Growth and hunger create awareness of ‘hollow spaces that never existed before’: Tash Aw’s The South focuses upon the lives of queer ‘angry young men’, and even boys grown as wild as El Niño. But are both responding to an extraordinary and new ‘physical evolution stronger than’ any of us or merely to ‘the effect of the weather’. Even to evoke ‘growing pains’ is an insufficient explanation because what is growing may not be benign to our health and welfare as people or societies. And, when all is said or done, on our present global trajectory, there will undoubtedly be times when we don’t know whether ‘the distinct sensation of the air turning soupy and unbreathable, of being suffocated by the very thing that was keeping’ us alive is a phenomenon in the external or internal worlds we inhabit, or both, in a reaction to unrestrained economic growth so malignant that the reaction to it comes too late.[1]

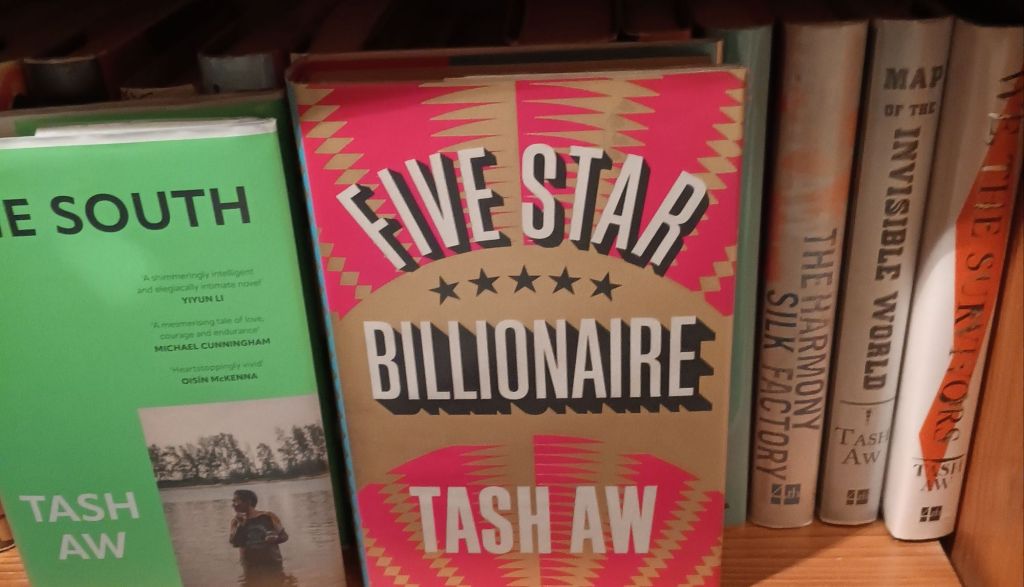

I have long been a fan of Tash Aw’s novels, as my closing picture of my current library shows, but this new novel is like no other of his that I have read, not least because it is the first of his where queer men overtly take centre page – the opening chapter starting with an incident that it takes a long time for the temporal sequence of the novel to catch up with: the hero Jay’s first experience of penetrative anal sex from his gorgeous half-cousin Chuan in an orchard of dying tamarind trees. Yet that the author plays tricks with time in his novel is in part the message and one that will no doubt magnify in effect in future writing of sequel novels since this one is intended as the first of a quartet. The critic Lara Feigel also considers it a new venture for Aw, and she picks up especially the references to disjointed awareness of time between the two young men (16 and 19 respectively). She writes in her review in The Guardian:

Jay, who has longed for this for weeks, wants to draw out the moment, so that “whatever time they have together will feel like many hours, a whole day”, while Chuan seems to want “to accelerate each second and collapse time”.

This choice of illustrating the difference of response to time between the boys applies to the most elegant expressions of it in the novel but all expressions. This is because Fiegel thinks that what we are seeing here is Aw’s debut the writing of a ‘Proustian quartet’:

Aw has moved beyond his previous novels to discover a different kind of writing here, emerging as a Proustian chronicler of momentary bodily and mental experience writing on a compressed, exquisite scale. Perhaps he will follow Proust in using his newly revealed capacity for blending the timeless and the historical to reinvent what an epic can be.[2]

Though Fiegel clearly gets what is going on, as I show soon, her need to see the time theme in the old-fashioned binary of evoking time within a ‘timeless’ framework is fatuous at least, whether applied to Proust or Aw. The whole point about time in the former is its perpetual exposure that feels whole and complete to experience of its actual fragmentary and unfinished reality, and I suspect this will be so of Aw too. As a result of her preoccupation with conventional notions of the ‘timeless ‘ in literature, even when Fiegel gets thing right about the novel’s experience, the experience she selects for retail is highly selective, missing some of the grit of the novel’s handling of time, even if not its refined moments of philosophical reflection about the nature of memory and speaking or writing a narrative, fragmented as it is by varying temporal durations between event, differing memories of it and the telling of it as different stories in differing contexts.

Already in that opening scene, Jay’s adult voice intrudes. “At that age, what does either of them really know about time?” he asks, and time lies in wait as a preoccupation that the book will have to confront. This is a story about people who are both waiting for life to begin and living with an intensity they will look back on for ever. Jay is precociously aware of this, drawing his fingers over Chuan’s skin, “trying to work out how he will remember it at a later time, what words he will use to describe it later”.[3]

If you read that first scene as I do, one senses quite a lot of contradiction – the adult Jay does seem to think young people lack a sense of what time is but it is Jay alone that thinks this means that youth is meant to be the period of ‘intensity’ adults miss out upon. But is this really so? The boys’ abstract sense of time as narrated by Aw in the persona of the elder Jay differs but this is not a simple matter that can be brushed over by a generalisation about the binary distinction of adult and youth responses. After all, what strikes the young Jay in Chuan’s love-making is that he ‘comes’ far too quickly for his wish to savour the sexual experience. Yes, the elder Jay turns that capture of time as different for each participant in the event but his words are his alone, never Chuan’s, and tend to overinterpret and/or and interpret negatively, Chuan’s attempt to take pleasure in the moment. It is ironically romantic, the elder Jay knows for his young self to make experiences feel longer, as cited by Fiegel and quoted earlier by me (so that “whatever time they have together will feel like many hours, a whole day”) but it also an act of overthinking by Jay to say that Chuan “wants their first moments of closeness to be over as swiftly as possible. To accelerate each second and collapse time”. In the second quotation I give more of the novelist’s words than Fiegel to show the propensity of Jay to over-interpretative dismissal of the value of Chuan’s thoughts and feelings about time, love and closeness.

In that sense, Jay is to Chuan as his father, Jack Lim, is to Fong, the latter’s illegitimate half-brother and Chuan’s father. Both Father and son are divided by unequal access to wealth, opportunity, education and resources to grow their talents. It does not surprise me that Guardian culture gets that wrong, especially in its disrespect to the uneducated. Fiegel does notice that: ‘Aw is brilliant at compressing sociological insight into intimate scenes, and here the boys’ differences of wealth and education emerge implicitly’. What she fails to notice is that Jay’s supposed greater sensitivity and beliefs about the elongation of the feel of time has more to do with these insights that with describing simple differences of our estimated evaluation of each of the boys. Jay presents himself as learning the limitations of Chuan as a lifelong lover, something Chuan says he wants in that first scene. Middle-class readers may find themselves equally beginning to attribute Chuan’s deficiencies to his character as a whole. Certainly they would if they do not notice that to describe, as Fiegel does, Chuan as ‘feral’ is a grotesquely insulting thing to do, even of a character in a social-realist rather than fantasy novel. The youth we read about as reflected in his behaviour rather than description by Jay is not a young man left ‘to grow up feral and barely schooled’. After all this phraseology misreads the fact that in the events of the novel the resourceful intelligence of Chuan rather than the rote book-learning of Jay is the more useful set of skills and resources in every way, except that they are never resourced by capital being made available just as Fong’s economic projects are not likewise resourced.

When I read this novel again and its hoped-for three sequel novels, I hope not to be looking for effects of the timeless in bourgeois literature but for a much more comprehensive notion of time that is not confined to Proustian ideas about the construction of memories in their recall (the madeleine), their malleability to learned perceptual processing and the tricks of literary narrative, with its selective word and syntax sets. And read properly, The South is very intelligent about time over a range of its domains – Time is experienced by characters not just in inner expectations and recall, that is in simple psychological terms, but socio-psychologically as a feature of the social management of birth, death, and ageing through social institutions, of work patterns and routines, of appropriate management of resources of land, capital and ecological developmental features of climate and its effects on the base elements on which we live – the earth, its waters, its winds and motive forces.

