The internet is full of quasi-psychology that is, whilst sometimes pretending to be folklore, about ‘being yourself, with a plethora of websites offering tips about how to be yourself. These tips rarely extend beyond recommended changes of behaviour or attitude to ‘self’, although they often include that time hallowed impossible injunction to ‘know yourself’. This Google AI summary of its researches will serve to typify these, most being highly dependent on the advice of humanist psychology since Carl Rogers.

To “just be yourself” is to live authentically by aligning actions with personal values, embracing uniqueness, and letting go of the need for external approval. Key steps include practicing self-compassion, setting firm boundaries, and identifying personal, core values, which helps reduce anxiety and attracts genuine connections.

The whole reminds me of Carl Rogers ‘encounter groups’ where participants would learn to advise each other, often harshly, to drop the ‘masks‘ they used in the world outside of the groups based on some role’ social or idealised. And stay there long enough and authorities arrested brought into the argument. Then first is usually the maximum attributed to those at Delphi in the Temple of Apollo:

‘Know thyself” (Greek: Γνῶθι σεαυτόν, gnōthi seauton)[a] is a philosophical Delphic maxim which was inscribed upon the Temple of Apollo in the ancient Greek precinct of Delphi.

Yet the history of that phrase reflects changes in expectation of what humankind is, as opposed to the Gods, rather than to some search to match unique inner being to what shows on the outside. The second is the seriousbit from the advice of Polonius to his son Laertes on the latter’s departure to Paris to improve himself:

This above all: to thine own self be true,

And it must follow, as the night the day,

Thou canst not then be false to any man.

But profession of understanding this advice often slides the difficulties of its practical application to human life. To be true to yourself in modernity often implies the advice of the encounter groups – don’t wear a mask over your true face. But it equally follows from the context that it is about the manner in which we witness truth in social interactions, avoiding being ‘false’ to others in deeds and/or words ptecisely because we are ‘true’ to ourselves in deeds and/or words. And consider that word ‘follows,’ as a profession of logical congruence.

Polonius makes nonsense of it because night only ‘follows’ day as a matter of sequence not of logic. And that is because Poliniuz as usual is talking nonsense. Because you tell truths to yourself about yourself does not mean you cannot tell lies to others cannot or act in a way that substantiated lies in the eyes of another. If that were not true thee would be no case for distinguishing appearance from reality, or what seems to be true and what is true.

And hence we get a play in Hamlet, that proposes in the words of its hero that it is only possible ‘To be or not to be’, for being is a question of ontological existence not of the reliability or validity of the image someone creates of themselves in appearance of look, act, or word. The play even puts that idea centre stage – in constantly worrying about you enact or perform another being as in the play-within-a-play sections, or in this rough exchange of Hamlet with the person he thinks has become ‘false’ to her role of his mother:

QUEEN

Good Hamlet, cast thy nighted color off,

And let thine eye look like a friend on Denmark.

Do not forever with thy vailèd lids

Seek for thy noble father in the dust.

Thou know’st ’tis common; all that lives must die,

Passing through nature to eternity.

HAMLET

Ay, madam, it is common.

QUEEN If it be,

Why seems it so particular with thee?

HAMLET

“Seems,” madam? Nay, it is. I know not “seems.”

’Tis not alone my inky cloak, good mother,

Nor customary suits of solemn black,

Nor windy suspiration of forced breath,

No, nor the fruitful river in the eye,

Nor the dejected havior of the visage,

Together with all forms, moods, shapes of grief,

That can denote me truly. These indeed “seem,”

For they are actions that a man might play;

But I have that within which passes show,

Queen Gertrude does herself no favours by accusing Hamlet of creating an image of sorrow rather than feeling a sorrow that exists, that is, really is, inside him. Sorrow is not just a ‘nighted colour’ nor can you change your mood merely by changing what your gaze or look ‘looks like’. If only those tedious cognitive- behavioural counsellors read this play more often, they might see their model in this.

Hamlet insists that that which he feels within ‘is’ or has being, it doesn’t just ‘seem’to be like something it may or may not be. Therein lies the problem of ‘being yourself’ for, at some level, it is a performance to others, for knowing what is truly inside you can ot be a matter of external judgement, however skilled the observer. Gertrude and Claudius have a point. However much one protests to be ‘being yourzelf’ to an observer it must always be an performance of that self, whether a good or bad one (wherein being good means it more effectively convinces others of its authenticity).

But consider now what it means to want to ‘be’ someone else for a limited time. The best expression of what it might mean to be someone else is put into the mouth of Catherine Earnshaw by Emily Bronte in Chapter IX of Wuthering Heights.

… I cannot express it; but surely you and everybody have a notion that there is or should be an existence of yours beyond you. What were the use of my creation, if I were entirely contained here? My great miseries in this world have been Heathcliff’s miseries, and I watched and felt each from the beginning: my great thought in living is himself. If all else perished, and HE remained, I should still continue to be; and if all else remained, and he were annihilated, the universe would turn to a mighty stranger: I should not seem a part of it. – My love for Linton is like the foliage in the woods: time will change it, I’m well aware, as winter changes the trees. My love for Heathcliff resembles the eternal rocks beneath: a source of little visible delight, but necessary. Nelly, I AM Heathcliff! He’s always, always in my mind: not as a pleasure, any more than I am always a pleasure to myself, but as my own being. …

Catherine is a philosopher, ‘being’ is meaningless and mere performance unless represented in some greater essence, such as an idea or ‘form’ of yourself in the mind of God; ‘an existence of yours beyond you’. She does not fill out the idea but it is clear that Catherine thinks that ‘herself’ in a world that was the other than in the absence of Heathcliff, an absence akin to the ‘annihilation’ [making nothing (a non-being) out of something (that once had being)] would mean that ‘the universe would turn to a mighty stranger: I should not seem a part of it’. But for Catherine to think this she must see Heathcliff as representation of something durable underlying the appearances of space and time. She would never ‘desire to be Heathcliff for a day’ for that would be the equivalent of making Heathcliff a transferable quality with no essence, not something beyond the capacity of time to change or equivalent to that which underlies the appearances of the earth. Being Heathcliff for a day is as impossible as world that had so little solidity underneath it that space and time collapsed into a black hole.

Without Heathcliff Catherine herself becomes someone, whom she says in a dream of the solicitor who ‘has been a waif for twenty years’ as she holds onto this shallow man for reassurance she will never get – indeed instead of reassurance he grates her arms on a broken window so that it bleeds, or so it seems to him in his lurid dream of resisting possession by a ghost. The world of the Victorians was as fascinated by the existence of waifs as it was resistant to amend the conditions that produced those alienated entirely by society into conditions of poverty and absolute self-reliance, even that which a life of criminal otherness alone allowed them to find, though Dickens did his level best to make their existence known in his novels. Catherine excluded from everything which could offer a ‘home’ and ‘being’ to her is something whose existence is doubted by all at this point of the novel but Heathcliff, although still incapable of giving her valid and reliable evidence of ‘being’ other than as something lost and gone forever.

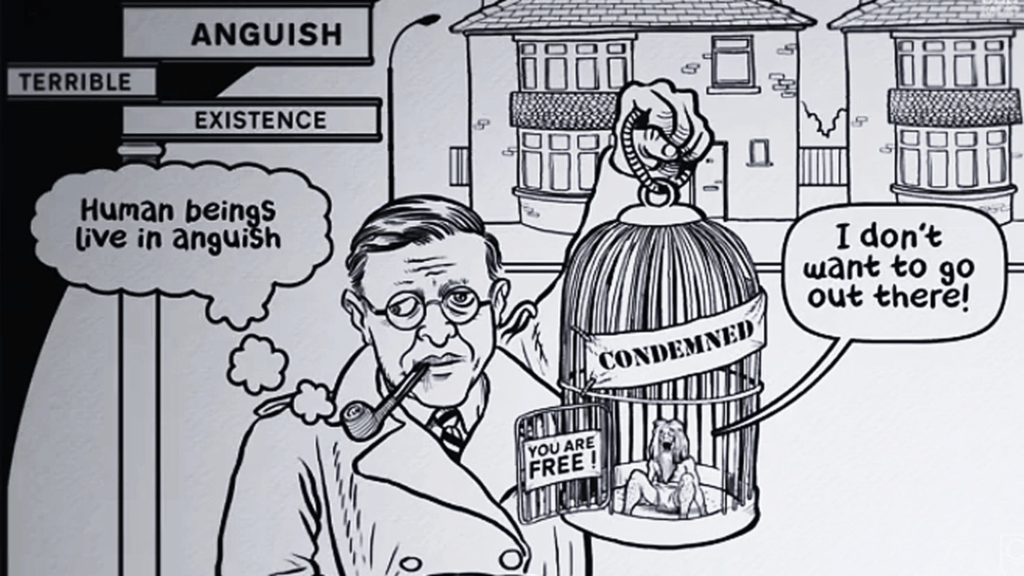

Let’s say that the obvious impossibility of being someone else is, in a world where space and time dominate and the enduring impossible, the real reason that no-one can ever be themselves either, for that self they are told to be is no less an image or appearance of the world that suits its current circumstances – it changes as it must change: the real meaning of Heraclitus’ proposition that ‘you can’t step in the same river twice’, for by the second time both you and the the river have flowed on. The existential reality as Sartre and Camus knew is that you can only make anguished decisions that authenticate you for the time and place in which you make them and in that seek being, rather than the nothingness of doing as you are told, even by yourself – or your father – even when those voices tell you to ‘know yourself’ and ‘to thine own self be true’.

All for now

With love Steven xxxxxxxxx