In Danez’s Smith’s latest collection, Bluff, one way of reading the course of history lies in the poem made from footnotes within a longer poem, rondo:‘freedom was a door into a bigger cage & when they couldn’t shackle the necks anymore, their metal met the mind, they chained time, chained the money, chained the dreams & noosed futures‘.[1] I could not be more overjoyed that at last a poet rejects the teleological vision of history as destined for some dubious purpose serving the already entitled and just celebrates the apocalypse itself, in as hopeful a way as possible, which may not be very hopeful. Nevertheless, ‘maybe God’s love is everything ends. / maybe time is our sentence’.[2] Moreover: ‘It’s the end of the world, and who gets to escape into the fantasy of nature’s endlessness’. And, as for our destination; ‘there ‘is a place’ but that’s ‘my own / somewhere far from your knowing’.[3] This is a blog concerning Danez Smith (2024) Bluff London, Chatto & Windus.

Some of the questions raised by Danez Smith’s poetry I am leaving out: they fill me with too much sadness and a sense of the hopelessness that the entitled white races often feel at the exposure of their collusion in history without any clear means of escape therefrom. There is in these poems still a remnant of the angry rejection of the white appropriation of Black voices and Black beauty, but it has much more sadness within it I think than in ‘Don’t Call Us Dead: Poems’ (2018) & ‘Homie: poems’ (2020), about which I have already written a tortured old white bloke’s blog (see it at this link – but that’s not necessary). In this volume, Smith can still say:

I want to write about my life with my words the problem is who listening, who editing[4]