In another review of the novel that wears its learning much more lightly than Fiegel and otherwise than in this respect has less nuanced insights, Jane Wallace of the Asian Review of Books, says:

Fong, who lost his wife to the bright lights of Singapore, is trapped by financial hardship and realises he “has been in a box all his life, unable to break free.” The same goes for Chuan, who is desperate to escape the dead-end town and its homophobic denizens. Meanwhile Jack, with whom the buck stops, views the farm as an endless money-pit and is keen to offload the burden.

Aw deftly reflects these contradictions in the description of the family’s surroundings. The environment can be beautiful but it is also spoiled. He writes about the river:

A flock of white birds, maybe egrets, were standing on its banks, almost motionless, among the pieces of plastic bags and tin cans caught in the caked-over mud.[4]

That last quotation picks up the implicit notice of ecological breakdown, the starving young eagles, motionless water and the dominance of the waste capitalism is geared to produce and grow more in profusion than substantial goods of life. Wallace’s conclusion is less political than it should be. Fong’s poverty is constructed by the ideologies of his, and everyone else’s, pre-structured and socially determined global society. In truth, Fiegel captures some of this better than Wallace, at least the issues of ecological change. Read this lovely snippet:

Our present cycles of drought and flooding were already happening in Malaysia in the 1990s. The orchard destroyed to make way for a building project is a symbol of a lost way of life, as for Chekhov, but is also indicative of larger threats to the climate.

The link to Chekhov is both brilliant and minimising, at least in as much as it fails to raise class as well green politics: an issue, of course, in Uncle Vanya as well as The Cherry Orchard (see my blog on this at this link and this). Tash Aw, like no other writer, holds dear a belief that everything in the personal is political – even our desire for the timeless, which is indeed the most reactionary of desires. But for a queer reader, this is at its strongest in the theme that binds this book – that of personal loyalty and fidelity.

I am sure this is not a theme in opposition to divorce, arrangements of polyamory or rational approaches to distribute the roles in loving childcare. Any novel that pretends that any quality is timeless and faith a transcendent value forgets that change is the fundamental thing in life but that loyalties to each other can be sustained through change. When we do not, we bring about static and reproducing injustices that forever separate the brothers Fong, Jack and their offspring. When Jack, like Fong throughout, suddenly too gets the rough edge of the system and is made redundant and plunged into poverty, it is Fong who must yet again pay the cost to ensure Jack stays afloat while Fong sinks and that is the tragedy of this novel – for the economically poor most of all, Fong and Chuan. Fong is more intelligent than is credited. He knows he need not live forever under conventional static and unfair category labels: he just has not the social power, as Jack does, to influence his situation.

Wife, mistress, abnormal, normal. Fong knows what they mean, and how they categorise the world neatly, but the distinctions they create always seemed so arbitrary to him.

Jay as narrator elaborates that Jack continues to think negatively of Fong, or at least Fong thinks so and no-one contradicts him. Jack thinks through the bland and stale conventional myths of a society that blames the victim for their own misfortune: ‘What can you expect from a man of that upbringing’; ‘He is the son of a bar girl’ (even if his own father’s mistress).[5]

In queer relationships no-one has truly thought through the issues of fidelity and loyalty in relationships and certainly not beyond easy binaries of monogamy or polyamory. Yet this novel seems set to do so. In fact, yet again Lara Fiegel almost gets the point here, again when speaking of the difference between Jay and Chuan as lovers:

What’s painful in these scenes between the boys is that Jay is more involved, moment by moment, than Chuan is, because he’s more committed to erotic experience. He is, though, half-aware that Chuan is more involved in the relationship as a whole, while Jay knows as they drive to their first nightclub that there will be “other men on other roads leading to other towns”. Jay at 16 is already the writer, seeking experience, and the book’s preoccupation with memory becomes not so much a theme as a way of life. What makes the novel so masterly is that questions of memory are embedded in the structure with an apparent casualness that saves it from feeling overly engineered. Jay shifts between past and present, first and third person, as someone might shift about in their seat: trying to get comfortable, to inhabit these moments as he experienced them at the time and as he experiences them now.

This is an amazing passage to read because it shows, though I do not know whether Fiegel sees it thus or would welcome this interpretation, that Jay engineers his loyalty to people he loves by creating separated spaces for them in scheduling autobiographical time by mentalising it thus. Jay rationalises that the future of his desires and their objects will change because he knows, as Chuan knows better, that educated relatively richer boys have more sexual capital than Chuan once he is no longer the ‘hot’ young man, ripe to live as a gigolo as Jays’ sister knows and articulates his likely prospects in life (as a rent boy).[6] When Jay makes that point about neither boy knowing what time is and does, he is reflecting on Chuan’s simple words: ’I want to be with you. Forever’.[7]

There is, I think, a strategy in Jay As a planning whose plan is that his future queer love-and-sex life aligns with prospects he, like his father thinks of as their inherited entitlement (not necessarily a conscious one but one that fits with the social cognitions appropriate to capitalist societies divided by class) that self-interest trumps love, loyalty and commitment as a guide to development and growth. The personal growth that our society believes in is not unlike the belief in growth as a defining necessity of development in capitalism. For that economic system knows that no abstraction such as love or loyalty is worth staying still for, rather than moving on, in time and space, towards new ventures. And it is here where the novel is brilliant. Loyalty to dying tamarind trees is a kind of luxury in this novel and Fong ends by cutting them down and clearing space. Moving on and / or returning to a place you thought you had abandoned forever are the motive forces of its plot lines and characters in this novel, with only Chuan knowing how to create a more flexible framework of comings and goings within it.

Even in the love-making in the first chapter, Jay knows that it matters to someone whether the lovers in it are ‘boys’ or ‘men’, though he says he thinks it doesn’t, and at the same time dedicates his faith to a belief of the right to grow, and stay where they are, of aged rural trees: ‘Cutting down a tree is worse than killing a human being’. Both are positions from which Jay must move on, even before the end of the chapter, to ensure that no commitment is made to Chuan beyond the present duration – however much he might prevaricate later to stay within it and not ‘return’ to the city. At the end of the novel the young men [or boys] debate about the puzzle of the duration of things, almost speaking (but never quite) of the endurance of their love. They are, after all, discussing whether and when Jay will return to Chuan’s flat with the plenty of space in that Chuan emphasises. Look with me at two contingent paragraphs and feel their complex emotional structure:

Tash Aw (2025: 273-274) The South London, 4th Estate

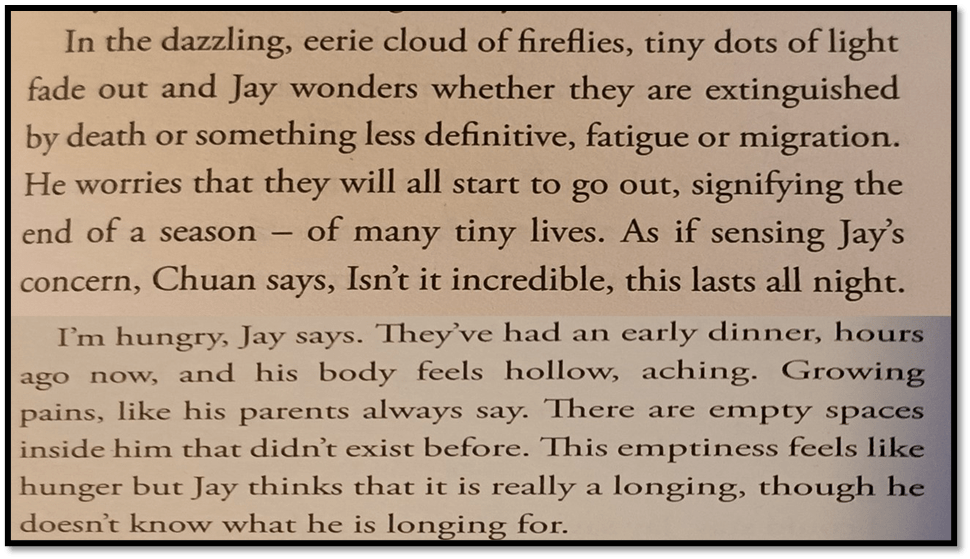

Aw writes, with great finesse, of a moment of heavily interpreted sense perception that leans towards the making real of the emotion accompanying endings – not just death but ‘migration’. It is as if pain is rendered into an element that can be directly perceived when that pain is moulded by concepts and developments beyond ourselves, like the movement of global markets and the power of social ideologies. But whose point of view sees these psycho-global events in the fading of firefly lights? The prose is ambiguous. The whole is definitively written, and we remember the author is meant to be the elder Jay, as if ‘Jay’s concern’. But that conditional sense– that ‘As if’ – is interesting because it implies either that Chuan also sees as Jay sees, despite the constant reminders of his difference from Jay, or that his care for Jay sees the equivalence of threat to their love in Jay’s abstraction. This is great writing.

But it is the more so when made contingent to the hunger Jay then expresses, and the generalisation of that hunger in the whole paragraph to the idea of ‘growing pains’. These pains are imagined by the sensed feel of vacancies within oneself meant to accompany growth – of ‘empty spaces inside him that didn’t exist before’ which is either ‘hunger’ or ‘longing’. And thereafter this is the crux of the way the novel structures itself – desire is central to its drive but desire is, in effect, ‘a longing, though he doesn’t know what he is longing for’, and one indistinguishable from the very different kinds of otherness Jay might long for – in union with Chuan or in moving on into what the bourgeois world considers his inheritance. The idea is reminiscent of at least one of the ways that the Freudian psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan formulates desire, here expressed in a piece from lacanonline.com:

… we can never ‘simply’ desire. Our desire is not something innate inside us. Indeed, for Lacan our desires are not even our own – we always have to desire in the second degree, finding a path to our own desire and our own recognition by asking the question of what the Other desires. We have to desire things that are desirable to the Other – whether other people or the Otherness of our socio-cultural context – and through that process the desire of the Other becomes our own.[8]

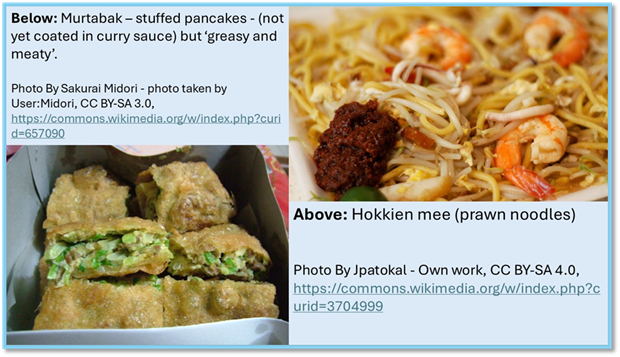

In the novel’s symbolic structure, hungry desire for food, and acts of eating, matter a lot and have resonance not only with fuel for human growth, but the psychosocial nature of that growth. What to Jack Lim is ‘peasant food’, and yet ‘good for you’, is ‘fit for Emperors of China’. To Fong. The half-brothers play out the debate as if it were about the values associated with high and low status and the mix between them that explains their accidental genesis from one father from two mothers of differing class.[9] Fong remembers the young ‘lean, ravenous version of the twenty-year old’ Sui, Jack’s wife, as ‘always hungry’ even whilst Sui herself wonders how her ‘different metabolism’ then grew into the woman who sits emotionally and socially starved with her husband Jack, Fong’s brother, with whom she sits ‘through dinner in silence’.[10] In the same way Jay sees Chuan in terms of a man coming into being on the food of the classes for whom fine dining is alien. One superb scene takes the lovers through a gargantuan meal of ‘greasy and meaty’ street food. Chuan opts for murtabak. Jay pretends to demur about the excess of food to appetite. Nevertheless, he eats as much as Chuan and even licks curry sauce from his hand, though he is also pleased that Chuan buys him tissues in register of his delicacy of educated taste: Chuan –

… ordered extra curry sauce even though I told him not to – it was too much and we wouldn’t finish it, and he said he didn’t care, he was in a good mood and he was hungry. …/…/ We finished the first order but were still hungry, we could have eaten exactly the same thing again, but I suggested getting some Hokkien mee instead. …[11]

