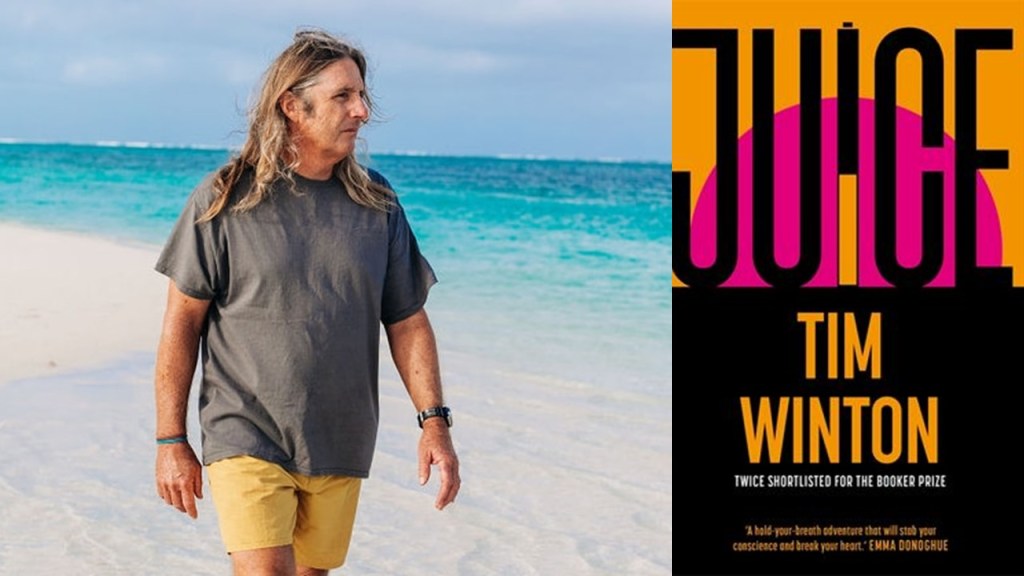

Of a ‘chert the size of an olive pit’, that travels with the narrator through the spaces and times of the novel Juice [2024] by Tim Winton, the narrator says that ‘… a stone is an expression of the earth, a signal of time. But it’s also a relic of experience. A thing propelled into the world. Dragging its past like an afterglow. And it’s just a rock, but its journey isn’t over, and neither is its destiny fixed’. In the dystopia imagined by Tim Winton whether destiny is fixed or not at any point in the globe’s political and environmental history is the central problem of the novel.

Occasionally you come across a review of a novel that says a lot of what you had to say and covers the notes you made about the novel, thus I recommend that by Paul Giles in The Australian Book Review (linked here). He says much of what I wanted to say about the metaphor of ‘juice’ in the novel thus:

Winton’s hero recalls how, after learning about ‘the empire that poisoned the air and curdled the seas’, he embarked willingly on a series of violent missions to root out the ‘bloodlines and networks’ that lingered even after the death of their nefarious empire. Oil companies and ‘faceless corporations’ are particularly in the firing line here, and human ‘objects’ are ‘acquitted’ in a ruthless, impersonal manner, with the old soldier declaring he had no compunction in dispatching ‘a man whose class and trade and prodigious inheritance had helped asphyxiate half of life on earth’. The ‘juice’ of the title is thus presented not only as a colloquial term for the energy produced by oil companies – the companies had ‘every sort of juice. The stuff that drove engines, trade, empire’ – but also the energy that drives the hero’s motivation and resilience, his ‘moral courage’, as the author described it in a recent interview. ‘It takes a lot of juice to perform,’ his fictional counterpart observes. [1]

I do not know how Winton in the unreferenced interview referred to by Giles uses the term ‘moral courage’ but in my reading of the novel it may assume far too much of a positive evaluation of what Winton’s hero-narrator means by ‘performance’, which bears a great deal of the notion of the theatrical or deceptive ‘player’ (the thing he also was when Giles refers to him, using the novel, as ‘schooled in doubleness’). If you extend the quotation referred to by Giles it is clear that the energy is not so much the requirement of physical action (as a soldier and man) but as a actor/performer in front of an audience: ‘It takes a lot of juice to perform. For your comrades in the field, for the medicos in repat, and then for your loved ones in the aftermath”.

