Cornelia Homburg cites a letter of 1888 in which Van Gogh saw a coal-barge on the quays of the Rhone river that was ‘a grand subject’ and was ‘pure Hokusai’, but it was a subject that he needed to think about painting very differently because, he says: “I’m beginning to see more and more to look for simple technique that isn’t perhaps Impressionist’. The current Exhibition at The National Gallery promises to make you see Van Gogh differently too. What evidence is there of that? I see the exhibition on Thursday 25th October at 2.45 p.m. I refer to the catalogue: Cornelia Homburg (ed.) (2024) Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers, London, National Gallery Global Limited.

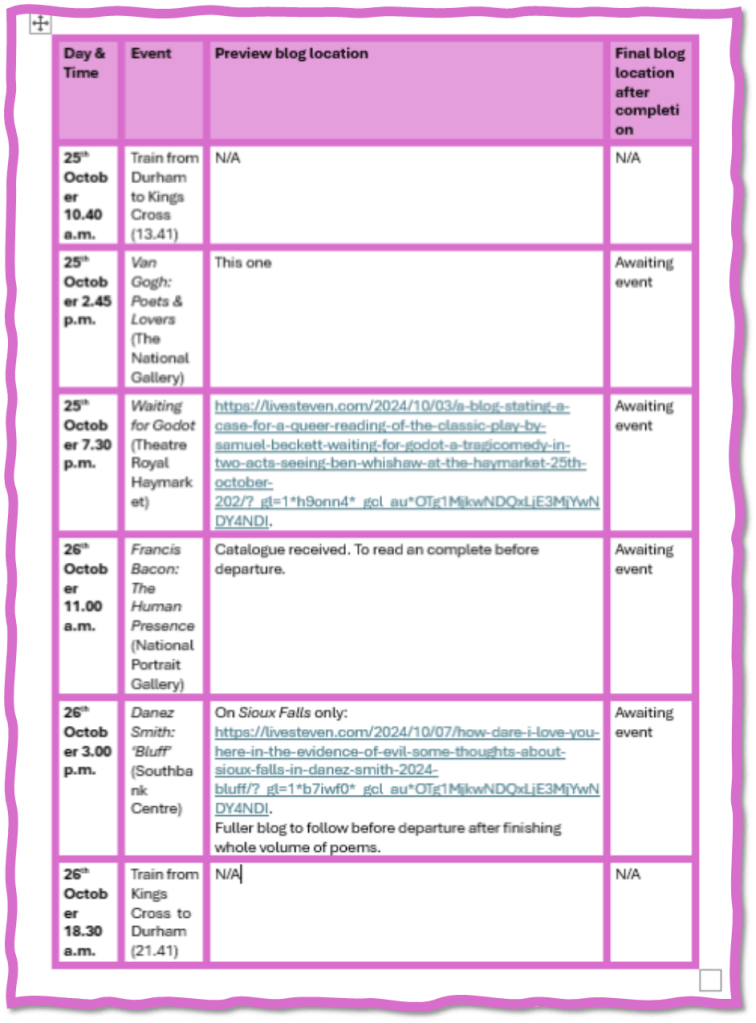

This is one of a series of blogs covering my preview expectations of my birthday trip to London on the 25th – 26th October after my birthday on the 24th October when I will be 70 years of age. My husband doesn’t travel well on trains so he thought I should have my birthday present for myself. He is taking and picking me up to & from Durham Station. I am staying overnight in the Travelodge in The Elephant & Castle (cos its cheap)!

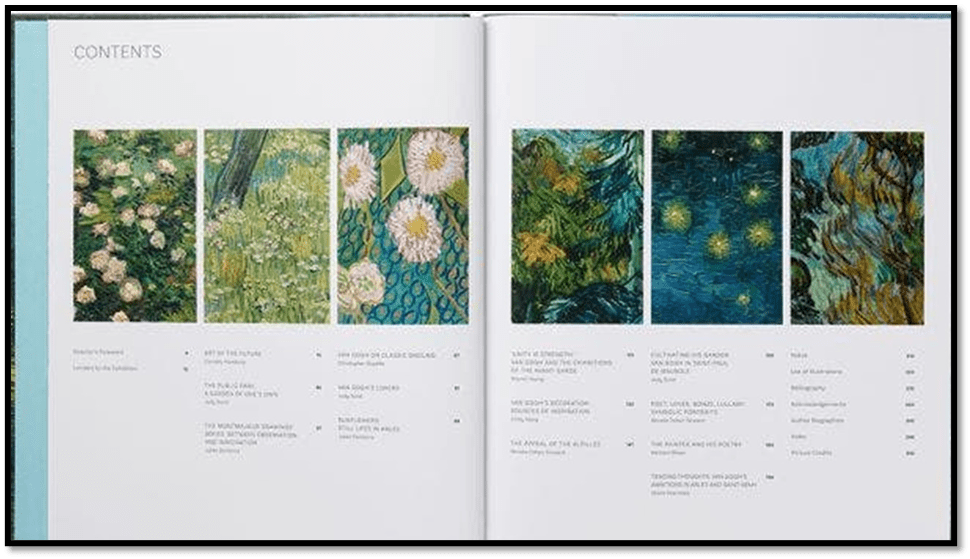

I received my catalogue from the National Gallery shortly after order it and my ticket on 20th September. I finished the book yesterday, taking it steadily and piecemeal through the essays because the print size is very unfriendly to older eyes with cataracts. It is amazing how legibility issues like this mar your enjoyment and attention span but so be it. Largely the essays were worth the effort, though some failed to grasp the editor’s view that here was a retrospective exhibition (the first to assemble so many paintings in England from global sources) in which innovative ideas were welcomed.

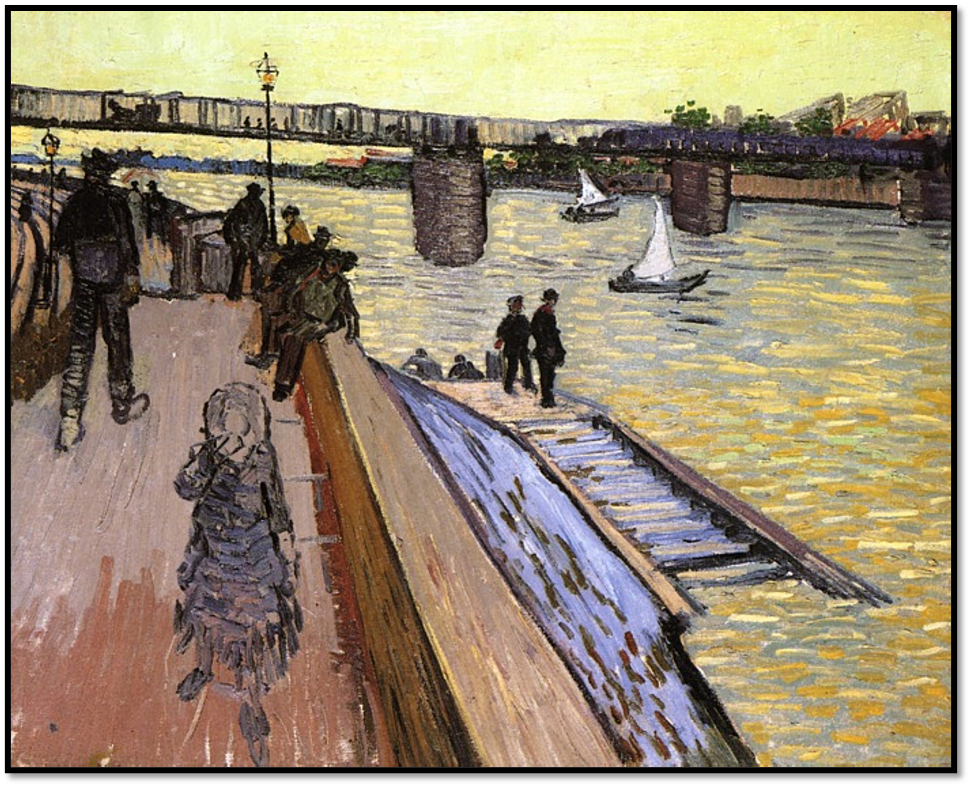

It is the unfamiliarity of many of these pictures to me that so excites me about the exhibition and if the print quality in this book’s printing falls short over many criteria, its reproduction of the exhibits does not. And if anything had to be less well done, I prefer in this case it be the print rather than the reproduction of pictures. For each and every one unknown to me previously haunts me until I get to see it ‘in the flesh’. This effect was immediate for I only turned the pages as far as Figure 3 on page 18 to see a painting that so contradicted my expectations of a Van Gogh that I was astonished. Cornelia Homburg tells us that Van Gogh himself though this picture to be doing things that were extraordinarily innovative – for him and for nineteenth-century Art, something that might allow him to assert some independence of the major Impressionists whose influence over that ‘style’ or mode of seeing was hegemonic – notably Monet and Pissarro.

The aim cited by Homburg is gnomic in its expression by Van Gogh and its aim therefore, in my view, still up for discussion beyond Homburg’s conclusions. Van Gogh says that it is ‘one at least where I’m attempting something more heartbroken and therefore more heartbreaking’. The terms used are barely covered by Homburg’s gloss of them as intending to say his interest was in ‘overall effect, and maximum expression’, or its ‘overall emotional charge’. It bears some links this painting to expressionist method of course – the distorted figures (like the over-elongated man walking away from us) and their non-finito execution, especially the young girl crossing towards us on the bridge , apparently looking up to us but from a face absent of features, the use of foreshortening akin to Japanese prints and it extreme colour contrasts that seem to have a synaesthetic feel, as if blues and yellows set a certain coolness and coldness separate from reds and pinks that are visceral and hot in their association and feel. The painting has a straightforward title: The Tranquetaille Bridge (1888). It is a large painting (4.8 x 80.6 cm) and I can’t wait to see it.[1] The point will be to see how the ‘heartbroken’ is translated into visual and or synaesthetic terms.

The reproduction here subdues the colours in the one seen in the catalogue of The Tranquetaille Bridge (1888). Available at: https://www.wikiart.org/en/vincent-van-gogh/the-bridge-at-trinquetaille-1888

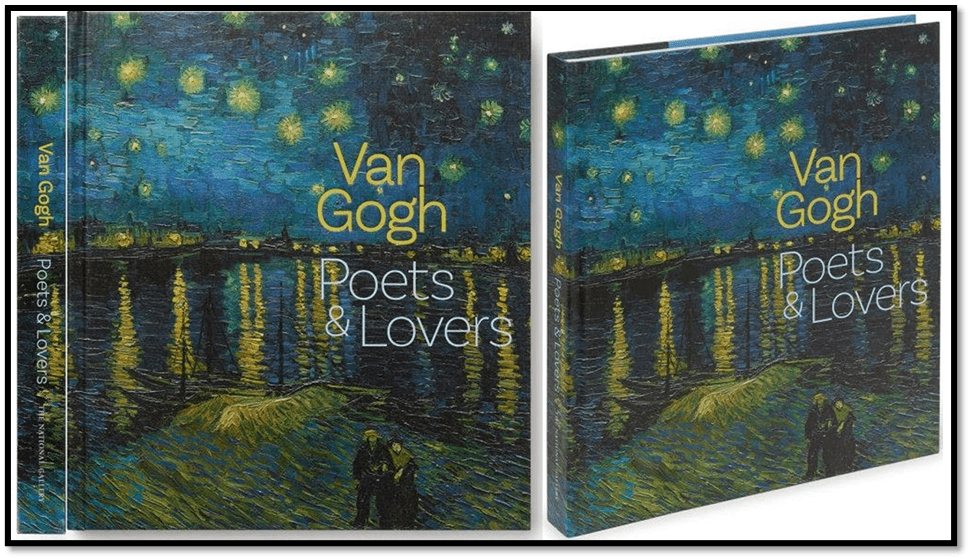

I wondered why given that I would continue to be astounded by seeing examples of Van Gogh art not previously known to me that the book designers chose to use one of the best-known (of course best known because it is so beautiful) on the covers of this extremely handsome book:

That picture Starry Night over the Rhône (1888) can be justified as being there to attract buyers to the catalogue precisely because, though so famous, it is difficult to see in the UK, being a rarely lent item from the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. Moreover the editors and curators clearly agreed that this painting best illustrated, not least because it immediately recalls The Stary Night (1889), equally hard to see because in The Museum of Modern Art in New York. That fact does lend itself to a more easy understanding of one of the bookmark themes of innovation that that this exhibition and catalogue emphasise, the notion of the decoration, a concept only completely to be understood if we stop thinking of Van Gogh as intending to create single paintings to which we respond entirely on their own standing, independent of comparison, with other work by himself or sometimes by people with which he considered himself working in collaboration for a collaborative outcome judged across a number of cognate paintings and studies.

