‘I’ve done worse things, things I am not proud of including standing here in the dark with David, I know there’s a little bit of hypocrisy there, there are shades of hypocrisy in everything. Our principles stretch like elastic bands’.[1] When certainties fail us, as they must in time, there may be no alternative to moral relativism, but Nicola Dinan shows us, in her novel Disappoint Me, that the fact that some, and perhaps all, human behaviour may be found to contain some small part, or even a thick stripe, of the immoral may have to be accepted as the ‘shading’ accompanying human actions and add to the flexibility of standards of moral judgement of self and others.

I have in the past blogged about Nicola Dinan’s startling debut novel, Bellies (see it at this link).Second novels are meant to disappoint but Disappoint Me does not disappoint me at all as a reader, though its effects are subtler. There is the same insistence that trans characters should not be treated as morally neutral, not only with regard to the main narrator of the two co-narrators of the story, Max, but also the character at the novel’s moral heart Alex (‘Just Alex’ she insists at one point to avoid accusation of passing as a cis woman.[2] The morality of all this is complicated precisely because Alex does – perhaps must do – that in order to survive in a ‘non-trans-world’. Nevertheless, Dinan shows that Alex is, to say the least, sexually very available to men regardless of their attitude to trans women without any hint of the ‘guilt’ Max proposes to herself in the same situation (indeed with the same men). Yet her punishment for not informing Fred that she is trans before sucking the ‘dick’ of that very heteronormative male Fred is not only excessive but grotesque in its visceral display of transphobic hate.[3]

Max’s faults are shades of this – her guilt is always available to her, even in flirting with the super-attractive David with whom she has been paired for the heteronormatively structured wedding march at a friend’s heterosexual wedding whilst still in a supposedly monogamous relationship with Vincent, although she stops short of accepting a threesome asking her lesbian friend, Simone, to be involved therein. But it matters to Dinan to place herself in the great tradition of the novel of the examined life (the same one perhaps that F.R. Leavis charted from the novels of Jane Austen to Joseph Conrad – of lifes and lifestyles seeking the ethical validation of their character’s (including narrator-characters’) actions and discourse. There is perhaps strong reasons why Dinan sees this project s valid. I will look at the first issue only but assume links to the other numbers in the list:

- First, the decay of the moral certainty provided by patriarchal religion (an old story of course and there is no need for the novel to return to Nietzsche top explore the base concepts) and (much more importantly, its substitutes in civil society – the family in particular, though the church in its civic role in births, marriage and deaths decoratively. See the lengths, for instance – none that convincing – by which ‘heterosexual couples’ do things at their weddings ‘to convince themselves they’re defying tradition’.[4]

- Second, the related passage of authority from value systems organised in binaries such as good and evil (or more simply good or bad, moral and immoral) especially in relation to judgements of behaviour expected to take into account the situation of the action taken and the actor taking it – not least in time, space and cultural diversities.

- Third, the reflection of the decay of binary thinking in other systems of categories of humankind – not just between bad and ‘good’ people but between white and non-white ‘racial’ cultures, heteronormative and non-heteronormative shaping of behaviour (this brilliantly satirised in Emily’s wedding), ‘gay’ and queer subcultures (discussed in terms of venues in which to meet in the novel) and male and female value systems. The bastion of reactionary thinking – reductive versions of the biology’ of sex/gender are a late one to fall , or be pushed, under the bus of history. However, in this novel the crux of the moral issue lies in the existence of expectations of negotiations of cross-evaluation between cis and trans persons.[5]

- Finally, the constant interaction between seeing relationships teetering between involving more than a couple – not only in the wished for threesome sought by David and his like in the novel but also in crosses of interest such as those Vincent supposes in seeing Alex ask Fred ‘questions that triangulate us’.[6] The most interesting triangulation is probably Aisha’s where the third person in the relationship conducts his affair with her by both of them meeting only in mutual sight masturbating simultaneously in a windows in their separate flats that face each other.[7]

