The Radio Times tracked down the designer of the shoes made specifically for J.K Rowing and shown above as Sophia Webster. If you had to design shoes for J.K. Rowling then why not base them on the golden snitch, a quidditich game ball which sounds, at least, a thoroughly gendered item with no non-binary aspect at all – although they would grace any drag act. They are designed to hide and reward only those who look for you. And when such shoes were required for the red carpet of a first night, Rowling clearly required that these be high heels, in which a womanly foot can be most distorted to prove itself the real womanly thing. Rowling herself was interviewed by the unlikely online magazine High Heels Daily, and said:

I have often wondered in a vague way why women are so obsessed with this particular item of clothing. And I think it is undeniable that probably shoes do come first in the most mythologised, fetishised item list.[1]

There is something of the weird about that quotation for someone who in other contexts makes a virtue of giving simple answers to ‘what a woman is’, if asked as a question. Read the entire interview (at this link) just to realise how obsessed the writer is with binary sex/gender. Above she has no doubt that there is something basic about female desire for the appearance lent by shoes and that, though she sees them as matters of mythology and fetishism, is quite happy to endorse that these myths and fetishes do complement the essence of ‘woman’ Hear, after all, a story proferred by Rowling without invitation by the interviewer of ‘a friend’ who once met a male ‘high heel shoe’ fetishist: .

I think there is clearly a dodgy subset of men who really do care about women’s shoes. I’ve never met one of those. Although a girlfriend of mine did once – I don’t know whether this is true or not – she swore to me that she’d met a man and all he wanted to do was buy her stilettos. It sounded like a fantasy to me but apparently there are such men out there.[1]

I find that quite unpleasant in its snide suggestions about ‘such men’ in order to insist that this is an exception that proves a rule that women are the only sex with such a legitimate obsession with this manipulation of appearance, gait and pressure on body size and balance. Asked about herself, she said:

I love a heel. I’m short, I’m only 5 foot 4 and a half [inches]. People are often surprised at how short I am because I wear heels so often. So people assume I’m a nice willowy 5′ 9″, but that just shows you what high shoes I wear. [1]

There is a kind of obsession with appearance adding a kind of magical transformation to the look of a woman, that Rowling clearly believes to be rightly ‘womanly’. Is this, I wondered to myself that the key guru of fetishised binary sex categories believes that women prove themselves as being biological what they are by magical changes of appearance – except that the magic is about little else than a very arduous training in a balanced stance and gait in high heels – which only a ‘dodgy subset’ of men mimic. As far as I am concerned this appearance of thought about sex/gender is much the same pure nonsense attributable to Rowling in lots of her increasingly unhinged social media and that of her even more unhinged X supporters, including some men.

There is a analogue in the history of male thought, which lies in George Cruikshank’s retelling of Perrault’s fairy story of Hop o’ My Thumb and the Seven-League boots. Cruikshank’s illustration of Hop visiting the King with his Seven league Boots, stolen from an Ogre who used them for evil purposes, makes it quite clear that Hop is obsessed with the shoes that take him places, although he decides where, as an aspect of their appearance. Below the drawing is an extract from it, all from the Victorian Web webpage (at this link). Whereas Perrault sees Hop as a practical youngster of small stature who takes the boots as a means of using them to get in the employ of the King and earn a wage beyond his greatest desires (magical thinking of course but how practical), as you see below:

As soon as ever Hop-o’-my-Thumb had made sure of the Ogre’s seven-league boots, he went at once to the palace, and offered his services to carry orders from the King to his army, which was a great way off, and to bring back the quickest accounts of the battle they were just at that time fighting with the enemy. In short, he thought he could be of more use to the King than all his mail-coaches, and so should make his fortune in this manner. (cited [2])

Cruikshank shows Hop instead showing off his boots, not least their magical capacity (that is in Perrault) to change size to fit their current wearer, so that he and the boots, the latter’s majesty of size (much taller than the entire height of Hop, reflecting back on him, impress the King by their appearance (so much so that in Cruikshank, and not in Perrault, the King wants to buy them, as if Hop were a giant in the new science of advertising.

This is how Cruikshank glosses the event in prose:

Well, when he arrived at the palace, he came into the courtyard at once, to the astonishment of all the officers and soldiers in the place; and he demanded, as loudly as he could, to be led into the presence of the King without delay, as he had an important communication to make to his Majesty. Accordingly, he was led to the audience-chamber, where the King and Queen were seated upon a throne, and a young Prince by their side. The chamberlain laving announced this extraordinary visitor, introduced him to the King and Queen, who were much surprised and amused at seeing such a tiny little gentleman. He made a fine bow, and informed his Majesty about the Giant-Ogre, and also described the wonderful Boots, which he took off and placed before the throne. The Boots, which were, of course, so very small when he had them on, when off they expanded themselves into a pair of good-sized Boots, and they then made most polite bows to the King and Queen, and also to the young Prince. The King at once saw the importance of possessing such invaluable Boots, and determining to buy them of the little fellow, inquired his name. (cited [2])

What a difference. Hop does not delight in the magical transformation to use the magic to up his economic and social status, but rather delights in making a thing of that appearance of which he has control, as if it were his ‘capital’, capable of producing added value and profit to himself, much of which is entirely performative in nature, with fine bows from him and ‘polite’ ones from the Boots, for they don’t upstage their diminutive new Master. In Cruikshank the event is all about appearance. Unsurprisingly Cruikshank makes it predictive of the workings of High Capitalism in his own age, as said in the Victorian Web commentary:

