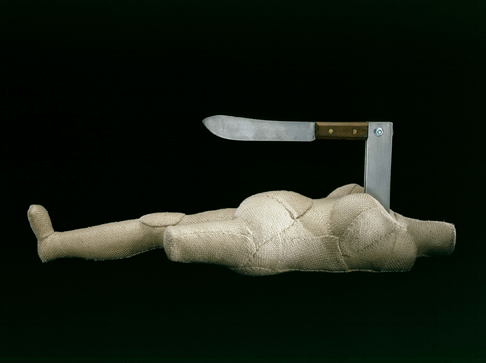

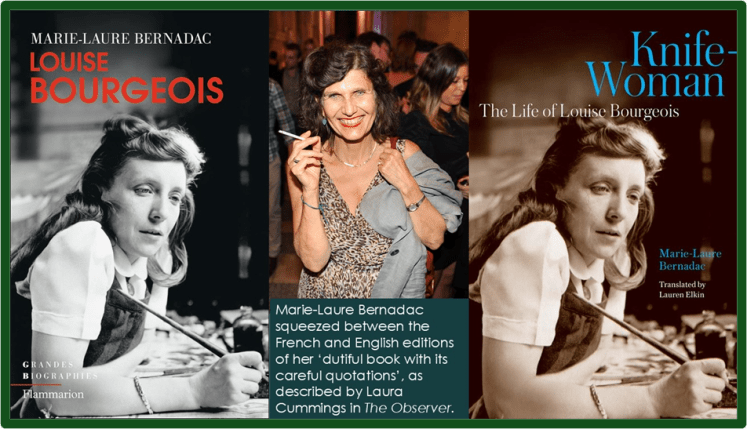

Yesterday I put online an admiring blog on the new (well!, newly translated to be accurate) biography of Louise Bourgeois (see it at this link) which in this translation is entitled Knife-Woman: The Life of Louise Bourgeois. There is no photograph of the artwork referenced by the title (‘Femme-Couteau’) which is meant to connote knfe woman and knife-wife so I wondered why last night I dreamed of it, frightening images crowding into a mental space that can’t contain them. The book however constantly goes over the basic fantasy projections of the image in Bourgeois’ conception of it, around images of the ‘cut’ or ‘cutting’, images of castration and its verbal equivalents in communication – the cutting comment – or in sociality – the cutting away of relationships considered but not ever truly natural – the family in short. The deeper connection to Bourgeois’ projection of this idea into her own mother (the icon of which is the cutting of the umbilical cord as an emblem of rejection) and herselfvariously projectively identified as bad mother, good mother, at her optimal, Winnicott’s ‘good-enough mother;‘. I thought of the many hints in Laura Cummings review that this biography was too ‘timid to see the real damage that Bourgeois did to her incarcerated brother,Pierre, cut by her to his fate in a none-too-wonderful mental asylum and to her adoptive and first son (adopted quickly because Louise thought her pregnancy would fail) only to give birth to her second son 6 months later. Cummings insists that the author of the biography OUGHT to have researched and written about how and why that son died so young. These are powerful motifs in the book – better written without the overt interpretation Cummings demands of Marie-Laure Bernadac.

Of the artwork itself, now I have recovered it again, one sees the double nature of the knife as it divides the woman who lies passively, perhaps dead or comatose passively beneath it, for it has already cut off the figure’s leg, both as an image of female castration that Bourgeois lay at her own mother’s door, and the danger of the ‘masculine’ icon, whether external or internal to herself, as something that diminishes woman whilst offering her an identity outside the womanly. The figure recalls an Egyptian Mummy too wrapped in grave-clothes but also sewn into them, demanding the knife that might undo the stitching.

It is an image that refuses to allow woman to be represented as a ‘victim’, as Bourgeois always did quite aggressively, but also acknowledges instances of such. It is a figure of ambivalent love and hate. But why did I dream of it. At the age of seven or so (the actual facts are hazy – only the image remains), I remember my mother brandishing a knife at me for some misdemeanor, whilst saying ‘Wait till your father gets home!’, an event I awaited with eager need – for he and loving as any man might be. My mother not so. She often voiced her view that she ‘hated’ children in front of me, was handy with beatings and scoldings – particularly in controlling eating at the table and clearing one’s plate. i remember my paternal grandmother objecting to her beating me for getting down from the Christmas table without eating all the food. Thereafter she cut every image of that grandmother from the photographs in the album. When I moved away from home, my maternal grandmother visiting myself and Geoff, my partner then (and still – some 45 years later) said to him: ‘I allis felt sorry for ar’ Steven’ (a Yorkshire sadness in the voice Geoff said). My mother was a hard woman, who adopted the knife almost unconsciously as her projection without the articulacy, but with the intelligence of bourgeois Bourgeois, for she was a Halifax mill-girl from the age of 14 when she left Siddal school (the factory down Boyes Lane between Salterhebble and Siddal, Halifax).

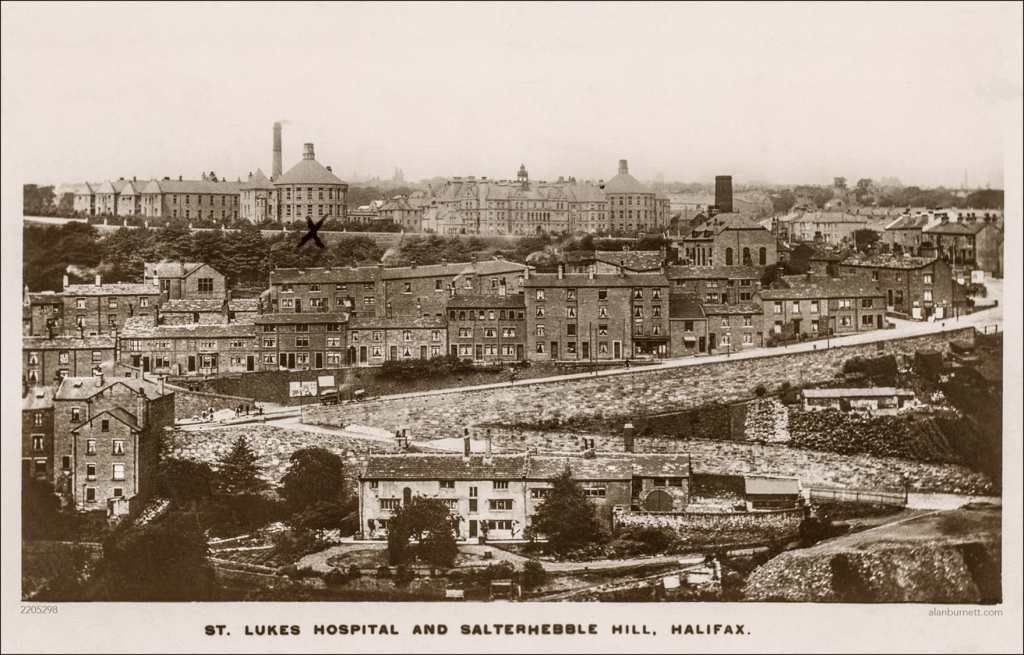

Looking down to the Hebble Valley at Salterhebble Hill, where my grandmother moved after leading Siddal – the hill on the other valley from which this is shot. The factory is off right down the hill to the valley bottom leading of the steep Salterhebble Hill. The canal was between the hospital (where my granddad fired the boilers and showed me round) and the rising hill.

There was no ‘subject position’, as they used to say, for my mother but the same knife that scared but empowered Bourgeois as Femme-Couteau, no place to be but there. I once attended a poetry writing school led by Andrew McMillan at Todmorden in the Hebble Valley and I tried to write about her in a not very good poem written there and then: the account of it at the blog on this link. Here’s the poem:

My mother donned her glasses And read a poem in that singsong Way; that taught to her in school Off Boyes Lane, Halifax, near the mill That worked out her bones. The voice she had now’s gone And its cracked resistance To the world, now shouts from Banners of the Right unfurled But they are wrong. Fear fosters Hate, but that was not she. A tight and strangled love Can sometimes in these latter days In red hope run brilliant, Vein oozing from a mineral stone.

The knife here has already cut and made the vein bleed idly in the harder parts of nature, but I think that is the rock of our total socio-political nature and we can become the resistance to the knife of hate and instead cut out the rotten that political hate is. I feel somewhat exorcised now.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxx