An man ready to play

It always amazes how often one can turn to Shakespeare’s Hamlet for assistance in interpreting a WordPress prompt question. Play is a word used as a verb and a related noun and is used so in this question, with the links well established between noun and verb for Hamlet too slips between them, even exploiting the etymological variance still present in the word- even that to being the name given to its originative meaning of “quick motion; recreation, exercise, any brisk activity”in Old English sweordplegan. Here is etymonline.com‘s summary of the etymology of the noun (the link to that of the verb being embedded within it – hence I won’t cite it).

play (n.): Middle English pleie, from Old English plega (West Saxon), plæga (Anglian) “quick motion; recreation, exercise, any brisk activity” (the latter sense preserved in swordplay — Old English sweordplegan — etc.), from or related to Old English plegan (see play (v.)). / By early Middle English it could mean variously, “a game, a martial sport, activity of children, joke or jesting, revelry, sexual indulgence.” The sporting sense of “the playing of a game” is attested from mid-15c.; that of “specific maneuver or attempt” is from 1868./ The meaning “dramatic performance” is attested by early 14c., perhaps late Old English.

In the play Hamlet, the word play as all the meanings of the noun on show and cited in its uses of language. Hamlet is a master of ‘playing’ – he writes and directs some travelling players in a ‘dramatic performance’ which deliberately mimics what his Father’s Ghost has told him to be the means of his death. He playacts when necessary by seeming to be that which he is not, or perhaps ‘is not’ (you are never sure with him how much his behaviour is purely performative). He plays or remembers play as a child with his father’s jester, Yorick, and he, of course engages in ‘sword play in Act 5 Scene 2 of the play that will turn out, as he knows to be more serious than a mere exercise of ‘playtime’.

Below (from line 209ff of Act V Scene 2.) is the prose introduction to the arrangement of the swordplay contest that he will engage in with Laertes, the son of Polonius whom Hamlet has killed, as Polonius hides behind a curtain in his mother’s bedroom, thinking him to be his Uncle, the murderous King Claudius. The lines could be set up as an answer to this question because they define Hamlet’s very contextually situated definition of when should be ‘playtime’ for him, as answers the King his Uncle-Stepfather’s question about whether his (Prince Hamlet’s) : ‘pleasure hold to play with Laertes, or that you will take longer time’. I love the circumlocutions about whether the indecisive Prince’s is still committed to his intention to play Now or soon after (at sweordplegan, as it were with Laertes) or whether he will take ‘longer time’ to fully commit. It is a circumlocution at the heart of this Shakepeare play – fo no-one knows if Hamlet will commit to anything and if he does, when precisely. This is the very reason his Father’s Ghost constantly insists that he ‘swear’ to avenge him, knowing (presumably) his son’s tendency to delay both a decisions to act and, having once apparently committed to an act, delaying its implementation.

LORD My lord, his Majesty commended him to you by

young Osric, who brings back to him that you

attend him in the hall. He sends to know if your

pleasure hold to play with Laertes, or that you will

take longer time.

HAMLET I am constant to my purposes. They follow

the King’s pleasure. If his fitness speaks, mine is

ready now or whensoever, provided I be so able as

now.

LORD The King and Queen and all are coming down.

HAMLET In happy time.

LORD The Queen desires you to use some gentle

entertainment to Laertes before you fall to play.

HAMLET She well instructs me. Lord exits.

HORATIO You will lose, my lord.

HAMLET I do not think so. Since he went into France, I

have been in continual practice. I shall win at the

odds; but thou wouldst not think how ill all’s here

about my heart. But it is no matter.

HORATIO Nay, good my lord—

HAMLET It is but foolery, but it is such a kind of

gaingiving as would perhaps trouble a woman.

HORATIO If your mind dislike anything, obey it. I will

forestall their repair hither and say you are not fit.

HAMLET Not a whit. We defy augury. There is a

special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be

now, ’tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be

now; if it be not now, yet it will come. The

readiness is all. Since no man of aught he leaves

knows, what is ’t to leave betimes? Let be.

Look at Hamlet’s answer. It is no more specific about when he might ‘play with Laertes’ than he might have been before, saying that he will ‘play’ at a ‘time’ that is decided by the King, which he pretends not to know even the King’s messenger says the time should be now. Moreover, even whether he will play when the King specifies it is pleasure it be then, will still depends upon a delaying factor: ‘provided I be so able’ as now’. What a circumlocutory – and hence delaying – way of saying ‘let’s play now, For I am ready’. So let’s ask Hamlet: ‘What says “playtime” to you, Prince Hamlet?’ No doubt his answer will still leave us guessing:

........ If it be

now, ’tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be

now; if it be not now, yet it will come.

If you were the irritable type, you might say, ‘Yes’, Prince Hamlet’ but I still don’t know if you intend to play in the present moment (‘now’) or at a time ‘to come’ in the future. Even if it is in the future, he will not specify when his ‘playtime’ might be precisely only that ‘it will come’ sometime in that future. After all Hamlet has just denied decisions can be made and implemented predictively, for he defies ‘augury‘, the kind that predicted from the behaviour of birds, such as ‘the fall of a sparrow’. Of course, all this is what we call ‘courtly wit’, in the manners and language of English Renaissance courts like those of the Tudors and Stuarts and is a kind of ‘play’ with words and ideas that refuses to be serious.

And the one thing we think we know about ‘play’ is that it thought to be the antonym of a ‘serious’ action. However, look too throughout this ‘play’how ‘play, with any or all meanings, is constantly refused a definition that makes it the antonym of serious action, whether in a formal dramatic performance’, such as The Murder of Gonzago or The Mousetrap (two titles of the same play within this play spoken of in Hamlet Act 2 Scene 2, 561ff. and Act 3, scene 2 261ff. respectively), or roleplay of a character by another character (Hamlet as a madman) or a sword game match. Hamlet is full of playful jokes on sexual matters too that cross every boundaries even of sex / gender, and applied as easily to Hamlet’s male as well as female friends (Rosencrantz and Guildenstern as well as Ophelia) and the invitation to ‘play with Laertes’ is taken in this way too by the Prince comparing his prevarication at committing to ‘play with Laertes’ to that of a ‘woman’ holding back her favours. Even the Queen plays unknowingly with such opportunities in the double meanings of her request to Hamlet that he ‘use some gentle / entertainment to Laertes before you fall to play’, almost a definition of foreplay. Entertainment is another word undergoing change from a serious function of courtly respect to another, an inferior in particular, to being a word related to playing.

entertainment (n.) 1530s, “provision for support of a retainer; manner of social behavior,” now obsolete, along with other 16c. senses; from entertain + -ment. Meaning “the amusement of someone” is from 1610s; sense of “that which entertains” is from 1650s; that of “public performance or display meant to amuse” is from 1727.

That is the Queen asks Hamlet to use Laertes with ‘gentle’ ways (the ways becoming a gentleman noble but a secondary sense of asking him to ‘amuse; Laertes brings out the other meanings of ‘play’ other than the sportive one. But if all this is playful it is already deadly serious, as Hamlet knows that armed with a sword, he has that capability of going for the serious action of killing Claudius at close quarters. What he does not know, of course, is that Claudius has already poisoned the tip of Laertes fencing sword so that its scratch alone will be deadly to Hamlet: in which case ‘the fall of a sparrow’ might augur the death of a Prince rather than whether he wins or loses a playful game. It seems that playing and playtime can have more of serious action in it than we know.

In fact that seems to be the problem for Hamlet the Prince. No playful thing can be such for him for every act bears any number of consequences that he fears, as his famed ‘To be or not to be’ speech underlines. For no-one knows properly of him ‘how ill all’s here / about my heart’. And art is the place par excellence of showing that something apparent light and inconsequential like ‘playing’ can be deadly serious. Oscar Wilde was so sure of that he played centrally with The Importance of Being Earnest, wherein young men become so afraid of being serious (earnest in the Victorian sense of morally serious and committed to what you say) that they have to rename ‘playtime’ by a name that suggests they are engaged in a serious purpose at the time – caring for an invalid named Bunbury. Thus Bunburying was born as a kind of playtime no-one need worry about when you set yourself such a time to play, as played with the dialogue between Algernon, and Jack (playacting as Earnest / earnest – in two senses) below, where the most serious ability of a young queer man is to play as if they were doing something society thinks laudable:

The most serious words in the world are: ‘The readiness is all’. Hamlet is a play that insists that if you continue to live you must be ‘ready’ at all times for all eventualities, serious or playful, even the death you evade when you contemplate suicide without doing it. It is a very dark play indeed.

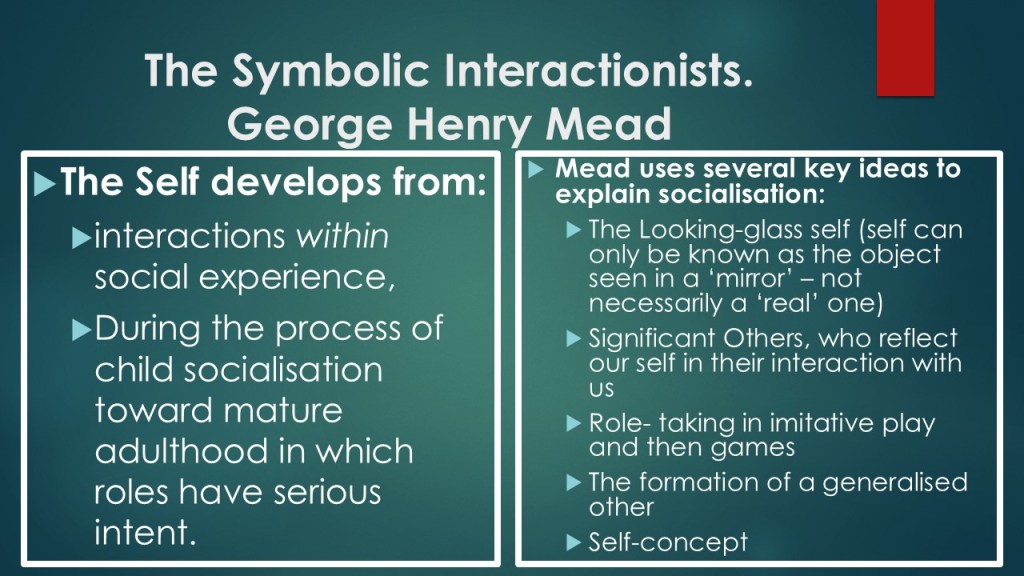

After all, the Symbolic Interactionist psycho-sociological philosophers confound even infant play with a serious purpose – working toward from a starting point play stage to an an understanding of the game of everyday life. Now ask me again: ‘Do you play in your daily life?’ I never do anything less serious than play for all my life is worth.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxx