‘For our family and others like us, separation is an expression of love. Not just in the physical sense, but in the way we think’. [1] The obsession with a certain interpretation of attachment theory in Western culture was always in practice racist and a simplification of human neuro-flexibility. This blog is a reflection on distance in memoirs after reading Tash Aw (2021) Strangers on A Pier: Portrait of A Family London, 4th Estate.

As I waited to meet my frien at the theatre in London, I visited Foyles and found amongst the books in the ‘new’ book lobby, a brief memoir of Tash Aw that I assumed followed on from his latest novel – destined by to the classic of growing up queer, in my view The South (I blog upon it at this link). How wrong could I be, but was nevertheless glad to add another book to my little library of Aw’s work. I soon learned that the book was an expanded version of a book from 2016: The Face: Strangers on a Pier, a series of short recollections from his life.

When Petrina Fernandesz of Options magazine asked him how it differed from the 2016 publication, Aw said:

This new version takes the form of a long letter to my late grandmother — things I would have liked to say to her, things I’ve learnt over the years, perspectives I’ve gained now that I’m much older. But it’s a letter that isn’t really a letter – it branches out to incorporate the experience of living abroad, of trying to establish a notion of “home” in other places than Malaysia. I talk about my time as a university student in Britain in the 1990s, of travelling as a professional writer, of encounters that made me think of my position in relation to Malaysia.

The original edition was an extreme distillation of my thinking about several Big Ideas relating to home and belonging at the time. I didn’t have any answers then, so it ended up being a set of questions, more than any kind of solution. But I always wanted to expand on it, and lockdown – being forced to choose where “home” was – was the perfect opportunity to reflect on how my thinking had developed over the years. Friends who’ve read it say that it’s spikier in tone, angrier, but to me, both old and new editions are underpinned by a sense of melancholy, and even, dare I say it, of love. [2]

A letter is an interesting form. Even in early epistolary novels, the form depended on communication across a distance – that might be in physical space and a time difference but also a social distance and power differential as in Richardson’s Pamela, where a young girl in the service of a master, Mr. B., is the object of that man’s powerful desire for possession of her, in one way or another.

That space of distance is the location of Aw’s thinking about a number of concepts that zit uneasily in the border or on the threshold between between feelings and objects. Take the concept of ‘home’ and belonging. When asked at the printed end of the interview ‘And where is home now?’, he says:

Somewhere I can get rice and kari ayam. I don’t even need nasi lemak – I’m not that demanding. [2]

Here is a moment of identification of feeling and object I recognise from the later novel, The South: those objects that are consumable and intended to promote memories of home, love and belonging by their capacity to promote them from the fact of their ingestion.

Kari ayam [bottom – a Malaysian chicken curry] served with nasi lemak [top – rice cooked in coconut milk]

The theme will grow until it reaches the richer forms it takes in The South, where questions of familial identity extend to take on the case of queer identities, although one addition to the 2021 Strangers on A Pier to the original The Face of 2016 was also the reaction of his grandmother to queer ideology – in the unspecific and deniable form of a consideration of the artist, Prince:

He wears a thin moustache (sic.) and eyeshadow and mascara and a flowing red chiffon scarf, a heady unfamiliar mixture of masculine and feminine which, years later, with a new vocabulary, I will learn to describe as gender non-conforming, or in some way Queer, but at this moment I am merely transfixed, I am beginning to think about the way I want to live the rest of my life.[3]

The fact that Prince can only be described as in ‘in some Queer’ is important – identification with a way of living remains at the level of labelling a new mode of life from a distance of actually living it: even more so in the psychosocial label of ‘gender non-conforming’. The story is told however because looking at Prince on the new colour TV he remembers his grandmother as not acting as, at that time he had expected: ‘saying something disapproving, or even order me to switch the TV off’, but as in some way happy to accept the images that ‘transfixed’ young Tash, ‘swirling and multicoloured, as if obscured by halucinogenic smoke’. [3]

Home, then, is not a place in the past but that moment where the past is loved because it gives way to the future and refuses merely to hold on to the growing child, insisting they stays where they ‘belong’. Is then a family imagined as perpetual; ‘strangers’ a better more healthy model of that august institution, the family, with its control of everything that remains familiar – like a family that embraces queer options distant from its origins. The original titl;e of the germ of the book The Face is still the title of Part 1 of the 2021 book, witjh its concern that prompted it – that people recognise in Aw’s face is the source of the reception of it as anything the beholder might wish it to be, within certain limits: [4]

What Tash finds in his face is the formula of transferability and transitionality: ‘malleable, moulding itself’ as Prince’s face does. We all yearn for the other to ‘Same-same like me’, he argues and when not brand the distance from that ideal as alien, someone deliberately refusing our desire ‘for everyone to be like us’. Indeed in the film Alien, there is often a face-off- of the home face and the alien one. The alien starts its process of take over moreover by masking the human (and white) face.