However, if this was the intention it is not one discussed with regard to these paintings. Starry Night over the Rhône is discussed part of a possible decoration, but with a less obvious (and therefore more exciting to me, example; the painting known as The Irises (1889). I will return to the reason why. But before moving on, I wonder to myself here, if the decision to use Starry Night over the Rhône may have been a mistake. It does nor propose the new to us. To use more controversial a picture, such as that suite from the from Saint Rémy Garden with their tortured extremes of colour flows against each other, which even Van Gogh thought weird, would have made a point about an innovative take on the art better.[2] Or better still use The Tranquetaille Bridge (1888).

Julien Domercq introduces this idea in a splendid chapter focused on the use of tones, shades and cognate and colour-sense-based variations of yellow and orange, but not solely on this for the aim was also to associate place with emotion. Domercq discusses this in relation to the suite of paintings that Van Gogh prepared as a decoration, sometimes thought of an assemblage or coherent installation to use modern terms invoked in the catalogue by some of the writers there. The intention was to create a unified approach to the look of The Yellow House interiors but not solely in terms of the usual meaning of the word ‘decoration’ in English[3]

Primarily meant for Gauguin, who responded extremely positively, based on his collaboration on colour expression with Émile Bernard, they were also intended to be seen by Signac and Seurat, but no-one knows if they were indeed actually seen but by very few in The Yellow House. We know that Vincent’s art-dealer brother, Theo Van Gogh saw them but even he, according to Marrin Young, in one of the finest chapters in the book, ‘left no record of his impressions of the decoration’.[4]

This conception of a décoration is essentially seen as part of Van Gogh’s ambition to fulfill the task named, again obliquely, in the famous phrase in which he calls himself: ‘an arbitrary colourist … I paint the infinite’, quoted by Homburg as the overall introduction to this catalogue. Note here how we moved from consideration of colour design to meanings yearning elsewhere – sometimes to an overall capture of the essence of Provence but here well beyond that time-space towards ‘the infinite’.

Marnin Young (2024) ‘”Unity is Strength”: Van Gogh and the Exhibitions of the Avant-Garde’ in Cornelia Homburg (ed.) op.cit., 113 – 128. In my view ‘one of the finest chapters in the book’.

Marnin Young takes up the theme of the décoration and links it to the project of many post-Impressionist painters attempting to find a way out of a traditional view of painting as focused on the single work-of-art by creating series of a form of curation in exhibitions that emphasised commonalities between paintings and studies. One of the innovations indeed, it is suggested is to relax the distinction between a study or a ‘tableau’ (the conventional named for a finished painting ready for hanging. In Van Gogh the aim of the work in Arles was to create an assemblage whose overall effect is to show Provence as it is – as a spiritual and not just physical reality, and its means of signifying its serial purpose is through the use of a dominant colour, like the yellow / orange of sunflowers that would associate the common and visible phenomenon with its association with a series of meanings stretching into the infinite – from the Sun to the eye to God, to the arbiter of time and distinction between things.

Now as I write this I am aware of the danger of extrapolating too far from what some of the writers, and their emphases vary, say about Van Gogh’s innovative intentions with regard to art. They do not say this was a sole creation – it matched that of others, many already mentioned and it had connection to what the writers see as a tradition located in the idea of a Poet’s Garden, inhabited by the possible infinite associations of Arles to the basis of history, religion and art, from which perspective Arles could become visible (in some infinite perspective like that which showed Augustine the ‘City of God’) as the spiritual-cultural capital of Provence. I will talk later about poet’s gardens for it links work based not only in Arles’ public parks but also the garden at the asylum of Saint Rémy-de-Provence. I have travelled a long way from what the writers say about colour, but colour is essential.

But now let us return to a Starry Night over the Rhône. It was one of two paintings Van Gogh sent to be displayed at the Salon des Indépendents in September 1889. Van Gogh had intended it to accompany The Poet’s Garden (1888) as a contrast of background blues and greens respectively. Theo chose The Irises instead. We have to read between the lines here but it appears that Theo when he writes of how these paintings showed in the Paris exhibition recalls a debate colour and its power to attract from long distances and his view that Starry Night over the Rhône was badly placed because its colour could not attract and assemble with The Irises more subtle blues nesting in greens. Both Vincent and Theo clearly wanted the works to comment on each other by contrast and commonality. Even the critic Félix Fénéon seems to draw them together as colourist experiments that pull emotional punches : ‘His Irises violently shed their violet parts over their lath-like leaves. M. Van Gogh is a diverting colourist even in eccentricities like his Starry Night: …’.[5]

Let me repeat Young’s cautious warning about drawing all these paintings together and drawing from various conclusions – like the search for the unity that leads to the infinite in the artist’s intention or the painting that might appeal to the tastes of those not conventionally educated in art and therefore to a socialist art, both of which Young and other writers toy with, but not universally or consistently. Speaking of Roland Dorn, who Young tells us develops the idea more fully and with commitment into the hypothesis that Van Gogh meant works ‘to interact, developing a complex theory of pendants woven together, based on harmonies and contrasts of colour, tone, space and iconography’. Young suddenly grows cautious saying Dorn’s ideas remain ‘highly speculative’. though much of his discussion tends to show, as he develops it without full commitment, that ’works done in concert with the decoration have clearly defined aesthetic and iconographic relations that allow us to understand Van Gogh’s deeper concerns’. I wonder. I need to see the exhibition and its configurations of works with sets of paintings ‘in concert’, for that is to be expected from the catalogue, to decide. But this speculative feel makes the catalogue an exciting introduction to the exhibition and hopefully I will see Van Gogh anew.

The contents page of the catalogue is dominated by themes that tend towards the suggestion of a whole argument, starting with Homburg’s claim that this art was outlining, if only mysteriously, a new art of the future – democratic like Whitman, and based on iconographic sets that appealed to the way phenomena in the real world, like gardens (public parks as well), landscapes associated to the medieval past, the classics in poetry and paint (his gardens are peopled with memories Van Gogh invokes explicitly of Petrarch (who lived for a while in Arles), Dante especially, and the Greek and Roman past of Arles (of the Roman especially that of early Christianity – even if the symbols are ripped from, their conventional meaning), love, flowers and a theory of art as collaborative and communal (the décoration) and synesthetic in its symbols of the person and iconography – hence gardens (so central to iconography of all traditions written and visual). Hence Van Gogh’s studies and tableau taken together form holistic meanings in which scenes of macro- and micro-landscape (the latter in towns or parks or gardens) confound with the purposes of the portraits to develop iconic symbols (Poet, Lover Bonze – mystic – and purveyor of lullabies) of the artist as Seer, in the manner of Thomas Carlyle, whom Van Gogh read.[6]

In the light of some excellent work here perhaps someone should have guided Michael Glover’s chapter on poets – which has useful hints on Van Gogh’s reading including his pull to Walt Whitman as democratic artist to go beyond seeing Van Gogh as attempting to outdo Keats’ To Autumn in creating art that insists ‘because youth passes away, its sweetness, its fruitfulness have to be snatched at, gorged on’. [7] Such rhetoric belongs to the Van Gogh I already know from those who merge him into the late Romantic and early Victorian poetic tradition up to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in England. The Van Gogh I find in the other writers is yearning for a theory in which intellect meets the goal of the artist to evoke, sensation and feeling – a poet with ideas about the world and changing it through art. Cornelia Homburg’s Introduction is a more than ideal summary of this as a whole. Her analysis tends to show the painter trying to combine the effects in composition of subject, colour harmony and contrast, musical passages of meaning across pattern to reproduce the spiritual as human and available to all human beings. She quotes the following:

I’d like to paint men or women with the that je ne sais quoi of the eternal which the halo used to be the symbol, and which we try to achieve through the radiance itself, through the vibrancy of our colourations.[8]

Her analysis of Van Gogh’s shifts from motifs like the Sower and The Reaper (symbols of life and death respectively descending in French visual art for Van Gogh from Millet) to higher ideas like that of the Bonze (or mystic monk) in Zen Buddhism are beautiful and to me convincing. Judy Sund is equally brilliant in teasing out from paintings of public parks the mix of personal and ‘eternal’ associations mediated by medieval poetry between the Biblical Gardens of Eden and the Song of Solomon to the democratic urgency of public park building in the nineteenth century in order to democratise leisure and access to nature. The analysis of the locus amoenus (‘delightful place’) in medieval poetry is masterful.

The Poet’s Garden – Public Garden at Arles (1888) These lovers inhabit a world of coloured light and shadow.

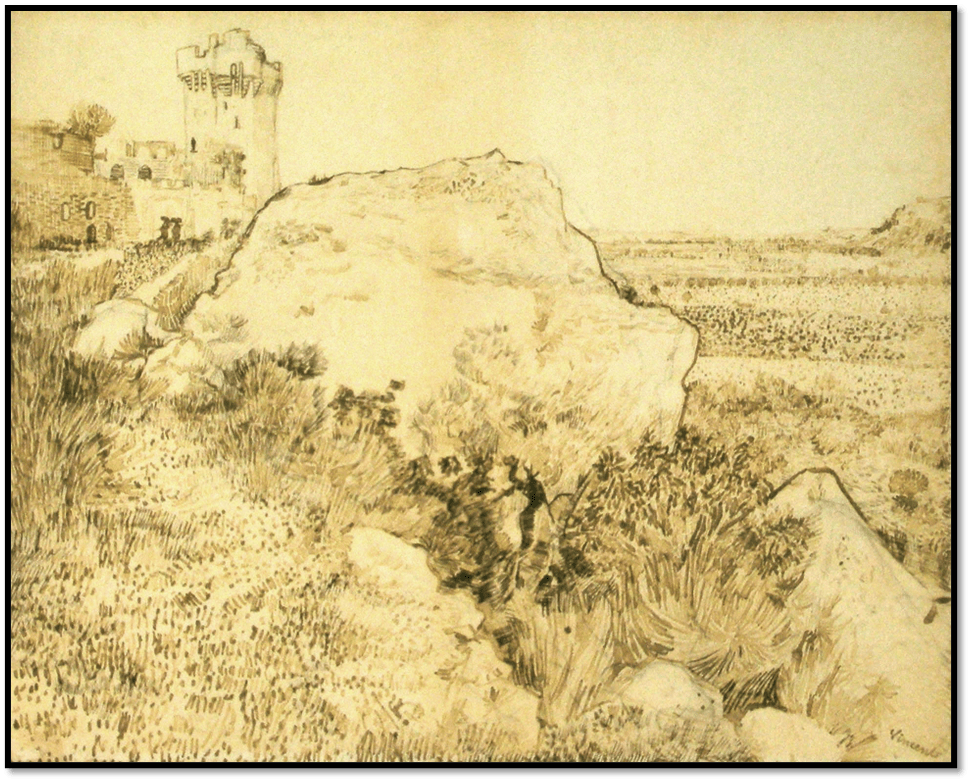

I will look out though for the Montmajour drawings discussed by Julien Domercq for Julien’s observation that these bind in feelings about the meanings of sex and love convincingly tie them to Van Gogh’s reading of Zola’s The Sin of Abbé Mouret, which is a ‘modern reworking of the Fall of Man that Van Gogh had already referenced in the early part of the 1880’s and set in the same scene of ‘Le Paradou’ at the top of this hill. What Domercq insists upon is the flowing together of ideas of sensation, ethics, feelings and ideas in the visible world such that it is interpreted complexly through these filters. I have the Zola on my Kindle now in the recommended translation in the catalogue. Have I time I will read it.

Can you see fallen nature here? Hill with the Ruins of Montmajour (1888)

I have deliberately held back from the paintings in this blog because I want the one I do after seeing it to be a fresh as the new perspectives offered in the catalogue can make it. I have not even summarised all the ideas in the catalogue. I do recommend it. It is a stunning work of the right kind of scholarship – one that is not afraid of venturing beyond traditional paths and conventions.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Cornelia Homburg (2024: 19) ‘Art of the Future’ in Cornelia Homburg (ed.) Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers, London, National Gallery Global Limited, 15 – 43.

[2] Those pictures are discussed in Judy Sund (2024) ‘Cultivating His Garden: Van Gogh in Saint-Paul de Mausole’ in Cornelia Homburg (ed.) op.cit: 159 –170.

[3] Julien Domercq (2024) ‘Sunflowers: Still Lifes in Arles’ in Cornelia Homburg (ed.) op.cit., 99 – 109.

[4] Marnin Young (2024: 122) in ‘”Unity is Strength”: Van Gogh and the Exhibitions of the Avant-Garde’ in Cornelia Homburg (ed.) op.cit., 113 – 128.

[5] See for this information and the cited quotation, ibid: 124f.

[6] See Renske Cohen Teervaert (2024) ‘Poet, Lover, Bonze, Lullaby: Symbolic Portraits’ in Cornelia Homburg (ed.) op. cit: 173 – 184

[7] Michael Glover (2024: 194) in ‘The Painter and His Poetry’ in Homburg (ed.) op.cit: 185 –194

[8] Cornelia Homburg, op.cit: 40.

My timetable as I coloured it:

6 thoughts on “The current Exhibition at The National Gallery promises to make you see Van Gogh differently. I see it on Thursday 25th October I read: Cornelia Homburg (ed.) (2024) ‘Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers’.”