Of course Giles makes duplicity central to his review and his assessment of the narrator, which ends thus:

The protagonist describes himself as ‘a man schooled in doubleness’, and this extends beyond mere double-dealing in his personal affairs to encompass a wider sense of structural ambivalence. The narrative is interspersed with various excursions into the unconscious mind, with one rapturous dream transforming the narrator into a fish ‘swimming effortlessly’ in the sea along with ‘a million’ others, evoking an environmental idyll of collective utopia. Yet, in the final dream vision expounded in the book’s penultimate paragraph, the narrator cannot tell if ‘a constellation of hovering birds … were there to greet me or to peck me to pieces’. It is this sense of radical openness – ‘who can tell?’– that preserves a luminous quality in Winton’s mature aesthetic. In a 2013 interview, Winton remarked that ‘fiction isn’t a means of persuasion. Fiction doesn’t have answers. It’s a means of wondering, of imagining.’ Although the way it envisages climate catastrophe is thought-provoking, it is ultimately this creative projection of ‘wondering’ and uncertainty that makes Juice a profound as well as an enthralling novel.

As I read the novel, I think that – though I agree totally with the view of ‘doubleness’ as a feature of the writerly imagination, being, as it were, to imagine oneself or others one thing and another simultaneously, whilst entertaining too the fact that one’s fantasies can be interpreted themselves as having the double-edge of retributive threat as well as wish fulfillment – we cannot describe the novel’s view of ‘double-dealing’ as a less important than thus quality of its imagination. There is always temptation for literary readers to see the imagination as exempt from ideological service and, hence, carrying a kind of duplicity that belittles its value as a cultural rather than sociological phenomenon. But the issue in Juice is that performance in the service of self OR others is MORALLY DUPLICITOUS and can not be redeemed from that characteristic by any act of performative beauty or retreat from action.

Of course, no reader ever reads quite as another does and Giles’ brilliance is to capture, in brief, telling thematic motifs which open up a book that revels in its own feeling of evoked long duration of time and space and the exigencies of travel within them. As Giles says the novel is 513 pages long, but its scope in terms of global travel and extension through time is greater, even invoking an ancient foundational literature of sagas that are endlessly remembered, quoted and cited (for the ‘world is older than you can imagine’). Most of the narrator’s autobiography is told in a narrative framework with its listener (once a listener to the narrator’s story of his past has been found – a bowman (meaning nothing more than a man carrying a bow and one arrow and threatening its deadly use) constantly, though he keeps listening, reminding the narrator that he seems to talks forever. ‘Are you still talking?’ he says on page 146, with 371 pages yet to go.

The time of reading a novel is always a significant factor in our perception of it and this novel I have been reading (I finished it yesterday) since roughly October 25th 2024. There are good reasons for that. My husband fell ill and was hospitalised soon after I started it, coming out of hospital over two months later after a scare in which the hospital urged him to sign a ‘do not resuscitate’ [DNR] document. On his return after double pneumonia, his mobility and independence were heavily compromised.

Time for reading then was scarce and had to be caught at hospital visits where Geoff could not communicate or just before sleeping when I had virtually no ‘juice’ left to do anything at all. My available time is greater now as he returns to independence. I therefore finished the novel only yesterday (15th February). Three and a half months is a long time to be reading a novel and that fact alone heightened my response to thus novel’s metaliteary features of reference to how fiction organises reference to different kinds of time and space.

The one that Giles notices is one of the ‘book’s strongest aspects’ in his view: ‘its presentation of radically different annual and diurnal cycles as though they were entirely natural’. But time present in its ‘annual and diurnal’ passage is only one aspect of how time is treated. Time and space are the stuff of social cognition embodied in work routines, but they are also embodied in cultural artefacts appropriate to difference experienced in the physical feel of time on the body and mind. And beyond that, they arevembodied in literature. The sagas not only cause us to imagine the advent of time and space but their function.