Chuan pretends to as much refinement as he must to feed the inner sense of his social superiority over Chuan that will later assert itself as it did in Jack with respect to Fong, but he likes the rough food he gets: it represents and is associated with Chuan’s love and sexual hunger – however speedy in its sexual delivery. Youngsters male and female are associated then with a lean ravenous desire for growth, and these rough appetites are associated with ‘growing pains’. When Jack instructs Jay to grow up, he wants him to grow like him with a ‘slender, bony outline’ that ‘accentuated his severity’, but this is before he meets Chuan, though neighbours sense, and tell Jack that there is ‘something funny’ about Jay as he develops. To Jay himself the process is still inchoate. As he says: ‘There had been a lot of talk about in recent months about me growing up, but no one could really explain to me what that process involved’.[12]

In the terms the novel develops, in its repertoire of well-designed symbols that range from abstract to very material and interior to exterior, growing up and its pains are associated with discovering spaces – in time and space- wherein to grow. And this is true of capitalist economies too which in growth often clear the remnant of old means of self-sustenance – living land lost for tourism to thrive, agricultural peasant production to mass industrialised versions. Hence cleared or empty spaces are often symbols that sit between signs of change in the external world and of personal psychology. Empty spaces are those to which growth into the otherness of our desire leads us for us to fill them with them with the temporal, and themselves passing, outcome of our desire. The final chapter is in the clearing made of the old tamarind trees that Sui, Jay’s mother, knows to have been beloved by husband Jack’s errant father. It is these tree Fong dreams of cutting down to make way for his holiday chalet project for rich American tourists (a bit like Trump’s plan for Gaza). Here Jay says farewell to Fong whilst thinking that he is ‘just about to turn seventeen, and at that age, what did ii r really know about time?’ Time reconfigures desire and hence Jay is still learning about whether he can return to Chuan after leaving. After all, even swimming in the space of a lake can reconfigure that space if we lose its lateral qualities by diving to its depths before returning to the surface. Underneath we cannot discern each other as individuals through the ‘murk’ but:

When we surfaced we were each in a completely different spot from which we thought we would emerge, a haphazard arrangement which we all found hilarious’.[13]

Chuan is always making space for Jay but Jay never genuinely commits himself at any point to filling it. After all, he learns about queer lives at school precisely in a space ‘encircled by thick undergrowth’ and protected by its reputation for ‘unknow dangers’ but a ‘place to escape to’. Associated at first by Jay with the ‘smell of loneliness’, this queer space is sometimes filled by other more obviously ‘femme’ boys escaping tough sports and ‘styling each other’s hair’. Schoolboy Jay finds himself there one day with another boy who passes as entirely straight, but their touching (once disturbed by fear of public exposure) models for him the homophobia that is a choice for queer boys who pass as not thus . The names he acquires are: Cina, babi and bapuk, Chines pig faggot pig Chinese faggot pig Chinese. [14] Are these the names he later hears hurtled at Chuan in the vulnerability of the latter’s poverty whatever his bodily beauty?

With Chuan he finds a different space in which they might touch each other unseen. It derives from a story, perhaps a myth, of Communist occupation and hiding. It is twenty or thirty feet in extension from its entrance and cut off (and thus named a ‘shelter’ and ‘hideout’ but with an entrance that ‘looked like a cave’) from the mainstream like that school space earlier that may or not have been carved out by other queer boys.[15] Even when he visits it with his sisters in tow he finds its virtue for secret lovers, perhaps lovers alienated from social visibility:

It was a place built by people who didn’t fit in elsewhere.

When he stopped talking we crouched in the dark, and listened to the silence. There wasn’t much space and we huddled close to each other. My thigh was pressed again Chuan’s, his skin damp against mine> I felt his hand reach for my knee and come to rest there; I placed mine on top of his. It felt as though I could hear my heartbeat.

“Is it safe Here?” Yin whispered. “It feels as though the whole ceiling is going to collapse?”

