It is an ancient theme, as ancient as the first epics of war between tribes and peoples that certainly precede Homer but refined by the Romans into a dream of men as made of steel, flexed into active form by fire. Hence though Homer’s The Iliad mourns war in telling of it, Vergil’s The Aeneid only does so in the interests of its glorious continuation. My title quotation – which in context, translates as by which HE (Mars – the God of War) men, by which cities he stirs into action’. The context is a description of the forge of Vulcan, worked by monstrous beings to create armour – in our quote the wheels of Mars’ winged chariot are being forged to stir up men – the means of stirring up cities, otherwise peaceable. Here is the full description from The Aeneid, Book 8, lines 416 ff. (translation in footnote).

insula Sicanium iuxta latus Aeoliamque

erigitur Liparen fumantibus ardua saxis,

quam subter specus et Cyclopum exesa caminis

antra Aetnaea tonant, validique incudibus ictus

auditi referunt gemitus, striduntque cavernis

stricturae Chalybum et fornacibus ignis anhelat,

Volcani domus et Volcania nomine tellus.

huc tunc ignipotens caelo descendit ab alto.

ferrum exercebant vasto Cyclopes in antro,

Brontesque Steropesque et nudus membra Pyragmon.

his informatum manibus iam parte polita

fulmen erat, toto genitor quae plurima caelo

deicit in terras, pars imperfecta manebat.

tris imbris torti radios, tris nubis aquosae

addiderant, rutuli tris ignis et alitis Austri.

fulgores nunc terrificos sonitumque metumque

miscebant operi flammisque sequacibus iras.

parte alia Marti currumque rotasque volucris

instabant, quibus ille viros, quibus excitat urbes;

aegidaque horriferam, turbatae Palladis arma,

certatim squamis serpentum auroque polibant

conexosque anguis ipsamque in pectore divae

Gorgona desecto vertentem lumina collo. [1]

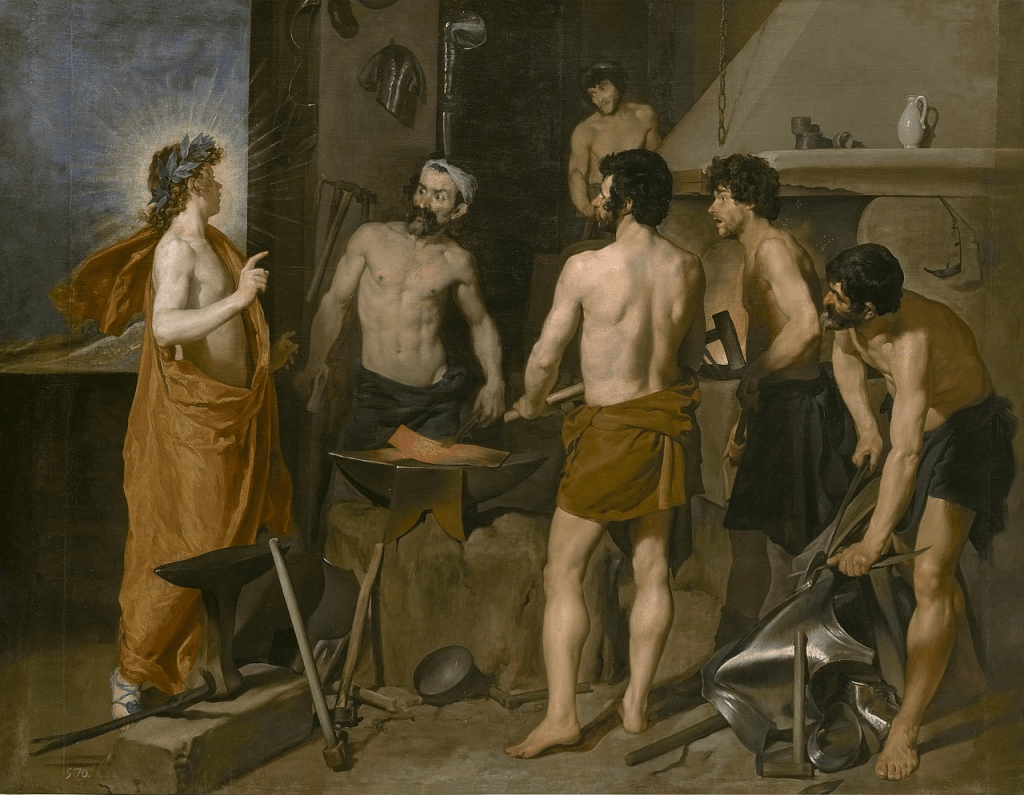

Though it is an ancient theme, in modern times Eduardo Paolozzi saw Vulcan not just as a big God from above visiting his subterranean forge at Etna to get his monster ‘Cyclops, Brontes, and Steropes, and Pyragmon, the latter with naked limbs’, working hard but a worker himself. This was not the first time an artist had differentiated the god from the worker. Velasquez shows the god Apollo ordering the shield: Vulcan being merely one of the team at work, making his preference for the visual beauty of the strength of working men’s torso’s over the washed out mere boyishness of his Apollo.

Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan (Spanish: Apolo en la Fragua de Vulcano), sometimes referred to as Vulcan’s Forge, is an oil painting by Diego de Velázquez completed after his first visit to Italy in 1629. Critics agree that the work should be dated to 1630.(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apollo_in_the_Forge_of_Vulcan)

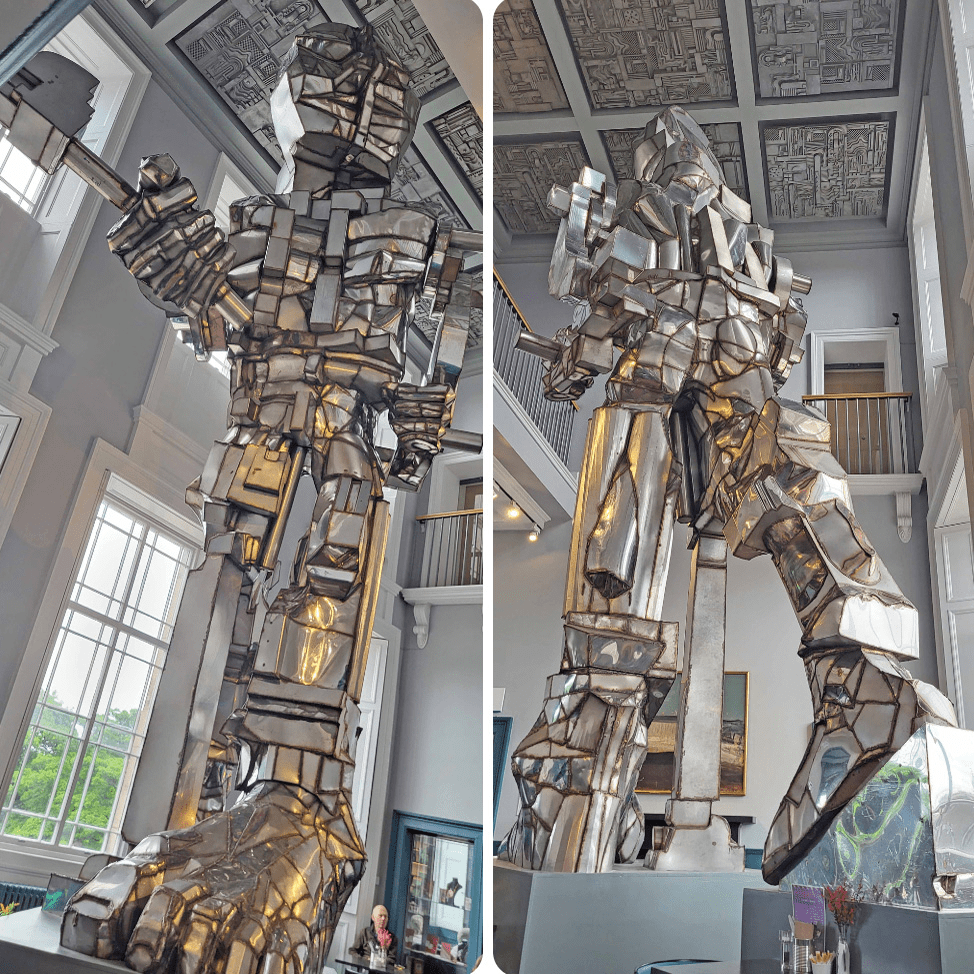

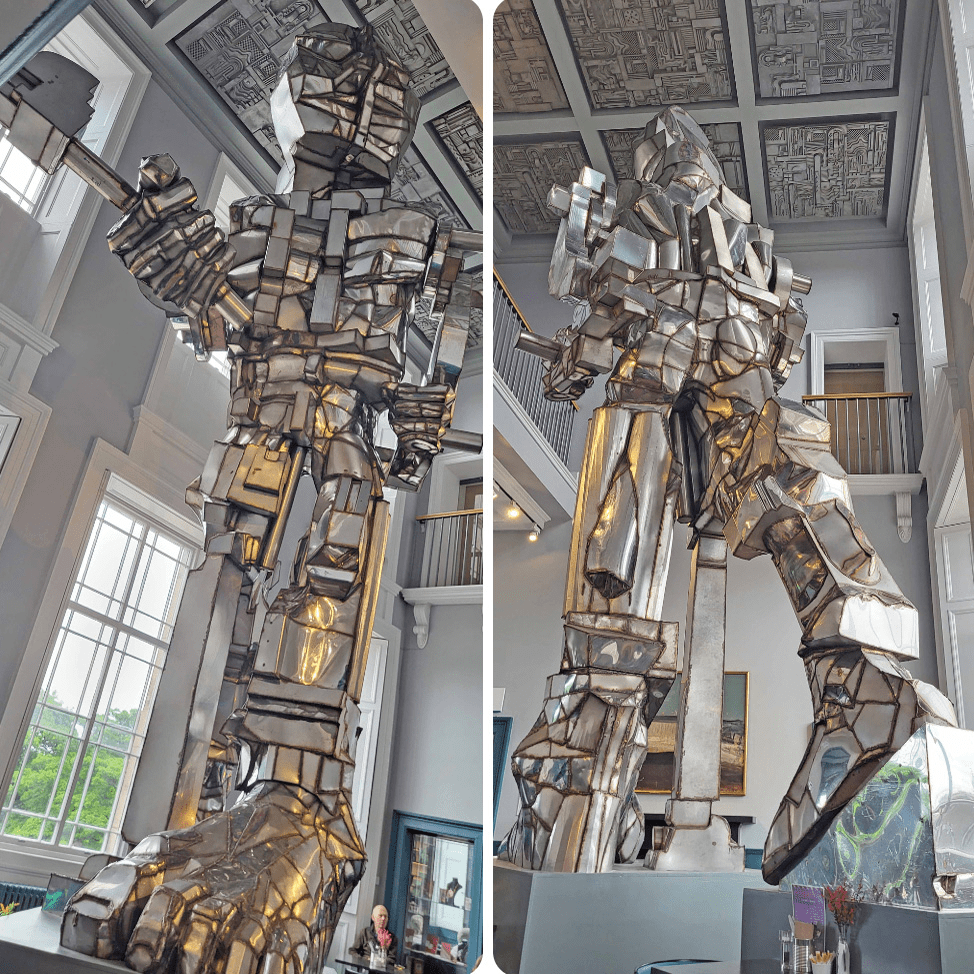

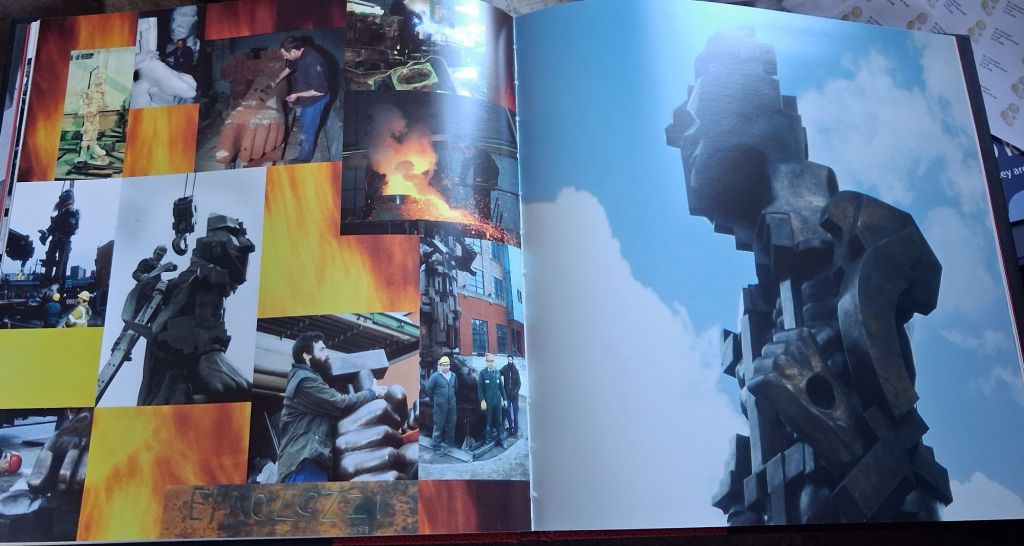

Paolozzi’s Vulcan is huge and he has a constructive purpose on which he is intent, is a kind of icon of the idea of the combination of fleshy practical but not very beautiful body parts like those huge stabilising feet, naked human limbs and industrial machinery that belonged to an ideal of the human construction of the world as a ‘machine for living in’, Le Corbusier‘s definition of a home. The version of him in the The Scottish Modern Art Gallery (One) is impressive but overly contained – physically and conceptually in a Tennysonian Palace of Art (and artificial light),

He lacks the feel of what drives him. There is another version in Central Square, Newcastle upon Tyne, that braves the external elements, sometimes of light, often of gloom. Its body members that are most like human flesh member – its hands and feet (the symbol of the parts of the worker that get things done, assisted by the flexion in the rest of the body feel more human, less robotic than the panel formed ones in Edinburgh. The Newcastle face is less robotic, though a fleshly face in pain with its mouth, as it seems, barred from opening and independent speech.

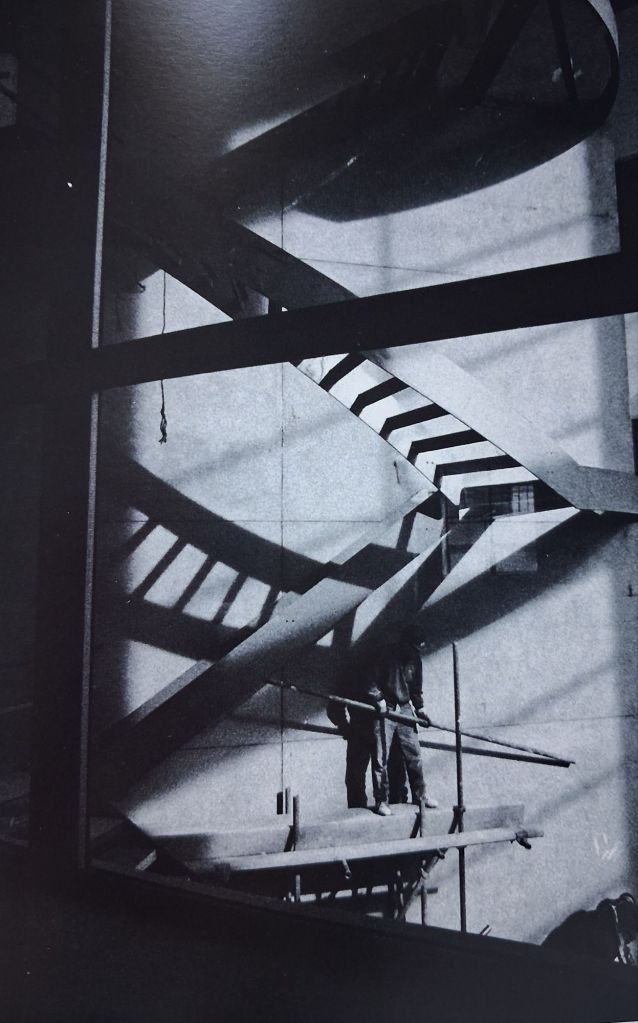

I didn’t know this piece existed till Geoff bought me from Oxfam a rather intriguing book called Squaring the Circle about the construction of Central Square and South Central Square by Parabola Estates Limited, who commissioned this book with text by William Varley and superb photographs by Keith Paisley. The photographs make this book special, though some are merely functionally good, like that above, as representations, others are works of art in themselves where construction of huge constructions out of vast parts and machine-aided manipulations thereof become most beautiful – something Paolozzi does not quite see in his Vulcan. Mt favourite is that re-photographed from the book below, in which, seen through the grids of an unyet finished tiled-glass (before the glass is fitted) window pane, a male form (head and shoulders obscured by a mix of hanging and unfinished internal built supports and the shadows of them cast from above (even here Apollo as the sun is present) precariously working on a high platform is dwarfed by huge structures of reinforced concrete and shadows yet again. It is difficult to divorce structure from its shadow – that being almost a definition of art in my mind. It is beautiful but partly because of the precarity of the man’s position in it, as if deserted by his Vulcan scaffolding and standing high above dangerous depths that machines straddle more easily.