Giles says the book has:

a double retrospective narrative, by which the protagonist looks back on both his own life and also earlier periods such as ‘The Dirty World before the Terror’, when unspecified bad events happened. ‘As you know,’ says the narrator to the bowman, ‘that age of turmoil was universal.’ As readers we don’t ‘know’ any such thing, of course, but by this retrospective strategy Winton makes his post-apocalyptic scenario appear entirely plausible.

But novels rarely use interesting and masterful narrative techniques for their effect of creating a plausible narrative only. The technique is, after all, not confined to literary documents but one used in the narration of the past, present, and future for ideological purposes. If this book is oral autobiography, at least in its performative aspect, it has a lot to say about how stories, even when they seem not to be such, get invented for a human purpose. The narrator joins a semi-secret organisation that uses terrorist techniques and is often called the Service. They justify these techniques by taking control of the narrative that explains their actions and the times and space in which they occur, including (as the recruits get relatively more hardened to their military function of the ‘acquittal’ (a nicer name for extermination) of its enemies – though to be remnants of the Dirty State, the most famous having the name EXXON – a narrative that justifies killing the innocent children of their enemies. They emphasise their service ideal in their recruit selection, initial induction and the training it and its learners call ‘Basic’, even though we know this only through following the unreliable half-knowledge of the narrator as he experiences these things. Every ‘subject’ is transformed and integrated that might justify the Service’s killing function. Its instruction personnel in ‘Basic’ get called names like Politics, History, Health, and their conjoint stories tells recruits that not only was ‘the Dirty World rotten to the core’ and ‘gorged on the future’, and, as all recruits could parrot ‘the future they ate was ours’ since they robbed a new world of its own past locked in memories that were not allowed to see the light of day.

The function then of the Service and its recruits is to acquit the lives of remnants represent an old false ‘Dirty World’ and with it construct a new sense of the passages that matter of time and history with reconnected pasts, reinterpreted presents and new future. The Narrator, puzzled by fighting an enemy representing the past not the present says to the Instructor called Politics that ‘The Dirty World’s long gone. These people are dust now’. But, Politics tells him that though ‘the empire died’, ‘its bloodlines and networks did not. Its culture endures’. Its ‘scions and factors and collaborators persist in the shadows, and, as we will learn later in the cradles of their families, thus demanding baby and child acquittals too to rip ‘out their roots forever’. (2) And what gets acquitted with the flesh of the Dirty Worlders’s remnants is the fictitious history of the world they represent and which had served their interests. In effect the military performance of the narrator, so often and so disturbingly related to the bowman (who, also being a Service recruit, must know it too) is secondary to their revision of how time works. They did not know the supposed ‘crimes’ of their victims as they enter into their slaughter, except by virtue of the stories and the characters types in them related in ‘Basic’. They identified themselves with the agents that tell of time and are not merely mechanical or clockwork (3):

This passage was one that especially spoke to me in the context of my trek through the pages of this novel during external events that were themselves difficult (and sometimes painful) for the memories of each episode of reading had to be drawn into a ‘long view’ of the novel as a reading event within my life. As it was, I was desperately trying to hold together my and my husband’s relationship well as the novel’s fragmented background histories and the relationship narratives they fed into in the novel. Is it clearer if I say that reading the novel had to be an experience of keeping the people, events and language in it in a position that they ‘kept memory alive’.And in doing so, it invokes the manner in which literature sets itself up as the filter of ideas of time, history and the passage of action, ideas and feelings through them. Speaking to his wise mother, she tells him a version of history that valorises the life of the ‘plains people=: growers and conservers even in the worst circumstances in the form of peoples she knows as The Countrymen. History must have involved some ‘waiting in the cave’, for them when the world went into the Terror of civil war. His mother insists those ancestors must have been ‘good at waiting things out’. And she proposes a world with not only more time in that than the sagas the narrator refers to, for the:

… world is older than you an imagine. And people have lived and done things and made things – and dreamt things -on a scale you can’t imagine. The Countrymen will have their own sagas, stories older than any we know.

How?

