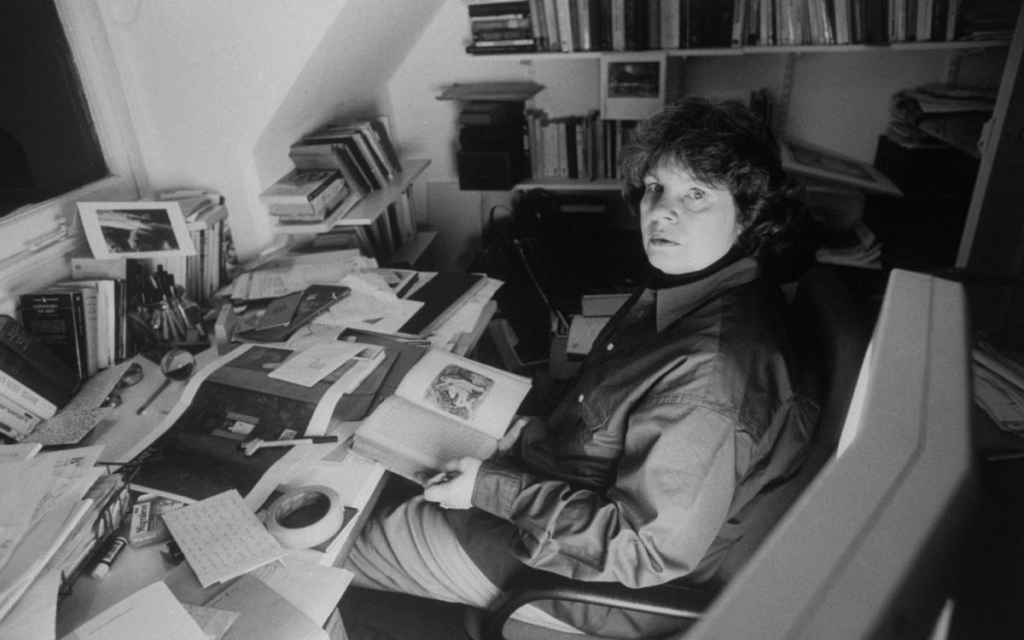

In her mid-career (in 1990), the mow deceased novelist A.S. Byatt wrote a novel called Possession. This novel attempted to bring together people whose actions running in parallel between two centuries learn about the values that gather around the term posession. to do so Byatt called on most of the meanings that the word ‘posession’ has in our culture – here listed from Mirriam-Webster:

possession (noun)

1 (a) : the act of having or taking into control; (b) : control or occupancy of property without regard to ownership; (c) : ownership (d) : control of the ball or puck, also : an instance of having such control (as in football) – “scored on their first two possessions“.

2 : something owned, occupied, or controlled : property

3 : (a) : domination by something (such as an evil spirit, a passion, or an idea); (b) : a psychological state in which an individual’s normal personality is replaced by another; (c) : self-possession.

In the novel characters fight for possession of a series of love letters that reveal the passion of two Victorian poets (based on the Barrett-Browning alliance), confronting every which way one can be possessed and the difiificulty of defining good and evil in the desire for and achievement of such possession

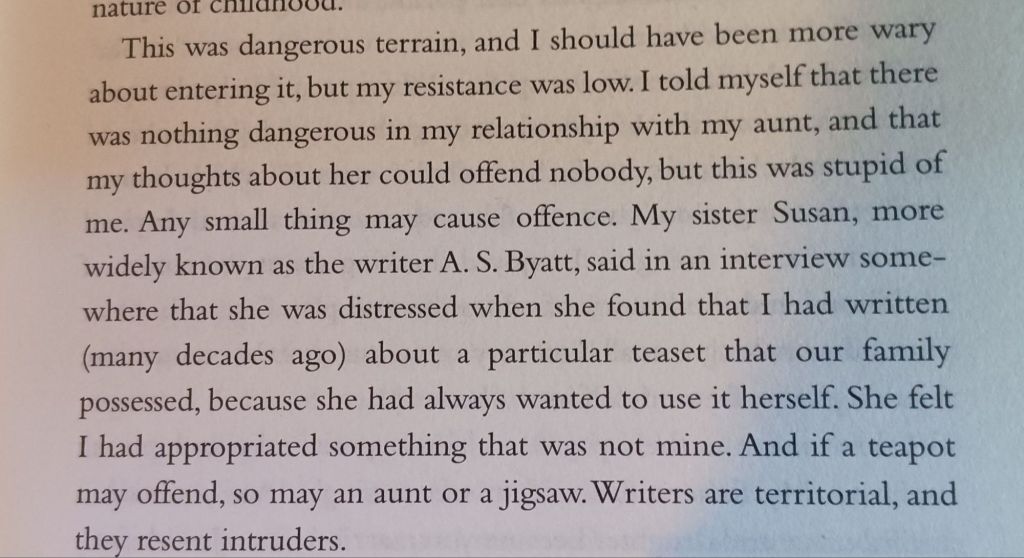

My own passion for books has many causes – but some (at least) of it came from knowing and being taught by A,S, Byatt, known to us as Mrs Duffy. I have thought of this word as I try everyday to dispossess myself of books I have. Only duplicates went from my Byatt collection and not even those when i could justify differences in the editions that were not merely related to any imposed editorial and critical apparatus in any particular edition. Yesterday I turned to my likewise complete collection of her sister’s novels, Margaret Drabble. In the end many have now gone from this collectio, although not particular favourites and the early ones. Why did I become less possessive over these books as memories of the joy of their early reading. I think because whilst thinking about them I turned to Drabble’s The Pattern in the Carpet: A Personal history With Jigsaws and read in her preface about the difficulty she had defining the project in her work. It based based on reflections on jigsaw work that she found therapeutic for her enduring depression (an issue with both sisters) and the aunt who introduced her to them. In that sense it requires some autobiographical reflection on her childhood and family. Here, though, she thought she might encounter monsters – and ones related to whose memories these were which she would attempt to own in the book. She says:

There is clearly history as well as projected fear in these words – Drabble’s early novels did include female protagonists whose ordinary and everyday lives were overlooked by fearsome over-intellectual and intellectualising sisters and Byatt’s second novel, The Game, reversed the process having one sister who wrote popular novels but who was rather less than cautious about treading on common family experiences in her novels and a fearsome possessed academic sister with fantasies about snakes and a rather intellectualised form of original sin.

The cover of the American first edition of The Game.

Drabble’s version of the competition between the sisters takes the form of Susan’s anger (her first name was originally Susan and Byatt was furious when her American publishers translated her name on the American first edition of one of her novels to ‘Antonia Susan’. Susan, she thought, was not their possession to use, any more than her sister had right to use a memory of a tea-set that she coveted to use. The family possessed it but did either daughter have the right of possession after their parents’ death. The problem with possession, even by family memories, is that they distort identity into forms that are intrinsically about competitions over possession.

Who, even, has the most right to be possessed by the passion or spirit of those memories. That competition extended to the sisters’ lives as champions of literature. Drabble wrote a wonderful biography of the queer novelist and short story writer Angus Wilson, her friend. Byatt when commissioned to compile the Oxford Book of Short Stories took great pains to announce that Wilson was not fit to enter her anthology of English Short Stories, and mocked the literary establishment that did so – as she later did with J.K. Rowling (in the latter case quite rightly in my view).

Possession is not just nine-tenths of the law of ownership, it is also the rationale of competitive self-possession. We refuse any hold on ourselves by others but in doing so render ourself a sterile non-negotiable concept, a being that spends all its energies and wastes its emotion in defying imagined incursions into our space. The truth is, I suppose, that there is no personal space that is indefatigably ours – at least we think that about other people’s claims. In global realpolitik neither Ukraine nor Palestine will be allowed to define itself because in Trump’s words, ‘they have not the right cards on the table’. If might is right, possession is the starting point of legal settlement. Trump even imagines creating luxury golf-courses and Florida-like beach resorts for the global rich in Gaza, so that people might holiday, even those in the 51st state of Canada.

The upshot of this however is possibly that Byatt was right to contest who owned imaginative right to a tea-set for it is these rights which determine self assertion. However, to turn to global war over precedence is right when no-one does it, as the bad’ characters of Possession learn. But Byatt is the greater artist of course without doubt, and even in her death that remains clear.

Back then to dispossession of my library. Below is the storage of books I have sadly let out of my possession and which the compant The World of Books won’t give even their usual remittance of 20 pence each for. Clearly there is no market. I do not want to be influenced in my qualitative judgements by the market so I am glad I only learned this once I let them go. I let them go not because they aren’t great books to my mind but because to hold on to them merely because they mattered to you once is a sad business. It is a refusal to grow in your evaluations beyond initial judgements and decisions. These books may return to general appreciation but it will be a communal decision if they do and not yours.

That is a small enough step to my goal: “to learn how to rely neither on what I possess, or wish to possess, and hence no longer, perhaps, to be possessed“. But it’s a step. It will do as I move to accepting that final dispossession of all my worldly avatars of the world-spirit.

Bye for now, with love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxx