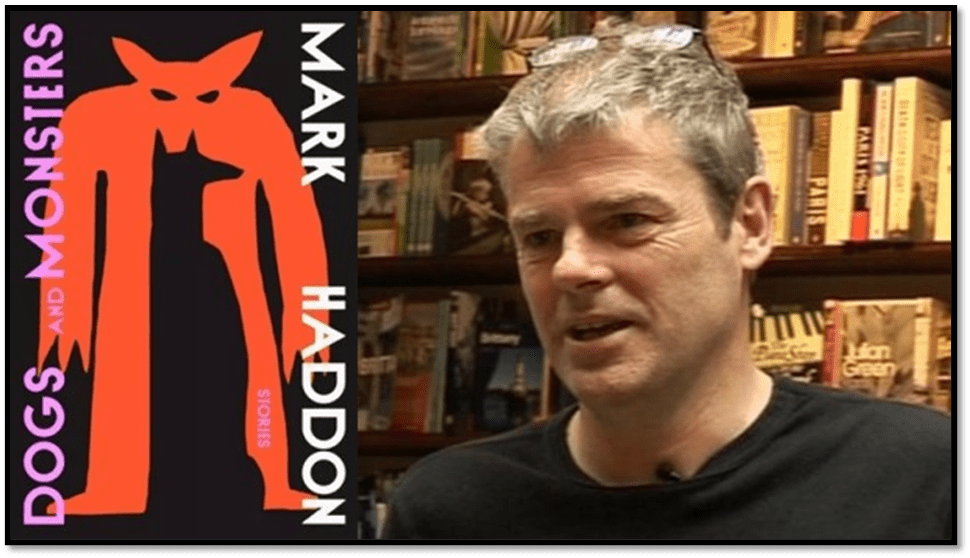

In the first story of Mark Haddon’s Dogs and Monsters (2024), named The Mother’s Story, a wily inventor and engineer, capable perhaps of only inventing dangerous fictions says of a story he is in the process of telling: “Much depends on it being a story that people will listen to greedily and be desperate to pass on”.[1] This is a blog on this volume based on retelling fantastical stories.

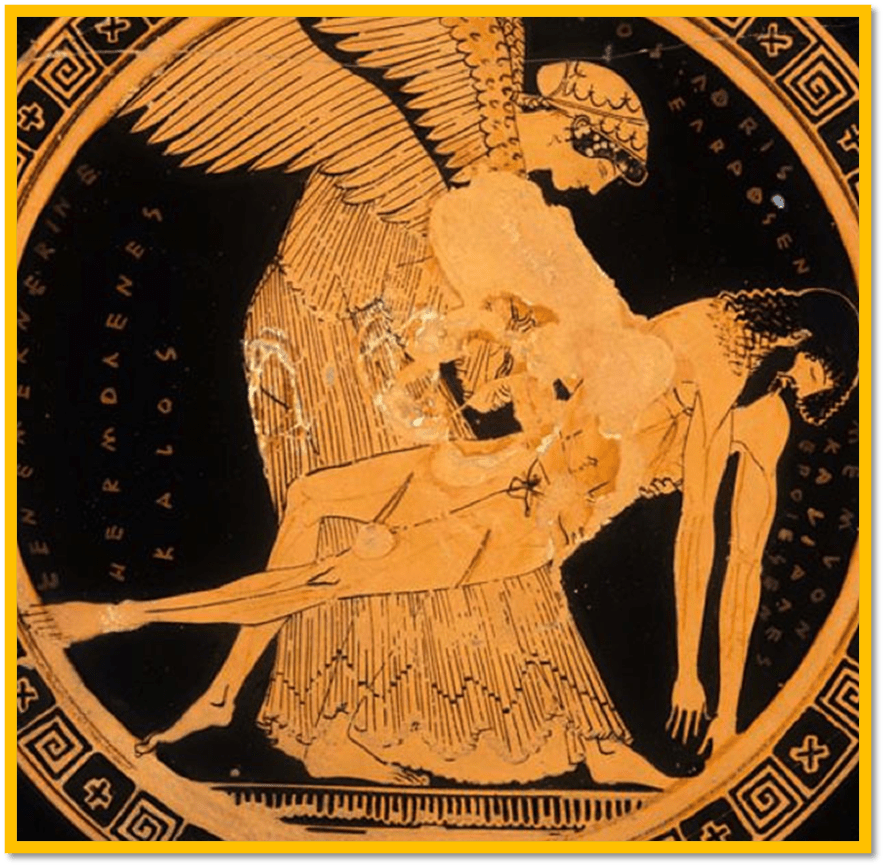

The basic condition of the claim of being a person is probably that of being, in the first instance, a human. But even if we were called upon to make that claim, it would be very unusual for us to acknowledge that a human is a species of the genus of animals. In the story The Quiet Limit of the World, the protagonist is addressed by a woman who visits him in hospital, and who has obviously been his partner and caregiver in his home, ‘her voice suddenly serious. “Who are you?”[2] The question could have equally been, since it takes the entire long story that follows to establish whom the protagonist might be, “What are you?” The answer might surprise us, for the character of the protagonist as an entity has undergone many hard-to-categorise changes. In other stories, the changes undergone by persons are even more extreme, especially the character, Actaeon, based on the mythological story of a hunter turned into a stag by the Goddess Diana, for the sin of seeing her naked, and torn apart by his own hunting dogs.

This last event in his life occurs on the ninth page of the story, where Haddon’s narrator says, ex cathedra as it were: ‘And this is where the story ends for Ovid’.[3] For the narrator, however, the story goes on (for a further six pages) to pursue the fate of the sub-species we call dogs of whom Actaeon’s hunting-dogs are a prototype. They are a prototype, the narrator suggests, because they too are now, undergoing ‘metamorphosis’. This happens in part because, perhaps, he muses, they have eaten a human being as their meat, and moreover a human who dies on the cusp of having been touched himself by the power of the divine to change the nature of the substance of the being of things with which they interact. The effect is that these dogs ‘are no longer entirely at home in themselves’: cast into the consciousness we assume to belong only to humans but which they now share. In fact, it is not just that these dogs now cast their minds into the future but that a psychological precondition of doing so has been acquired – an ability to think not just in terms of what HAS factually happened but also to what MIGHT happen, and with that goes the potential to imagine the counterfactual world of WHAT MIGHT HAVE HAPPENED in the past under different circumstances.

The discarded bone, the bed of straw, the plump rat skittering over the flagstones between kitchen and stables … these things will no longer posses the ability to fill the world to the brim. When the dogs dream tonight they will dream not just of hat has happened today and in the days before but of things that might happen tomorrow and in the days ahead’.[4]

In brief, they gain the capacity to be the tellers of stories as well as their central subject – and Haddon puts their successors – right up to the dog, Laika, the Russians sent into space never to be able to return – into a succession of stories (although, alas, they are all written by humans). These include the story of Buck in Jack London’s The Call of the Wild, Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles, Dora’s Jip in Dickens’ David Copperfield, Flush, the story of which real dog belonging to poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning is told by Virginia Woolf in her novel, Flush. And thence onto the implied stories of dogs in human visual art, whether that of Landseer, Goya and Uccello. There is a paradox here, for these examples only award animals the consciousness of retrospect and prospect, the memory of fact and its embellishment in the imagined counterfactual or fiction it takes to tell their story by virtue of the fact that their story is written through human not animal consciousness.

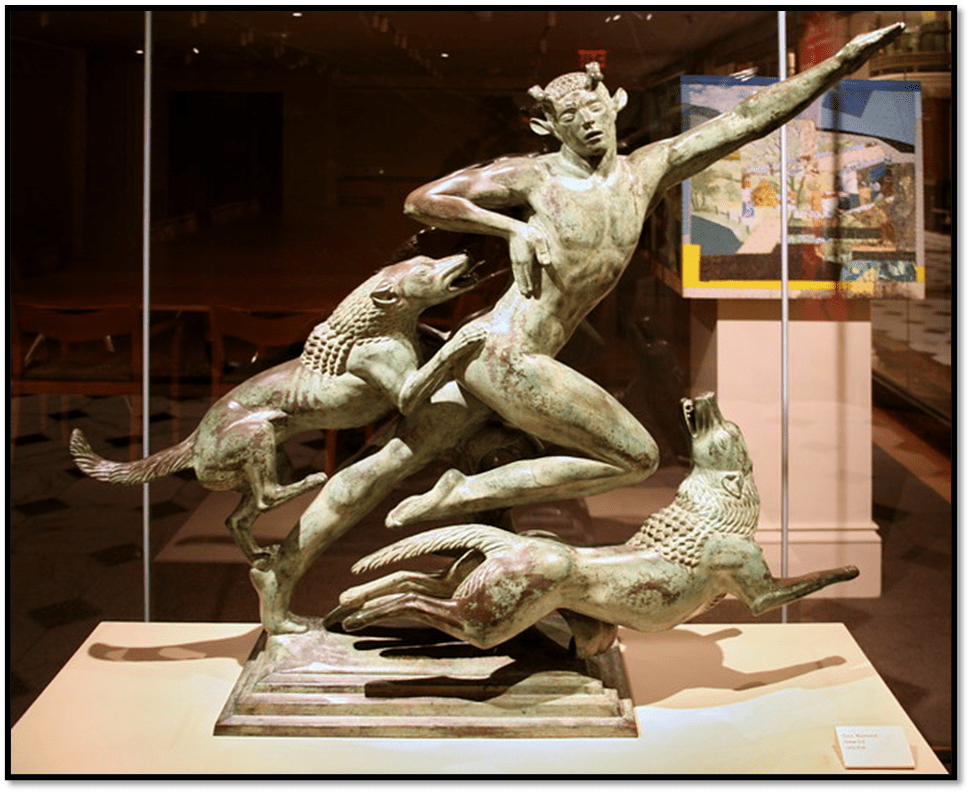

Paul Manship’s version

Ovid does not like Haddon enter into the consciousness of Actaeon as he metamorphoses into a stag, starting with the physical features such as antlers but not quite reaching yet (by the time he is murdered at least) the manner of thinking of a stag. As Haddon’s narrator says:

…if her were pure stag he might throw the dogs off, if every particle of his energy were committed to running, but there remains some small human part of him which cries out even in the privacy of his mind – Why is this happening to me? What have I done to deserve this? – and this is an indulgence an animal in flight cannot afford, when the mind must shrink to nothing and the body must be committed as a thrown spear or a falling rock.[5]

Story-telling may be performative (it has to be told and in some way enacted, if but by voice or the act of writing). However, it is also an means of engaging and entraining the nature of emotion, expressed either outwardly or inwardly or in a (possibly contradictory) mix of both. But though it is both of these (action and feeling) it must also be cognitive – it engages with thought even in its sequencing and perspective on events for instance. No stag could do this in flight and hope to escape the consequences of the delayed response in the body involved. But Actaeon is neither stag nor human but still on the boundary of being each or either – a liminal being. As Storm, his dog, sinks teeth into him he ‘cries out’: ‘“I’m human! Do you not recognise me?” But his lungs and throat and tongue can form nothing beyond that wordless, scraping bark’.[6] This last short sentence is full of irony. Even had this been spoken it is uncertain it could be understood, although Storm may have recognised the sounds of his master’s voice> However Actaeon still feels compelled to articulate it in language to his dogs as he would in an argument with a human being. Moreover though he produces a stag sound, it is no more intelligible to a dog than a human’s articulate language. The term ‘bark’ makes the point cruelly – for a stag’s ‘bark’ is not the same as that of a dog, though humans may use the same word for it.