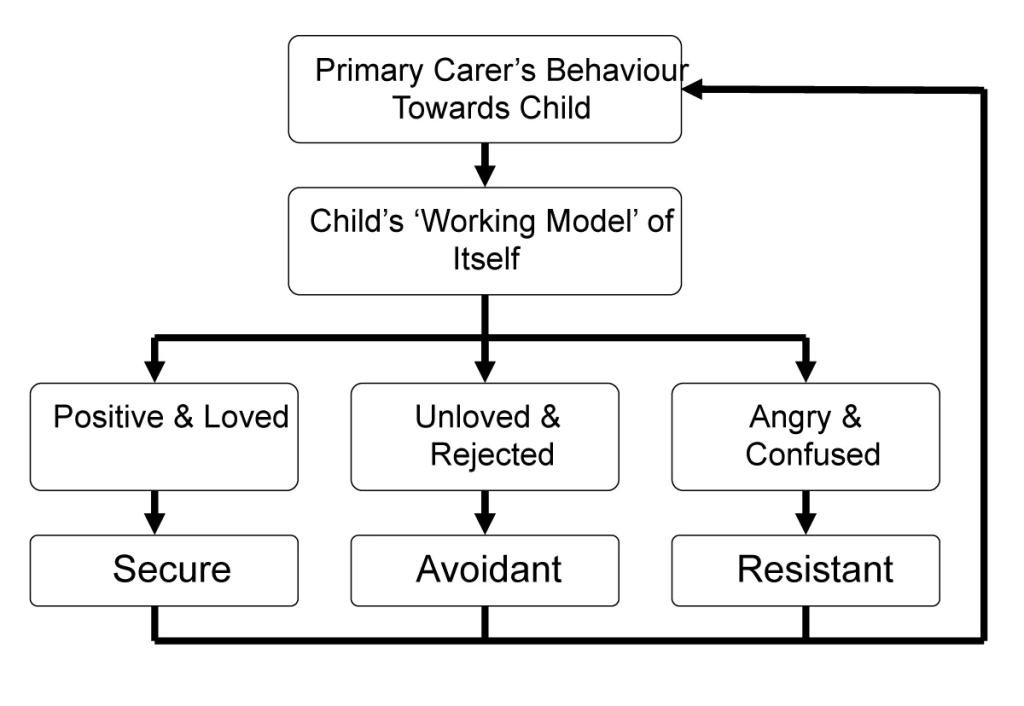

Psychological models of Attachment have always stressed the theory of a ‘secure base’, a space either exterior or interior to the person from which the idea of personal comfort springs. I say ‘interior’ because most of these models are translated from descriptions of childhood experience to models of how we think and feel about ourself and our needs – cognitive models – actual more accurately called ‘cognitive-affective models’. It is in the interiorisation of that secure bases of identification and security, it is argued that allows the growing child to find itself secure in encounters it either finds or is encouraged to find alien to themselves. In his Options interview, he queries whether “anyone’s views on the world and their position in it could have remained static over the last five years”, citing the effect of the first Trump presidency, Brexit, Bolsonaro, Orban, Covid, GE 14 , ‘amongst many, many other things’. The result he argues is any ‘flimsy sense of security and optimism we might have felt has been rocked’ and he had been ‘forced to confront questions of identity and belonging, of narrowing borders, even though I haven’t really wanted to’. But in doing so he invokes the language of attachment theory and its models (anak Malaysia by the way means ‘child of Malaysia’) :

People often speak of citizenship and the state using parent-child language. We are said to be anak Malaysia. And since we are Asian, being a child automatically means being dutiful – it means looking after your parents, being respectful, not speaking out of turn, not criticising. I don’t think this is a useful way to talk about the relationship between the individual and the state, but even if it were, what would we expect our parents to do in return for that filial piety? Wouldn’t we expect them to be, at the very least, nurturing and protective? To be vaguely organised? To try not to constantly undermine each other? To avoid treating their children as if they didn’t matter, and to provide love and support and safety to all their children equally? [2]

It is, I think, the increasing discourse of attachment and ‘belonging’ to a fixed, stable and objective ‘home’ (by which we mean ‘nation’) that has become the guiding interpretation recently of attachment theory as a natural preference to the needs of those ‘alien’ to us, that trespass on our borders and boundaries – physical and psychological. It is the discourse that allowed a Labour Prime minister to make a speech on the nation of the United Kingdom thus:

Nations depend on rules – fair rules. Sometimes they’re written down, often they’re not, but either way, they give shape to our values. They guide us towards our rights, of course, but also our responsibilities, the obligations we owe to one another. Now, in a diverse nation like ours, and I celebrate that, these rules become even more important. Without them, we risk becoming an island of strangers, not a nation that walks forward together.

Of course, Keir Starmer has apologised for the ‘island of strangers’ phrase (saying he had never heard of a similar phrase used by the racist politician Enoch Powell) whilst endorsing the meaning he intended by using it – but the point is that attachment to each other has now become a responsibility, a rule that forces us to be alike in our sense of what constitutes a boundary, to be ‘attached’ to each other – or else. In a sense he has made it a matter of legal and customary practice for all of us to have the exact same sense of ‘belonging’. But so much of this is antagonistic to what attachment ought to mean, which is to celebrate not our ‘sameness’ but our ability to become different – from our present selves and each other – to celebrate transition and diverse becoming that celebrates the expansion of home by its acceptance of that once considered alien, as Aw’s grandmother does by saying what she saw in Prince was ‘very nice!’

