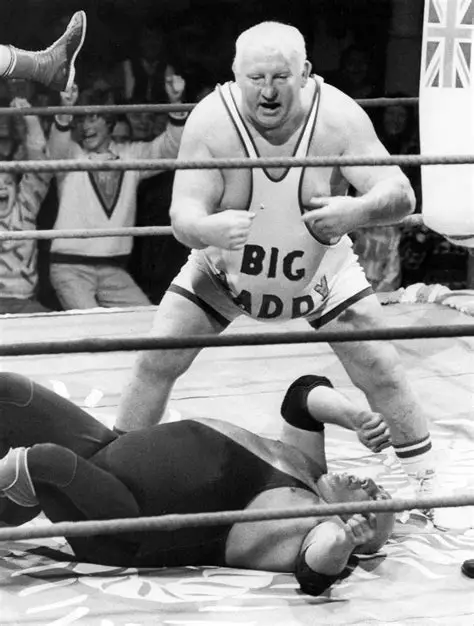

When I was but a child, the sport that filled those small flickering monochrome and then early colour TV screens was wrestling. It was killed off as a ‘sport’ when it was revealed that most of it was engineered for purposes of exciting spectators with over-exaggerated characters (‘Big Daddy’ and ‘Giant Haystacks’ for instance) with every move, including its supposedly competitive result fixed to maximise spectator pleasure in the charisma of both its heroes and villains. I remember the supposed horror of the popular press at the time in ‘exposing’ this corruption of a ‘sport’, particularly its prime feature for modern audiences – COMPETITION. The definition of sport that fuelled this furore, as it does the absurd version of the argument over the inclusion of trans sportspeople in gendered versions of sports, is the one used in Wikipedia, I suppose:. The disdain faced by wrestling players was that they failed in honouring the masculine virtues of honest competition and instead were as choreographed as ballet dancers (with a nod to the queer stereotype of that latter profession of what working-class culture at the time saw as half-me – the subject of Lee Hall’s Billy Elliot).

Sport is a physical activity or game, often competitive and organized, that maintains or improves physical ability and skills. Sport may provide enjoyment to participants and entertainment to spectators.[2] The number of participants in a particular sport can vary from hundreds of people to a single individual.

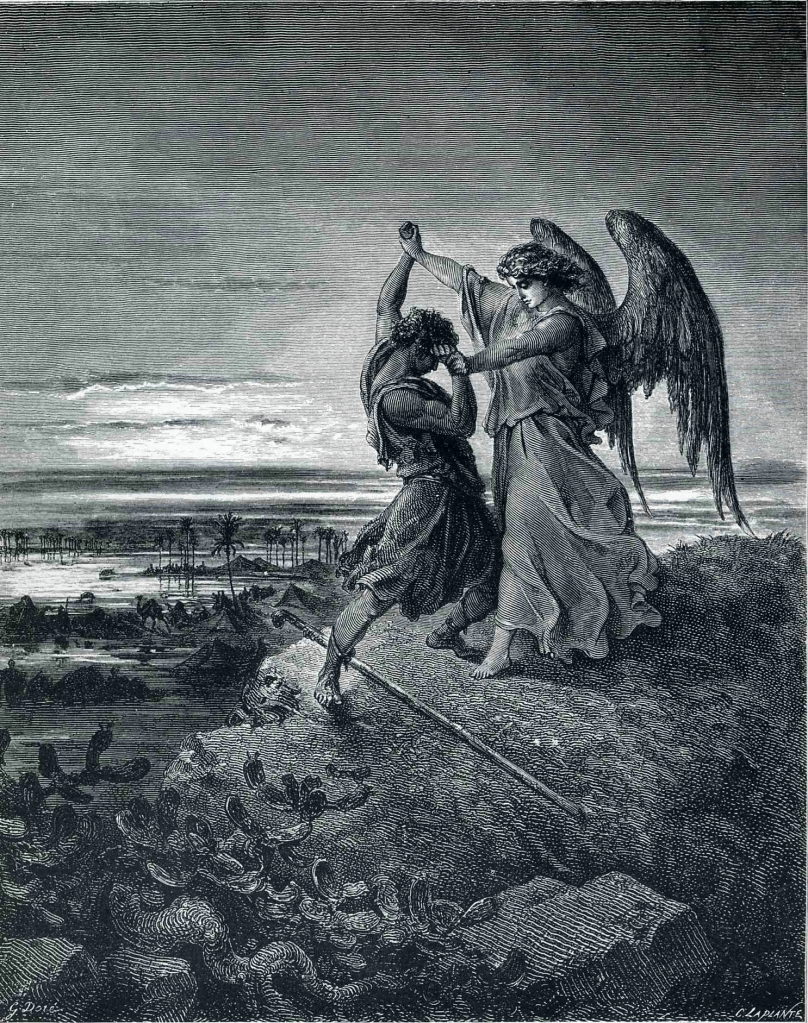

This ‘modern’ version had its origins in ancient Greek wrestling, still practiced in Byzantine gymnasia as in those of Ancient Greek Athens and Olympus, and in the Roman Empire which morphed into the Byzantine one. No wonder that fine Greek text the New Testament of the Bible honoured wrestling as a sport validated by God as well as by the earlier pagan Gods. Hence the beginning of the trope that was to flash through the history of art, the illustration of Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, a fight in which he established his role as the emblem of Israel, a nation and warlike people. Gustave Doré (1855) depicts that favourite artistic trope (in his Jacob Wrestling With an Angel. There is a little more on this, if excluding Doré) in my early blog on this trope at this link). Not that wrestling in which a semi-divine took place could ever be a fair contest of course, since angels – however hermaphroditic and transgender in their illustration (in Rembrandt particularly) – couldn’t be allowed to lose, though they need to allow little Israel to show his predictive masculine and militant might beyond mere bluster. Hence my choice of Doré here, for the angel just plays with Jacob, like an indulgent Mum-Dad with a recalcitrant self-obsessed boy. Doré makes it clear that this is spectator sport, as wrestling has become (but no longer on TV which had to believe in the competitive myth), by posing the battle on a cliff-edge surrounded by exotic cacti with and a desert oasis in the background (salvation perhaps).

