They say retirement's a time for leisure

But not necessarily for pleasure.

The little iambic couplet I composed, with obligatory soft and feminine rhymes (don’t blame me though for the sexist nomenclature of the discourse of poetic technique where double rhymes are named both feminine and weak), for this sad blog is meant to look at how the time that comes upon you in retirement can feel burdensome – leisure without pleasure, too often harking back to a better past that cannot be restored. We living an age where it is ultra-dig to claim that ‘personally, I have no time for leisure’ and, as a result, the pursuit of monetary income and the growth of this fluid asset pool at all costs – to self (the pains that involves oft come much later and can be ignored) or to character – takes precedent over all other priorities. The discourse of support for ‘working people’ is now the common discourse of the right (who usually use it support unearned income on inherited or capital assets) and the modern Labour Party. it;s a language that pretends that some work for their living and others are burdensome in their dependence in ways that are worthy(for so it goes people cannot be blamed for their disabilities unless we can prove it was their fault – hence the stress in this early government of rooting out obesity) or unworthy. How soon we have returned to the language of Utilitarianism. But even the ‘worthy poor’ must accept they are a burden in this way of seeing things and live with the self-perception necessarily involved, with gratitude for their benefactors. It is likely that early retirement without provision for a long period of economic inactivity of unearned income with be similarly looked at soon.

The discourses of ‘retirement’ in past ages are heavily reliant on the model provided by the Roman state, where service actually meant service to the state for Rome, like the earlier period of Ancient Greek European hegemony, afforded luxurious leisure time during that service because the tasks of everyday living could be devolved – to slaves and the dependent poor. The retirement Virgil praised in the Golden Age of Augustus was retirement from public service, often military service, the State and the City to a country estate. It is the dream of the first of the Gladiator films – running one’s finger through the buxom ears of corn whose growth and care was safely handled by those working for you.

In later more modest times the care, which really meant governance of care – care is after all hard work, that filled retired leisure time oft became a garden’s limits rather than a sprawling estate. This transition was marked in England in the Civil War of the seventeenth century, where men laid up arms that they had used in the defence of the People against the squalid excess of monarchy and arrogant self-obsessed aristocracy – or so the ideology seems to suggest if not the historical reality. Retirement meant then what it should from its etymology in military terms (when an army falls back – perhaps only to recoup from the battle field and its use thereafter by analogy in the theatre, in Shakespeare’s Globe for instance, ‘retire’ is to leave the public stage for the tiring-houses behind it, withdrawing from the public and visible. In each case retirement is a confuted with reflective time.

Poets were especially aware of this. The classic retirement from public politics was John Milton. though too humble to retire to estate he had no garden but one he could built in his mind into which to retire – the Garden of Eden he made, to watch it destroyed by human pride (as in the Civil War he might have reflected that led to a not-so-glorious Restoration of a Philistine horde of Stuart monarchs) is probably the most carefully worked for Garden for reflection in epic literature. But the famous poet of retirement in Gardens was his friend Andrew Marvell, a man less marked as a supporter of ‘regicide’ as Milton for the latter had signed Charles I’s death=-warrant.

Marvell’s Garden poems were associated with the patronage of the hero if the Civil War, Thomas Fairfax, once the most acclaimed leader until eclipsed by Oliver Cromwell, and then canny enough to serve even under restored monarchy, though in retirement for his last 11 years in his Yorkshire estate at Nun Appleton Priory, a convent turned into country-house.

The young General Fairfax

Marvell’s mosrt famous poem grew from retired refection on this man’s life and its meaning, and, of course, of his tutorial care of his daughter, Mary (called Maria in the poem) Fairfax. The germ of his greatest poem The Garden was a long eclogue, somewhat based on Virgil’s models of pastoral Upon Appleton House of 1651. Within that long poem, Marvell pored over every meaning of ‘retirement’, ‘leisure’ and ‘pleasure’ that he could – enough to condemn the nuns of the original abbey whom he portrayed as predatory lesbians for their Romish (Catholic) indulgences, but enough to praise the humble retirement of Fairfax, who might have chosen, from his significance to the English Protestant state a much larger place of retirement – though the poem somewhat exaggerates the humility of the Generals retirement home, substituting humility of architectural pretension for a home not made by a ‘foreign architect’:

Within this sober Frame expect

Work of no Forrain Architect;

That unto Caves the Quarries drew,

And Forrests did to Pastures hew;

Who of his great Design in pain

Did for a Model vault his Brain,

Whose Columnes should so high be rais'd

To arch the Brows that on them gaz'd.

Why should of all thing Man unrul'd

Such unproportion'd dwellings build?

The Beasts are by their Denns exprest;

And Birds contrive an equal Nest;

The low roof' Tortoises do dwell

In cases fit of Tortoise-shell:

No Creature loves an empty space;

Their Bodies measure out their Place.

But He, superfluously spread,

Demands more room alive then dead.

And in his hollow Palace goes

Where Winds as he themselves may lose,

What need of all this Marble Crust

T'impark the wanton Mote of Dust,

That thinks by Breadth the World t'unite

Though the first Builders fail'd in height?

But all things are composed here

Like Nature, orderly and near:

In which we the Dimensions find

Of that more sober Age and Mind,

When larger sized Men did stoop

To enter at a narrow loop;

As practising, in doors so strait,

To strain themselves through Heavens Gate.

And surely when the after Age

Shall hither come in Pilgrimage,

These sacred Places to adore,

By Vere and Fairfax trod before,

Men will dispute how their Extent

Within such dwarfish Confines went:

And some will smile at this, as well

As Romulus his Bee-like Cell.

Humility alone designs

Those short but admirable Lines,

By which, ungirt and unconstrain'd,

Things greater are in less contain'd.

Let others vainly strive t'immure

The Circle in the Quadrature!

These holy Mathematicks can

In ev'ry Figure equal Man

Nun Appleton House and its Gardens become in Upon Appleton House , the very model of the modest ‘composition’ of a home, life and character, and. of course, of the English art used to compose a poem. When Wordsworth used the double meaning in the word ‘composed’ to reflect not only a poet’s creativity but a state of mind in his poem on the ruins of Tintern Abbey, he merely followed Marvell, if, it has to be said, less showily for a poem about a poem about ’emotion recollected in tranquility’: Lines Composed Above Tintern Abbey (of course the word ‘composed’ was only substituted for ‘written’ as Wordsworth retired fro a belief in radical simplicity). Here is Marvell praising leisure from labour, and public show, and even (to get his own life as a poet (who seek – the bays’ or the laurel wreath) in, from the arduous praise of the love of women. His Garden of Eden, it should be noted is one where men are untroubled by women. This modestly proportioned path is the path he suggest to Heaven itself:

But all things are composed here

Like Nature, orderly and near:

In which we the Dimensions find

Of that more sober Age and Mind,

When larger sized Men did stoop

To enter at a narrow loop;

As practising, in doors so strait,

To strain themselves through Heavens Gate.

Even if men are ‘larger’ than life, they may stoop to enter the heaven described in Scripture ass antagonistic to worldly rich men – has anyone told Donald Trump and Elon Musk – (Matthew 19, verse 24): And again I say unto you, It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God. This poem even tries to reconcile the aristocratic lifestyle Fairfax attained to his knowledge of a more democratic polity in the Civil War when even the voice of Communist Levellers were heard, if ignored:

For to this naked equal Flat,

Which Levellers take Pattern at,

The Villagers in common chase

Their Cattle, which it closer rase;

And what below the Sithe increast

Is pincht yet nearer by the Beast.

Of course, Marvell does what he can to level the Levellers as being ‘pincht’ (pinched) and lacking generosity n their ideals(unlike Fairfax who opened meadows to grazing in common for local villagers he seems to ssay) but he did include them. just as the ideals of the Garden of Eden to Milton were socialist ones, adapted only by the Fall of Man. Everything is modest in Marvell’s older retired (but for a bit of tutoring) age – the sober Age and Mind in Englands follows a bloody revolution and bloody tyranny under Cromwell given in each case the cause of protection of the English people but it is aligned with the sober age and mind of Marvell no longer anything but composed in his verses. At least so he says. However, Marvell’s retirement may have given im leisure, as it did Fairfax in the governance of a beautiful garden estate but it did not mean that all his leisure was pleasure. This is clear in the long length of Upon Appleton House, where the Mower Damon cuts himself with his own scythe (‘the Mower mown’) and this becomes an image of time in revolt at least – for that icon too holds a scythe proving to humans that ‘all flesh is grass’.

in Marvell’s greatest poem, the longueurs of reading (for some – cos I love it) Upon Appleton House is reduced to a briefer poem on retirement from the pursuit of achievement – in which retirement is a life indeed of leisure (or in his term ‘repose’) where goals of social fame are given up for ‘delicious solitude’. No poem in English, except for Paradise Lost, so well conveys the sensual and fleshy feel of solitude, though the plants’ tempting sensuality is continually nailed down by pretending they are allegories of ‘Quiet’ and ‘Innocence’. It’s a masque because if, amongst the things Marvell has renounced is the pursuit of women so philosophically reflected in that poem about urging a women to have sex, To His Coy Mistress, the colours of The Garden are ‘more am’rous’ yet if enjoyed in an entirely masturbatory way. His models of the am’rous are of course models of rape foiled by the metamorphosis of the pursued into a ‘plant’ such as you might find in a garden – Daphne into laurel, and hence the bays worn by Apollo and future poets in his name – and Syrinx into a kind of ‘reed’. Anyway, read the whole poem again!

How vainly men themselves amaze To win the palm, the oak, or bays, And their uncessant labours see Crown’d from some single herb or tree, Whose short and narrow verged shade Does prudently their toils upbraid; While all flow’rs and all trees do close To weave the garlands of repose. Fair Quiet, have I found thee here, And Innocence, thy sister dear! Mistaken long, I sought you then In busy companies of men; Your sacred plants, if here below, Only among the plants will grow. Society is all but rude, To this delicious solitude. No white nor red was ever seen So am’rous as this lovely green. Fond lovers, cruel as their flame, Cut in these trees their mistress’ name; Little, alas, they know or heed How far these beauties hers exceed! Fair trees! wheres’e’er your barks I wound, No name shall but your own be found. When we have run our passion’s heat, Love hither makes his best retreat. The gods, that mortal beauty chase, Still in a tree did end their race: Apollo hunted Daphne so, Only that she might laurel grow; And Pan did after Syrinx speed, Not as a nymph, but for a reed. What wond’rous life in this I lead! Ripe apples drop about my head; The luscious clusters of the vine Upon my mouth do crush their wine; The nectarine and curious peach Into my hands themselves do reach; Stumbling on melons as I pass, Ensnar’d with flow’rs, I fall on grass. Meanwhile the mind, from pleasure less, Withdraws into its happiness; The mind, that ocean where each kind Does straight its own resemblance find, Yet it creates, transcending these, Far other worlds, and other seas; Annihilating all that’s made To a green thought in a green shade. Here at the fountain’s sliding foot, Or at some fruit tree’s mossy root, Casting the body’s vest aside, My soul into the boughs does glide; There like a bird it sits and sings, Then whets, and combs its silver wings; And, till prepar’d for longer flight, Waves in its plumes the various light. Such was that happy garden-state, While man there walk’d without a mate; After a place so pure and sweet, What other help could yet be meet! But ’twas beyond a mortal’s share To wander solitary there: Two paradises ’twere in one To live in paradise alone. How well the skillful gard’ner drew Of flow’rs and herbs this dial new, Where from above the milder sun Does through a fragrant zodiac run; And as it works, th’ industrious bee Computes its time as well as we. How could such sweet and wholesome hours Be reckon’d but with herbs and flow’rs!

This Eden is retired (but is also masturbatory) because it is precisely a ‘happy garden-state’ because ‘man there walk’d without a mate’, or indeed perhaps wanting, desiring or needing one. Time is there – in the form of a sundial fashioned to bear flowers . He wants to persuade us that his time is a pleasurable peaceful thing composed of ‘sweet and wholseome flow’rs’. But gardens are wont to include a serpent or two -Marvell says so in Upon Appleton House.

I The Garden, the fallen state of humankind is there but only as a reminder that even retired folks, even those ensconced in gardening activity, can suffer falls – minor and major, and the idea of unstained pleasure is impossible. Look again at these crucial stanza:

What wond’rous life in this I lead!

Ripe apples drop about my head;

The luscious clusters of the vine

Upon my mouth do crush their wine;

The nectarine and curious peach

Into my hands themselves do reach;

Stumbling on melons as I pass,

Ensnar’d with flow’rs, I fall on grass.

Meanwhile the mind, from pleasure less,

Withdraws into its happiness;

The mind, that ocean where each kind

Does straight its own resemblance find,

Yet it creates, transcending these,

Far other worlds, and other seas;

Annihilating all that’s made

To a green thought in a green shade.

They are more sensual than ever, even start being so as ‘apples’ (the bearer of Original Sin and the Fall in Eden. they are only prefereable to a mate because they enact a mate’s sensual approach – in kisses that have too much pressure to be innocent of further intent. Even ‘flow’rs’ ensnare the lyricist whateveer professions hec makes of having sex with with the rest of worldly pleasures that involve other people. To ‘fall on grass’ echoes not only the Fall of Man but its meaning – the memory that, having fallen, ‘All fleshe is grass‘ ( Old Testament book of Isaiah, chapter 40, verses 6–8, available to read at the link) and that death, sin and collusion with evil is present.

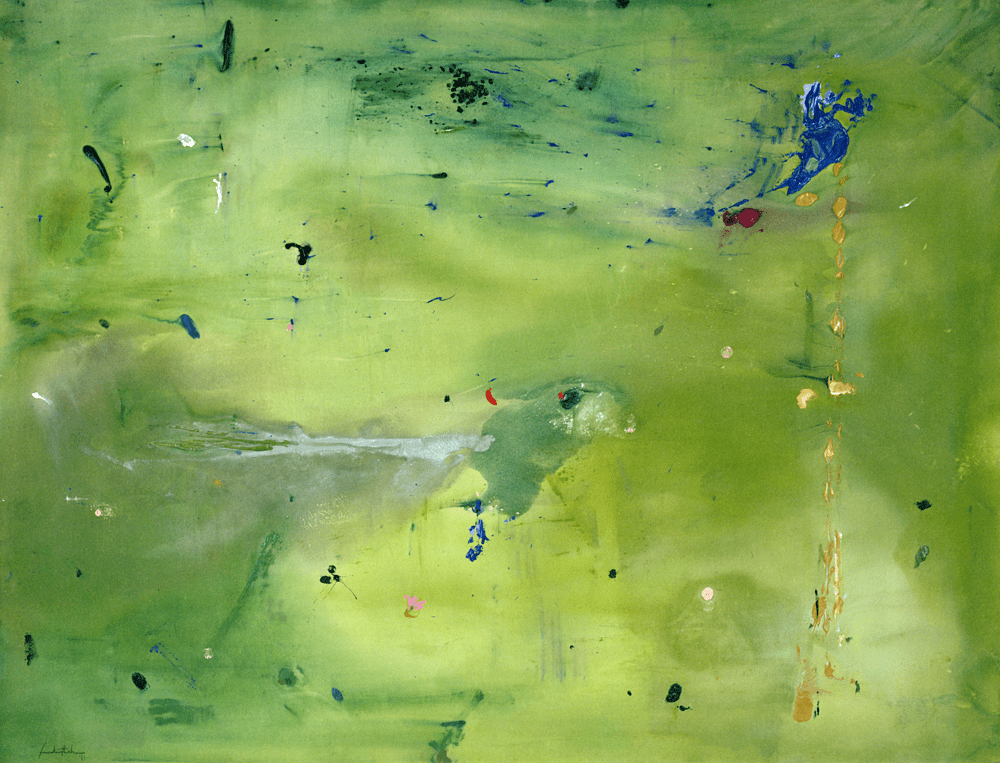

So even at leisure, no pleasure is guaranteed to the lyricist. His retirement becomes even more an interior retirement or ‘withdrawal’, where he might drown in the ‘ocean’ that is his inner ‘mind’. People have always though how beautiful are the lines that follow and how often recalled by people who feel the shade striking through the green leaves of their shade under a tree, but they are also – and hence their beauty in my view – because they embody in the principle of creative beauty, like Shelley later in The Ode to the West Wind,both the principles of creation and DESTRUCTION. But more fearsome than Shelley: In Marvel ‘all that’s made’ is not just destroyed (a strong world) but is felt in its ‘Annihilating‘ by the process. I shudder as I smile in contemplating not only non-existence but the state of never having existed, the never having been born Ancient Greek tragedians believed to be the happiest state of human aspiration. Do I see something like Helen Frankenthaler sees in her 1981 image of global destruction that uses those words?

So to the prompt question. My couplet is enough if you resist the challenge of the real poetry of Marvell, but iots point is to say that the idea of enjoying ones leisure is an illusory one, unless retirement is entirely non-reflective. For me to retire is necessarily to retire within oneself not seek pleasure: “Meanwhile the mind, from pleasure less, / Withdraws into its happiness’. These lines can be read lazily or otherwise for obviously no longer trusting in pleasure as a means of looking for ‘happiness’ seeks it within the need to question and penetrate the state of ‘happiness’ itself. The results are never straightforward – for happiness is an emergent not an absolute quality, unlike ‘pleasure’, and involves processes too complex, and deeply interior to be merely pleasurable or ‘enjoyable’ to use the blander term of the prompt – though JOY definitely is not bland but can be in some formulations of it, as with what some mean by happiness, like Ken Dodd (see my blog on that). That is why I say then:

They say retirement's a time for leisure

But not necessarily for pleasure.

‘All my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx