert’s poem Love, though that reference is carefully not given, and is an allegory of a sinner’s return to a Church that loves him. Marianna recites in the film these words:

But quick-eyed Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning

If I lack’d anything.

It serves to contrast with the squalid hotel room housing Marianna’s life with Carter Daily, though yet unnamed in the novel, an art critic. The allusions here are obvious, if you know the poem (if not, read it in full at this link). The quoted lines refer to the actions that mean that a lover to whom one returns – or really returns to you – will make you feel ‘at home’ despite yourself:

LOVE bade me welcome; yet my soul drew back,

Guilty of dust and sin.

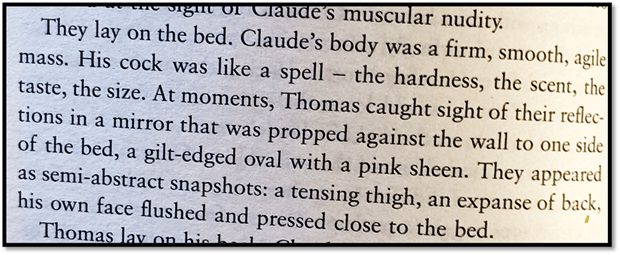

It may not describe a ‘homecoming’ exactly but it surely feels as near as the novel gets to the consciousness of what these characters lack, and are unwilling to find or re-find, preferring ‘straw men’ to Herbert’s ‘love’ – either in the micro returns Thomas keeps making to Otto for brutal loveless sex and in macro terms, continually returning to the manipulative Archimago, Claude, and his art of bloodless, homeless abstraction (described below as ‘semi-abstract snapshots’) and spectacles that are seen, if at all , in the mirrors of a narcissist’s abode:

My photograph ibid: 98

To these mirrors Haller keeps returning only to be cajoled into leaving behind him an art of humane and human-related ‘images’. Against Claude Thomas half-heartedly asserts his need for a subjective companionship with his ‘subject’, something meaningful between the subject and himself: “I require a subject, and the subject chooses me, not the other way around”, just as Luca chooses him. To which Claude replies: “Let colour be your subject, and form, and tonality. These are the absolutes in art”. Claude is a man of many nations and many languages but no real home – his role is just to leave it, leaving ‘a younger sister who never left the family home’.

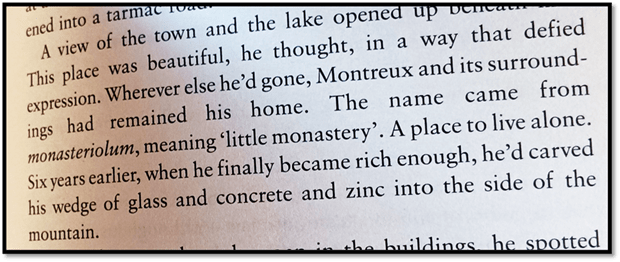

But there the Steppenwolf theme re-emerges. Thomas is next seen in Montreux and here is another man entirely: as a loner, an ascetic and locked away as if in that monasteriolium (‘little monastery). It’s a sumptuous (and not a ‘little’ one) prison cell he has hacked into the mountain, but one nevertheless, as allegoric as the cave of despair in both Spenser and Bunyan:

My photograph ibid: 101

The paintings that Haller makes are precisely those that seem empty and flat, with names like The Pink Paintings, it is not surprising that Justine, Lorna’s literary lover and soon-to-be ex-lover see them as ‘playing at being Rothko; variations on a colour theme.

That colour is increasingly a variation of ‘violet’ and is named differently by different persons as ‘purple’, ‘pink’ or ‘mauve’. It refracts sometimes as red, chiming with red art by other modernists compromisers between abstraction and figuration – like the colour and form distorted Matisse’s Red interior and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska ‘s Red Stone Dancer sought, and the latter owned by Leo Goffman, the ideal buyer of a heap of distorted images. Eventually, for the Venice Biennale, Haller turns to a subject of violet, red and pink that at last resembles real skin subjected to violence – ‘bruises, cuts and wounds rather than ‘pure’ abstract colour.

It is the perfect resolution for a split man who often invites pain inflicted upon him by violence described as pleasure or vice-versa. That latter named artwork seen at least twice with its name attached to the consciousness of those who see it , becomes in the housekeeper, Bonita’s eyes, nothing but ‘a red stone figure, probably by one of those European Modernists, squatted in an ungainly dance’.[7]

A taste of Matisse and Gaudier-Brzeska

It is a wonderful quality in a novelist as young, knowledgeable and wise as Cahill that he not only wears all this lightly but is liable to show that the art he probably loves is meaningless in some eyes and that meaninglessness is still part of its truth.