Another photograph shows that machines can destroy (in demolition work) more effectively than the man it swallows into its transparent innards to mimic what his hand would do had it the size and energy of this crane’s grasping, tearing hand. Yet that man, with his arms and hands held out like the figure of Frankenstein in robotic movement as he controls the cranearm with levers, also feels like an amalgam of vulnerabilty with vast, almost incomprehensible strength, except if analysed from the physics of the movable parts of the dynamic engines that have swallowed him.

Neither man however seems intent on war. Neither, let it be said so Velasquez’s iron-smiths, seem thus intent. I suppose a ‘marxising’ socialist like me might see them, as stereotypes of such types suggest, as the victims of capitalism – fed into its endless cycles based on cycles of production and consumption, productivity and waste – but that is a very unnuanced position, even given that text and photography are made at the behest of capitalist financial institutions who feed off the cycle of real estate renewal.

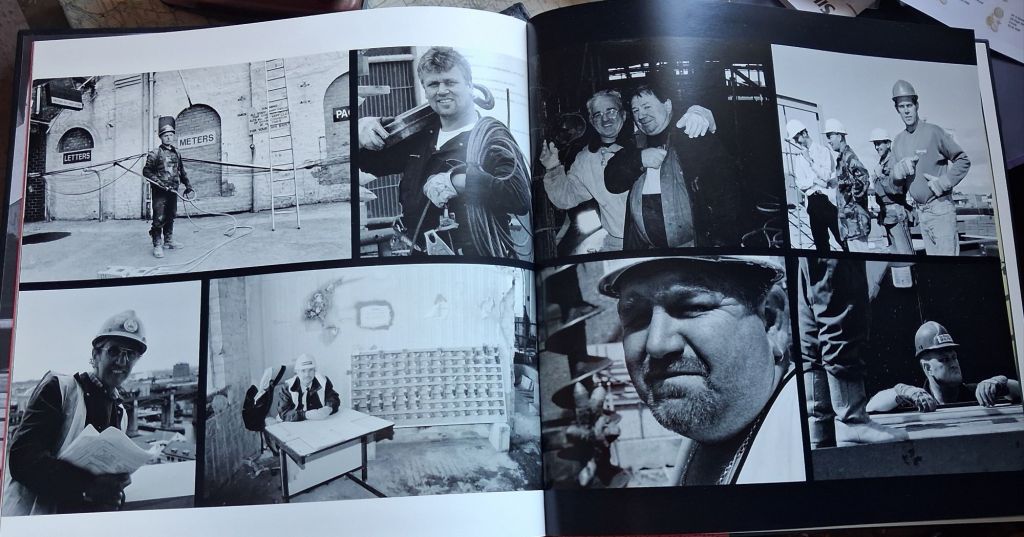

This book also celebrates me – not as figures of attraction or beauty, though not the opposite of that either – but of work.Even in their absence from work, their work is implied. Where below we see a beautiful combination of interior construction laid open to shadows cast by the external sun in the morning before work starts, men are present in the scaffold, a ladders awaiting one on the first floor. There is a figure at the portal on the ground floor. He is diminished by that into which he enters but, with his comrades will soon dominate it. Note that i have used the term ‘men’ throughout, for even though published in 2002, this bookcontains not a single female construction worker to feminise what is vulcanised. I can’t defend this but I can’t condemn either the fact that its aim seems throughout, as in Velasquez, to raise the praise of men.

The text , in dealing with the early construction in 1999 sings of them thus of the Geordie lads (even comparing them to a Geordie iconic TV show first broadcast in 1983-4):

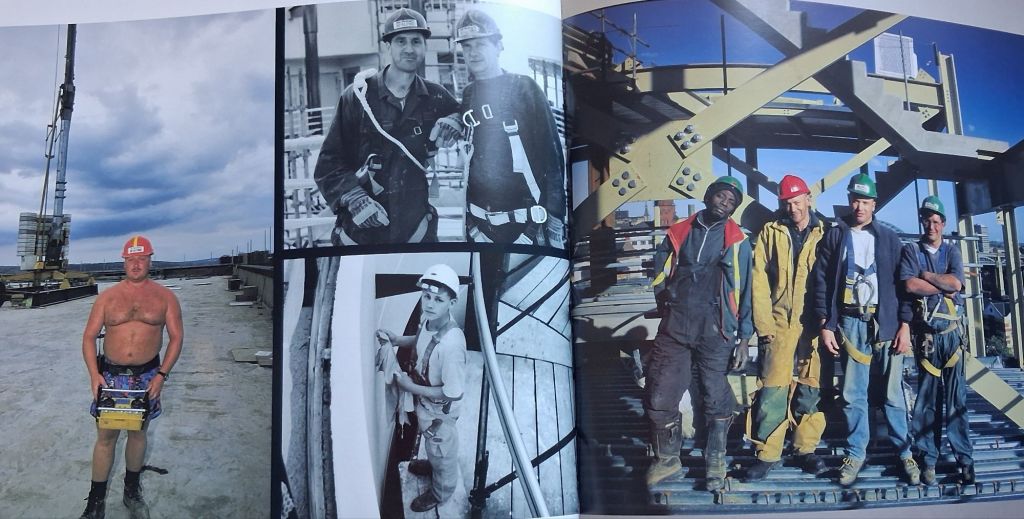

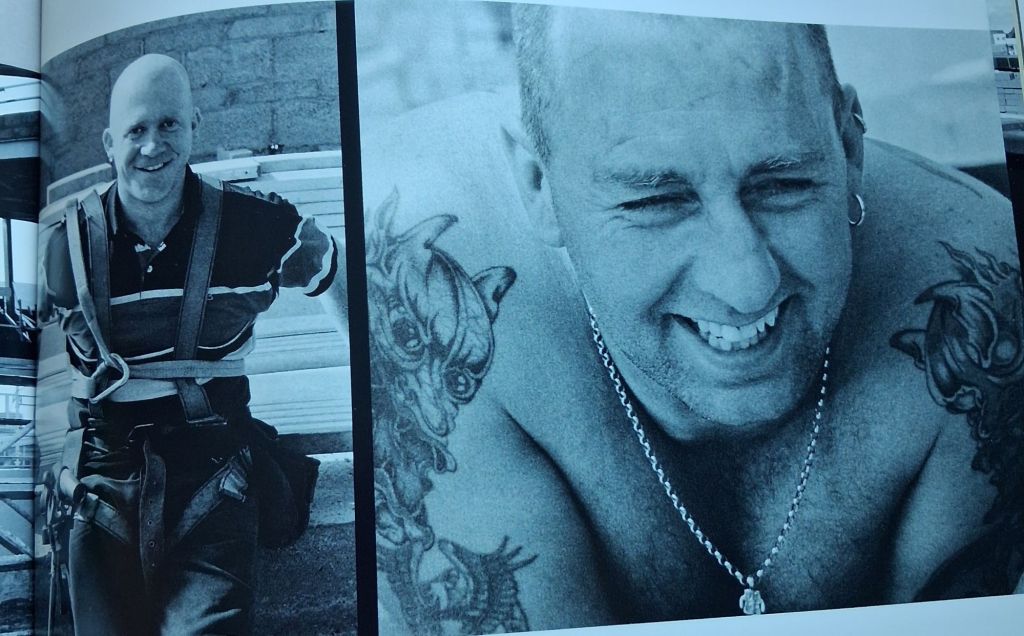

… a group of larger-than-life characters every bit as memorable of those of Auf Wiedershein Pet, were making their presence felt. There was, for instance, Jimmy the hod carrier, who was forever taking his shirt off for the camera, leading some to compare him with Ravanelli and others to the Full Monty. Their nicknames too could easily have come from Damon Runyan’s New York stories, ‘Gripper’ the pile foreman, for instnce., or ‘johnny the Horse’, (a betting man, naturally). Visually they were pretty distinctive too: gary the steel erector not only sported dragon tattoos, but made a convincing AndréAgassi look-alike.

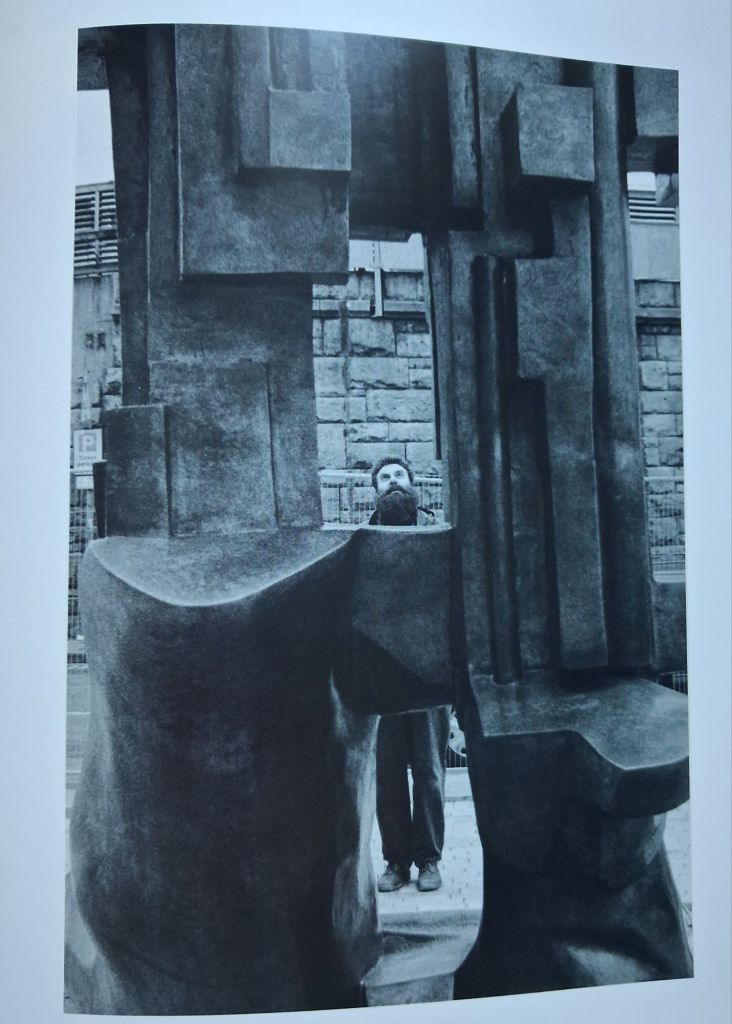

I would have preferred, though the Geordie lads might not, less reference to celebrity, for the photographs have a nobility and human freshness and lightness that celebrities lack. But one celebrity graises these pages – Vulcan himself, the sculptor Paolozzui, below staring through the legs of his alter-ego Vulcan.

And the below showing how cooperative a ‘work of men’ was Vulcan in full colour, with the artist himself carrying about some heavy stacks of his pre-creation

It is a lovely book – my Valentine’s Day present from hubby! That excites me – not war which ‘bores me’ , because people praise in it the killing of every beauty we possess for the interests usually of the few who invite it.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

_____________________________________

[1] Source: https://www.pantheonpoets.com/poems/vulcans-forge/

Between the Sicilian coast and Aeolian Lipare

towers an island of smoking rocks, under which

a cavern and chambers hollowed by the forges

of the Cylopes resound, the boom of mighty blows

on anvils echoes back with the hiss of smelting

iron and the fire roars in the furnaces. It is

Vulcan’s home, Volcania is the island’s name,

and the fire-Lord stooped to it from high heaven.

Cyclopes were working iron in the vast cave, Brontes

and Steropes, and Pyragmon, naked as he worked.

They had in hand, part done, part unfinished, one

of the many thunderbolts that the Father hurls

to earth from all over the heavens. They had put in

three rings of pelting hail, three of soaking cloud,

and three each of ruddy fire and racing South-wind.

Now they were adding fearful flashes and crashes,

and wrath backed up with blazing fire. Elsewhere

they were building Mars a chariot on swift wheels,

such as he uses to rouse up men and cities;

and working hard to adorn the panic-breathing aegis,

Minerva’s weapon when angered, with serpent-scales

and gold, and Medusa herself and her knotted snakes

on the goddess’s breast, neck severed and eyes lolling.