Let’s consider the novel’s treatment of the patriarchal tradition. Whilst most characters remain remote from that tradition conceptually relationships with sick fathers oft predominate, and even take predominance over some aspects of mother-child relationships. Even men who resist the shaping of the selves in heteronormative patriarchy struggle, and this is surely Jamie’s role in the novel – both in terms of his alienation, like Max’s, with his alcoholic father, and his wish to keep the ideological role of father to his child in his own life with little or no care for the mother of his baby. He has no ‘time for a relationship’ with girlfriend Maria and though he claims, after they split that ‘we’ are pregnant’, his role is less than thought through in that respect and also given too little ‘time’. It leads to their/her child being aborted by Maria. Men in this novel are often cemented mainly by complexly circumstanced (involving race as well as sex/gender and straight/queer issues) comparative ’dick’-quality-consciousness. Dinan must have laughed aloud when she created the joking thought of Vincent thinking about telling Alex, at this point though – as far as we know – though to be a cis woman, ‘about Foot-Long Wong but it feels weird putting the foot long in her mind’.[8]

But from being far in the background, Max’s father surges to the forefront of the book’s stage when Max is unable to talk effectively to her mother, It is with her father – a kind of patriarch restored – that she discusses both the morality of relationships across male cis/female trans boundaries. For Max, the issue of Vincent’s bad behaviour to a trans girl in 2012 (‘outing’ her without her permission and then abandoning his commitment to her without notice – as a friend and possible lover- when she goes into hospital for ‘Bottom Surgery’. The latter moral failing is so much worse that it is bottom and not top surgery, max believes and yet this is an issue only to emerge into consciousness with the greater social consciousness of trans / cis distinctions. Max’s Dad understands little, Max believes., of these issues and for her has always being summed up as an absent, as well as alcoholic, father.

Dad has become known to her brother Jamie, and her friends as the man who ‘nearly set’ her ‘house on fire’ in a drunken session.[9] Her trauma still persists right to the end of the novel, when she apologises for telling others of her father’s lapse and collapses in his arms for him to ‘hold her in a way that is foreign and familiar’. There seems a need to recognise that in the passage of time the handling of the issue requires mutual forgiveness as well as mutual desire for a restoration of something long lost. One part of this is Max’s consciousness is that not for her to ‘punish’ him at all, for he does that to himself. And with that comes moral comparison:

I forgot how often I feel like there is so much bad inside me. How heavy mistakes and inadequacy sit on my shoulders. I’m sorry. To Dad. To me.[10]

In truth this scene is the reflected image of a much more important one where it is to her father, over a cigarette she cannot allow herself to smoke so soon before surgery. Max feels morally split about the fault that resided in her break-up with Vincent and the right she has to punish him for a failing he committed 11 years before – as a boy really – with little or no effective consciousness of trans issues or of how and when moral empathy should over-ride mere inability to understand the nature of the mix of contradictory elements in the characters of others. The discussion is long and I represent it below with may important omissions – particularly of evidence as its excellence as dialogue in a realist novel. Dad insists that her moral judgement lacks nuance (both the light and shade surrounding the actions of others – even his own), and, in that sense is too like her brother Jamie’s manner of dealing with things:

But if I don’t want to be like Jamie, then I have to forgive, be a little less righteous, which takes me towards Vincent, and that is, whatever I do, at odds with what I feel to be moral, but moral to whom? Good for what?

…/ Dad stops to look up at the sky again, /…/

“Maybe that’s more about acceptance,” he says, setting off again.

… / “You’re allowed to have time.”/ …

We walk on in silence. I feel like a child. A child fumbling with adult problems. …/

”People punish themselves”, he says.

I don’t respond, though I wonder whom he’s referring to. Me. Vincent. Himself. …’.[11]

This provides the framework for the two persons to forgive each other, and with time for Max to learn to forgive Max, and perhaps, even the more problematic Fred, for both have matured in eleven years – both are in different circumstances in other respects than age. And Max has, from the start, allowed us to see that it is a binary error itself to invalidate the possibility that trans people may behave badly, that in this their differences, as well as similarities – of experience for instance – to each other matter too. Early in the novel she differentiates her trans acquaintance Carla from herself, accepting that Carla can be roughly violent in contact and rude to others. The comparison brings forth one of the novel’s excellently complex short sentences: ‘Our skin contact is feigned closeness through shared experience’.[12] In the 2012 sections of the novel however, most people (even those supposedly empathetic) know even how to name trans people.[13] And on top of this, they confuse people with their ‘parts’ as both Fred, and to some extent Alex, do and confuse jealous self-interest with aiming to do what it is ‘the right thing to do’.[14] But in 2023, even Simone, a lesbian feminist, struggles to express how and under what labels she knows Max as a response to the latter’s ‘transitioning’ and how that might differ to other changes in people over time.[15] In the brave new world of each rediscovery of the range of persons in life, everyone (even readers I suggest) is like Max in her past-quoted-conversation with her Dad, able to say: ‘I feel like a child. A child fumbling with adult problems’. Perhaps in history we all regress to the ethical novicehood of children wondering what adult behaviour means and, indeed, how, in truth, adults differ from children as ethical agents WHEN THEY DO INDEED DIFFER – as in Henry James’ What Maisie Knew.

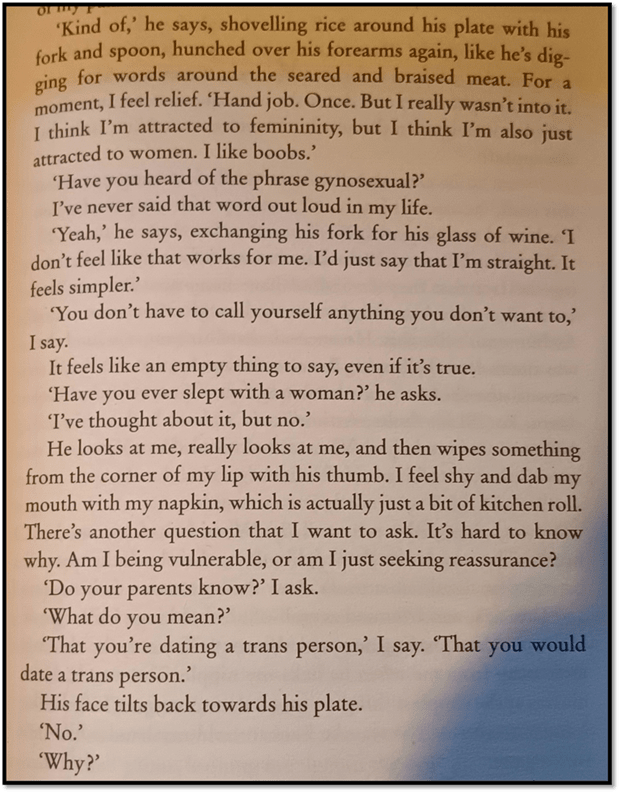

Much of the moral issue in the book is I think take up with evasions of the truth of the situations to which we apply ethical judgement. A favourite passage of mine – for the skill of its dialogue as well as its subterranean guiding wisdom, is that where Vincent struggles to understand his own sexual attractions in the light of Max’s own struggle to know through what questions she might test Vincent’s moral fibre in maintain relationships, after Vincent says that: “It’s hard to believe you’re trans sometimes’., which though recognised as a ‘gaffe’ disappoints Max, that disappointment fostering the novel’s title. But how can you test the durability of cis-trans relationships in the light of the errors of perception which guide people’s views of each other. Max tries by asking Vincent: “Have you ever slept with a man?’

Vincent cutely replies in another fine passage in its handling of the metaphors for mutual consciousness and joke filled meta-reference to its own subject-matter:

My photograph of detail from Nicola Dinan (2025: 49) ‘Disappoint Me’ London, Doubleday

As well as a wonderful; example of a conversation that steers away as well as into its subject, the stage business is exemplary – again using food complexly as does Bellies. The interrogation is not unlike that by Lady Bracknell of Jack Worthing in The Importance of Being Earnest, except that Max unlike Lady Bracknell seeks reassurance not only about the acceptability of a suitor for her daughter but of her own vulnerabilities as well as the suitor’s in terms of her lack of certainties about what kind of proposition she represents to Vincent – a man in transit or -? The same questions Max asks, the reader asks. There is more than coincidence in the fact that both the women he loves in the book are trans, whatever the state of his knowledge about them. The base question iun the passage is: Is it true that ‘you don’t have to call yourself anything if you don’t want to’, for that is the crime Fred punishes Alex for. Max’s play for the word ‘gynosexual’ is almost comic in its inadequacy, despite the accuracy of Max’s use of it – for the love object of the gynosexual does not have to be a woman but only to have female parts.

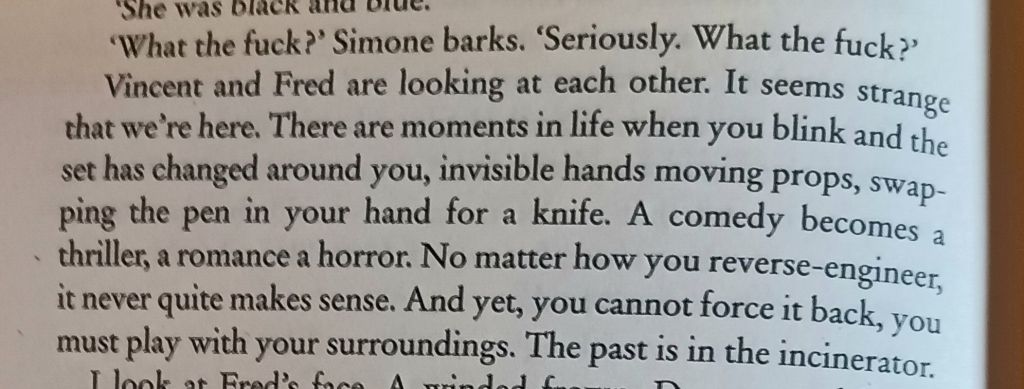

This novel is a joy and never a disappointment, whatever the reason you as a reader read. Much of it is about writing and reading and there is enough there to constitute a bog of its own.[16] But, for me, the delight of Dinan as a writer is her command of so many skills in which I like the writers I read to excel. And incidentally let’s end with one that emphasises the meta-theatricality of her method (which recalls the use of theatre in Bellies too). In a morally central 2023 scene of the novel, Vincent reveals that in bed he could hear the conversation between Max and Fred outside. We suspect that his jealousy (of Fred or Max) matches that under-explored jealousy of Fred or Alex in 2012). What is clear is that drama that follows is not about what men think about women but what they think, feel and want to do with each other – where a ‘triangulation’ of persons (Max, Fred, Vincent) turns back to a binary but not based on sex/ gender (Fred/Vincent) if certainly based on sex. The metaphoric framework is theatrical, and Max is not participating actor but audience, feeling the full force of the fourth wall of the scene disintegrating in front of her’

My photograph of detail from Nicola Dinan (2025: 224) ‘Disappoint Me’ London, Doubleday

What tells when you read carefully is the presence in the passage of a ‘pen’ for it betrays that Max as a writer is the source of the violence seen in the drama between two men and that she is as aware of bearing either of these phallic symbols as her reduction to the passivity of an audience to action she in fact generates. You cannot ‘reverse-engineer’ any of that easily but if you could some of the psychodynamic core here of the book would make great sense, I think. Or I wonder!

Do read it!

With Love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Nicola Dinan (2025: 245) Disappoint Me London, Doubleday

[2] Ibid: 37

[3] Fred sees Alex negatively as a ‘cock-teaser’ because she sucks his dick but allows no further sexual exploration, but is in a rage when told Alex is ‘trans’ by Vincent (ibid: 171f.)

[4] Ibid: 239

[5] See, as examples only, respectively, ‘race’ refracted through values based on male consciousness of the meaning of their ‘dick’ length (31), heteronormative and gay morals on befriending an ‘ex’ (98f.) or the wedding with its heteronormative rituals imposed on LGBTQI+ people (236), The acceptability of ‘gay’ versus ‘queer’ values in venues (7) , for discussions of the meaning and value of having sex with someone of the same sex/gender (49) or whether ‘gay’ top/bottom binaries match male/female ones (60), and trans/cis value systems compared – regarding possible dress codes (117) and with response to the relative morality of leaving a trans persons to suffer alone the after-effects of ‘bottom’ surgery, meaning surgery transformative of genital parts (227).

[6] Ibid, respectively: 246, 129.

[7] Ibid: 136

[8] Ibid: 37 Foot-Long is a racial counter-stereotype created by Fred to reference his belief in short-dicked Asian men and also referencing Vincent’s school nickname by the white boys there: ‘Vincent Ching-Chong’.

[9] Ibid: 114

[10] Ibid: 261

[11] ibid: 255f.

[12] Ibid: 4

[13] Ibid: 35

[14] Ibid: 175f.

[15] Ibid: 56

[16] Some page references if you are interested: ibid: 7, 12, 13f., 29, 58, etc.