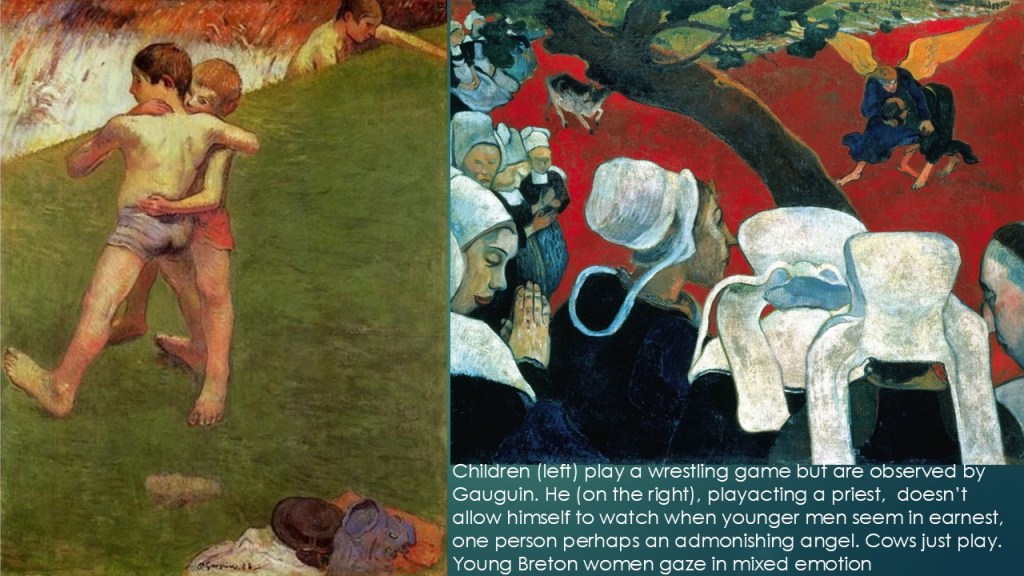

Though wrestling unbalanced by supernatural might is one thing. When Gauguin uses the trope, he queers it with humour. His famed self-portrait as the priest with his flock of Breton peasant women who have just heard a dry sermon, perhaps using the Jacob story, are outside the church treated to a vision of two lithe young men, though one has golden wings, wrestling on a background painted red with the passion of their struggle. The angel is, of course, winning, but the painting is less interested in the spectacle than in dramatising the gaze which makes this the spectator sport it is, in two different but associated ways. There is humour in this – not least in the spectating cow who with her four legs mimics the intersecting play of the two young me, or man and fair-haired angel. The young women who can be seen mimic their priest, showing that to look at such a thing as embodied might itself be a sin, bu we sense their side-glances, and indeed the bold gaze at these men by the women in the front row of the audience.

Wrestling is a close-body-contact sport, enacted in the nude in Greek gymnasia, and Gauguin plays with this in his picture of Boys playfully wrestling, with their clothes abandoned to the left of the picture. I have no doubt that Gauguin sports in the commingling of these boys’ bodies, even allowing it to confuse the origin of the four legs and feet between two young persons. The grasps of wrestling are necessarily physically ambiguous with embraces and with physical manifestations of human love, an important aspect of why God wrestles with Jacob, to show as it were his tough love, like that of a Big Daddy indeed. It is ‘tough love’ and you will remember God wounds Jacob’s thigh with his touch in order to remind him that God is grater – magically so – than men and their militant stereotypes.

If wrestling is now admittedly an all-show pleasant spectator pastime, it is worth remembering that the etymology of the word ‘sport in English, derived from Norman French of course, was originally not one that necessitated ideas of ‘competition’ nor overt organization and external control, as in the etymonline piece below shows:

sport (noun): early 15c., sporte, “pleasant pastime, activity that brings amusement; joking, foolery;” a shortening of disport “activity that offers amusement or relaxation; entertainment, fun” (c. 1300), also “a pastime or game; flirtation,” also pleasure taken in such activity (late 14c.); from Anglo-French disport, Old French desport, deport “pleasure, enjoyment, delight; solace, consolation; favor, privilege,” which is related to desporter, deporter “to divert, amuse, please, play” (see sport (v.)), also compare disport (n.).

Older sense are preserved in phrases such as in sport “in jest, by way of diversion” (mid-15c.). The meaning “game involving physical exercise” is recorded by 1520s. The sport of kings (1660s) originally was war-making. Other, lost senses of Middle English disport were “consolation, solace; a source of comfort.” In 16c.-17c. it could mean “sexual intercourse, love-making.”

The word is oft associated with the randy old Duke of Gloucester in Shakespeare’s King Lear, who uses it to label the fun illicit (saucy) sex can be for a young man with a young woman whom is not his wife:

GLOUCESTER But I have a son, sir, by order of law,

some year elder than this, who yet is no dearer in

my account. Though this knave came something

saucily to the world before he was sent for, yet was

his mother fair, there was good sport at his making,

and the whoreson must be acknowledged

(King Lear, Act 1, Scene 1, line 19ff.)

Good sport is not here a spectator sport except in the imagination of an old man thinking of his youthful prowess. As well as ‘pleasure though it denotes ‘pleasure’ taken in ways not validated by social propriety, something a bit shameful to admit thereof (in short, something considered by the English well into the nineteenth century and magnified by the Victorians, as typically ‘French’, and anti-social-order. Fencing is the sport of kings because it is a preparation for war and defence, and in this sense wears its competitive aspect, but note how Edmund, Gloucester’s ‘whoreson’ above mentioned, uses it to name not his noble defence of his father against his rebellious son, Edgar (a fiction he wants to maintain in his father’s face) but the version of it ‘played’ at by ‘drunkard’s in taverns. He decides his father will more likely believe his story if he draws some blood on his arm, as if Edgar had hurt him in wordfight:

Some blood drawn on me would beget opinion

Of my more fierce endeavor. I have seen drunkards

Do more than this in sport.