That is indeed the quality of Cahill as a writer and a citer of texts from an august literary and artistic past and its varied traditions. I feel I want to say that because Lucasta Miller suspects that, because he constantly refers to Henry James, he self-consciously adopts James’ particular kind of nuance, especially for his female characters. I would say that he both could and does, after a fashion, do this but that the fashion is self-mocking and as mocking of the European modernist model (at its best in the hands of fake Europeans likes the Americans, T. S. Eliot and Henry James) as it is reverent.

Miller says:

… (Henry) James’s comments on his own “fidget of composition” and finding “the next happy twist of my subject” are quoted here by one of the characters, making Cahill as self-consciously implicated a literary artist as the Master himself.[8]

Well yes!. However, the quotation from James is from the discreditable fake of a character that is Justine, and though unreferenced, is not from an abstruse source but from the famous preface to A Portrait of a Lady.[9] It refers to ‘the waterside life, the wondrous lagoon spread before me’. But though Miller refers to ‘the more subtle Jamesian nuances of this impressive novel’, she does not examine the prose itself, which takes pains not, or at least I think so, to be Jamesian. Take the moment when Lorna (Cahill’s nearest candidate for a Jamesian ‘lady’) is like Isobel Archer in Venice:

Venice!

As Lorna walked to the landing stage beyond the airport terminal, the smell of the lagoon hit her.

She boarded the vaporetto and sat in the canopied section at the back. The chugging of the boat, its meandering movement onto the open water, awakened feelings that only existed in this place![10]

The scene is Jamesian – the feelings associated ‘only’ to this place as being ‘sexual’ is developed in the next paragraph (James like other queer men of his time and place – Sargent for instance – was attracted to the look and care of gondoliers with their association of availability to rich Western tourists). The language, however, is self-consciously only aping and faking James tortuously beautiful sentence structures, tje standard of his attempt at a classical style. As Lorna shows, she is moving into such language only because it was so often cited to her by Justine. And if Justine is a fake, she is because she knows we live in a culture of ‘fakes;. She says of Haller: ‘This is art as pastiche, …. Art that has lost faith in art’s own possibilities’.[11]

Pastiche is a form of intertextuality, according to Wikipedia – a method that references and imitates, in veneration, other writers, or traditions. Being imitation it is also a kind of faking of an original, even if not primarily that. There is no doubt that this is also Cahill’s method as a novelist, And the art that is imitated covers a wide range, even other forms of pastiche art (for, in a sense, what art is not pastiche) like the films of Douglas Sirk, especially (a favourite of mine and clearly of Cahill) Imitation of Life.

The film posits the idea of life as imitation based on the story of a girl, born of a black mother and ashamed of the fact, who passes for a white girl and imitates that life. The novel’s method also manifests how the performance of life rituals is also often a pastiche of other styles and scripts for living. Lora Meredith, its key role, is a would-be actress wishing to make a living in the ‘imitation of life’.

The 1959 version referred to in the book is a Technicolour revision of the film by Sirk, making it is last film, though 25 years after the black-and-white version. Technicolour is indeed one of the modes of colouring forms part of the pastiche method of Heller. He thinks that in this film, every ‘frame was a thing of beauty, exactly lit, a montage of surface and depth’. But here, note that Haller cannot even think about the thing without pastiche of Keats’ Endymion (intentional or otherwise): ‘A thing of beauty is a joy forever’. Moreover, his own pink (‘alternating between mid-pink and rosy white’) abstracts, he confesses to Marianna, asking her to keep it secret, are based on details from stills (particularly of the blown-up detail of Sandra Dee’s costumery) from the 1959 version. Likewise, his later blue and purple abstracts are all abstracted from reproductions of images from life (‘Things I’ve photographed. Things I’ve seen’). [12]

Exasperated by Haller, Marianna informs the Venice art world of artistic ruse, supposedly to expose him as a ‘fake’, though her comments have little effect. Some of the themes of Tiepolo Blue (see my blog linked here) are also present here. His works for the Venice Biennale are a pastiche of wound motifs imposed on everyday photographs from a photo-booth of Lorna, though Justine insists they also imitate photographs of Lorna taken by her. Yet, according to Marianna as she outs him, his aim is only to win the golden prizes offered by the status quo: ‘If this exhibition doesn’t win the Golden Lion, he’ll kill himself’. [13]

The prize at Venice is indeed a Golden Lion (almost a pastiche of the reputation of Leo Goffman’s leonine imagined gold reserves) . I think the role of Leo Goffman, the rich art collector (although his supposed riches are in fact an illusion we learn, and, as much as they exist at all, are represented by his art collection. Art’s value, after all, is set by a market, and by impressions made on that market, and must perforce imitate its values, which in turn sometimes imitate values quite foreign to the world of exchange value – the world of Marxism. It is a fake Marxism – a kind of currency of the ‘art world’ that Lorna exposes as fake. Cahill plays games with this. When Haller pretends to her that he has won the ‘golden lion’, she says: “Fuck the Golden Lion.” He mimics this knowing his fate is with Claude and in ‘Production-line art’.[14]

But the game of Cahill’s patisserie is that he has already shown that Leo is a Golden Leo the Lion who, under a veneer and in dreams, knows he is being ‘fucked’ by the world: When his aging body betrays him into wetting the bed, it represents itself as a beast with its limbs ‘closed round him, pinning him down, penning him in’. In his dream he concludes: ‘The beast was trying to fuck him’, and he imagines it in fine detail until the ‘animal was inside him’ to the accompaniment of a ‘blinding pain’, where he ejects hot urine into his bed.[15]

Leo is exposed here as nothing more than a ‘poor bare fork’d animal’, no more leonine and if golden, only from a urine shower. At the very moment his expensively bought Thomas Heller is delivered. What I have been straining to say, is that life is the art world, but in other worlds too, is continually exposed to manipulative fakery, or, at best, pastiche of a’ real’ thing. That is why Cahill’s style is not attempting direct pastiche of Henry James, or Douglas Sirk or T.S. Eliot come to that, but a blending of styles and genres – queered romance and queer mystery novels, exploring the reality and fakery of ‘love’ relationships and other relationships, across queer / heteronormative boundaries as well as art world boundaries with lived life – including cusps lived in by Bonita and others in service of those whose life is supposedly art.

And that is why this novel is brilliant. Haller plays games with every art- never aiming truly for an authentic life. His aim in his relationship is not for a film from her that is a ‘lie’ – ‘tragic, searching, sublime – all the things the critics admired’, even though he knows this is not the kind of film she makes.[16] As he shows off his palatial hermitage buried implausibly into a mountain he arranges for imitations of life to be seen by her – but they are deeply fake. He launches into a tune on the piano: ‘A succession of major chords followed by a swooping plunge, tripping down the scale into odder, darker keys’. Even the sentence impresses with its pastiche of musical rhythms but the aim of Cahill is to undercut both the character and his own pastiche style: ‘She wouldn’t need to know that it was the only tune he could play’.[17] Thus are fakes made.

This thematic strand in the novel is taken up with scenes of men and women seen behind the fake eye of another thing – a video still camera, or the mirrors of Haller’s last exhibition in the book. Life is imitated and played as an imposition of reflected otherness by scenes seen through windows in which characters do not know whether they see each other or can be seen. It is so wonderful a piece of writing that I won’t otherwise but point to here.[18]

How then does an artist make real things beyond the pastiche veneers their media offers them as belated artists. And it is here, I think that the novel at its best owes something deeper to Maggi Hambling and their converse together as critic and artist working on one book of exposition of Hambling’s art. In my blog on that book, I spoke of Cahill’s exposition of the way in which Hambling’s war art handles time.

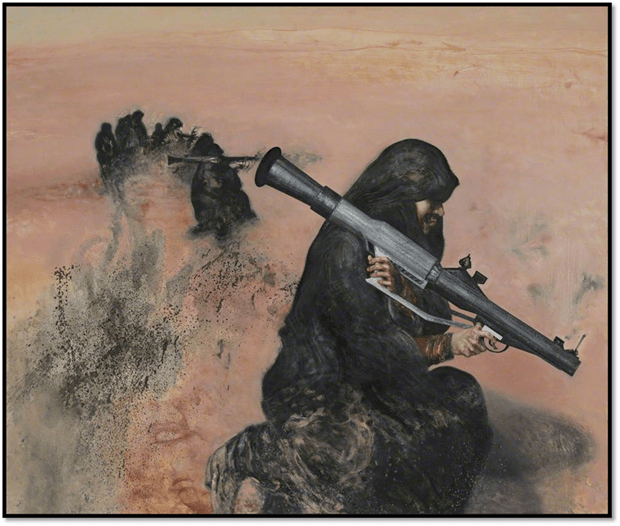

Art can dilate time, where a singular event in time and space can become symbolic of the ‘strangely eventless, yet speaks of events we cannot immediately divine’. Colour and form become abstractions of ‘a scene of charged expectation and frozen time – of nothing happening’ (66- 70), This occurs in Manet’s Execution of Maximilian and Rubens’ Samson and Delilah.