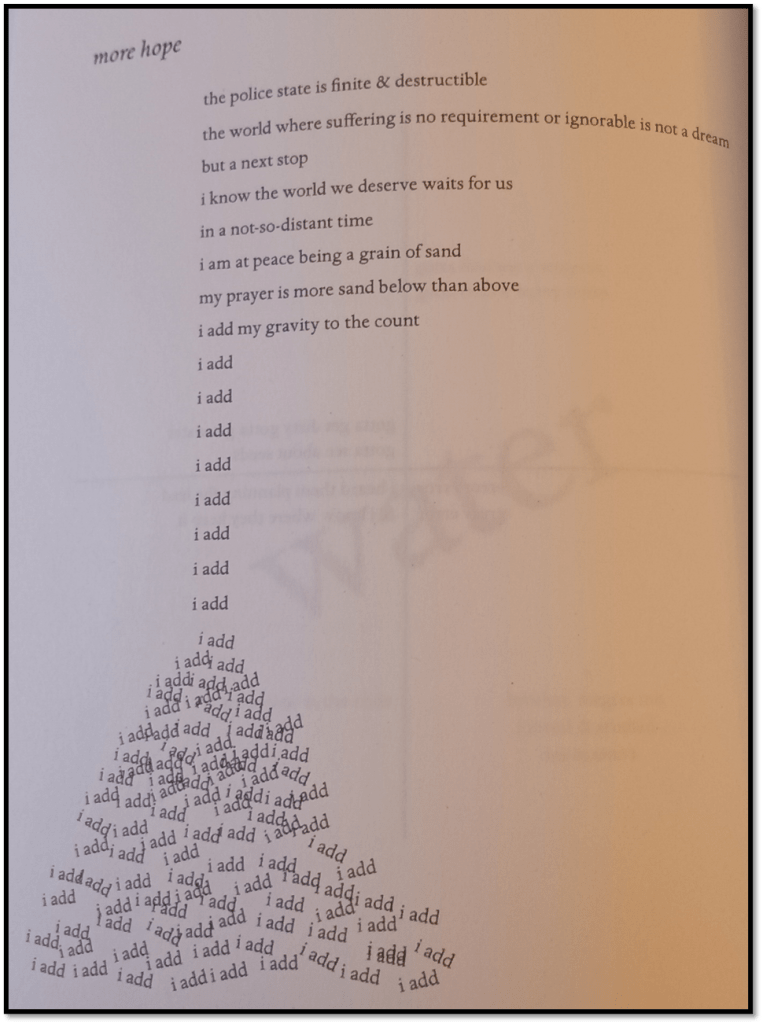

I have no doubt that, as I read those lines and others and respond to their musical, intellectual and reflexive content, I am overhearing words not meant for me, and possibly (even perhaps without me being conscious of the fact) editing them as I listen in order to fit into truths I hold self-evident that are in fact just white folks’ propositions about the world and not approaching an understanding of this poet. Of course I hope that is not true and maybe, as the sand drips through the hour-glass in the company of what Smith adds to our world, it might, eventually, not be. In this last sentence I refer to the poem more hope. I can only show that by sharing an image of the page:

Danez Smith, op.cit: 118.

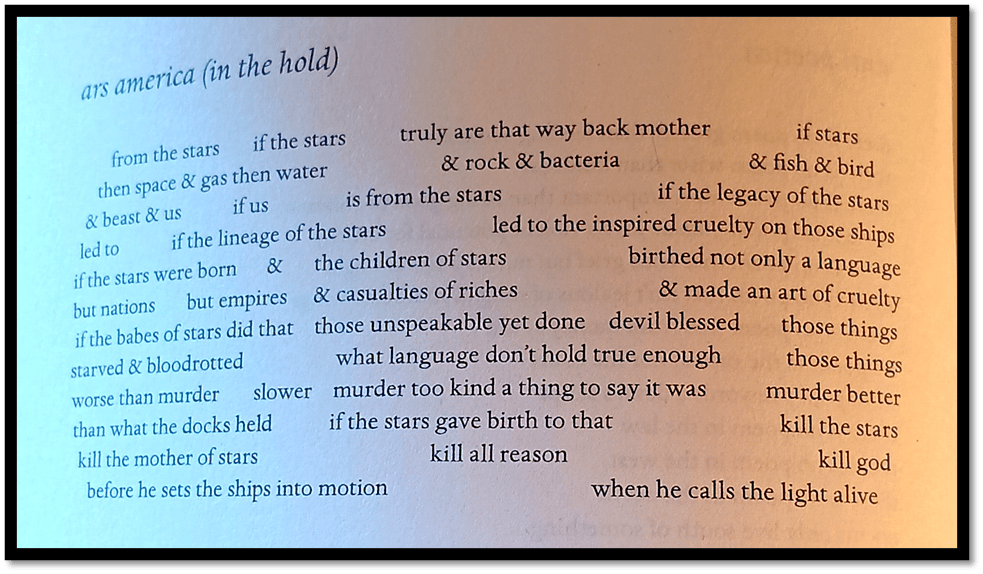

In Bluff, as well as making a world by naming it with white names, ideas and responses into which Black people cannot get a hold, other than in the memory of a cargo ship’s ‘hold’. As for the ‘hold’ where Black experience is contained and held back from view, it becomes the form of the poem ‘ars America (in the hold)’ – below:[5]

It is a ‘hold’ distorted to create shape into which to fit Black experience for our only tool – language is white-acculturated unless we redeem it through our address to primarily Black audiences and in the syntax of developed Black oral culture: ‘what language don’t hold true enough’. And indeed, white culture cannot help but to go on crowding Black experience out, as in these lines from My Beautiful End of The World:

I’m often alone, but not alone-alone, but I’m myself in the midst of white folks. I am the only of my people along the trails; sometimes a dark stranger will pass me and we get that moment of recognition in the company of trees; occasionally a friend is by my side and we are alone together along the crowded and worn paths. It’s the end of the world, and who gets to escape into the fantasy of nature’s endlessness.[6]

The poem ’I’m not bold, I’m fucking traumatized’ contains the remnants of the argument from Homie but now presented as trauma not just bold anger, Nevertheless the lines about having ‘like four white friends, maybe / a dozen if I’m being generous & that feels brave’ show the ‘little deaths’ such friendship expose Black experience to:

…. every one of their white hands handling me what I had already read and knew …..

The more definite pin-down of the fault of laboured friendship and belated wokeness captured in:

… & it was

like the they were just now opening their eyes

& all us once shadows had shapes, proper names.

//

does it bother you when somebody talks

about your people, as a concept, right

in front of your face? What does your skin feel

like when it’s evaporating into theory? … [7]

Of course ‘liberal white guilt’ is itself a problem in all this and I can’t escape it – the issue is I suppose that white people must solve their own difficulties with what they call the other, before they inevitably continue to ‘Other’ Black people. And I look back to see myself talking about Smith’s ‘people as a concept’ and presenting it to him in his face (though poor blogs from the UK are unlikely to reach him). I wonder if I did that in my piece on Sioux Falls (see it at this link). I loved that poem, found it beautiful but is that just appropriation of the function of the poem from the voice of traumatised experience. For instance take the moment below from my own writing.

The comparison in it of Sioux Falls with Arnold felt real to me, but I suppose it would Arnold being the repository of a certain entitled view of white culture that as a working class white boy was not even mine until I colluded with the view it was through white educational traditions. Moreover, inevitably the comparison is held together by ‘theory’ (maybe the theory of ‘Black perspectives’ but still a theory, and mainly owned by White writers who are still the majority in the academies and the supposed authorities on it. As I think this I feel; shame but that is less important than owning the problem, as I claim Danez Smith does in relation to indigenous American populations in that poem, and in others, the genocide of yet a more modern settler colonialism in Palestine:[8]

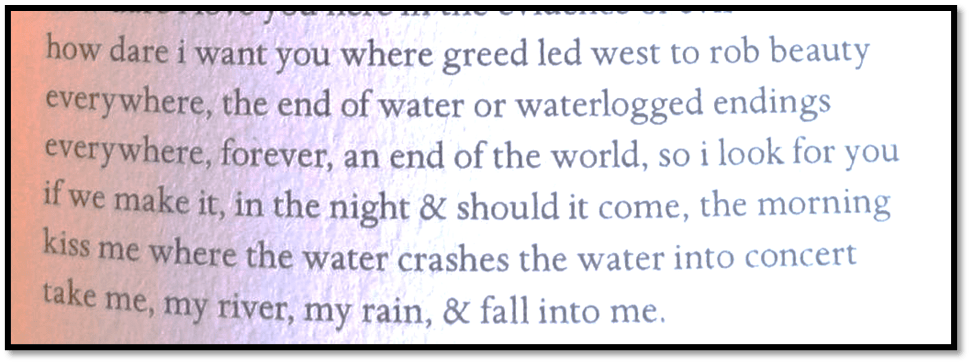

That Smith can only ‘dare’ this rather than assert his right as Arnold does, despite the obstacles of what elsewhere he called ‘Philistinism’, to what is the ‘ land of dreams, / So various, so beautiful, so new’ that poetry conjures knows all dreams are tainted appropriations of the dreams of others. Dover Beach as a place in space is an entirely validated boundary of English topography and culture, a limit of what it means to speak and talk in English as Arnold sees it, having few Transatlantic yearnings as Dickens and Oscar Wilde had. Sioux Falls attests to a genocide completed, not only of a people by its varied cultures; though its survivors, like Tommy Orange (see my blog at this link) look to find a new form of creativity in compensation and a respectful appropriation and sharing of Black, queer and Native American marginalised histories and topographies. One can only ;’dare’ to hope that such appropriations are not as insulting as those of the White West of other subordinated cultures, for the aim is NOT in Smith to subordinate. If his wonderful poem ends with a ‘concert’, a performative togetherness, it resounds throughout with clapping where performer and audience, self and its others become one in mutual admiring praise (being clapped as in a theatre) and intermingling of ‘flow’ between waters and the fluid bodies water represents.[9]

.It is time though to move on for change can only happen if you do taking, as you must, the contradictions of one’s own history, that beyond the accident of your personal birth, and trying to gain what Danez Smith offers, even if not directly to me, but accepting interpellation as in these beautiful, moving but painful lines – painful to say no doubt, but also to hear (the extract begins with institutional white response (Forward Prizes and so on) of Don’t Call Us Dead:

They clapped at my eulogies. They said encore, encore. We wanted to stop being killed & they thanked me for beauty & pitifully, i loved them. i thanked them . i took the awards & cashed the checks.[10]

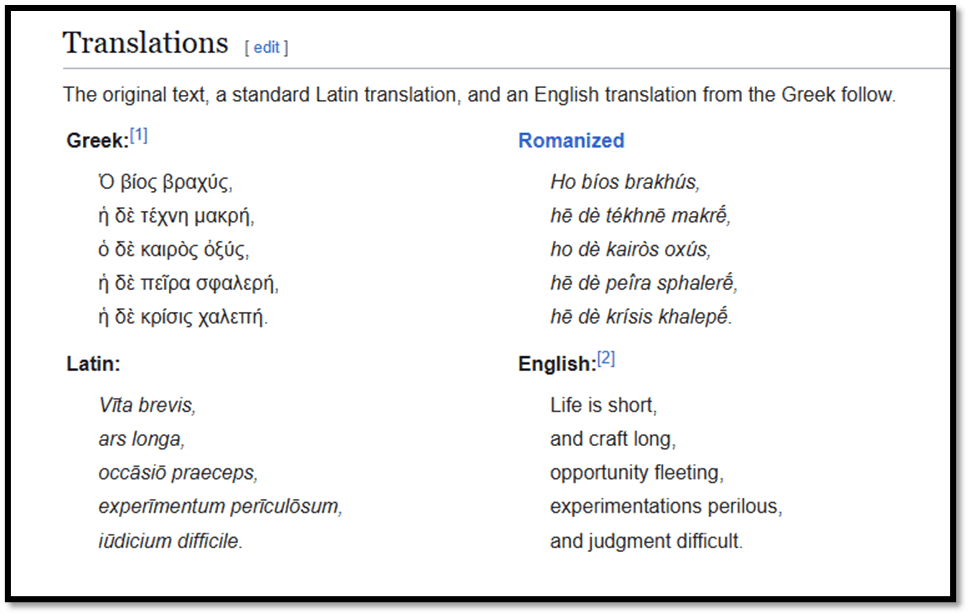

Danez Smith too hates his contradictions and makes more poetry of them lest they actually add up to ‘less hope’ for change than new hope. That new hope is captured in this volume in the progression through of poems named both ‘anti poetica’ and ‘ars america’. I do not know if there is a homophone on ‘ars# / arse’ in Smith’s rendition but there ought to be. Meanwhile the poems recall the tradition as enshrined by the famous aphorism ascribed in its original Greek, with the order of life and art reversed to Hippocrates.:

I think I know Smith intended reference to this through themes in the poem rather than by the acknowledgements he gratefully makes to modern poet-colleagues he refers to. The ship’s hold and the naming of a ship as a ‘craft’ plays on the change from the Greek term tékhné (τέχνη), which literally referred to skill or craft to the sublimation of the word in its Latin use and translation as ‘ars’, referring to a more modern term of art refined from mere craft and skill into something nearer the idea of high art, an art that was not made for popularity as the Greek poets made it but for the refined and idle classes of aristocratic Rome. The final poem of this volume is entitled ‘craft’ which is a poem about the poet’s ‘craft’ and its meaning which though it often creates monuments to a dark time looks forward to a post-apocalyptic future. Elsewhere ‘craft’ is mentioned to indicate the poet’s craft indeed but also a ship and a boat, and thus symbolically rhymes with the many ships remembered in these poems in which Black people came to America held in chains in their ‘hold’. In one of the earliest obvious apocalyptic poems the lyricist says:

i want to believe i would take debris & craft an ark

An ark is a redemptive craft and the word ‘craft’ in these lines could be either a noun denoting an ‘ark’ perhaps or a verb (derived from the Greek noun τέχνη). As an ark, it is an expression of the hope that the poet might take the fragments of a dirty spoiled present and the history it drags along with it and make something that sails above the world-destroying flood. However, what the poet actually produces or crafts is a poem of violent vengeance against the outcomes of a long history of white supremacy, and wondering whether he might not ‘hunger’ to ‘hunt’ the white man as Black men were hunted and ‘dig a tunnel’, presumably an escape tunnel:

through the lung just wide enough for the spirit to flee[11]

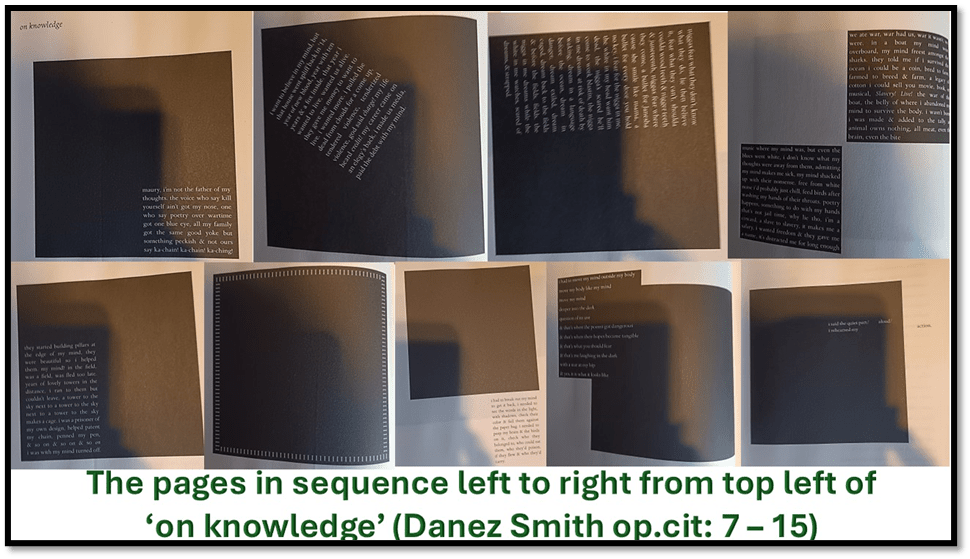

The problem that this volume addresses is whether in a time where Black brothers, sisters and trans persons are killed, poems don’t rather compound the evil and validate it. The first substantial poem ‘on knowledge’ illustrates the point perfectly but not obviously.

It present various options in which Blackness is either the page on which I write, and in which case I must write and type in white. Moreover since pages are by convention white (or off-white, even that black page is a ‘black box’ which imprisons me inside it, even where I try to shift its borders or boundaries. Or instead I type in black but can only do that on either a whole white page or in the margins of a page with a black box. Whichever way I turn my craft (represented in the revolutions and movement of text I am trapped, as in a black box into whose interior margins my ‘I’ is forced, and forced to look white. The poem after that one has marginal black text outside the box in order to, forced into justified borders (so each line is exactly the same length as the last) which I can’t reproduce below:

see the words in the light, with shadows, check their color & fail them against the paper bag. ……[12]

The issue for Danez Smith is that whatever he says or writes is appropriated into the oppressor’s language as the only language he can write, for it is ‘mine’ even if in another way it isn’t except for the street versions of it.

No wonder then that this is torn between an elegy for things that end and a love poem to a final and ultimate end of this oppression in some unsociable apocalyptic time and some possible apocalyptic place (sometime & nowhere – nowhere being an acceptable translation of the non-word, coined by Sir Thomas More, ‘utopia’). William Morris writes his socialist Utopian novel as ‘News from Nowhere’. In a volume full, especially at its mid-point of poems named after places (‘Sioux Falls’ being a good example but ‘Denver’ being more obvious) Danez Smith looks for bits of the paradisal and utopian (or Edenic) inside a fixed time and place but usually in the poem has to show that if ‘hope’ survives, it survives in the long haul – in ‘ars longa’. The triumphant poem of Eden and paradise is the wonderful long poem ‘soon’, which never names its place or time except as ‘somewhere’, the obverse only of ‘nowhere’ or ‘soon’, ‘sometime’, and it is doesn’t matter if neither place nor time exists for it is a togetherness of human love:

We see the door My eden doesn’t exist eden is an action a we …..[13]

‘We’ is also beyond ‘I’ and even more so beyond an ‘i’, it is a coming together of bodies in liking/desire likeness in diversity is a metamorphosis of diversity into likeness: of course such utopias don’t exist. But that is the only condition of poetry and that is the meaning of the final ‘ars poetica’ poem, which begins ‘’fuck all that other shit’. Just as he admits poetry can be false (and poets have known that as long as there has been poetry), the poem rises into a crescendo where time and space are confounded in nowness and ‘stillness’:

.., in these lines, in these rooms i add my blues & my gospel to the record of now, I offer my scratched golds to the blueprint of the possible, dear reader wherever you are reading this is the future to me, which means tomorrow is still coming, which means today still lives, which means there is still time for beautiful, urgent change which means there is still time to make more alive which means there is still poetry.[14]

I will hate myself for saying it but this poem uses the word ‘still’ as Wordsworth and Keats use it, to indicate both continuing action that is still is happening and will still happen in the future as it still happened in the past (hence it makes more of the dead ‘alive’) and something both totally motionless and totally silent. And yet that still thing still runs like ‘water’ (a vital symbol in the volume). Of course these ambiguities in one qword are all about time and space.

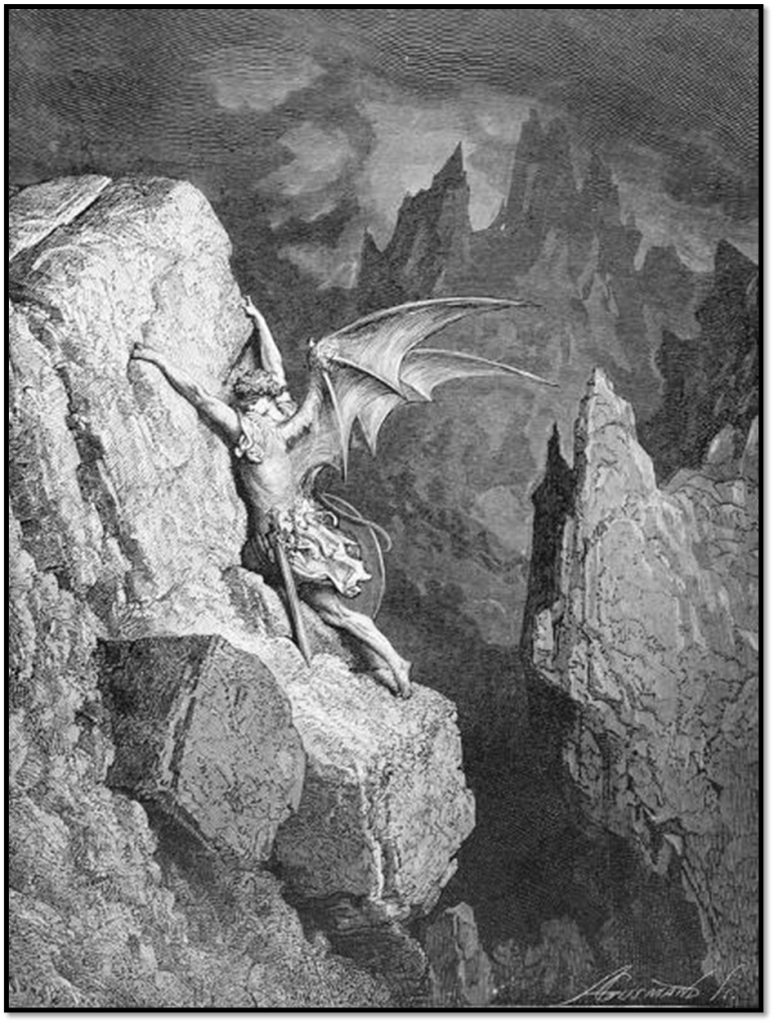

The proto-religious meanings of the end in fact started early in the poems, for within its duration, the volume must make a possible heaven out of a definitive Hell of killings and appropriation. And If I evoked Romantic poets above let’s also evoke William Blake, for these poems recreate th notion of great poets, even Milton according to Blake, being of the ‘devil’s party’ without knowing it and finding in Satan the energy that will bring change. Smith’s Satan appears in the first poem about hope and hopelessness, that will progress to ‘more hope’. The poem is called ‘less hope’. In it the lyricist renounces God’s party in a kind of public statement and unites himself to the ‘Devil’s party’ publicly. Having said that he was forced to follow God,

I abandon you as you did me, c’est la vie. but sweet Satan – OG-dark kicked out the sky first fallen & niggered thing -what’s good? … Satan, like you did for God, I sang. i sang for my enemy, who was my God. i gave it my best. i bowed & worse, smiled. Teach me never to bend again.[15]

The aim here is to take on the stereotypes used in but also against Black culture. The OG-dark for instance reproducing folk stories of the ‘original gangsta’ stories, and tying their resistance to the rule of white law to the situation of Milton’s Satan;

Infernal world, and thou profoundest Hell [251] Receive thy new Possessor: One who brings A mind not to be chang'd by Place or Time. The mind is its own place, and in it self Can make a Heav'n of Hell, a Hell of Heav'n. [ 255 ] What matter where, if I be still the same, And what I should be, all but less then he Whom Thunder hath made greater? Here at least We shall be free; th' Almighty hath not built Here for his envy, will not drive us hence: [ 260 ] Here we may reign secure, and in my choyce To reign is worth ambition though in Hell: Better to reign in Hell, then serve in Heav'n. [263] Book 1: Paradise Lost. See https://milton.host.dartmouth.edu/reading_room/pl/book_1/text.shtml

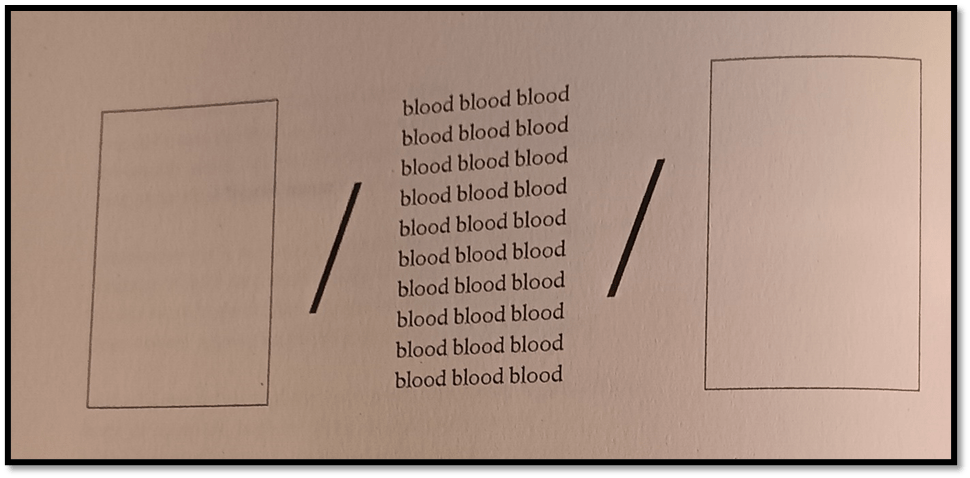

An art of song owed to Satan is there because God ‘niggered’ Satan, made him a thing defined by negative stereotypes to avoid any further direct challenge to his self-authorised law, as white law and white culture did to Black culture. And like Satan Danez Smith awaits the last battle where all binaries will turn in on themselves and what was lathed as ugly and ‘dark’ becomes the true bearer of light (Lucifer) in overturning a status quo in which we must see as ‘good’ only what the owners of law and land tell us what is good – Lucifer indeed. And sometimes Lucifer has the feel of Franz Fanon – predicting that the door to Eden will not be by meek peace but by the path between two sealed white boxes of a flow of blood.

Danez Smith op.cit: 134

Of none of this though am I certain – for love, blood and water are all fluids and might flow into each other like the Sioux river at Sioux falls.

That is unsatisfactory place to end but all endings are such, like those in Sioux Falls, where endings are ‘everywhere’ and forever – in an opening up of space and time (no place – utopia) and are like waters falling, not angels falling, into other each other (as river or rain) and the ‘sentence’ of time has been passed and ‘maybe God’s love is everything ends. …’ and that no-one ‘gets to escape into the fantasy of nature’s endlessness’.[16]

From ‘Sioux Falls’

You can’t ever get Danez Smith. Approaching the themes evokes the hidden allusions to whole traditions, such as the querying of Whitman’s phrase from The Song of Myself, ‘I contain multitudes’ that then leaps back into the theme of what it means to ‘contain’ or put ‘borders’ round a thing and then gets self-conscious, as theme and craft in poetry in what exactly a ‘line’ is in poetry and how you draw one in every sense, including where it ends and how it is spaced relative to other lines (it is difficult to quote correctly for that reason in part). Nothing in these poems is ever willing to stop flowing with meaning and formal self-consciousness. Hence what I write here is provisional and for me perhaps only. It helps me get my head around why I love these poems but in no way represents what I think is how they should, or even might, be read. In the end poetry is for me that moment of stillness when motion and meaning still continue to disturb us.

I will report back on hearing Danez Smith speak.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Danez Smith (2024: 38, footnote3) ‘rondo’ in Danez Smith (2024) Bluff London, Chatto & Windus, 35 – 41.

[2] Danez Smith (p.90) From “My Beautiful End of the World” in Danez Smith, op.cit: 88 -92.

[3] Respectively Danez Smith (pages 29 & 27) From ‘headed” & “you don’t even know me / I’m hanging from a tree” in Danez Smith, op.cit: 29 & 27.

[4] Danez Smith (p.82) from “stoop poem” in Danez Smith, op.cit: p.82

[5] Ibid: 4

[6] Danez Smith (p.90) From “My Beautiful End of the World” in Danez Smith, op.cit: 88 -92

[7] Danez Smith (p.70) From “I’m not bold, I’m fucking traumatized” in Danez Smith, op.cit: 69 -71

[8] Danez “poem” in Danez Smith, op.cit: 64 – 66.

[9] ‘how dare I love you here in the evidence of evil’: some thoughts about ‘Sioux Falls’ in Danez Smith (2024) ‘Bluff’. – Steve_Bamlett_blog (livesteven.com). Available at: https://livesteven.com/2024/10/07/how-dare-i-love-you-here-in-the-evidence-of-evil-some-thoughts-about-sioux-falls-in-danez-smith-2024-bluff/?_gl=1*4r980q*_gcl_au*OTg1MjkwNDQxLjE3MjYwNDY4NDI

[10] Danez Smith (p.17) From “less hope” in Danez Smith, op.cit: 16 – 17.

[11] Danez Smith (p.93) From “but how long into the apocalypse could you go before having to kill some white dude?” in Danez Smith, op.cit: 93

[12] Danez Smith (p.13) From “on knowledge” in Danez Smith, op.cit: 7 – 15

[13] Danez Smith (p.136) From “soon” in Danez Smith, op.cit: 120 – 136. A wonderful poem.

[14] Danez Smith (p.119) From “ars poetica” in Danez Smith, op.cit: 119. Another wonderful poem.

[15] Danez Smith (pp.16, 17 respectively) From “less hope” in Danez Smith, op.cit: 16f..

[16] Respectively Danez Smith (pages 29 & 27) From ‘headed” & “you don’t even know me / I’m hanging from a tree” in Danez Smith, op.cit: 29 & 27.

4 thoughts on “And, as for our destination; ‘there ‘is a place’ but that’s ‘my own / somewhere far from your knowing’. This is a blog concerning Danez Smith (2024) ‘Bluff’.”