Jay knows that to stay loyal to Chuan’s love is not only to share his manly beauty and the exciting male smells that he both exudes and inhabits in his work (the novel is brilliant at evoking these covertly) but vulnerability economically and socially too. Better far to keep the object of desire both shiftable and consistent with worldly success and inclusion. We need to remind ourselves by quoting a passage from Fiegel I quoted above because she gets the relationship so right:

What’s painful in these scenes between the boys is that Jay is more involved, moment by moment, than Chuan is, because he’s more committed to erotic experience. He is, though, half-aware that Chuan is more involved in the relationship as a whole, while Jay knows as they drive to their first nightclub that there will be “other men on other roads leading to other towns”.

Are the lines Fiegel quotes innocent? They seem to almost cite Mary Chapin Carpenter’s song and its theme – there about a woman giving up a man and finding others in ‘other streets and other towns’:

Now sometimes I just lie awake and I hear the wind

Blowing through the seasons of my heart again

My dreams are mostly lost and found on other streets, in other towns

But babe, you know, I still look out for you[16]

If Carpenter laments a man she had to give up, so is Jay lamenting the abandonment of Chuan. How that works out, or in hope does not, II cannot wait to see. However, my point is that Jay’s desires are bound up with the desire for a self that he knows need not hide: one that may have to compromise its form of queer being in line with one that permits social inclusion without the need overmuch to change society.

There is more to say but I have for now shot my bolt. Nevertheless, I cannot leave this without referencing my speculations in my title thus:

Even to evoke ‘growing pains’ is an insufficient explanation because what is growing may not be benign to our health and welfare as people or societies. And, when all is said or done, on our present global trajectory, there will undoubtedly be times when we don’t know whether ‘the distinct sensation of the air turning soupy and unbreathable, of being suffocated by the very thing that was keeping’ us alive is a phenomenon in the external or internal worlds we inhabit, or both, in a reaction to unrestrained economic growth so malignant that the reaction to it comes too late.[17]

The citation here presents the stifling feeling of abandonment and rejection, in its agent or recipient, as if it were like the choking environment of a world gone toxic to continuing human, and other kinds of, life. The ‘metaphor’, if it is that is what we might confidently expect if we as a world follow the disastrous trajectory towards global mass extinction of many species and the inevitable disordered imbalance in the gaseous layer of the planet that global warming must involve.

My feeling is that this, as much as any ‘Proustian quartet’, is what we might expect from Aw’s continuing narratives in this sequence to come. Not just a study of the distorts of memory but the real oncome of disaster in global economies, ecologies and the individuals determined by them. We might have choice still but it would involve the novel reconnecting to the themes of rebellion against norms of Aw’s earlier oeuvre. Thus it is with writing genius. I rest the novel now in my library of Aw novels and wait.

This is a very important book. Please read it.

With love

Steven

[1] Tash Aw (2025: 252) The South London, 4th Estate. For ‘growing pains’ see, for example: 33, 103, 106, 274,

[2] My emphasis in quotation, otherwise this is Lara Feigel (2025) The South by Tash Aw review – an intimate epic begins | Tash Aw | The Guardian in The Guardian (Thu 13 Feb 2025 07.30 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2025/feb/13/the-south-by-tash-aw-review-an-intimate-epic-begins

[3] ibid

[4] Jane Wallace (2025) ‘ “The South” by Tash Aw’ in Asian Review of Books online (10 February 2025) available at: https://asianreviewofbooks.com/the-south-by-tash-aw/

[5] Ibid: 140

[6] Ibid: 251

[7] Ibid: 5

[8] What Does Lacan Say About… Desire? – LACANONLINE.COM https://www.lacanonline.com/2010/05/what-does-lacan-say-about-desire/

[9] Tash Aw op.cit: 58

[10] Ibid: 71, 68 respectively

[11] Ibid: 126f.

[12] Ibid: 33

[13] Ibid: 163

[14] Ibid: 87 – 94

[15] Ibid: 179f

[16] See Mary Chapin Carpenter – Other Streets and Other Towns Lyrics | Genius Lyrics https://genius.com/Mary-chapin-carpenter-other-streets-and-other-towns-lyrics

[17] Tash Aw (2025: 252) The South London, 4th Estate. For ‘growing pains’ see, for example: 33, 103, 106, 274,

4 thoughts on “Tash Aw’s ‘The South’ focuses upon the lives of queer ‘angry young men’, and even boys grown as wild as El Niño.”