Hop becomes the a corporate “Director” of Telegraphs, and counsels the King to conquer the giants and ogres, and then, instead of executing them, deploying their enormous strength to useful purposes, “and employed them, under guards, at different places where great national works and improvements were required, — such as new roads, draining marshes, and making harbours ofd refuge and security for ships” (29). The political model is not the mediaeval “kingdom,” but the modern “nation.” In spite of the traditional scene at court that concludes the visual program of the fairy tale, this is no longer a backward country beset (as at the beginning of the story) by privation and food shortages, but an advanced European country. And, unlike the nemesis of the traditional fairy-tale, the hero does not marry a princess or slay the antagonist; Hop does, however, act as catalyst for highly beneficial social change, and does restore the family fortunes. [2]

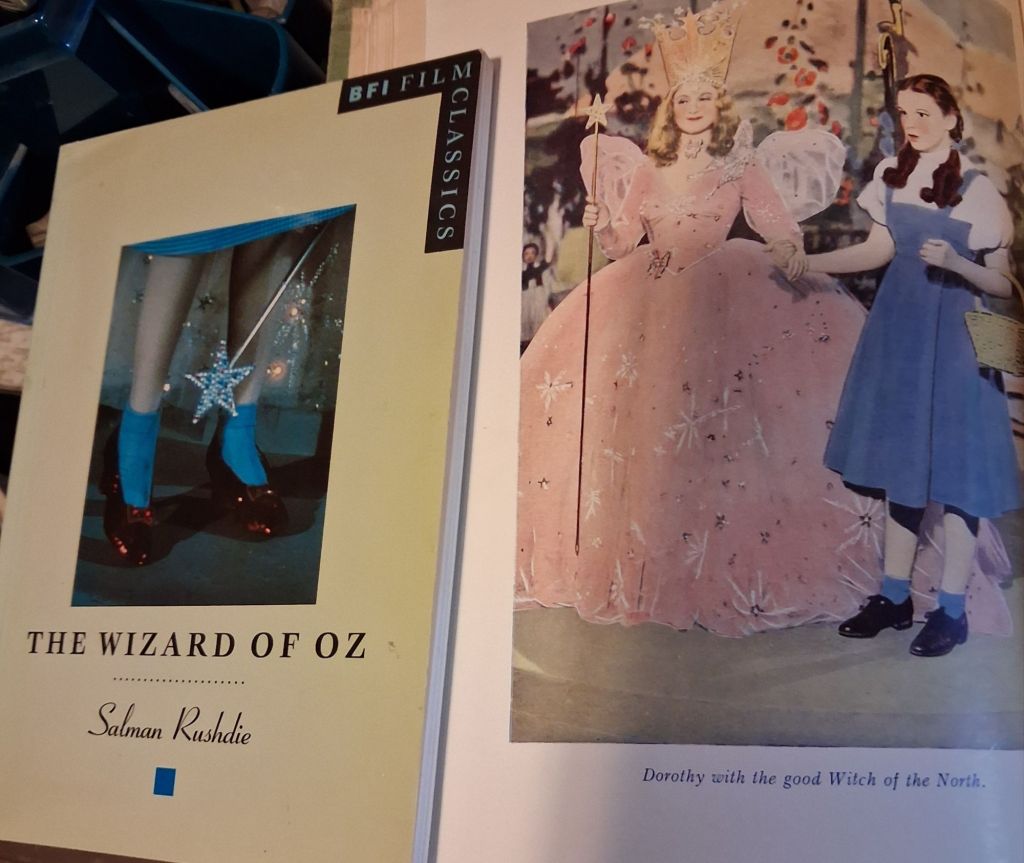

This analogue is as useful an interpretation of Rowling’s magical thinking about women and shoes: it is all about appearance. This is what fascinated Salman Rushdie about a key feature of the famous musical film The Wizard of Oz in his fine BFI monograph on it. Everybody talks of the magic of the Ruby Slippers (the film added these) but no-one ever defines it until, weirdly, Dorothy learns it herself : she was always better off at home! The unspoken lesson being being that, women can glow on nights out in the right pair of shoes. Rushdies says that everything said about the ‘magic’ of the slippers is contradictory and that ‘these confusions are hangovers from the long dissension-riddled scripting process, in which the function of the slippers was the subject of considerable dispute’. [3] He neglects to say here what he implies in covering the later auction of the shoes that the meaning of these shoes is in the appearance of ‘womanhood’ (and all the terrible diminishing and sexualising effects that had on intelligent girls) in the girl Dorothy as if the result of a magical transformation – powerful enough to find a very sexualised and oppressed Judy Garland hidden in a dowdy Kansas farm-girl, who would be better off sticking with her school books and a ticket out of Kansas.

Rowling is another version of this mock-feminine ‘magical thinking’, whose purpose was once to maintain the binary sex’gender division in a way not unlike the commodity fetishism in Cruikshank’s seven-league boots, no longer making a big man out of a small one but making an appearance. A bit like the celebrity of the awful writing of J.K. Rowling. Thank goodness every friend of Dorothy wants their own ruby slippers to fight back. I dedicate that to Mike.

Available at: https://quotesgram.com/img/ruby-slippers-quotes/13956437/

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

____________________________

[2] See https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/cruikshank/fairy7.html

[3] Salman Rushdie (1992: 43) The Wizard of Oz: BFI Film Classics London, BFI.