Because they had world enough and time. [4]

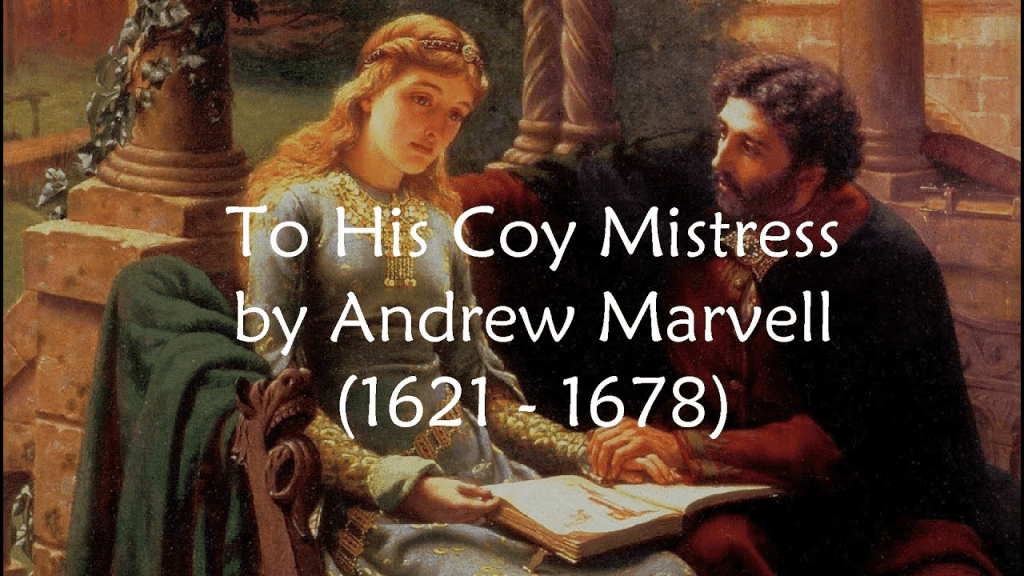

If the mother’s story references the Aboriginal mythical world of the ‘Dream-time’, it also references Andrew Marvell’s To His Coy Mistress, a poem about impatience in waiting for permission to make love to his beloved.

Had we but world enough and time,

This coyness, lady, were no crime.

We would sit down, and think which way

To walk, and pass our long love’s day.

...

My vegetable love should grow

Vaster than empires and more slow;

The impatience of getting want you want, even from a book or a poem is expressed best in the most famous lines of verse about the passage of time’s through space or ‘world’.

But at my back I always hear

Time’s wingèd chariot hurrying near;

And yonder all before us lie

Deserts of vast eternity.

Hence, though only the first line is quoted by the narrator’s mother to give notice that our view of time (past, present and future) needs constant revision, the last lines of the poem speak in the narrative and characters of the novel:

Thus, though we cannot make our sun

Stand still, yet we will make him run.

Though the sun here is male – in line with the Apollo of myth – the sun is the emblem of how we experience the passage of diurnal time and I have no doubt that this is the origin of the name of the narrator’s lover, found in the hamlet nearby him but originally from Perth in Western Australia, and his eventual wife. Yet in making his Sun ‘run’, the narrator finds she runs away together with their daughter, never to be reclaimed as Paradises rarely are – at least in the same form. The sun is the focus of ambivalent experience in this novel, as Giles very cleverly notices:

In this era of climate catastrophe, when ‘the sun ate everything in sight’, it had become necessary to spend the months from October to April living underground; even in winter, it was impossible to go outside after mid-morning. ‘Winters were hot,’ recalls the narrator, but ‘summers lethal’. The remark on the second page about how the sun ‘[b]reaks free of all comparisons’ directly echoes the point Jacques Derrida made in ‘White Mythology’ about how the sun is ‘the nonmetaphorical prime mover of metaphor’.

On Derrida however, I have nothing to add, and neither has Giles in this particular passage. Yet the character Sun is constantly waiting for the narrator’s tardiness, even in the proposal of marriage which has to be prompted by his mother, and the pursuit of the sun is at all times, and eventually and decisively causes a break in their relationship, marriage and family, seen as antithetical to the idea of devoting himself to the Service. Indeed perhaps Sun is less a person than an allegory, like the ‘woman clothed in the sun’ in Revelations Chapter 12 verses 1 – 2, of an attitude to experience that dramatises the duplicity in the narrator’s attitudes to service on the one hand and the pursuit of personal truth on the other:

Sun brought such joy and revelation – it was intoxicating. And perilous. because for me this was already a precarious season. i was adjusting to my new and much more complex life. One I could never share.

…

Unquestionably sun was a miracle. she understood me. Still I saw this season with her could only be temporary. I told myself to enjoy it while it lasted. … Because, in truth, I was clinging to Sun in a way that put my service in jeopardy.[5]

Sun is also always a kind of index of time. After their first meeting with her, his relationship is mediated by waiting whilst being ‘skittish and fractious the whole time’ until he rather overfills his time with her. I can’t not notice that her name and the light she is named after often as the day progresses, starting with a scenario when a beginning (of light) projects ‘out ahead’ on a future path, whilst later as the sun rises in the sky, somewhat nearer midday it is hinted, Sun stands (put there by the narrator with the past behind them like ‘the gulf behind us’, where the word ‘behind’ does ambivalent work) on the edge of a descent, which leads on to a conversation about the long duration of the world’s historical genesis:

This is amazing, said Sun in the first light hit the rocks underfoot and sent our shadows rippling out ahead.

…

As the sun rose over the gulf behind us, I led Sun out to the lip of the biggest canyon on the cape. It was quite a hike … I needed the time to settle, to gather my wits and reset. This girl was dazzling.

Sun begins to shed revelatory light (to dazzle with it perhaps) even on the heroic sagas that clearly have taken something from the Gospels in the way of talk about dark and light. When the narrator says that ‘there is only so much of the world we can see. … And know.’ she says almost like a sibyl (but citing I Corinthians chapter 1 verse 12): ‘Yes. We saw as through a glass darkly‘ followed by: And the days were rendered dim by the deeds of the dead and the living’. Even if the novel had worn an allegoric intent in as fully as does Edmund Spenser, we could not have had such a confluence of the idea of the Sun, with different kinds of light that speak through instances of time and space.

And all this takes part in an examination of history as it is told, believed to happen in the past and present and how it might be led (as Sun is led above by the narrator) to the future and how time is scheduled into rotas, routines and practices guided by the environmentally temporal, whether diurnal or seasonal/annual. Routines keep you safe perhaps but they also take juice to perform and sometimes that juice is severely depleted. In those occasions the novel, and the narrator, flee to caves and boltholes to regroup or hide, and the bowman’s bolthole seems ambiguous in this way. [6] The narrator’s mother tells him that when when pressurised by history, her ancestors metaphorically ‘laid low’ under the ‘shade of a tree’ from the sun, eventually seeking more permanent and secure ‘refuge’ or hiding place in a cave. [7] The land offers refuge unlike the sea, she says later, thinking of her eco-warrior dead husband [8]. The narrator is attracted to things like a ‘rock shelter’ the land was once the sea and it gives him a sense of womb-like oceanic security, as remarkable as any motif from Jung.[9] later the narrator and Sun both rappel down a cave wall to find the remnants of sea water in a cave. [10] but staying in a hole is not only refuge, it is a retreat as the narrator tells the bowman. The narrator in fact says that the bowman will never know if his male guest has ‘got juice’ or is afraid. the reason for that is that wondering in uncertainty is all you can do: ‘Down here on your own. In your hole’. [11]

But if retreat from action is fruitless so too can the relentless task of performance in front of others, in any capacity, not only fatigue you but cause you to lose yourself in either the service or trust of others – a lesson underlined by the sims (simulacra people or robots who take much space later in the novel) for performance is duplicity – being other than your desire (for Sun for instance):

I’d given a good performance for the Service. I’d convinced them of my worth once again. And yet I was tired of duplicity. I felt I had no more to prove. … oh be just myself. Not a rendition of myself. [12]

The whole dilemma raises how we demonstrate to self and others our value and worth and whether there isn’t ambivalence in trying to satisfy self rather than others for the ‘performance’ in the latter case has to be believable by yourself not just others. After time sims, who are ‘instruments for others are not unlike people of flesg who wonder to each other whether being in service isn’t always being ‘used as an instrument’. [13] For the Sims a life of active service, even at the cost of severe betrayal by humans (their usual fate in the novel) is better than being in storage laid useless in a cave, warehouse or bolthole, but the narrator mirrors that learning regarding the fleshed out bowman and himself later: ‘Beats storage, I tell him. It beats hiding. don’t you think?’ [14] The short chapter ends with that question but there is no obvious answer.