Think of the distance of the phrase an ‘island of strangers’ from a ‘pier of strangers’, or indeed Blanche Dubois’s beautiful comment – though sad for her in that that what she was to receive in getting to an ‘asylum’ was not what she desired – that she ‘had always relied on the comfort of strangers’. A pier in the West is most often a useless object in which the same old entertainment is dished out merely because it is ‘familiar’, to the point of staleness, piers in Eastern cultures still suggest a point of embarkation to somewhere and something else and families meet on them, says Tash Aw, to celebrate their coming distance and estrangement from each other – in the belief that that, not clinging on is the true measure of love and belonging as a cognitive-affective fact.

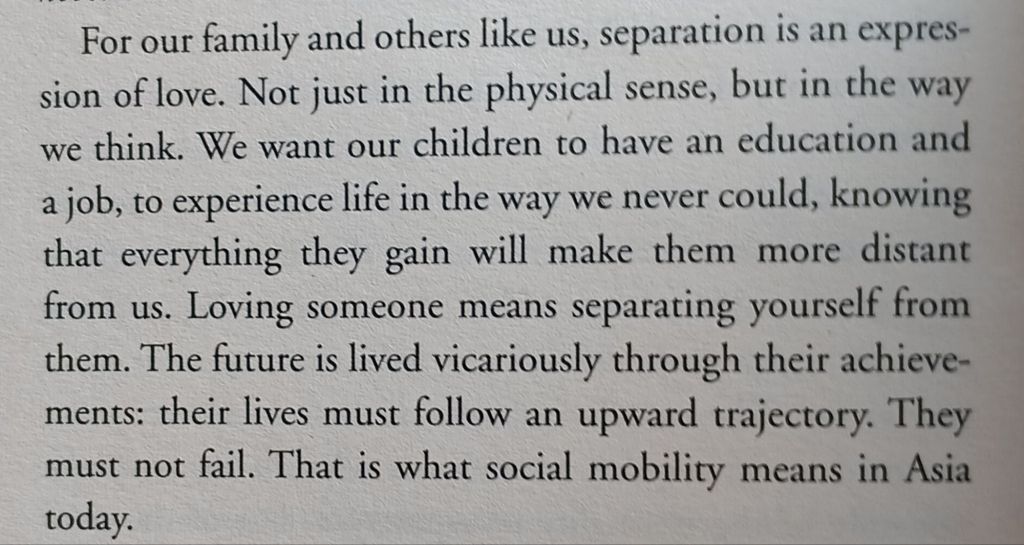

This is why, I believe, Tash Aw characterises the function of familial estrangement – communion across distance (even perhaps elements of psychosocial distance – that is the reality, if not the ideology of Asiatic lives in his experience, reinterpreting that great link in attachment theory, the control of ‘separation anxiety‘:

To love is here to accept that the person you love will become ‘more distant from us’ and to love that person in their emergent change. In a sense that is what Bowlby meany in inventing the cognitive model of self as the lynchpin of attachment relations, though never would he have endorsed Aw’s ‘separation is an expression of love’ except as an outcome of healthy development as an adult and only when one is an adult. This is why the theory tends to back conservative options in family policy and ideologies of what a successful family should be.

When Aw says that he believed his 2021 text may be harsher than that of 2016, it is likely that he was accounting there for some of the effects of an ideology of entitled belonging in white Brits, like those intent on talking parties of their friends on walks, and taking the opportunity as one white man, who lived in ‘the country’ (in Gloucestershire though it was not his native county) when he was not operating as a London lawyer, to say: ‘I know it sounds weird, but at a time like this I really feel attached to the land‘. [5]

Similarly Tash Aw takes aim at white British students who near the end of university courses ‘announced they were going to be writers’. The reason for their confidence and entitlement turned out to be that it was supported – financially, emotionally and existentially – by parents who were rich and successful and sometimes ‘even successful writers themselves’. Aw found that he needed to attend a course to ‘figure out ways to mould my desire to write into that magical state of becoming a writer’. And what does he learn – always to write at a distance from himself and his own experience and that of his enforced separations. It is a kind of trap that eradicates authentic narration of migrant experience, of that alien to entitled and ‘well-known’ writers. [6]

This is a beautiful book but I would urge that you read it to gauge just how far Tash Aw moved from thev person he is in this book to the model of love, attachments and desire in The South.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxx

________________________________________________

[1] Tash Aw (2021: 90) Strangers on A Pier: Portrait of A Family London, 4th Estate.

[2] Petrina Fernandez (2021) ‘Tash Aw’s expanded ‘Strangers on a Pier’ explores love of family and country’ in Options [online] (16 September 2021 – 8:59am) Available at: https://www.optionstheedge.com/topic/culture/tash-aw%E2%80%99s-expanded-strangers-pier-explores-love-family-and-country

[3] Tash Aw op.cit: 87f.

[4] ibid: 6

[5] ibid: 80

[6[ ibid: 75f.