Even the fact that all the dogs are named is significant. As Haddon’s narrator says:

Actaeon is the only human character to whom Ovid gives a name. Thirty-three of the dogs are given names. Some of them have their heritage appended too, as if they were Homeric warriors: … Ovid devotes more time to the dogs than he does even to Diana’s nymphs, only six of them are given names.[7]

This is more problematic than it sounds for what is implied is that dogs entered into the consciousness of themselves as the focus of a story, as narrators like Buck, for instance, but even as protagonists with an assumed point of view like Jip, mainly because of the human desire to make everything human consciousness touches upon the nub of a story and to tell that story. The sadness of the fate of the space dog Laika, is that, though she is aware of stories happening around her, she is never in control of those stories and will burn up in space to be ‘transformed into nothing more than the tiniest change in the colour of the rain falling on a single mountainside’ with no more agency in her own story than the zero quantity she started with.[8] And is not clear if anyone sees this ‘change in colour’ though the human narrator imagines it – in more control at the conclusion of her ‘story’ still than Laika.

Laika, (Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=793939)

Any thing that tells a story performatively (that is enacts its telling) and with the ability to see that story reproduced by others has control of it and can limit its interpretations and skew them, either consciously or less so, to those interpretations that favour themselves. This is the point that is made by the short story My Old School, which is very clearly a story about why we tell or do not take ownership of stories, our own or those of another, and retell them. For Nina Allen, reviewing the book in The Guardian, this story distinguishes itself from other stories of bullying in boys schools, such as that told by Roald Dahl, by ‘the confusion it generates in the mind of the reader: who exactly the bully is here, and how the truth of an event can be thrown into question by being perceived from a different angle’.[9] Allen does not go that step further in her review to see that Haddon is precisely a ‘master storyteller’, in her term, because he shows how the means of telling a story achieve mastery and dominance in a number of ways and not just aesthetically, but in terms of creating or responding to shifts of external power between characters whose actions also include the telling of stories to each other. That everyone tells such stories and that they contradict each other sometimes in effects of interpretation of fact or feeling is precisely why we are ‘confused’ by My Old School.

The unnamed narrator who tells the story from the vantage point of middle-age, tells first of the time of his residence in boarding school in 1976, and then of a school reunion in 2010. As a schoolboy he is very careful about to whom and how he tells stories, such as of that of the sudden death of his grandfather, a ‘cinema organist’. The story told by his parents about that death is anyway a partial lie, sanitised in the manner that it is common to do with stories of death told to young people, but they even tell it indirectly, though the schoolmaster Fairfax. The narrator shows that he knows, from Fairfax’s manner alone that he has to be careful not to retell the story in a way that might show him unable to cope with such things. Hence he locks himself into the toilets of the school changing rooms and there ‘cries’ to himself, as he feels he must.

Discovered crying , the boys taunt him and he wonders whether, if he ‘told them about my grandfather, it might make his lot better, if only this did not mean handing over ‘yet more private information’ that might become ‘another weapon’ used against him. The weaponisation of stories matters, yet even without adding this private information the basic story of his crying alone in the toilets ‘mutated’: ’The new version … was that I had been weeping because I was trying – and failing – to masturbate’. Because such a story spreads swiftly and widely in a place where such topics were fed from boyish fantasies and fears, ‘I immediately became known as Baby Cry-Wank’, or other heinous alternative names.[10]

Throughout the story, as Haddon allows the narrator to tell it, men use stories as means of increasing their own reputation for bullish masculinity by reducing their claim to it by passing that claim to another boy, or other boys, who act as scapegoat for the fear of emasculation in teenage boy groups. The entire dark undercurrent of this story lies in the link the narrator makes between his own deficient masculinity in relation to his father’s schoolboy love of fighting, and other violent competition, aware that he, as a son, was ‘more like my mother than him, unathletic anxious and often unhappy’, with little love of ‘rough-and tumble’.[11]

The story hangs then on how this narrator escapes bullying, and the loneliness that goes alongside it, by finding a substitute scapegoat – a new ‘mummy’s boy’. Good luck brings the new learner, Graham Meyer, to his notice and better still, contingent accidents give him power over ‘private information’ about Meyer’s family situation, from which retellable and mutable stories can be retold amongst the boys. Meyer is ideal because he is a ‘kindred spirit’ to the narrator, almost I think a double or doppelgänger, whom he ‘could see instantly was going to be bullied’. The issue is that both boys tend to identification as ‘feminine’ or babyish. Hence Fairfax, equating dealing well with stories of loss or emotional disturbance as ‘being a man’ precisely prompts the fantasies of which might happen to the narrator if stories start circulating in the school in which he is represented as weak, passive or vulnerable (as ‘girls’ are supposed to be in this toxic binary). And this is precisely the advice he gives back to Meyer when the latter tells him of is parents’ divorce triggered by his mother’s sexual affair with another man.[12] Meyer expects his story to be kept secret, for he too is aware of the consequences to his male self-esteem.

The pressure to let out that secret comes from the mutation of the two boy’s story of how the narrator finds Meyer in a tree and, as it were, rescues him. Fearful of how the way Meyer folds him into his proximity by stories of him as a ‘good chap’, that Meyer accompanies by touching the narrator, if but by only a hand to the shoulder, will get turned into stories of ‘love-birds’, or worse, ‘bum-chums’ he looks to escape the feared consequences. As that story circulates and mutates it gets to the repressed and homophobic upper school, especially Rowntree, who ‘had an obsessive terror of anything vaguely homosexual. Who looked for it like a spaniel eating truffles’. It sounds like an accusation of everything Rowntree and institutionaised toxic masculinity fears. Rowntree asks the narrator if there ‘is any truth … in this story’ of the ‘two young, handsome lads’ who ‘were deeply in love, but something has torn them asunder’.[13] The narrator in responses, still a young boy, lets free Meyer’s private story told only to him to the latter’s humiliation and assumption of the role of the scapegoat boy to be bullied.

This story then is all about the possession and distribution precisely of stories – which of them, or parts of them, we allow to be known, and which not. Even in telling the story of Meyer’s attempted suicide’ later, of which he is NOT the only witness, he learns that there is a power dynamic involvement in the particular blend of ruth with lies and fictions that gets to be told in the interests of the powers that be and his ability to match himself with it or not. The story is brilliant in showing the social and ideological forces in masculine hierarchies which allow a lie to be transformed into an acceptable fiction and pass as truth,[14]

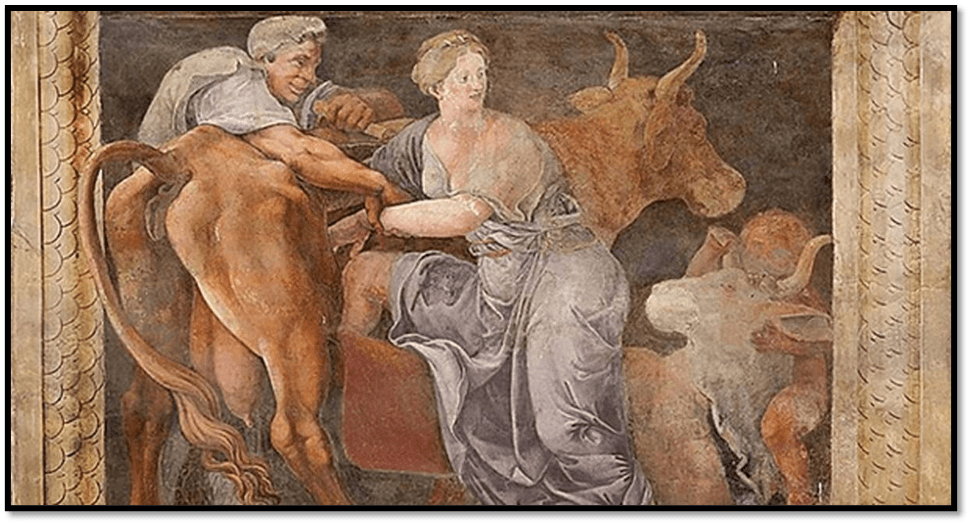

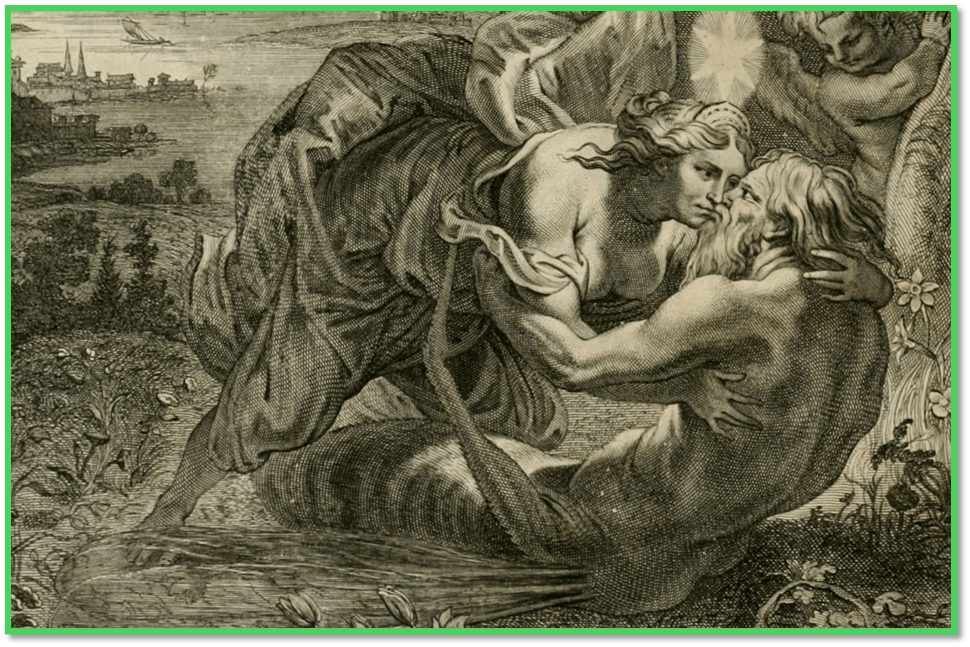

The stories in Dogs and Monsters were written an published over a long period but they contain echoes of each other. The old school has less obvious examples of dogs and monsters, though it has them, but it shares the feature I have discussed with the retelling, with vast shifts of time and space, some of which are clearly deeply anachronistic in effect – thus both Sir Philip Sydney and Montaigne are spoken of as contemporaries, and learned by heart by the female focus of the story’s hegemonic perspective. Based on the story of the Goddess, Pasiphaë , it concerns mainly the story of the incarceration of her son, supposedly sired by a bull to whom jealous Gods forced her to be enamoured, in a supposed labyrinth (which in truth is no such thing in Haddon’s version), and his escape to his mother’s continuing care (not a feature of the original where the son is a Minotaur – a bull from the house of King Minos of Crete – and the fearful monster he is said to be). There is no doubt that for Haddon, one less noble reason this story endures is the fascination of people with the means by which the queen of Minos manages to have viable sex with a bull.

I have taken my title to this blog from this aspect of the story. Minos introduces his queen to a ‘wily engineer’, based on Daedalus in the original, with his son, based on Icarus (although neither are given these names . The engineer is charged to invent the labyrinth to imprison the Queen’s son, called Paul in this version of the story. The Queen supposes that the knowledge of such am event is a story that, if let free to circulate with all of its truth intact, would endanger the life of the engineer and son. However, once charged the engineer engages – men of his court and army being asked by the king to leave on the engineer’s request to to tell another story on which the assumptions behind the story of the contents of the labyrinth will rest. The story is told as if factual and though the queen wonders whether her husband thought the ‘story might be true’, she only says the engineer is telling ‘detestable lies’ without ever directly challenging the story of her supposed sex with a bull. Given that no story he tells later is true – even those told to his son, whose death he seems to cause in ways that fit with the original myth, we seem justified in thinking that that this inventor is capable of only inventing dangerous fictions that cast slurs on others or cause them present danger and perhaps that cost them their liberty or life