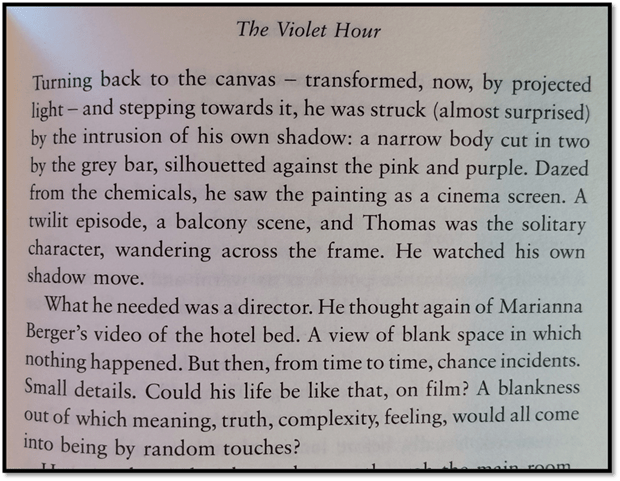

The latter quote relates To Hambling’s 1986-7 painting Gulf women prepare for war, a painting of women sitting, paradoxically, in a ‘pink painting’ (‘a pink-tinctured desert’). Based on a photograph, Hambling’s painting ‘developed into a scene of charged expectation and frozen time – of nothing happening’.[19] Compare that with this delicate scene in which Heller sees himself in a ‘twilit scene’ (one kind of violet hour) created by projected light and his imagination, ‘silhouetted against the pink and purple’, like the Hambling picture: ‘a view of blank space in which nothing happened. But then, from time to time, chance incidents’.

It is almost as if this is a pastiche of his conversation with Hambling. It was pastiche with extension and editing to a new set of circumstances, but based on the same aesthetic. In the passage, the subject is stilled occurrence, of occurrence that has not yet happened. I will end my piece by looking at the opening of the novel because this passage gently refers us back to that ‘balcony scene’ and forward to its retelling later. It is about how the very ‘pastiche’-like feel discerned in Haller by Justine might take us into new ways of thinking about the emergence of depths of art on a canvas surface, and of the motion of action (tragic or otherwise) in all its possibilities from ‘stillness (silence and stasis).

The first section of the novel set on balcony, at first surveys the scene from that balcony in a twilit violet hour like that in Eliot too: ‘The evening was so still that it could have been a picture’.[20] A picture is one which time stands still till a young man (we will later learn to be Luca, enters the scene. He mimes the Fall of Icarus because he seems to fall and stay motionless in ‘ floating on grey water’. This isn’t exactly of a scene in ‘time in which nothing happens’ but the prose style certainly seems constantly to stop or slow down a motion it cannot imitate: time and pace that is violent and sudden. If there is occurrence, it is slowed because ‘stilled’, and synonyms of are repeated throughout it and reflect on the rhythms of the passage of prose itself. Admittedly, the abrupt fall from the balcony gives us one nearly animated sentence, but it keeps being turned into static images.

I think this piece of writing, a pastiche of Icarus iconology from art and the fall of angels from heaven is full of longing because it is a ‘violet hour’, though in shades of ‘lilac’, whose meaning as an event has not been established and perhaps never is in the novel. Luca is the novel’s mysterious heart dissatisfied because Thomas is as passive as a sexual being as is he.

So there you go. No conclusion, but aren’t the best novels always thus.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx

[1] James Cahill (2025: 61 – 62) The Violet Hour London, Hodder & Stoughton

[2] Ibid: 329

[3] Lucasta Miller (2025) ‘The Violet Hour by James Cahill review – art, secrets and lies’ in The Guardian (Wed 19 Feb 2025 07.30 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2025/feb/19/the-violet-hour-by-james-cahill-review-art-secrets-and-lies

[4] Maggi Hamling with James Cahill (2015: 48) War Requiem & Aftermath London, Unicorn Press.

[5] Ibid: 18 – 32 (the intervening pages are illustrative images from the series)

[6] Lucasta Miller, op.cit

[7] James Cahill (2025) op.cit: 334. For the named and attributed statue see ibid; 30f. & 113.

[8] Lucasta Miller, op.cit.

[9] It is cited in James Cahill (2025) op.cit: 141

[10] Ibid: 279

[11] Ibid: 24

[12] Ibid: 239 – 242

[13] Ibid: 302

[14] Ibid: 329

[15] Ibid: 244

[16] Ibid: 161

[17] Ibid: 176

[18] See ibid: 70 – 72.

[19] Maggi Hambling with James Cahill op. Cit: 70

[20] James Cahill 2025 op.cit: 3