Source: https://observer.co.uk/culture/books/article/the-sunday-poem-burning-car-by-andrew-mcmillan

I suppose even physical clutter is the residue of memories, sometimes transmuted into obsessional and repetitive images – the better if repeated with a kind of nuance that varies each token from others in its type of memory. I use the words type and token as in philosophical metaphysics, explained in the link to a page in the last sentence. If you don’t want to read the whole entry, a sentence from that linked page’s introduction) might help to give a brief distinction: ‘The distinction between a type and its tokens is an ontological one between a general sort of thing and its particular concrete instances (to put it in an intuitive and preliminary way)’ [1] I clutter our house with a collection of tokens of the masculine, which recalls complex memories about memories of my struggles from the past – and perhaps still nascent. They are particularly with that type of memory that occasion definitions of masculinity to pass comparatively through moments of self-assessment.

Clutter can last a life-time but it may not – it may be a matter of brief periods before its clearance (or what seems as such on the surface) or substitution by further residue from a new token of the same type of memory. I wanted too write. I write about this because of a prompt from a new poem by Andrew McMillan, published in The Observer very recently. This poem is likely to find place in a new collection The Observer also tells us will be out soon. i can’t wait – Andrew is my favourite contemporary poet.It sparked interest in this WordPress prompt because it reminded me (if no one else, maybe not even Andrew McMillan for I am aware my readings are often only subjective) that memories fill your mind and not only in the case of major trauma: the thing I think McMillan refers to in these wonderful lines of painful predictive memories – of a cycle that might render boundaries of past, present and future somewhat irrelevant or compromised. It reminds of nothing more than clutter, although the clutter might rise to the level of an inner Diogenes Syndrome in the confusion of time boundaries in a ‘living room’, smaller than such needs demand, when we remember cyclical outbreaks of domestic disorder in a partner or lover who shares that confined space:

... the way your anger scorched

the place left its residue for days until

another thing blazed up .....

Be that about the clutter of traumatic or scarring memories or not, I find its instantiation as the residue of something set alight – some destructive blaze – powerful, full even of the taste of ash, charcoal and chemical discharge filling time and physical space with its stink and promise of more of the same.

Let’s look at the whole poem, which seems to me a poem about private space (perhaps ‘domestic space’ if that is the right word) but certainly one of joint ownership – the thing that unites the ‘living room and the car we own together together with its ‘closeness’ in every meaning of that word, including that prevalent in Yorkshire, where it is almost synonymous with the ‘mugginess’ evoked in parallel with it, but it is a word, ‘close’, that is full of resonance through other meanings that evoke privacy, secrecy, even imprisonment: ‘our own car close / and muggy‘.

we drive past at twenty-miles-an-hour to try

and get a closer look the seats melting

in the chassis' furnace the heat slipping

inside reddening our faces not shifting

for another junction our own car close

and muggy with the smoke so often

in the worst of it I longed for someone

to rubberneck past the living room

take in the scene the way your anger scorched

the place left its residue for days until

another thing blazed up would it have been different

with a witness? someone to take the keys

from my finger walk me away tell me

I was good that they could see that I was trying

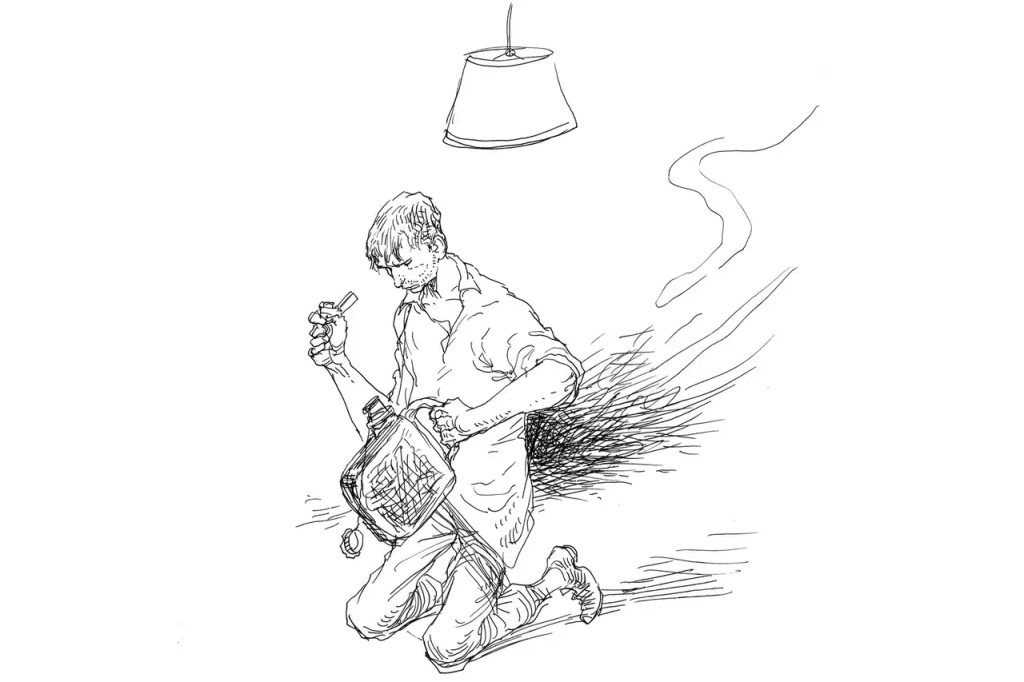

as they eased the can of petrol from my hand

It starts with the behaviour all of us notice where passengers in cars passing a road incident, a ‘car crash’ – for different kinds of ‘car crash’ become the poem’s subject, including those in some relationship, ‘rubberneck’ to catch a glimpse of a ‘tragedy’ in some other individual, family and couple’s lives. Wikipedia says:

Rubbernecking is a term primarily used to refer to bystanders stopping previous activity to stare at accidents. More generally, it can refer to anyone staring at an object of everyday interest compulsively. The term rubbernecking derives from the neck’s appearance while trying to get a better view, that is, craning one’s neck.

Rubberneck is associated with morbid curiosity. It is often the cause of traffic jams, sometimes referred to as “gapers’ block” or “gapers’ delay”, as drivers slow down to see what happened in a crash. Rubberneck is considered as of 2007 unconventional English or slang.[2]

The poem is about a ‘we’ with its conjoint (‘our’) spaces who get to ‘close’ to things that move from objects of a visual gaze or ‘look’ to ones that infiltrate and attempt to possess our own spaces – those we resist being seen and felt by others. Our feelings about others (outside our ‘private’ spaces in most respects) being capable of seeing inside that space are nuanced things. We resent being spied upon, though we too are capable of the behaviour, but at times long that another mind could validate the reasons why our private spaces sometimes feel unsafe and dangerous, an empathetic ‘witness’ to our situation, even though we keep the our awareness not only ‘private’ but secretly ‘close’ – like that atmosphere in a muggy room. The poem imagines the effect of a witness on these ‘close’ situations:

.... would it have been different

with a witness? someone to take the keys

from my finger walk me away tell me

I was good that they could see that I was trying

as they eased the can of petrol from my hand

The witness takes the ‘keys’ that indicate control, but perhaps they will see that we too may contribute to the ‘car crash’ or ‘blaze’ we are in our most ‘private space’ we blamed on our significant other only, for it us that have the petrol can fuelling the blazes we keep encountering (as in that wonderful illustration from The Observer above, accompanying this first publication of the poem). We always want to think that ‘I was good’, that our behaviour, even in private situations, could be evaluated positively, and that another would validate that fact. But maybe we also need people to see the roots of the possibility in us, and us alone, that we could be incendiaries in relation to our most personal relationships and loved significant others. This is a mature poem because it exposes the most vulnerable and even dangerous bits of our inner life. In this sense it is like the best of McMillan, the ‘Knotweed Poems series‘ for instance (see my blog on this) and their later appearance in Pandemonium (blogged on here).

McMillan longs for the witness to the privacy they own with selected others, and suggests that even the meltdown of of ‘our’ close and cosy spaces as well as being a fearsome inferno or ‘furnace also penetrates us so that our inner blazes reflect its fearsome ones, as if entered into our own ‘inside’ to make our faces ‘reddened’. There ao many reasons for red faces!.

... the seats melting

in the chassis' furnace the heat slipping

inside reddening our faces not shifting

for another junction

I was waiting for another McMillan poem, not in opposition to his late venture into novels (some of my thoughts are in this linked blog) but in promise of the continuation of a wonderful poet’s poetry.

All for now

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxx

___________________________________________________________