Giles’s reading certainly accommodates my last point and I wonder again how much I add to him. For instance he says of the use of something like heroic ancient classical epic as a model that it is ‘reminiscent of Winton’s previous novel The Shepherd’s Hut (2018), which again sought to reposition the classical tradition of Western pastoral in the context of Australian realism’. I wrote on that novel very briefly myself in a blog (see link) without mentioning the pastoral. Spenser and Milton both wrote pastorals before they wrote their epic stories, in order to model themselves on Virgil, who did the same, but is Winton doing the same. Perhaps but not as the definition of his purpose. So much is about a native Australian dream-time art that perhaps outstrips the Western colonial tradition about fighting and fatigue consecutively. Meeting the bowman the narrator says ‘I’m tired of fighting’, only for the bowman to aggressively retort ‘Maybe you’re just tired, full stop.’ [15] Yet tired or not the most significan memory of the novel – it is repeated throughout – is one the reader is unlikely to have heard and less likely to remember – the story of finding a chert he carries with him through the novel and which resonates with what he has to say about time and history and is almost certainly native Australian:

A chert the size of an olive pit Pink. with a chisel-edge as old as human consciousness. …… A fetish. Sun once told me a stone is an expression of the earth, a signal of time. But it’s also a relic of experience. A thing propelled into the world. Dragging its past like an afterglow. And it’s just a rock, but its journey isn’t over, and neither is its destiny fixed [16].

Small fashioned things are rarely remembered, but they embody time better than some other stories, with a past crystallised in it, a present that varies with progression and always an unfixed future. The point is how do you make your destiny – do you ‘perform’ a role which may be dubious and duplicitous, or do you hide. In fact we do both. Some kinds of hiding – of our own willed ignorance about species extinction, global warming and global deterioriation – are problematic. They may bring about the contradictions of this novel’s setting and stories, even in being an eco-warrior, but it is unforgivable to think that you can only perform if you have certainty about securing a just destiny. There is something necessarily true abot learning ‘to take the long view’ and ‘keep memory alive’ and ensuring ‘it still meant something’. We may get it wrong but if the destiny of a small chert is not fixed neither is yours or mine, or the globe’s. We have to fight through the fatigue, resting when we can and must, but though we do this – nothing will be guaranteed. Time is not like that and is not our toy.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx

_____________________________________________

[1] Paul Giles (2024) ‘‘Schooled in doubleness’: Tim Winton’s enthralling new novel’ in The Australian Book Review (November 2024, no. 470) Available online at: https://www.australianbookreview.com.au/abr-online/current-issue/1008-november-2024-no-470/13263-paul-giles-reviews-juice-by-tim-winton. If it helps the references to the oil companies using the manufacture of ‘juice’ to render it into power and entitlement for themselves are on page 111, and the reference (not the only one) to juice as personal energy Giles uses is on page 282: ‘It takes a lot of juice to perform’. However I aim to use the latter quotation, a little extended above for the idea of performance needs elaborating beyond Giles’ explicit use of it here.

[2] Tim Winton (2024: 119 – 121) Juice London, Picador.

[3] ibid: 131

[4] ibid: 66f.

[5] ibid: 172

[6] ibid: 16

[7] ibid: 31 – 34

[] ibid: 55

[9] ibid: 64

[10] ibid: 184

[11] ibid: 354

[12] ibid: 305

[13] ibid: 499

[14] The sims make the statement ibid: 421, the narrator mirrors it ibid: 461.

[15] ibid: 15

[15] ibid: 512