The story of female sex with a bull (indeed the one from the myth) tells how a woman might be ‘pleasured’ by a bull if you build a cunning enough and well planned model of a cow that moulds human body parts hiding inside it with those of a real cow. It is a ‘vile’ story says Minos. The engineer at this point seems to admit that this is the whole point of the story and will endure its longevity as a response to deep fantasies listeners already have inside them either misogynistically against women or in some other dark area of wishful fantasy:

“Much depends on it being a story that people will listen to greedily and be desperate to pass on”.[15]

Any story that serves the purposes of the powers that be in any society, however anachronistic in its placing in space and time – Minos lives it seems somewhere from which Norwich might be accessible) and endures must be a story that people desire to hear over and over again. Such stories are like the stories of wanking and boys kissing whilst up trees and fucking other boy’s mothers that appeal in The Old School, or stories of living forever in The Quiet Limit of the World. Daedalus has always been treated as a symbol of the artist in iconographic traditions – this one is a popular storyteller, a Stephen King of Southern England, generating god and monsters from everyday human situations, like the birth of a child with physical characters, mental and intellectual traits that differ from the norm, as his nurse points out of Paul. This is, in fact, the theme of Haddon’s great debut novel, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, in which the autism of the narrator yields to fantastical stories of his specialness and / or his monstrosity.

The line between lies, truth, fact and fiction oft lies in the origin of belief in a person as a god or a monster, and sometimes, as in D.O.G.Z between dogs and Gods and humans. The Queen continually denies her son, Paul, is a monster or hybrid: ‘chimaera, part ape, part God alone knows what’. He is a ‘boy’, she asserts. He has ‘a name’, but, as Minos says: ‘We give names to dogs’.[16] Facts are nothing against desires and wish fulfilments, as the engineer’s Icarus-like son learns: ‘the imagined possibility of flight can make us blind to many ordinary and disappointing facts’.[17] Misery and darkness create imaginary beings too, as they do for Paul, who imagines he will be, as he as a Minotaur is said to do to others, be eaten ‘alive’.[18] The inconvenience he poses to his father and his sister make both of them reject relationship to him. His sister says: “He is not my brother. … The monster is not my brother”.[19] Yet people like to hear stories of their social superiors having sex with bulls, and of terrible retributions to criminals in a deep prison. As for the Queen, her life ends with all the people who tried to end her life being the subject of stories in which they, not her, are demeaned and ‘vanished’ politically. But still she says:

These are only stories. and I do not trust stories. … The truth is dull fare and we are dangerously enamoured of the extraordinary. These days if I read or hear some glittering tale and find my attention held fast, I ask myself, What suffering might these fabulous events conceal? Where am I being encouraged not to look? Who benefits if I am distracted and do not witness the mundane round of ordinary cruelty?[20]

The point is not only that myths serve ideologies of power and control – of those at the top of hierarchies over those beneath them, of men over women, of those labelled ‘sane’ and ‘normal’ over those dismissed as ‘mad’, deficient in learning ability, or even ‘bad’. It serves men over women but not consistently because of intersections of class, race and differing abilities and employers over employees, unless employees become smart like the engineer, and then even he …. And myths serve the hybridisation of the ‘human’ in ways that degrade it. It is why some men call some women ‘dogs’, but even the Queen, a mother in pain when her son is ‘disappeared’ wonders whether the fact that cannot ‘rest’ means she is like ‘a grieving bitch whose puppies have been taken away in a bag and drowned and can do nothing but prowl and keen’.[21] Now to use the dog as a similar is not necessarily reductive – it emphasises the true feeling of mothers of the ‘disappeared’ anywhere – IN South America, Gaza, at any point in history or even in Norwich. Is it inhuman to be like a bitch or is it inhuman to be the monster who condemns mothers to the loss of her children for political ends. The same point emerges in the story Wilderness, where the trapped subjects of cruel experiments – neither clearly women or dogs or something superior to everything say to a woman who comes into the facility that cages them, or has done so: ”Who the fuck are you? … Bitch,, I’m talking to you…./ / “ Bitch.” The woman clicks her fingers. “Look at me. You one of them or one of us?”[22] The ideas are similar to this story’s inspiration, H.G. Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau.

The language we use has a lot to answer but so does the physical treatment of a person like an animal, or a monster or even like a God. It metamorphoses the person. It is better in the end that Paul does not learn language and the false distinctions it embraces.[23] But the Queen in The Mother’s Story has a point that no social worker should ever NOT HAVE LEARNED that of a person they try to engage but fail because of a history of bad treatment:

I still dot know if there was anything wrong with (Paul). I believe it is entirely possible that all the wildness and the damage were the results of his being treated like an animal and that the healthiest of children would have fared no better if they were tortured in a similar manner.[24]

This is a wondrous collection. One of my favourites in it is The Quiet Limit of The World. It retells the story of Tithonus, taking not only from Sappho but Tennyson and coming out with something entirely different. I get the feeling Nina Allen thinks it one of the ‘more meandering’ stories raised like the rest by the ‘quality of the writing’. That latter point is true but meandering is all a story can do if it is about someone that can never die, never be complete and never ended. Read it like this and it is a miracle even the fantastical metamorphosis at the end. But it too is a story about testing the limits of the human, against both the divine Gods and animals, and, of course, dogs. It is wonderful because it starts off as a novel about heterosexual male narcissism and ends as a story about queer compatibility and realism about what endures in any relationship if it cannot change.

As a result its embrace of queerness is neither heteronormative or homonormative, it is a matter of the pragmatism of the negotiations between persons who learn to trust something in each other or not that cannot change. ‘He takes other lovers. Men, mostly’, because of the complication of social expectation of both heterosexual loyalty whatever the event and the fact of children he MUST abandon.[25] The description of a beginning male-to-male love between Tithonus and Hannikar tryst that does not last but endures in memory is one of the most beautiful I know.[26] And more importantly the story attempts to put a case for laying the myth of quantitative experience of time as a path to wisdom and correct choices in relationships or ask or achievements. What he realises is that ‘reality’ differs for the conditions in which one lives – whether of accommodation, wealth, the range of different knowledge in different cultures and languages. Yet these ‘experiences’ have not ‘given him a better grip on the slippery reins of life’. They still slip from his grasp.

And more than that it takes him to be old and not dying, for that he cannot do, to finally see the real ‘old and dying in the world. How had he been so blind to them before’.[27] I thin the issue is that we choose not to see vulnerability until we share some part of its vulnerability or entitlement, and one we see it we see little else. All he in fact learns as a generalisation is about the awful truth of how a ‘them’ and an ‘us’ in all situations that is fuelled by the stories hey tell of each other, whilst never seeing each other at all:

More and more he thinks there is a deep need for people to believe that we are chosen and they are damned.[28]

There are others amongst these 8 stories that I have not even touched upon. But they are superb, even if not exhausted, not at all, if only read once. The demand a further repetition, for you will find it is not repetition at all, but new discovery.. Do read this.

With all my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Mark Haddon (2024: 7) Dogs and Monsters London, Chatto & Windus.

[2] Ibid: 202

[3] Ibid: 133

[4] Ibid: 134f.

[5] Ibid: 131

[6] Ibid: 132

[7] Ibid: 134

[8] Ibid: 139

[9] Nina Allen (2024: 50) ‘Brilliant beasts: Greek myths inspire a master storyteller’ in The Guardian Supplement (Saturday, 31st August 2024), 50.

[10] Ibid: c.85

[11] Ibid: 79

[12] See ibid: 84 & 89 respectively.

[13] Ibid: 93 – 94

[14] Ibid: 106f.

[15] ibid: 7

[16] Ibid: 8f.

[17] Ibid: 25

[18] Ibid: 22, 46 respectively.

[19] Ibid: 35

[20] Ibid: 54f.

[21] Ibid: 16

[22] Ibid: 157

[23] Ibid: 28

[24] Ibid: 10

[25] Ibid: 236

[26] ibid: 235

[27] Ibid: 242

[28] Ibid: 244

One thought on ““Much depends on it being a story that people will listen to greedily and be desperate to pass on”. This is a blog on Mark Haddon’s ‘Dogs and Monsters’ (2024). ”