(King Lear, Act 2, Scene 1, line 36ff.)

Again sport in the mid sixteenth-century is used more of playful playing, not serious playing of a game, and a thing done in the moment, not organised, and with more than a hint of anti-social risk to self or others, of which we have no regard. This is the conclusion Shakespeare enforces of Gloucester’s ‘sport’ in siring Edmund as an unsought consequence of his sexual pleasure. By nearer the end of the play, Gloucester begins to align ‘sport’ with a cruel unthinking search for pleasure even when for others involved it means the most serious of consequences – poverty, exposure to the elements and death. In Act 4, he is told of Lear consorting on the heath with a madman, which reminds him of such another he has met – in fact both were the son Edgar misrepresented by Edmund. in being told this man was not just a beggar but a ‘madman’ too, he says:

He has some reason, else he could not beg.

I’ th’ last night’s storm, I such a fellow saw,

Which made me think a man a worm. My son

Came then into my mind, and yet my mind

Was then scarce friends with him. I have heard more since.

As flies to wanton boys are we to th’ gods;

They kill us for their sport.

(King Lear, Act 4, Scene 1, line 36ff.)

Personally I can’t help but giggle at the idea of ‘flies to wanton boys’ these days. But the boys in Lear are not those I am imagining:

What Gloucester is asserting is that: if the Gods like ‘sport’ they cannot be Gods who care for humankind. He compares them to boys who play a competitive game to see who can kill most of those common insects, flies. But I don’t think this reveals a mere point of etymology. What we call ‘organized’ and ‘competitive’ sport in modern times, is more defined by the goals of its profit-making organisation and competitive prize-winning, fuelling images of absurd wealth over the reality of a player’s sport that is for people not selected by its challenges, or able to maintain their appearance of celebrity otherwise. Think today of the Beckhams, whose whole purpose is the maintenance of image, and of the Super-League in Football with its obscene prizes at the cost of the game in its lower rankings. The real issue in selecting sport for play or watching has in the modern world increasingly been its collusion with the interests of a capitalist organisation of the social. i haven’t read but would like to, this book called Sport in Capitalist Society: A Short History by Tony Collins (2013), London, Routledge, DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203068113. Here is its abstract:

ABSTRACT:

- Why are the Olympic Games the driving force behind a clampdown on civil liberties?

- What makes sport an unwavering ally of nationalism and militarism?

- Is sport the new opiate of the masses?

These and many other questions are answered in this new radical history of sport by leading historian of sport and society, Professor Tony Collins.

Tracing the history of modern sport from its origins in the burgeoning capitalist economy of mid-eighteenth century England to the globalised corporate sport of today, the book argues that, far from the purity of sport being ‘corrupted’ by capitalism, modern sport is as much a product of capitalism as the factory, the stock exchange and the unemployment line.

Based on original sources, the book explains how sport has been shaped and moulded by the major political and economic events of the past two centuries, such as the French Revolution, the rise of modern nationalism and imperialism, the Russian Revolution, the Cold War and the imposition of the neo-liberal agenda in the last decades of the twentieth century. It highlights the symbiotic relationship between the media and sport, from the simultaneous emergence of print capitalism and modern sport in Georgian England to the rise of Murdoch’s global satellite television empire in the twenty-first century, and for the first time it explores the alternative, revolutionary models of sport in the early twentieth century.

Sport in a Capitalist Society is the first sustained attempt to explain the emergence of modern sport around the world as an integral part of the globalisation of capitalism. It is essential reading for anybody with an interest in the history or sociology of sport, or the social and cultural history of the modern world.

The choreography of modern sport is organised by the ideals of capitalism, riddled with its contradictions – asserting fair play but actually governed by advantages bought by capital in the interests of high returns (but the relality of huge obscenes wasteful losses too often), The Gods are still the ‘few’ and with regard to the ‘many’, should their needs cross those of the few,:’They kill us for their sport‘.

So nought but this skewed answer from me.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx