Alim Kheraj of GQ magazine starts his interview regarding Our Evenings (2024) with novelist Alan Hollinghurst with a question about the ‘distinct first-person narrator’, asking: ‘How did that voice develop?’ Hollinghurst’s answer gives the reason why he thought a first person narrator was ‘inevitable’ because the events must be seen by someone ‘racially distinct from myself’, but also why such a choice in narration has advantages with regard to the novelist’s (and readers’) relationship to his central character. He says that even if the ‘first person’ narrator has a ‘testifying force’, it ‘is also filled with the omission of not knowing everything. That’s the fascinating thing about the first person’.[1] This is a blog on Alan Hollinghurst (2024) Our Evenings London & Dublin, Picador. It is a preparation to hear the author read and speak, interviewed by Tom Crewe at Durham Book Festival at the Gala Theatre on Sunday 12th October 2024, 7.00 p.m.

It is useful to start with the full quotation I cite in my title from Alim Kheraj’s interview, so here we go:

Because I was principally going to write from the point of view of someone who was racially distinct from myself, I couldn’t write it in the third person because to do so would’ve been to assume a kind of authorial omniscience about this person. And I thought the value of the experiment for me would be to do it in the first person, which obviously has a sort of testifying force to it, but is also filled with the omission of not knowing everything. That’s the fascinating thing about the first person.[2]

I began to think about Hollinghurst’s choice of ‘someone who was racially distinct from myself ‘ as first-person narrator when I did a brief blog on Hollinghurst’s translation of Racine’s tragedy Bajazet, given the appearance of the play in the novel’s prelude (read that short blog at this link).

There , I came up with no good reason that Hollinghurst might evoke this text from his memory, if he indeed does, but I wondered if it had much to do with interactions between love and/or sex and socially defined sex/gender on the one hand, or the advantages of writing of different cultural and racial origin in characters because of Racine’s discussion in that particular play of the effects on him of writing from ‘the point of view’ of persons who were racially distinct from him and the culture of the seventeenth-century royal court at Versailles. In fact, I think paying too much attention to Bajazet probably will not help progress our understanding of the novel, though I find its inclusion interesting.

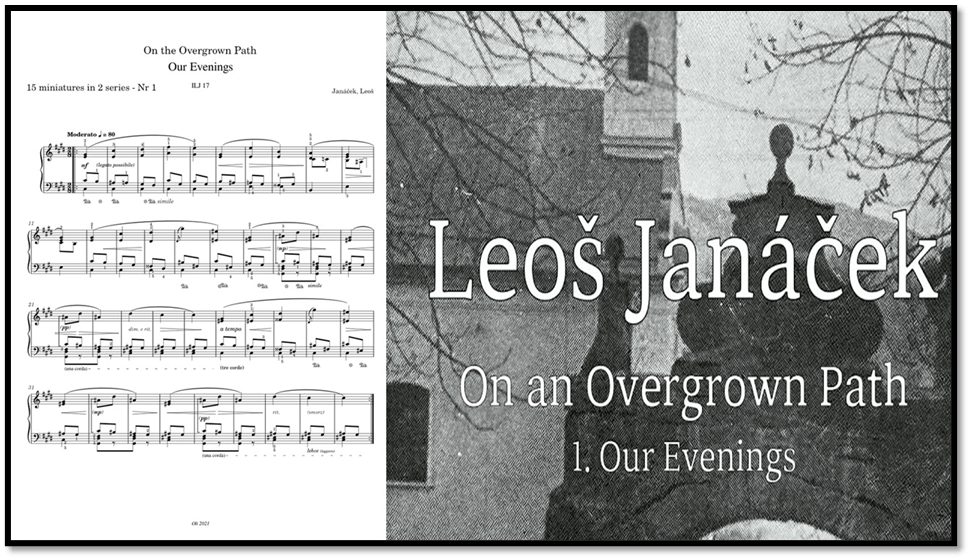

Racine is there anyway jostling with many other highlights of European literature in English (counting translations as that too) that begin to dominant David Win’s understanding of the world: central voices of an English tradition. He does not name all of these but, later, his husband does add some: such as ‘Hopkins sonnets, “Felix Randall”, “Spelt from Sybil’s Leaves”’ because ‘they were part of him and always had been’.[3] From his own testimony we could add the music of Vaughan Williams (very English) and Janáček, the poetry of Matthew Arnold and William Butler Yeats, as well as the Elizabethan and Jacobean playwrights, scattered with plays of the contemporary moment .

All of this cultural baggage has much to do with the bits of David Win, the narrator and protagonist of the novel , that are something very like Alan Hollinghurst but for the dark brown skin, which most white people who interact with him speak of as ‘very dark’ (I take the exact words from the lascivious older queer gentleman Derry Blundell). Blundell too is an English relic with a taste for beautiful Burmese young men, like a singer he once had sex with. Lately widowed by his male partner but with clear memories of Cecil Beaton, Derry invites him to his ‘secluded old house’ fronted by a statue of Boadicea (as English as you can pretend to be). They eventually fall into ‘rather unbuttoned’ conversation and thereafter Dave allows the old man, not without obvious readiness and hardness, oral sex.[4] On the way to this visit the taxi-driver, unsure this man knows what he might be letting him in for asks: ‘Been in England long?’

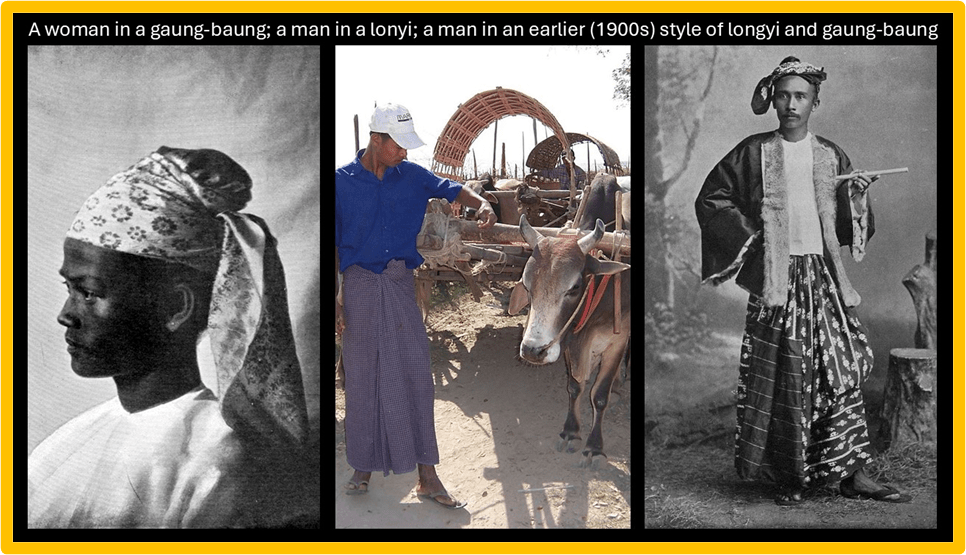

Derry himself amidst his clutter of memorabilia of ‘soldiers and naked wrestlers’ also has a bronze ‘of a Burmese boy, bare-legged in a tucked-up longyi, that was very like things I’d found on my drifts through the unpeopled Far Eastern Cultures wings of large museums’. The mix of what is noticed and recorded in this journey is a perfect illustration of what Hollinghurst means I think about the way Dave Win’s narration of experience allows for the testifying effect of consciousness thoroughly, almost exclusively formed, in British (pre-Brexit) cultural expectations but aware of that space – ‘unpeopled’ because the interest in the Far East is so relatively low in museums in the West we are told, – where lies the ‘omission of not knowing everything’. But the eradication of Far Eastern populations in ‘unpeopled’ in this sentence lingers on uncomfortably.

I think in this novel Burma, and Burmese things and persons form a kind of absence (an omission) that David Win is never allowed to fill and must live in (and, as I suggest later, may not WISH to fill in). It is more convenient that Burma and all it stands for truly live only within an unuttered outsideness to his experience in time. Being Burmese either attracts attention from others, for some mixed sometimes with racial distrust, for others (like Derry) with desire for the exotically different, or is rapidly pressed into an knowledge of him people act as if to which they are blind.

Invited to the house, named Woolpeck, owned by the benefactors of his Exhibition scholarship at Bampton public school, Mark and Cara Hadlow, Dave accidentally meets Cara’s Uncle George, a man also bereaved of his male partner but living on in the house, who says to Dave that he is ‘not absolutely clear where you’re from’. Informed by Dave that he is at school with George’s nephew, Giles, the old man is eventually forced to make it clear that his question referred to racial not local origin: ‘”But your parents,” George said, “not English”. Finding out that his mother is English, George asks further, though without fuss, how it comes that he lives only with her. Dave finds one of the many fictions he has to answer the question, because he has neither knowledge of his father nor, it is apparent, Burma: ‘“The thing is, you see,” as if I were an old man explaining to a child, “my father was from Burma, but I’m afraid he’s dead now.”’[5]

This is a most delicious moment as Dave takes on one of his many live performances – ‘as if’ fictional roles – that try to invert the power deficit that questioning about the ‘omissions’ from his personal narrative leave him in, in relation to the questioner’s superior status. George however is not a man without knowledge and tolerance of difference in the world and merely concludes that Dave is ‘half Burman’. The term ‘Burman’ is a more accurate identification of a majority racial grouping in contemporary Myanmar, whereas ‘Burmese’ that Dave uses in preference later is used to refer to any inhabitant or object associated to Burma. That this is implicit only if you know the distinction, which Dave does not at this point appear to do (the word Burman is taught in terms of race (inaccurately) later in his public-school experience) is part of the domain of first-person narrative omissions – since no-one can report a fact of which they do not actually have any awareness, or say they do not.[6] Talking to a boy, Manji, from the then city of Bombay, Manji’s knowledgeable talk about India is met by Dave’s dry responses describing a thoroughly English thing as his background experience, ‘something boring like Christmas’. That filling of a gap or omission with a half-truth is typical. Rather than explore a memory in which Dave has the character of a being that is not defined by one racial boundary (nor one sex/gender boundary we shall see) Dave plumps for the conventional ‘English’ account of life. It is beautifully written. Viewing the grim thoroughly English architecture of Bampton, the images he sees outside him:

…blocked out my own frail images, first newsreel flicker of faces. There was the shiver, before the swirl of a skirt like a ball gown around my bare legs, of something not in fact a skirt, a longyi for a child, in pink and blue tartan, wrapped round and tied, …[7]

What stops David exploring this image with Manji? The reason the exploration is end-stopped seems an amalgam of the fact that the frail images he conjures are conventionally unclassifiable by norms and hence must be omitted, at least from public discourse that other boys might hear about. At home Dave learns that the ‘Burmese treasures’ in his mother’s ‘teak sewing-box … (one of the few things that she had brought back from Burma’) with its ‘sharp far-off odour’ when opened contains her longyi and ‘six-foot-long gaung-baung’ that he still somewhere remembers ‘were worn in Burma by both men and women’. Every boundary is crossed in between the opening and closing of a box, and knowledge of both its outside and inside. This boundary crossing even characterises Dave himself as a young boy in which self and Other (boy and mother/brother/lover), male and female intermarry between and within distinct sex/gender categories: ‘Mum fixed me up in the gaung-baung and sat me at her dressing table, me in love with this beautiful self, like a brother, in the mirror, Mum tensely admiring me too for a minute, and then quickly undoing it’.[8]…

Likewise in school geography classes, even the little knowledge Dave has of the country (that it contained ‘many different peoples’ is as ‘’mixed up, and muddled in my head’ as the people are ‘mixed-up’. That ambiguity is even provided in the sentence.[9] If Mum undoes almost immediately all the memories she facilitates for a delicious moment wherein Dave experiences a less formally boundaried ‘alien’ world, people do the same with any slip she makes that might validate that ‘far-off’ past and space that is Burma: ‘Ruddy hell, Avril, we’re not in Rangoon now’.[10]

At Oxford when Dave sits his History finals, he walks out of the room. There are lots of possible causes – being in love with a guy who doesn’t love him ‘in that way’ seems to be the one people settle on – but in the text it seems more to do with the way that the examination demands from Dave the display of a public knowledge of Burma:

… I had a broody feeling that Burma, which was part of the Indian empire till 1937, was my private subject, on which I couldn’t and shouldn’t be examined. … But really my feeling of possessing the place was a well-guarded ignorance, an unbreakable reluctance to learn.[11]

His thoughts at that moment turn to playing the thing he is good at, a gentleman plutocrat’s ‘parasite’, Mosca in Volpone, of which more later perhaps. Later, quizzed by students, his usual response to friends or informal interlocutors changes from saying he has never been to Burma to ‘we might go, mightn’t we, Richard’, invoking his husband’ s complicity with a conditional agreement easily retractable later but eventually getting annoyed that they should think there is a British Burmese community, or set of actors to give him support and who confuse him a half-Chinese actor.[12] Yet, as I say later, he never tries to contact that community, such as it is.

Moreover, on his mother’s death it appears that even the Burma of his fictional imagination might turn out to have no validity or reliability inbuilt for his mother’s friend, Jane tells him that the reason she rarely spoke of his father to Dave was that ‘she didn’t know anything about him herself’ and had only seen him ‘two or three times’. The absence of Burma from the novel becomes here complete in it’s the purity of its expulsion – from the present but also the past and future.

But this is not because the novel has failed to testify to the fact there might be a Burmese point of view but only to show the forces that fill that point of view and its stories with ‘the omission of not knowing everything’, some of them perhaps willed omissions. Even at the end of the novel no-one, not even Richard Roughsedge, for instance (though his very English husband) knows that distinct point of view, and even Dave struggles to find even fragments of it as his memory deteriorates further. My own feeling is that such points of view can never be complete. Of course an omniscient narrator might think that they knew more fully what the first-person narrator did not or knew only partially (or refused to recall) but this is the very step Hollinghurst resists as a possible appropriation of Burmese knowledge by a man definitively not Burmese.

Later, in this blog, I will suggest that David is always reluctant to carry into acknowledged learning things he does not want to understand or whose understanding is better, or more conveniently, omitted. For instance, he, his mother and her female partner, struggle over a Latin inscription to a sundial in the garden of his lesbian parents’ home. Dave says he will ‘look into it for you, ladies’. We do not hear of the sundial again till, the ladies lost to us and him, the house is sold, and where Richard, at a stroke, identifies the quotation as from Cicero De Senectute: ‘slowly, without sensing it, we grow old’. There are good reasons Dave resists learning to translate this phrase. Because though Dave Win always seeks to win from everything in life, what actually wins is always mortality (ageing and death), though he resists that, unlike Cicero in De Senectute, in the same way as he resists a truly Burmese point of view.[13]

This pragmatic view of partial telling of what one will not see or tell whole is played out in the theme of the novel that deals with the role of acting and performance in life, including storytelling one’s magnum opus, your life as a whole. Acting and performance come from an art that is never in the end about one dominant point of view, as in the novel employing an omniscient narrator’ but many multiple ones, some of which have to be inventions. The main point in acting is deliberately avoiding mauvaise roles and as many small parts as possible.[14] Meanwhile, all Dave Win has, in terms of a perspective formed by national cultures, is an ambivalence about Britishness. And it is this ambivalence the novel excels in demonstrating.

It is most prominent in the attitude of Dave to Giles Hadlow. It would be a mistake to not see the ambivalence here because we have lived through the history of bullying authoritarian politicians like he through the period of both Brexit and COVID and the decline of arts funding, for all of which Hadlow has a governmental role in the novel. When we first see Giles it is as a big boy placed on a plinth – a trigonometry point in fact – so that Dave has to look up at him. The point of looking up at him should not be lost. Dave says he ‘squinted up at Giles on his pillar, handsome with the sun behind him. He was only three months older than me but growing faster, and impressively big’.[15]

Dave’s aspiration to Giles’s masculine power speaks through this almost as if the English boy were the Apollo that illuminates him. Dave balks at Giles entitled assumption that he has a right to sex with Dave, as the older boy and son of Dave’s benefactor but this is not because there is no sexual attraction. On the second night Giles comes to Dave’s bed in Giles’s parents home, he decides against shouting out a refusal of sex to Giles because – although the sense impression in the sentence too is merely momentary – ‘his warm hard pressure against me in bed was different from the roughness of him in our fights out of doors’.[16] There are moments like this early in the novel that are eventually drowned out by the bully and the authoritarian Giles easily becomes in his noisy government helicopter, adopting the role gifted to him as the son of a landowner used to power and control. Even as a boy Giles plays games that Dave would rather not be part of: ‘undermined from the start by a feeling that we were too old to be playing them. And his violence when he caught me, his Chinese burns, and bending my fingers back, made me dread them too’.[17]

As a man Giles is a monster, and, as Dave tells Richard, just as at school he was ‘a cheat and bully, and I must say very good at being both’, it has stood him in good stead as Tory minister: ‘He cracked the whole thing early on’.[18] The important thing the novel sometimes seems to be saying is how you play the game and hence the central image played by the game ‘Plutocracy’, played in Giles’s home early in the work, for even socialist theatre groups have to give in to ‘plutocrats’ they condemn.[19] Dave’s first book The Stage is All the World (the inversion of Shakespeare’s ‘all the world’s a stage’ and putting in a prior claim for art’s right to interpret the world rather than vice-versa as in the Shakespeare) can be seen as a preparatory stab that the imaginative creation of worlds illuminates real worlds and unites partial perspectives, as does Bajazet by the way. The only sin here is bad acting, like ‘Olivier blacked up’ as Othello.[20]

His second book, the magnum opus, is a ‘continuous traffic between “confident memory” and “honourable invention”’.[21] And not all the invention or the memory is confident or honourable. Dave certainly misses out f his account of himself the role of a committed affair with the young queer theorist Calvin in his life, whom he leaves for Richard to care for.[22] And there is in Dave too something of the mountebank that his hero Mosca enacts in Volpone, a man who knows how to live nicely from plutocrats and chops and changes with the weather, and even the sexual whim – that takes him on the journey though potential and real lovers (it’s a bumpy ride): Giles, Mr Hudson at school, Marco, Jeff, Nick, even Derry and, more seriously, Chris Convey, Hector, Richard and finally the shadowy Calvin. Like Mosca he can perhaps:

… skip Out of my skin, now, like a subtle snake, I am so limber. O! your parasite Is a most precious thing, dropt from above, Not bred 'mongst clods, and clodpoles, here on earth. I muse, the mystery was not made a science, It is so liberally profest! almost All the wise world is little else, in nature, But parasites, or sub-parasites.—.. ….: But your fine elegant rascal, that can rise, And stoop, almost together, like an arrow; Shoot through the air as nimbly as a star; Turn short as doth a swallow; and be here, And there, and here, and yonder, all at once;[23]

Dave Win sounds like an English man even in name, and to all purposes Dave tries to pass as a white English man, though boys called him ‘wog’ at school.[24] The whole theme of passing is cleverly dealt with in the story of a Trinidadian painter called John Constable (the point is obvious). Dave turns it into a cruel joke:

“Probably not much scope for confusion.” I said, and the joke was fresh for me, at least. I turned and looked at the room, almost as if congratulating them.

Dave often looks for audience approbation though he pretends sometimes he doesn’t read his reviews. Richard Roughsedge is a kind of tragic character as the man who must complete the story of the semi-fictive Dave Win. For Dave Win will always win. He may be hurt by people thinking there is a Burmese community in Britain but he doesn’t seek them out, such as they are, yet he knows they are there and where they are. He has an eye for the main chance. The relationship he has at school with English-teaching schoolmaster Mr Hudson is a case in point of his abuse of others.

He first learns of Hudson from Mark Hadlow.[25] By the time he reaches the sixth form he has become the Secretary of Hudson’s Record Club and seized the chance for private evenings – one of the many of ‘Our Evenings’ with him. Caught on his way from the room of Mr Hudson, at Bampton School, by another master, Dave explains that he is secretary of the Record Club and was planning with its director, Hudson, the programme for the next event. Asked what they heard this evening, Win says it was Janáček, On An Overgrown Path. Yet he holds back one piece of information, at least one for he holds back so much in this novel; that they heard one piece of the whole collection of pieces in particular with its own title: ‘The title of the magic little movement, ‘Our Evenings’, I kept to myself , as a private matter’.[26] (Hear that piece [“Naše večery” (Our Evenings)] at the link here) . The evenings of course drop off and Hudson is a revealed as a sad man tied to his mother writing letters to schoolboys where he says nothing of his obvious feelings. Not for Win, this loser.

Our Evenings, Richard Roughsedge eventually decides to be the ideal title of the magnum opus. Discussing that title, Richard gives to the posthumously published work that this novel pretends to be, we read in Dave’s account how Dave christened his evenings with Richard with this title, but not these evenings and with this man alone. He has them with Chris Canvey and names them as such.[27] Other people have other versions of his ‘our evenings’. I think the irony in the sentence Richard finally comes out with when he sees the multiplicities implied is beautiful. Richard says of it, the apparently simple ‘Our Evenings’: ‘I’m not sure yet if the possessive pronoun is a solace or an ambush’.[28]

And when Dave was in charge of his narrative we know he angled it in such a way to look significant. I love this early image: ‘I looked across at the mirror that reflected the bed, and seemed to frame us in a larger and more beautiful space’.[29] Even the Lady of Shallot gets her comeuppance from a mirror in which she abstracts her significance. The dangerous thing is to try and make it real and turn away from the mirror. There is so much more to say but I need to stop here. Perhaps it is worth though distinguishing how I read this novel in a different way to the superb Alexandra Harris in The Guardian. Here are two brilliant paragraphs from her:

… Dave retains a lifelong respect for …., his sponsors, who are lovers of the arts, people with money “who do nothing but good with it”. Their house, Woolpeck, is a place of beauty, encouragement and refuge, one that Dave revisits in memory on “little mental occasions” that no one else could guess. Going on like frame narratives around the edge, these long enmities and attachments are touchstones, as the decades pass: measures of how imaginative life might be fostered and how it might be squashed under the heel.

…. A summer holiday on the Devon coast gleams with the beginnings of erotic excitement as the 14-year-old watches, mesmerised, “the shifting parade of known and unknown men”. It’s bravura writing, quietly done, generously varied in tone as the Fawlty Towers comedy of hotel routine accompanies the beautiful seriousness of desire. It’s collegially reminiscent of other literary comings-of-age and seaside longings, but compellingly fresh page by page; no Proust or Mann or Alain-Fournier would have sent Dave off to the gents behind the esplanade.[30]

In both of these paragraphs Harris sees Hollinghurst as a consummate but different kind of artist. I agree with that. Where I part company is in the omission of Hollinghurst’s ethical assessment of queer lives that the author nearly always applies in his work through the ironies implicit in unreliable narration. I hope I have illustrated that. In that he is like the great tradition of the novel – like Henry James in particular with a less obfuscating turn to his syntax.

This is a novel of very great genius. A genuine contribution to the queer novel and a shout out for a more ethical world, not ruled by plutocrats and their ‘parasites’. But it is kind in the process and we all have to be that.

Read! Read! Read!

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Alim Kheraj (2024) ‘Interview: Alan Hollinghurst on Our Evenings, his most daring and political novel yet’ in GQ Magazine [online] (7 October 2024) available at: https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/article/alan-hollinghurst-our-evenings-interview#:~:text=Our%20Evenings.%20,%20his%20most%20daring%20and%20political%20novel%20yet

[2] Ibid.

[3] Alan Hollinghurst (2024: 481) Our Evenings London & Dublin, Picador

[4] Ibid: 309 – 321

[5] Ibid: 28

[6] Ibid: 97f, where he wonders if ‘the Burmans themselves wrote books about their country’.

[7] Ibid: 84

[8] Ibid: 70

[9] Ibid; 96

[10] Ibid: 77

[11] Ibid: 235f.

[12] Ibid: 447f.

[13] Ibid: 194 & 457 respectively

[14] For mauvaise roles see ibid:341

[15] Ibid: 16

[16] Ibid; 49

[17] Ibid: 17

[18] Ibid: 273f & 403. respectively

[19] Ibid: 53 – 57, & 264 respectively.

[20] Ibid: 254

[21] Ibid: 485

[22] Ibid: 486

[23] Ben Jonson Volpone or The Fox Act 3, Scene 3.1 available at: https://genius.com/Ben-jonson-volpone-or-the-fox-act-3-scene-31-annotated The last few lines in Hollinghurst 2024: 231

[24] Alan Hollinghurst, op.cit: 143

[25] Ibid: 24

[26] ibid:176

[27] Ibid: 300

[28] Ibid: 487

[29] Ibid: 2

[30] Alexandra Harris (2024) ‘Our Evenings by Alan Hollinghurst review – his finest novel yet’ in The Guardian (Wed 25 Sep 2024 07.30 BST available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/sep/25/our-evenings-by-alan-hollinghurst-review-his-finest-novel-yet

2 thoughts on “Alan Hollinghurst says that even if the first person narrator has a ‘testifying force’, it ‘is also filled with the omission of not knowing everything’. This is a blog on Alan Hollinghurst (2024) ‘Our Evenings’.”